CIA, MKULTRA and the Cover-up of U.S. Germ Warfare in the Korean War

Behind the "brainwashing" scare of the 1950s was a scandal that concerned U.S. use of biological weapons and CIA experiments in torture and mind control on POWs returning from the Korean War

In this fully documented article, CIA mind-control programs are linked to experiments on returning Korean War POWs, including experiments on inducing amnesia and implanting false memories. Also revealed is the extent to which CIA officials from Projects Bluebird, Artichoke and MKULTRA collaborated with U.S. biological warfare (BW) efforts, including the top secret “processing” of high-ranking POWs who confessed to U.S. use of biological weapons in Korea. Included in this article are brief biographical sketches of key figures.

This is a long involved story, and until this article was originally published at Counterpunch (Nov. 21, 2021), many of the events described herein had never been told. This article has long been under a pay-wall, but is published here entirely free for the first time. This most current version has been edited to include new information bearing upon the issue of the POW BW confessions.

Introduction

It was the propaganda version of an incendiary bomb. In Spring 1952, U.S. Air Force and Marine flyers, shot down during the Korean War, testified publicly that they had been ordered to drop biological weapons (BW) on China and North Korea. This was followed by written depositions that detailed each flyer’s knowledge about the germ war: who ordered it, where the weapons came from, the training involved, and the secrecy that surrounded the entire operation.

The confessions of the U.S. flyers (video 10:00-12:30 min), along with an arguably unprecedented degree of compliance and collaboration among U.S. prisoners of war in general, was cause for alarm among Pentagon brass and CIA officials. It would lead to a number of court-martials over the years following the Korean War, though — with the equivocal exception of Colonel Frank Schwable, who though ultimately cleared, was subjected to a Marine Corps Court of Inquiry — none of the BW POW confessors were court-martialed.

The flyers may not have faced trial, but their confessions had to obliterated from the public’s mind. So the confessions were suppressed, written off as the product of unimaginable torture and diabolical and novel brainwashing techniques. Public retractions of the confessions were arranged. Copies of the confessions were suppressed. At the same time, a covert U.S. psychological warfare campaign was undertaken to challenge the flyers’ statements. Months before any confessions were actually made, military and CIA-linked social scientists, psychologists and psychiatrists were advocating preparation for a spate of confessions.

The apparent belief in widespread collaboration by U.S. prisoners with their Chinese and North Korean captors led to the proposal to use controversial mind control (“brainwashing”) techniques in their debriefing, once they were returned into U.S. custody. These techniques were the product of top secret research programs run by the CIA and various military components, which during that period came under different names: Project Bluebird, QKHILLTOP, Project Artichoke, and by spring 1953, MKULTRA.

Behind the fears of supposed brainwashing and/or torture of POWs to obtain false confessions about use of biological weapons was a cynical and suppressed fact: the Pentagon had briefed the Air Force and Marine officers flying the BW missions that they could provide whatever operational information they deemed necessary to their captors. The rationale was to avoid possible torture. But the fact the flyers were given such instructions was suppressed from the public record.

The fact we even know about this was due to extraordinary publicity surrounding a 1954 Marine Corps inquiry into the actions of Colonel Frank Schwable, a top-ranking official captured by the Communists, who had provided his interrogators with detailed information about the genesis and evolution of the U.S. biological warfare campaign. The full story of Schwable’s Marine Corps inquiry, and the revelations that briefly surfaced in the U.S. press about the instructions to “tell all” if captured, is too long to relate in full here, and readers are directed to this article, which describes this episode in much greater detail.

As some POWs first began to be released in March 1953, the CIA organized an experiment in interrogation of approximately two dozen returning prisoners at a U.S. Army hospital that included use of experimental drugs, “speedballs”, and hypnosis, an experiment that was cancelled at only the last minute, after security for the operation was blown, and the Surgeon General demurred over the use of the experimental drug. Documents show, however, that the experiment was secretly implemented weeks or months later.

The Air Force and Marine flyers who confessed to dropping bacteria-laden bombs, using insect vectors similar to those used by the Japanese in World War II, and also spray devices to spread biological agents, were told they were under investigation, and possibly faced charges. In the case of Col. Schwable, his retraction was screened and heavily edited, and even typed, by agents of the Army’s highly secret Counter Intelligence Corps. The ex-POWs who had confessed to BW were also manipulated into putting one of their own forward as a spokesperson for them, choosing the one flyer with top CIA connections.

This article will review the existing evidence of intelligence agencies’ manipulation of the flyers’ testimony about the use of BW in the Korean War, as well as the direct connection between not only the suppression of the flyers’ testimony and CIA mind control programs, but between those various programs and the U.S. biological warfare program itself.

Thanks to various researchers and documentarians, readers might be aware of the links between the CIA and the biological warfare campaign via the Special Operations Division at Fort Detrick. But the connections will turn out to be much broader than that, going all the way back to the struggle inside government to expand the biological warfare program in the late 1940s.

The story is a dark one, touching upon the culpability of a generation of scientists, doctors and academicians from some of America’s most hallowed institutions. It is a tale of massive social corruption and decay, and its final chapter is not yet written.

“Brainwashing” and the Return of the POWs

The CIA’s interest in the returning POWs was not limited to the confessing flyers. There had been a good deal of what the military saw as POW “collaboration” with the enemy — signing peace petitions, making public antiwar statements, etc. There also was paranoia about whether any of the returning prisoners had been “turned” into double agents.

As it was, twenty-two former POWs declined repatriation back to the United States at the end of the war, deciding (at least for a time) to stay in North Korea or China. One of these former Communist prisoners warned his mother, “They have probably told you that I was forced, duped, brain-washed, or some other horse manure that they use to slander and defile people like myself who will stand up for his own rights and the rights of man.”

