China's Campaign to Defend Itself Against U.S. Germ War Attack

A May 1952 poster, designed by the PRC's Propaganda Department of the Central Ministry of Health & the All-China Artists Association, illustrates efforts undertaken to respond to US bioweapons attack

This essay will take an in-depth look at a notable Chinese poster from the Korean War that aimed at mobilizing the population against the dangers of a biological weapons (BW) attack by the forces of United Nations Command, led by the United States.

For the purposes of this article, to provide a context for understanding this particular evidence about the U.S. germ war campaign we will look at a well-received academic work examining China’s large-scale public health campaign during the Korean War. A few other examples of Chinese poster art, issued to mobilize the population against germ war attack, are included here for educative purposes.

Science and Politics in Academia

In May 2002, Professor Ruth Rogaski published an essay in The Journal of Asian Studies, “Nature, Annihilation, and Modernity: China's Korean War Germ-Warfare Experience Reconsidered.” Rogaski’s research ironically showed the opposite of what her thesis claimed.

Rogaski, then an assistant history professor at Princeton University, believed that Chinese scientists were coerced to participate in the Patriotic Hygiene Campaign that followed discovery of germ war attacks in the early winter months of 1952. She took as good coin that there was evidence of a germ warfare “hoax” conducted by Communist officials, as described in a dozen alleged documents supposedly found years later in a Soviet archive after the fall of the USSR.

I recently released a long academic paper debunking those alleged documents and the claim of a biological warfare hoax more generally. In that paper, as well as elsewhere, I have shown that it is highly unlikely that academicians and journalists who reference the supposed Soviet archive documents, which were first described by Cold War professors Kathryn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg, had closely examined the materials themselves. I can say this because the “Soviet” documents betray their falseness via contradictory timelines, non-factual statements, etc. Not one of the historians or journalists who reference the Weathsby/Leitenberg documents ever mention any of these issues (Rogaski included). They simply accept them, a classic example of argumentum ab auctoritate.

“For fleas, flies, mosquitos, crickets, spiders, sandflies, and other poisonous insects dropped by enemy planes, you must use DDT solution or soapy water with kerosene to kill them”

In her essay, Rogaski expressed surprise when she found that public health officials had not been coerced to countenance supposed lies about a supposed U.S. germ war attack that (supposedly) never occurred. There was in fact no evidence of any such coercion at all! Instead, Rogaski found that public health officials in the city she closely examined, Tianjin, had reacted honestly and with candor when faced with popular reports that infected insects had appeared in their city as part of an American biological warfare campaign.

The officials concluded “that it was impossible to prove that the insects that were discovered in Tianjin in the summer of 1952 were in fact manifestations of biological weapons at all.... Public health officials pointed to environmental factors that may have accounted for unusual massings of insects, including humid winds and decreasing barometric pressure” (Rogaski, pg. 385).

That doesn’t sound like Chinese public health officials had been suborned into backing a propaganda “hoax” about U.S. biological weapons attack. But it bothered Professor Rogaski that despite a supposed dearth of evidence of BW attack, Tianjin health officials had not let “scientific doubt… deter political response,” and “immediately organized mass defensive action against the bugs” (Ibid.).

It’s likely, however, that Tianjin health officials, uncertain about what was happening, decided better to be safe than sorry, and ordered a mass round-up and destruction of insects and vermin in the vicinity. When these kinds of round-ups metamorphosed into a nationwide public health campaign, local officials also participated. For Rogaski, this was described as an immersion into some kind of “annihilation” ideology that transcended the public health sphere and emanated from Maoist political doctrine as a whole.

As she describes it, Chinese scientists were under great political pressure to press the germ war charges. Meanwhile Western scientists, including famed UK scientist Joseph Needham and the International Scientific Commission (ISC) who travelled to China and the DPRK to examine the charges, were dupes who did no scientific investigation but simply believed what Chinese scientists told them.

The idea that Needham and his associates in China never approached the BW evidence scientifically is belied by an examination of their full report, with all appendices, something that was near impossible to view for most interested parties until I published a full digital copy of the report in February 2018.

An example of the ISC’s scientific approach appears as early as pg. 13 of the ISC report, as pictured below. In addition, original scientific investigations were undertaken by China’s Academia Sinica under supervision of the ISC, or via direct ISC intervention, as can be seen in Appendices E, F, Ja, Jb, N, etc. of the ISC report.

It has not escaped my attention that the emphasis of Western critics on the supposed lack of Western scientific examination of direct U.S. BW attack has the effect of minimizing, if not erasing, the impressive scientific work done by North Korean and Chinese entomologists, lab technicians, bacteriologists, etc. in documenting the BW attacks. The diminution of the work of these doctors and scientists carries with it a stench of imperialist hauteur, which has surrounded Western denials of the U.S. germ warfare evidence from the very beginning.