Fearful of Communist subversion, counterintelligence officialdom in the U.S. military and CIA were roused into action.

In 1952 and 1953, at the time of the heaviest BW accusations from the Soviet Union, China and North Korea, and influenced by reports from international investigators, Chinese missionaries and high-Anglican and Catholic church officials, and Communist press, many people around the world were sympathetic to China and North Korea’s charges of germ warfare. On May 11, 1952, an estimated 8,000-11,000 people came to Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens to hear the Reverend Dr. Endicott talk about his visit to North Korea and his findings on the use of bacteriological weapons by the United States.

Recently, the decades-old charges of U.S. biological warfare during the Korean War were revivified by the discovery of dozens of former top secret communications intelligence reports, declassified by the CIA, that documented the reactions of China and North Korea’s military units to attack by BW weapons. Despite total silence by historians in regards to these documents – neither attacking nor defending them – the fact of U.S. use of germ warfare during the Korean War seems to have passed the Rubicon of plausible truth.

But back in the pre-Internet world of 1951, faced with an alternate view of the Korean War from Soviet, Chinese, North Korean and other communist and leftist sources, the U.S. government implemented a huge program of censorship of the mails, with the aim of stopping any news from the Communist world from entering the United States. Over the years, millions of pieces of mail, journals, books, pamphlets and other material was seized by U.S. Customs and the U.S. Postal Service and destroyed. This heavy-handed censorship ultimately sparked protest from the U.S. scientific community, but it wasn’t stopped until the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in 1965.

By spring 1953, with the war winding down and an exchange of prisoners imminent, the question about how to deal with the collaborating POWs, including those who confessed to BW, was tossed about in military and intelligence circles. But unknown to most, steps were being taken to deal with U.S. Air Force prisoners making “false confessions” to their captors as early as 1951 by CIA-connected social scientists, psychologists and psychiatrists, even before any flyers’ confessions had been made, as further described below.

By autumn 1953, the Air Force had established a policy board at Air Staff level to deal with suspected POW collaboration with the Communists. Once the POW release was imminent, government officials worried about the security risk these prisoners presented. Meanwhile, the U.S. press, spurred on by the CIA, had raised the specter of “brainwashing,” while claiming U.S. flyers had been tortured into confessing to germ warfare, and undertaking other cooperative behaviors.

Thus began a top secret Air Force research study of the returning POWs, under the auspices of the Air Research and Development Command (ARDC), the same department of the Air Force involved in constructing new biological weaponry. Codenamed Project Repair, it consisted of interdisciplinary teams of psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, anthropologists, and statisticians working for the Air Force’s new Human Resources Research Institute (HRRI). Data included “a vast body of written material obtained by agencies other than the project staff (such as intelligence interviews), [and] psychiatric interviews with a number of the prisoners.”

The Air Force had its own agenda: dealing with public opinion on the POWs; medical rehabilitation of the prisoners; security issues (with the concern that some of the prisoners had been flipped to support the Communist side); and the problem of punishment (what prisoners should be punished for collaboration or revealing secrets, and what should that punishment be).

The CIA’s own interests were partly congruent, but the Agency had already embarked on a wide-ranging behavioral research program that embraced everything from the efficacy of lie detectors to the use of LSD, drugs, electric shock and other forms of psychological and physical pressures in interrogation.

On April 13, 1953 the CIA’s MKULTRA program was established. Its underlying purpose was to perfect the control of the human mind, and the consequent manipulation of human behavior. The impetus for the program was fear of communist influence, particularly as such influence seemed to many at the time – the height of the McCarthy period in U.S. history – to threaten the security of the United States.

Of course, this was a cynical maneuver by those who already knew that the flyers who confessed to use of biological weapons essentially had told the truth. For them, the issue was how to control the confessors, how to gain retractions, and exploit the situation for the benefit of the United States. They were also concerned with seeking ways to contain secret information from the enemy when military and intelligence personnel were captured in the future. Grotesquely, they hoped to find a way to produce amnesia in their own assets, so secret information could not be passed on to enemy interrogators.

BW and the Air Force Psychological Warfare Division

While the Air Force had a research study on the returning POWs, the Army was conducting its own study as well. The psychiatric evaluations of the returning Army POWs were led by Marine Corps Major Henry A. Segal, Chief, Neuropsychiatric Evaluation Team at Provisional HQ, Korean Communication Zone. The research into supposed Communist indoctrination and the effects of stress in the Army POW experience was contracted out to the Human Resources Research Office (HUMRRO) at George Washington University under the direction of Joseph R. Hochstim, director of the Army’s Psychological Warfare Division. A report was issued in June 1956.

The fact that both Army and Air Force evaluations of returning POWs were run in large part out of their respective Psychological Warfare divisions, otherwise responsible for propaganda and unconventional warfare (including BW itself) creates a huge problem of bias when considering any of their results, both public and those declassified years later.

HUMRRO’s recommendations would lead to the implementation of a stress inoculation model of survival training that later was institutionalized in the Pentagon’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape (SERE) program. The first mock prison training experience using stress inoculation to prepare prisoners for possible torture began in May 1953, earlier than the HUMRRO intervention, when the Air Force opened a “prison camp school” near Chinhae, South Korea. (See this contemporary article also, which dates the Air Force school to May 1954.)

The SERE methods of mock torture used to induce stress inoculation, or resistance to torture and enemy indoctrination, would be adopted by the CIA decades later as part of their “Enhanced Interrogation” torture program in the early 2000s. The CIA and Defense Department had used the 1950s “prison camp schools” as research sites to study and experiment on torture and the application of extreme stressors. One of the primary CIA/DoD researchers working at the then-new captivity survival school sites was MKULTRA psychiatrist Louis J. West, who also worked extensively with the returning Air Force Korean War POWs. His work is described in more detail towards the end of this essay.

Air Force Lieutenant Colonel James L. Monroe, chief of the research branch of the Air Force’s Psychological Warfare Division, and soon to be a major CIA MKULTRA figure, led the research study on the returning POWs, codenamed Project Repair.[1] A rare if vague description of Project Repair was briefly aired in an essay (see pp. 191-192) by George Croker, who had been an officer in the Air Force’s Psychological Warfare Division during the Korean War.

While the Psychological Warfare Division in general was involved in typical aspects of military psywar responsibilities, like dropping propaganda leaflets over the enemy, in 1998, Canadian historians Endicott and Edward Hagerman unearthed a document showing that it also had been involved in the preparation and dissemination of “general Air Force BW and CW policy and program guidance,” as well as the integration of “capabilities and requirements for BW and CW into war plans.” The Division also participated “in the determination of munitions requirements for BW and CW to implement approved plans.”

In other words, until certain aspects of their BW responsibilities were shifted to the War Plans Division in March 1953, the Air Force Psychological Warfare Division — of which Monroe’s research division was a component — had secret responsibility for important aspects of the U.S. germ warfare program.

According to a 1976 U.S. Army book on “The Art and Science of Psychological Operations,” Monroe had been “heavily involved in leaflet drops” during both World War Two and the Korean War, but equally involved in “interrogation” matters (pg. xix). The book doesn’t specify whom he interrogated, but it seems very likely the reference was to the returning Air Force BW confessors, and/or possibly the POWs held in the mock torture camps referenced above.

Monroe came into the Korean War a Major, but one who held considerable fame already. In World War II, he had revolutionized leaflet distribution over enemy territory with his creation of the “leaflet bomb,” dubbed the “Monroe Bomb” in honor of his achievement.

An example of Monroe’s Korean War leaflet activities centered around Project Revere, a study initiated by USAF Psychological Warfare Division director Fred Williams and Colonel George Croker, its “officer in charge,” to assess the effectiveness of propaganda by leaflet drop. Then-Major Monroe was tasked as the Air Force liaison with outside contracting agencies, such as the Washington Public Opinion Laboratory at the University of Washington. This kind of external liaison work became a staple of Monroe’s career in the CIA.

Project Revere was one of the first efforts of the Air Force Psychological Warfare Division’s Human Resources Research Institute (HRRI), which operated under ARDC at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama. It involved, in part, dropping leaflets over portions of the U.S. northwest, and assessing the response to the drops. When the Revere reports came out, they were labeled, “submitted by: Psychological Warfare Research Division, Major James L. Monroe, Chief.”

By April 1956, until he formally retired from the Air Force in February 1957, Monroe belonged to the U.S. Intelligence Advisory Committee through an affiliation with the Air Force Office of Intelligence. He was also a member of the Ad Hoc Prisoners Information Support Committee. The latter concerned Air Force efforts to “support activities to recover U.S. nationals held in Communist countries.”

The Intelligence Advisory Committee, chaired by the Director of Central Intelligence, was a high-level intelligence organization. It included representatives from the Departments of State, Army, Air Force, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Atomic Energy Commission.

James Monroe and The Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology

Monroe left his Air Force sinecure to devote his energies to a new CIA-funded enterprise, the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology (later known as the Human Ecology Fund). The Society originated in the work of two CIA-affiliated doctors at Cornell University, and then expanded further to become a key provider of funding to varied behavioral science and medical projects associated with mind control research for the MKULTRA program.

The Human Ecology Society provided a cover for CIA interactions with dozens, if not hundreds, of witting and unwitting scientists and social scientists in institutions around the country, operating as a cutout for covert intelligence funding. Monroe was their bagman.

His connections went to the very top of the intelligence world. Indeed, Monroe told New York Times journalist Nicholas Horrock in 1977 “that he occasionally briefed C.I.A. directors Allen W. Dulles and Richard Helms on the findings of the [Human Ecology] society.” A short time after leaving the Air Force (if he wasn’t already a covert member of the CIA earlier), Monroe became a leading figure in the CIA’s MKULTRA program as the Executive Secretary, Treasurer, and perhaps at one point Director of the Human Ecology Society.

CIA psychologist, John Gittinger, who was also an officer for the Society, testified in court years later, “I had met Jim Monroe, Colonel Jim Monroe, who at that time [1954] was part of the time on active duty with the Air Force but more often than not was not. And I recruited him to become director of the Society.” (This reference is among many impressive findings in H. P. Albarelli’s 2009 book, A Terrible Mistake: The Murders of Frank Olson and the CIA’s Secret Cold War Experiments.”)

If Monroe wasn’t spending his active duty efforts with the Air Force, one presumes he was too involved with CIA work, or perhaps off-the-books operations with the covert BW program – perhaps assisting Ft. Detrick’s Special Operations Division in reengineering the Air Force’s leaflet bomb into one that dispersed biological agent via feathers or insects, as described further on.

Gittinger was also the creator of the CIA’s Personality Assessment System, which the CIA used for years for interrogations and determinations about the sincerity of double agents and recruits. It’s an open question how and to what degree Gittinger might have been involved with the POWs, but he did tell an Oklahoma newspaper in 1988 that his CIA duties “took him all over the world and involved intrigue and danger.”

In fall 1954, the Project Repair report on the Air Force flyers was delivered to Air Staff. When five years later a public version of the study was published in the journal Social Problems, its author, Albert Biderman, singled out Monroe first for his support. The essay itself was completed with the financial assistance of The Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology, Inc., in other words, of the CIA.