“The fear of germ-warfare attacks was palpably real”

Rogaski’s entire essay, as interesting as it is with its references to the documentation of the public health response to the germ war attacks, is hobbled by vague academic theories. This is because the good professor has no where else really to go, since she has eschewed any allowance that the biowar accusations could be true. Hence, for instance, she maintains a belief that the “annihilation” of insects was a stand in for the political conflicts faced by China in the early days after the victory of the Revolution.

Still, it’s strange that Rogaski ignored the fact that the records showed — records she quoted! — that the insects found in Tianjin had proven in the lab to harbor “typhoid bacilli, dysentery bacilli, and paratyphoid,” according to local city records. That doesn’t mean those insects were deliberately infected and dropped by U.S. planes, but these were findings that could not be ignored by health authorities.

Nor, though Professor Rogaski mentions it later in her article, did her hypothesis that Chinese officials had been coerced into backing the government’s hygiene campaign take fully into account the fact that China had been under bacteriological weapons attack by Japan within the past decade. Many thousands had died. Historian Sheldon Harris, who wrote one of the most famous books on Imperial Japan’s biological warfare program, said over 200,000 were killed in China from from biological weapons attack. The fact that the U.S. had hidden these facts from the world for decades, which Harris documented, along with journalist John W. Powell before him, influences how we assess U.S. denials about the 1951-53 germ war campaign.

The BW deaths in China during the 1940s were themselves swamped by the larger tragedy that saw 20 million Chinese killed by Japanese forces in the Second Sino-Japanese War. The countryside had been devastated. Public health measures in the late 1940s and early 1950s and beyond directly addressed the dire state of China after Japan’s defeat and the ostensible end of the Civil War with the Kuomintang. At no time did Communist officials in China or Korea ever deny that their countries had serious public health challenges unrelated to the U.S. germ war attacks.

Even so by the time of the Korean War, “The fear of germ-warfare attacks was palpably real” in China, Rogaski wrote (p. 388). Yet she continued in her essay to emphasize the supposed baleful influence of Maoist political influence in the germ war accounts over any actual response to danger. Chinese scientists and medical officials were seen as succumbing to a false propaganda campaign about U.S. BW attack.

While the Patriotic Hygiene Campaign had the benefit of also mobilizing against major health problems faced by the new regime, Rogaski could not bring herself to even speculate that the germ war attacks could be real. This adherence to U.S. ideological denials and cover-stories about the germ war attacks is typical of U.S. journalists and historians.

In 2020, I wrote to Professor Rogaski, thinking she would be interested in my discovery of two dozen CIA communications intelligence (COMINT) records that cited both Chinese and North Korean military units conversing about the problems occasioned by being under BW attack. Like so many academics to whom I have written on this issue, she never bothered to respond to me. No U.S. academician has mentioned the CIA COMINT reports to this day, nearly 15 years since their public release!

The reason to single out the Rogaski essay is that 1) it is often quoted and considered a landmark study linking China’s huge public health campaigns from the early 1950s with propaganda that originated in the charges of U.S. germ war attack; and 2) the essay demonstrates the bias and arrogance (and I suspect, fear) of U.S. academics when they approach the subject of U.S. BW activities in the Korean War.

As we shall see in our analysis of a 1952 Chinese effort to address the biological warfare danger, the public health measures were triggered not merely by the appearance of insects or vermin, but by observations of U.S. planes “dropping poisonous insects or other substances” (see Panel B (2) below). This important aspect of China’s public health campaign against the danger of U.S. biological weapons attack cannot be emphasized too much.

“Everyone come participate”

I want to spend the bulk of this essay examining the extraordinary poster directly above, which the Chinese government released in May 1952, some five months after the large-scale aerial U.S. BW campaign began in northern DPRK and northeastern Manchuria. Titled “How to defend against American imperialist bacteriological warfare,” the poster was designed by the Propaganda Department of the Central Ministry of Health, in conjunction with the All-China Artists Association. The poster was originally published by the People’s Fine Arts Publishing in Beijing.

I found the poster at the University of Cambridge’s Digital Library, which asks visitors to “please share this page on social media.” I don’t know if anyone else has done so, but I’m certainly following that request. The original for this digital poster resides at The Needham Research Institute in Cambridge, England.

There is a great deal to learn here about how the Chinese government saw the germ warfare campaign as it unfolded, and what they felt was essential to communicate to the population in order to blunt the effect of the germs and viruses dropped on the population in order to either kill or incapacitate, and in any case to terrorize, both military and civilians alike.