Hence Monroe, the CIA covert funder in his capacity as Treasurer of the Human Ecology program helped finance the government’s public version of the flyers’ experience in captivity. At the same time the Social Problems essay was being published, Monroe was funneling tens of thousands of dollars to psychiatrist Ewen Cameron, who was running highly unethical brainwashing studies — also known as MKULTRA subproject 68 — at Allan Memorial Hospital in Montreal, where Cameron used LSD, barbiturates, electroshock, hypnosis, induced comas, and other wild interventions to produce (they hoped!) permanent amnesias in their subjects, replacing their minds with invented material created by the CIA itself. Dark matters indeed!

Cameron was no obscure doctor grasping at CIA funding. From 1952-1953, he was President of the American Psychiatric Association; from 1958-1959, he was President of the Canadian Psychiatric Association. Three decades later, the Canadian government ultimately paid out millions of dollars for claims of injuries to dozens of Cameron’s victims, and the CIA settled out of court in a lawsuit arising from the Cameron affair.

The case of Linda McDonald was a typical example of the CIA-Cameron brainwashing experiment. McDonald was “a young wife and mother of five children.” Entering Allan Memorial Hospital, part of Montreal’s McGill University, for depression, she was “heavily sedated” prior to the administration of psychological tests. Subsequently, she “was drugged into a coma for two months and thirteen days and subjected to electro-shock and ‘depatterning tapes.’” When her husband complained about the treatment, Cameron threatened McDonald “would be institutionalized for the rest of her life if she didn’t agree to Cameron’s treatment.”

The audio “depatterning tapes” were created by Cameron, and were played over and over for hours and days to the experimental subjects, even as they were in coma, in an effort to implant new memories and feelings. Cameron called this “psychic driving.”

McDonald’s “treatment” at the hands of Ewen Cameron produced profound amnesia. Upon release, “her memory of her past was gone forever.” Linda had never even signed a consent form for her admittance.

According to a 1977 account by Cameron’s research assistant Leonard Rubenstein, Monroe approached Cameron with an offer to his assist his work financially. Of his work with Cameron, Rubenstein told The New York Times, “It was directly related to brainwashing…. They had investigated brainwashing among soldiers who had been in Korea. We in Montreal started to use some [of these] techniques, brainwashing patients instead of using drugs.” Cameron’s initial “depatterning” work had preceded CIA’s sponsorship, but it’s eerie how similar Cameron’s work was to that which emerged from Project Artichoke, which is described further below. [2]

Investigating the Returning POWs

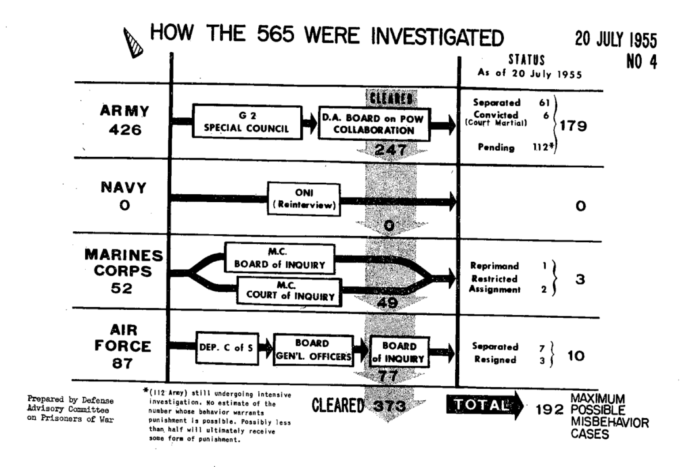

The two charts below provide a general idea of how the investigation proceeded for the supposedly brainwashed POWs returning to the United States at the close of the Korean War. The charts were part of an August 1955 report on the POW controversy submitted to the U.S. Secretary of Defense by a POW “advisory committee.” Chaired by Assistant Secretary of Defense Carter Burgess, a representative from the Pentagon’s Research and Development Board (RDB), on the advisory committee was Edward Wetter, a key figure in the post-World War II amnesty of and collaboration with Japan’s biological warfare unit known as Unit 731.

Wetter was not the only RDB member associated with the POW research. From 1947 to 1949, Dr. Raymond V. Bowers was Deputy Executive Director, then Executive Director of the Committee on Human Resources at RDB, then left to become director of the Air Force’s Human Resources Research Institute (HRRI) at Maxwell Air Force Base, under whose auspices Project Repair was conducted. Bowers, too, was a consultant for the 1955 POW report.

HRRI had been tasked in July 1949, among other things, “with problems of strategic intelligence and psychological warfare operations as relate to the social and psychological vulnerabilities of foreign nations.” Its Assistant Project Director was Dr. Frederick Williams, then the Project Director for the Air Force Psychological Warfare Research Division. Later, Williams would move up to become director of the Psychological Warfare Division itself, and James Monroe would take his place leading the research branch.

The same month in 1955 that the POW Advisory Committee issued their report to the Secretary of Defense, Monroe sent a secret “Special report to the Director of Plans” on “research findings following reception of returned POW [sic] from China.” By 1955 he was already working for the CIA. (So far as I could determine, Monroe’s secret 1955 report has never been released.)

The Advisory Committee’s POW report, which was partly written by pulp fiction writer, Theodore Roscoe, provided some information about the military’s processing of the returning prisoners. As the charts below show, the majority of the returning POWs, nearly 90%, were from the Army. The Air Force and Marine POWs, who each had leading members confess to use of germ warfare, each had less than 225 prisoners.

All POWs were first interviewed by military intelligence, though the accompanying charts and the 1955 report from which they derive never mention CIA, OPC (Office of Policy Coordination), Army Criminal Investigative Division (CID) or CIC (Army Counter-intelligence Corps) interrogations, all of which took place. In at least one case, described below, a key POW’s retraction of his BW confession was guided through and edited by a CIC officer. It can be assumed that was not the only time that occurred.

According to one historical account of the 426 or so U.S. Army POWs investigated for collaboration or other suspicions of enemy influence, “court martial charges were prepared against 82 of them” (p. 194), while the Army Security Review Board approved 47 for trial. Ultimately eleven men were convicted by court-martial, out of 14 who finally went to trial.

As one can see from the charts reproduced here, as late as summer 1955, nearly 200 ex-POWs still had possible charges hanging over their heads. Of the Air Force returnees, who were largely better educated and older than the Army POWs, 77 out of 87 were sent on after initial evaluations to an Air Force Board of Inquiry. Ten were pressured or found it otherwise prudent to resign their commissions, or were separated from work supervising others.

CIA Research on Interrogation and Mind Control: Project Artichoke

The U.S. military and CIA had already begun their own mind control research programs prior to the appearance of the germ warfare “confessions.” Project Bluebird operated as early as 1948, and involved experiments in interrogation using drugs and hypnosis. By 1953, Bluebird had morphed into Project Artichoke, which expanded the use of interrogation experiments to include electric shock, LSD, barbiturates, amphetamines, and other substances, with the aim of achieving total control over another human being.

Artichoke in particular was obsessed with creating amnesia in its subjects. As former State Department intelligence analyst John Marks wrote in his famous book, The Search for the Manchurian Candidate, “Inducing amnesia was an important Agency goal. ‘From the ARTICHOKE point of view,’ states a 1952 document, ‘the greater the amnesia produced, the more effective the results.’”

The Artichoke experiments in interrogation specialized in sedating subjects with barbiturates (including the purported “truth drug” sodium amytal), scopolamine, alcohol, and other central nervous system depressants, and then injecting subjects with Benzedrine, methamphetamine, or other stimulants, while also subjecting the person to hypnosis, sensory deprivation, and electroshock. Other drugs were used as well, most famously LSD. One description of the Artichoke “method” can be read in CIA files.

Finding suitable candidates for experimentation wasn’t easy. Prisoners seemed ideal, as they lacked freedom, and were fully controllable, although U.S. prisoners presented some difficulties around the issue of “informed consent.” But experiments on foreign prisoners could be kept far from prying eyes, especially needed in the years following Nuremberg. In his book (pg. 19), Marks stated that in October 1950 “advanced” Bluebird techniques were applied to 25 North Korean prisoners of war.

Counterpunch founders Jeffrey St. Clair and Alexander Cockburn explored the issue in their 1998 book Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs, and the Press. In a recently excerpted portion of the book St. Clair and Cockburn explained, “The CIA memos of the time are filled with complaints about the difficulties of finding suitable human subjects for experimental research. ‘Human subjects’ were evoked in the tactful phrase ‘unique research material.’”

The emphasis on prisoner research also surfaced in a January 1953 report by a CIA Ad Hoc Medical Study Group:

“For investigations designed to improve methods of interrogation, study under field conditions and near depots of recently captured prisoners of war is strongly recommended. The opportunities now made available by the situation in Korea should be immediately utilized by assigning appropriate research teams with adequate freedom of movement for this purpose.” (bold emphases added)

But it was one thing to use drugs, hypnosis, and other forms of psychological torture on foreign prisoners — as illegal and unethical as that was — and another thing to use it on returning U.S. prisoners of war.

When the POWs who confessed to BW warfare returned to the United States, they were all reported to have retracted their wartime confessions. If one believes the U.S. government, the prisoners had all been tortured or brainwashed, and once returned to freedom, turned on their previous captors and denounced them, while disavowing their statements about germ warfare as pure fantasy.

In his recantation, former Chief of Staff for the First Marine Air Wing and the highest ranking Marine Corps officer captured during the Korean War, Colonel Frank Schwable, depicted his statement to Chinese interrogators as “this false, fraudulent, and in places absurd confession.” (Link, p. 54) But according to a sympathetic account of Schwable’s incarceration and later investigation by U.S. authorities by independent researcher Raymond Lech, Schwable “revealed quite a bit of classified information” (p. 157–158).

CIC and the POWs Who Confessed to Germ Warfare

While later in this article we will examine in more detail intelligence figures involved in “processing” the returning BW POW “confessors,” it is worth pursuing here the fact that Schwable’s recantation was constructed under the supervision of Lt. Col. (LTC) Robert Matthews. Matthews was chair of the Joint Intelligence Processing Board on the MSTS Howze, which took the flyers back to the U.S. from South Korea. The Board included a psychiatrist, a psychological warfare expert, a military attorney, CIC representatives and other senior officers. With 51 Air Force POWs on board, out of a total 288 prisoners on the ship, Matthews had authority over twenty of the “confessors.”

According to Lech’s account, two days out of port, Matthews gathered all the ex-POWs together, including Schwable, for a “security briefing” where they were told, in Lech’s words, “not to speak with anyone outside their cloistered community” (pg. 144 of Lech’s Tortured into False Confession).

Matthews had served in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the World War II forerunner to the CIA. According to the biography of Frank Schwable by the late Raymond Lech, after joining CIC in 1948, Matthews became liaison officer between the 441st CIC detachment and the section of Army military intelligence (G-2) concerned with counterintelligence.

Based in the Presidio in San Francisco, California, Matthews’ boss must have known or answered to Colonel Boris Pash. Pash, who in January 1976 was called before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence to answer questions raised from testimony from Watergate figure E. Howard Hunt about Pash’s involvement in a CIA assassination unit in the late 1940s, had been Chief of the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division (CID) at the Presidio at the time of the return of the POWs.

According to historian Judith F. Gentry and former Korean War POW, John W. Moore, CIC coordinated with CID in the interrogations of the returning men and made recommendations about possible prosecution. Pash had a long history in government security and counter-intelligence. He had been chief of counterintelligence for the top secret, atomic bomb Manhattan Project, and subsequently was picked to lead the clandestine Alsos Mission that searched for Nazi scientists at the end of World War II.