On each side of the poster is a slogan written in large Chinese characters. The slogan on the left says, in translation, “Completely defeat the American imperialists’ germ warfare!” On the right it says, “Everyone come participate in the patriotic epidemic prevention and hygiene movement.” (Translations are from the University of Cambridge website, and likely are the work, as stated in its metadata section, of Sally Church, Sally Yan, Mary Brazelton, and Henry Jones.)

Let’s look at the panels one by one. All the quoted material below is from the University of Cambridge webpage for this poster.

Panel A (1), in the top left of the poster, says:

American imperialists are spreading insects and other poisonous creatures containing bacteria and viruses in North Korea and the northeast and other regions of our country to in [sic] efforts to create plagues and kill peaceful residents. We must organize ourselves to learn knowledge about epidemic prevention and prevent American imperialists’ germ warfare.

The poster within the panel, which the man on the right is pointing to, is labeled in Chinese, “Epidemic Prevention and Hygiene Poster.”

Panel B (2), in the top right of the poster, says:

When you discover that enemy planes [are] dropping poisonous insects or other substances, you must immediately report this to the hygiene and epidemic prevention office.

Notice that the witnessing of enemy planes dropping insects is an important part of the identification of germ warfare attack. Hundreds of witnesses of these biological weapons drops exist, many dozens by name in the April 1952 report of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers, who visited both North Korean and China. Witnesses are also named in the September 1952 report of Joseph Needham’s International Scientific Commission, and other sundry documents.

Even Ruth Rogaski’s 2002 essay discussed above states, “Those who most ardently defend the [BW] allegations today are members of the medical and public health professions, many of whom profess to have personally witnessed the aftermath of American germ-warfare attacks in Manchuria and North Korea” (pg. 409, italics added for emphasis).

Panel C (3), middle row of panels on far left, reads:

Before going to exterminate the poisonous insects, everyone should fasten their cuffs and legs of their trousers, put on socks and shoes, put on a mask, wrap their heads with cloth, and put on gloves. You must be careful to protect yourself and not give germs a chance to invade your body.

Panel D (4), middle row, second from left, reads:

For rats, frogs, etc. dropped by enemy planes, you must use steel shovels to kill them and burn them or bury them in deep pits.

The emphasis here is on destroying vermin or small animals dropped by enemy planes, and not simply rounding up vermin, etc. and killing them. Such more broadly aimed activities apparently did take place, if Rogaski’s research in any indication.

Panel E (5), middle row, second from the right, reads:

For fleas, flies, mosquitos, crickets, spiders, sandflies, and other poisonous insects dropped by enemy planes, you must use DDT solution or soapy water with kerosene to kill them; you can also use swatters, nets, torches, and boiling water to catch and kill them. Collect them and burn them or dig deep pits to bury them.

Again, the emphasis is on infected creatures, in this case insects, dropped from planes.

Panel F (6), middle row, far right, states:

For rags, leaves, feathers, daily-use products, food products, and other poisonous things dropped by enemy planes, as well as brooms used to fight poisonous insects, you must burn these together with hay and bury the remaining ashes in deep pits.