Ian Sayer and Douglas Botting wrote in their history of CIC that Pash was the Army representative to CIA’s Operation Bloodstone, a covert operation seeking to recruit former Nazi collaborators to work for U.S. intelligence against the Soviet Union. In March 1949, he was attached to the OPC portion of the CIA, a semi-autonomous section involved in covert actions on behalf of the National Security Council, including assassinations. With a career going back to battling the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War, Pash was a colorful, and deadly serious figure in U.S. intelligence. His activities, placing him in close proximity and position of authority in regards to the return of the confessing POWs, still remain only vaguely drawn.

According to LTC Matthews, the evening before docking in San Francisco, Col. Schwable came to him and asked if he should submit a statement about why he signed his BW confession. Schwable had noticed that while aboard ship all the Air Force flyers who confessed to BW had prepared retractions to their confessions to their Chinese captors, and Schwable had begun working on one, too. Matthews told Raymond Lech that he advised Schwable to write what he wanted, but “anything that he said or wrote could be used against him in a court-martial” (pg. 147, Tortured Into Fake Confession).

One wonders if at that moment Schwable recalled what he had written in his BW confession to the Chinese. Regarding the security measures surrounding the BW campaign being waged in Korea and Northeast China, Schwable wrote: “Violations of security in this matter, like violations of security of any regulation of equal importance, were to be the subject of a general court martial.”

According to Lech, Matthews felt Schwable’s retraction statement was inaccurate in many details. Schwable told Matthews he thought his own work was “chopped up” and not ready for submission. It was full of scribbled side comments, scratch outs and corrections. Matthews offered to have CIC fix it up. He took the draft statement back to where the Joint Intelligence Processing Board had its administrative offices and had typists work on it. Matthews and another officer proofed it and made pencil corrections. The next day, he showed the new draft to Schwable, who approved the reworked draft.

While we can’t know for certain how much CIC’s Matthews shaped the Schwable retraction — unlike the other retractions, it has a lot of psychological verbiage in it — we do know from Matthews’ own interviews with Lech that all of the retractions written came under threat of prosecution.

Matthews said he was certain that when he met with Schwable he “implied he [Schwable] was being investigated for collaboration in a treasonable manner.” Matthews indicated he told him this more than once. Matthews also told Lech that as senior officer he instructed other staff that “right from the beginning, each soldier or airman was to be warned, prior to interrogation, that he ‘was suspected of an offense that did involve collaboration in a manner which could be considered treasonable in that it rendered aid and comfort to the enemy’” (p. 148).

The airmen’s retractions were not unforced. It appears that all of the depositions signed by the BW confessing flyers, renouncing their previous statements about use of germ warfare, were made under implicit or explicit threat of prosecution for treason.

There was still the matter of Schwable’s original “deposition” (confession) to the Chinese, which, according to Lech’s account, “reeked with” classified material, including the names of his commanding officers; the bases and geographic locations of Marine Aircraft Groups 12 and 33; provision of sensitive order of battle information; classified locations of air bases, and more.

It’s no wonder that military intelligence and the CIA were perturbed by the flyers’ revelations. Despite strenuous U.S. denials, the POW confessions were, according to an official Marine Corps history, “unquestionably damaging.”

Meanwhile, back on board the Howze, there was anxiety and fear, and perhaps some paranoia. Former high-ranking POW and BW confessor, Air Force Colonel Walker Mahurin wrote in his autobiography, “ the specter of a court-martial seemed to be ever-present” (p. 375–376). In fact, it wasn’t clear to Mahurin that he wouldn’t be charged for treason or a similar offense until he was finally formally cleared in May 1954.

Three days after leaving Korea by ship back to the United States, Mahurin’s written retraction of the BW charges was submitted to “a psychological warfare [PW] officer on board — a man who was to take depositions from all of us who had made germ-warfare confessions” (p. 348). Apparently this PW officer did not approach Marine Corps Colonel Schwable, leading me to believe that he was from the Air Force, as were all the other confessors on the Howze. Marine Corps Major Roy Bley had been taken to a hospital after his release, and it is not known how his retraction was obtained.

Mahurin described how, after undergoing a horrific (and suspicious) auto accident soon after his return to the U.S. mainland, he underwent two weeks of interrogation by the Air Force Office of Special Investigations. Among other things, Mahurin was asked to inform on other prisoners. Mahurin was indignant at the request, but in fact, according to Gentry and Moore, some of the returning POWs indeed informed on other POWs.

The retractions of Walker Mahurin and Frank Schwable, and a number of other POW confessors, can be read online. In all, only six affidavits of retraction, out of an approximate 25 public depositions or confessions made by Air Force and Marine officers, were published or distributed by U.S. officials. This compares to the twenty-one released statements published by China of U.S. prisoners admitting to involvement in the BW air war. (Another four such “confessions” were included in the appendices of the September 1952 report by the International Scientific Commission for the Investigation of the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in Korean and China [PDF – pp. 491-592 of the document, or pp. 588-681 in PDF numbering]).

CIA Plans Interrogation Experiment on POWs at Valley Forge Hospital

On April 29, 1953, Associated Press reported that some POWs associated with the initial “Little Switch” exchange of prisoners between the U.S./UN forces and China/North Korea were to be sent to Valley Forge Army Hospital in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. The U.S. government was concerned, the article stated, “over the possibility that standard Communist propaganda efforts, as well as unique psychological devices, might be used on men destined for exchange.”

All told, the “Little Switch” release of prisoners amounted to 684 prisoners. The released POWs had gone from the POW camps to U.S. custody, where they were airlifted by helicopter to an Army Evacuation Hospital near Seoul, Korea. They received a physical and were sent on to Tokyo, where they faced a hasty medical and psychiatric examination.