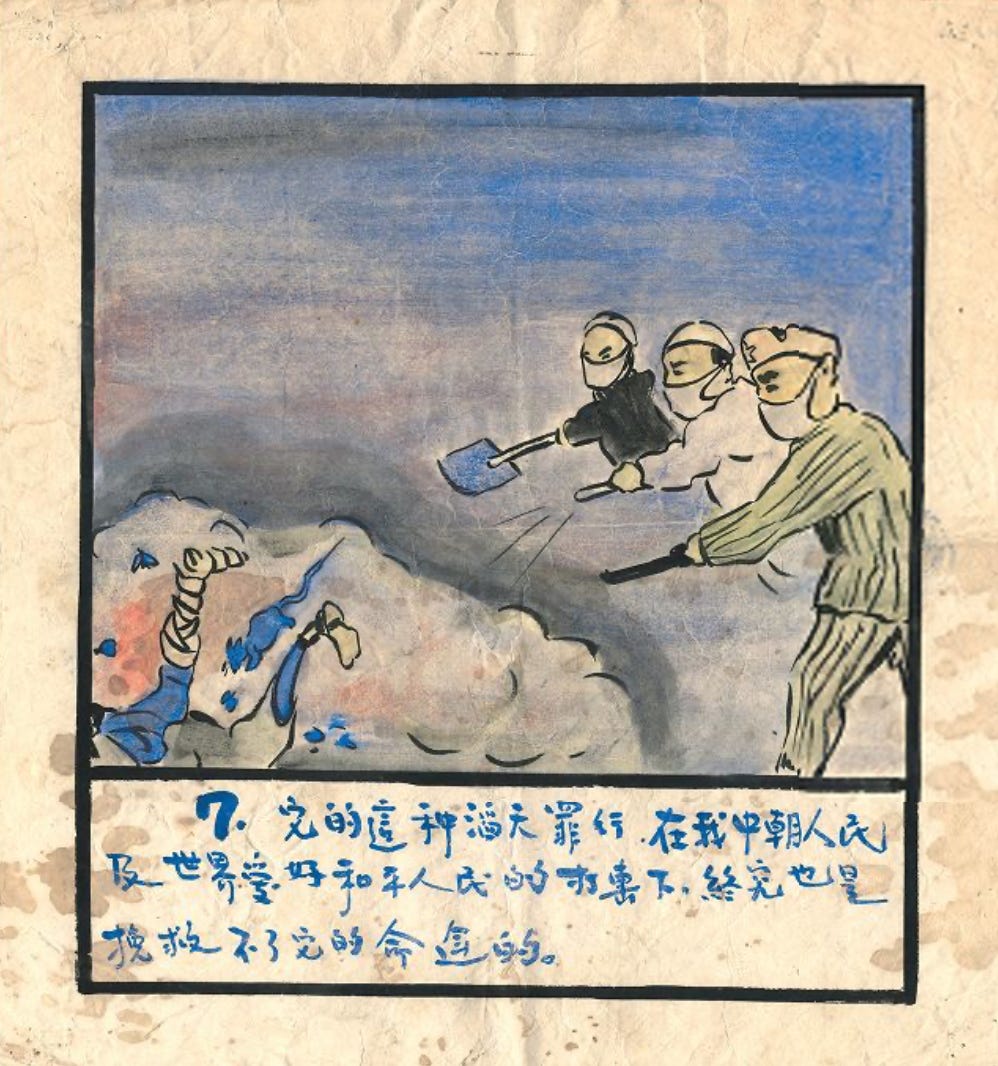

Panel G (7), bottom row, far left, reads:

After the work is done, clothes, shoes and socks, globes [?], cloths to cover the head, masks, etc. must be washed with boiling water. Every person must take a bath and change clothes. Tools for killing poisonous insects and poisonous things must be soaked in lime water or bleached water.

Note: the container, either a box or a pail, to the right, says “Lime water.”

Panel H (8), bottom row, second from the left, says:

For areas that have been sprayed with poisonous insects by enemy planes, immediately mark with signs, seal them off, and cut off any traffic. Do not let anyone pass through, so as to not spread epidemic disease.

Note: The sign on the tree reads, “Passage prohibited in poisoning area.” The sign on the rope or chain, acting as a gate across the road, reads “Passage prohibited.”

Panel I (9), bottom row, second from the right, reads:

If you discover a patient, you must call a doctor immediately. If it is an infectious disease, immediately report it to the hygiene and epidemic prevention office.

Note: The poster in the rear of the panel translates as “Preventative Inoculation,” or what we would call vaccination.

Panel J (10), the final panel in the lower right-hand corner, reads:

People suffering from infectious diseases should be immediately sent to isolation centers, infectious disease hospitals, or places designated by epidemic prevention offices in order to undergo isolation and treatment, so as to not infect other people.

Note: The sign on the building to the far right identifies the building as the “Zhangjia Village Infectious Disease Isolation Center.” There is more than one Zhangjia village in China, and it’s unknown if the sign in the poster here refers to a specific village or if it’s merely meant to convey an example.

Conclusion

In summary, it appears that Chinese health officials, many of whom were educated in the West, had an excellent handle on necessary public health measures in the wake of germ war attack. This may be why the U.S. BW attacks were so apparently unsuccessful. I say “apparently,” because the assessment of the casualties from these attacks are still kept secret by both Communist (PRC, DPRK) authorities, and their U.S. wartime opponents.

Rogaski and others could have written essays about what Chinese doctors had learned from their encounter with Japanese biological warfare attack, and how that was utilized in constructing a public health response to renewed bacteriological attacks, this time from a former erstwhile ally, the United States.

But in the obsessed anti-communist milieu of American academia, such reasonable forays into the real history of public health are forgone in order to make political accusations against Communist doctors and scientists dissimulating the basis for a public health emergency. This is all the more obscene when it is one’s own government that launched the biowar attacks that in many ways necessitated the public health campaign to begin with. U.S. scholars should be far more sensitive to the record of U.S. atrocities in wartime.

Cuba faced similar attacks, though the most notable were economic attacks with insects and pathogens against their agriculture which destroyed most of their poultry and swine farming along with severely limiting tobacco and sugar exports for foreign exchange. The several attempts at inflicting human casualties with pathogens such as hemorrhagic fever viruses were less successful but still effective enough to be noted- One of the reasons Cuba has felt the need to train a LOT more medical people than other economies in their climactic zone/of their size.

https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/19626-national-security-archive-doc-15-nsc-memorandum

http://www.cubanews.acn.cu/cuba/21493-germ-warfare-a-long-standing-war-against-cuba