According to Dr. Henry A. Segal’s November 1954 article, "Initial psychiatric findings of recently repatriated prisoners of war," published in the American Journal of Psychiatry Vol. 111, No. 5, as one of the doctors in charge of the POWs medically, Segal felt the men appeared to have been influenced by the Communists. “There was considerable confusion expressed as to who really started the Korean War. The majority believed that our forces had actually used germ warfare although most of the men felt ‘it was all right for us to do that in a war’” (p. 360).

That meant that there were many POWs convinced of the truth of the germ warfare charges, a fact rarely if ever addressed in writings on the subject. Somehow these men would have to be disabused of such a belief. The Valley Forge experience seemed ready made for that, as did the machinations of the CIA’s Artichoke team.

The initial screenings in Seoul and Tokyo had revealed prisoners who the military and the intelligence agencies thought had turned Communist “hard-core.” Others were believed under the influence of Communist indoctrination, while a third group appeared neutral. A decision was made to ship some of the prisoners under heavy security straight from Tokyo to Valley Forge Army Hospital in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. The former U.S. POWs sent to Valley Forge — some 22 of them, none of whom had been involved in the BW confessions — were destined for “‘psychical’ as well as medical treatment,” and there was no way of knowing how long that treatment would take.

Meanwhile, on the same day news of the transfer was publicly reported (April 29), the Chief of CIA’s Office of Technical Services, Sidney Gottlieb, was writing a memo describing “proposed activities” for an Artichoke intervention on the returning Valley Forge POWs. Some of the details of the Valley Forge Artichoke project were publicized in the 1970s when the CIA declassified the records under a Freedom of Information Act request from the Center for National Security Studies. For instance, this August 5, 1976 Washington Post story by Austin Scott (link – PDF pg. 10 in a CIA release) explicitly singled out the CIA-Valley Forge link. Nevertheless, there were a number of important details that went unreported. The story as a whole dropped out of the public’s consciousness over the years.

According to the Gottlieb memo, Artichoke was “interested in handling through its various techniques,” returning prisoners it described as “hardcore” — that is, converted to Communism — as well as others “who have been exposed to and accepted in varying degrees Communist indoctrination.” The Agency was concerned about Communist penetration agents, and “exposure of secret instruction for contacts, missions, etc.”

“Cover in this situation is perfect — a pure medical cover in a controlled area,” Gottlieb wrote.

CIA Liaison with the Pentagon BW Panel on Projects Bluebird and Artichoke

The CIA was not unfamiliar with Valley Forge Hospital. The minutes from a May 23, 1951 meeting of the Project Bluebird team discuss the past history of Valley Forge in conducting “extensive psychiatric work” during World War II. “They might be able to give us the names of doctors who were on their staff at that time, and might be available” for Bluebird work, CIA officials thought. One colonel was asked to reach out to the Surgeon General’s office in this regard.

The Bluebird/Artichoke project had significant outreach and cooperation with the Pentagon. The May 1951 memo stated that when it came to Bluebird’s work, “Coordination with the military on the highest possible level will be effected…. Meeting [sic] of this committee with the military designees will be held ad seriatim” [“one after another,” or in a continuing series].

A November 26, 1952 memo to Gottlieb and the Chief of CIA’s Medical Staff from the Agency’s Security Office, which had assumed responsibility for Project Artichoke, specifically detailed Artichoke liaison to the Pentagon’s Research and Development Board (RDB). “Liaison with the Research and Development Board in support of this Project will be the responsibility of OTS [Office of Technical Services] under an arrangement already effected by OTS,” the memo said. OTS was Gottlieb’s department, and heavily engaged in mind control and interrogation research.

RDB had been intimately involved in the U.S. amnesty granted to Japan’s biological warfare department, Unit 731, headed by Lt. Gen. Shiro Ishii. RDB was constituted of numerous subcommittees, including a Committee on Biological Warfare.

The RDB secretary for a special 1950 Defense Department study that recommended dropping a “retaliation only” policy for use of biological weapons, Edward Wetter, was a key figure in the push to grant amnesty to Ishii and obtain the data gained from Ishii’s experiments on BW, which were inflicted with inevitable fatal results on thousands of prisoners in Manchuria in the 1930s and early 1940s.

Wetter was deputy executive director of RDB’s Committee on Biological Warfare, and its point man for various working “panels” of that committee, including its “Panel on Man,” “Panel on Crops,” and “Panel on Intelligence.” Hence the U.S. government’s promise to Ishii to hide his work and collaboration with the U.S. biological warfare program inside “intelligence channels” in some measure rested on Wetter’s shoulders. Indeed, nowhere in any of the Chemical Corps documents from this period is there any reference to the work of the Japanese biological warfare project or the U.S. appropriation of it. (Wetter’s collaborator in the work on Ishii’s amnesty was Dr. H. I. Stubblefield, who would serve as the Army representative on the Committee on Biological Warfare’s “Panel on Crops.”)

Meanwhile, the Pentagon’s biological weapons advocates had their own representative on CIA’s Artichoke committee. In his 2020 book, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act, author Nicholson Baker revealed that Harvard/MIT scientist Dr. Caryl Haskins, who had been an adviser to RDB and headed his own 1949 study for the Pentagon on using biological weapons, was himself a founding member of Project Artichoke.

“As part of the CIA’s search for improved means of interrogation and more effective mind-control drugs, Haskins helped the Agency recruit a team of scientists and psychiatrists…” Baker wrote (pg. 21). (Baker’s book is a cornucopia of information on the kinds of material discussed in this essay. He also covered the Valley Forge POW scandal in his book, without however apparently knowing about the CIA Artichoke connection.)

Haskins’ 1949 committee to study BW followed upon the work of an October 1948 study for the Research and Development Board by Dr. William A. Noyes, Jr. The Noyes Report undertook a comparative examination of the possible military benefits of chemical, biological, and radiological weaponry.

The portion in Noyes’ report on BW did not impress the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who were the study’s primary audience. The JCS felt they still did not have enough technical information to pass judgment on the usefulness of BW weapons. The restriction of BW and chemical weapons to retaliation use only was also a constraining variable. Meanwhile, the Chemical Corps had to admit that even in 1949 it could not yet “offer the Joint Staff what it considers a really satisfactory BW weapon.”

Yet in a January 1959 filing in Federal Court, John Schwab, the former director of Ft. Detrick’s Special Operations Division during the Korean War, stated under oath that the U.S. had offensive BW capabilities as early as January 1949. Perhaps Schwab war was referring to armament capability secured from Unit 731. We just don’t know.

Noyes was an entomologist, and Chairman of the Chemical Corps Advisory Board. According to a surviving set of minutes from a February 22, 1948 meeting of the CC Advisory Board, Noyes approved a recommendation that the Chemical Corps explore insect vectors in weapons for the delivery of biological agents. It seems likely that the collaborative work done with Japan’s scientists from Unit 731, recruited by the U.S. after the war, had something to do with this recommendation.

Noyes also noted that work on offensive use of insect vectors was already underway in “other government agencies” under the guise of “insect control.”

With the JCS demurring on a major commitment to BW research and development as presented in Noyes’s 1948 report, Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, a supporter himself of the potential of biological warfare, turned around and formed a new “Ad Hoc Committee on Biological Warfare.”

The Committee included, according to one scholar, “the most active supporters of BW work.” These included General Alden Waitt, Chief of the Army Chemical Corps, responsible for recommendation of biological weapons research to the JCS, and Dr. Ira Baldwin, Chair of the Bacteriology Department at the University of Wisconsin, and the author of a 1947 report for RDB’s Biological Warfare Committee that positively portrayed the potentials for BW research.

Dr. Haskins, a biophysicist who was also an expert in entomology and radiation, who had founded his own successful research laboratory, was the Chair of Forrestal’s new committee. (Forrestal would not live to see the committee’s report, as he died from either suicide or foul play in May 1949.) When Haskins’ report concluded that more resources be allocated for BW research, the new Secretary of Defense, Louis Johnson, constituted yet another ad hoc committee to explore the use of biological, chemical, and radiological weapons.

This next ad hoc committee was chaired by Earl Stevenson, President of Arthur D. Little, Inc. The new committee was extensively briefed on BW work at Camp Detrick, and also received input from various members of CIA staff. The Stevenson committee submitted its report to the Secretary of Defense a mere five days after the start of the Korean War. It advocated strongly for pursuit of biological weapons, including an end to the use of the “retaliation only” policy. The Stevenson Committee’s recommendations began what was widely discussed at the time as a “crash program” in BW.

As regards Caryl Haskins, his dealings with the CIA preceded what Baker found. Not only was Haskins involved in the Artichoke program, he apparently was aware of and possibly helped foster the earlier Bluebird program as well.

According to a May 31, 1949 memorandum from FBI Assistant Director D. M. Ladd to Director J. Edgar Hoover on the subject of “Biological Warfare,” at a May 14 meeting of Haskins’s Ad Hoc Committee on Biological Warfare, two CIA officials from the Agency’s Scientific Branch gave a presentation on top secret work the CIA was doing on interrogation.

One of the CIA presenters, Dr. Willard Machle, was Chief of CIA’s Scientific Branch, and most likely also a member of Haskins Ad Hoc Committee. What was bizarre about this presentation, besides its content, was how CIA mind control work was part of the U.S. biological warfare project from the very beginning!

The May meeting included “guests” like Dr. Irving Janis, Yale Department of Psychology, and Dr. A. H. Corwin, Director of the Chemical Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. Only a month before, Janis had authored a report for the Rand Corporation on his belief the Soviets were using hypnosis to implant memories in people. Hypnotic techniques, Janis hypothesized, were being used “by police agents… to produce false confessions” (p. 3).

Machle and his co-presenter, G.C. Backster, Jr., told the Committee that the information on the CIA’s interrogation research “was very closely held and this Committee was the first group outside of CIA to be informed of the project.” Even the FBI and the Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps had not been briefed on it, the CIA having withheld queries for the cooperation of other government agencies until “techniques for positive control of the experimental subjects had been validated.” Machle said he expected such validation would was not too far off. He wanted the Committee’s “support for a program of vigorous exploration of these techniques.”

The techniques, about which the Committee “expressed considerable interest,” concerned “various methods of isolation of the subconscious mind… particularly in the use of drugs as an aid to hypnotic techniques.” (You can almost see Dr. Janis vigorously nodding his head at this.)

According to the minutes of the meeting, which was – it is worth recalling – organized to study the potential of biological weapons as a means of unconventional warfare, including sabotage, we read this (pg. 2):

Several possible uses of such techniques by unfriendly parties were covered [in Machle’s presentation]. These uses included the extraction of classified information from an individual through subconscious isolation and detailed interrogation through regression. A simple means for the reproduction of the subconscious state was explained and the process of subconscious assignment covered, pointing out the possibilities of espionage and sabotage guidance by U.S. personnel through domination by foreign technicians. The possibilities of instilling of false information into, and the eradication of information from the conscious memory were cited. Details were given concerning negative visual hallucinations and the surveillance possibility involved. The possible destruction and the re-creation of personality and character traits were explained.

According to an undated CIA document (see a transcription of this document for greater clarity), “subconscious isolation” was a “method of exerting immediate or prolonged influence on the subconscious mind.” Induction of “subconscious isolation” was via use of “fixed attention” (hypnosis), “emotional stimulation” (possibly threat, or what CIA called “emergency”), drugs (including “Surreptitious administering”), “Sleep conversion,” and “Shock treatment” (both insulin and electrical).

The language of the terminology (“subconscious isolation,” “regression”) indicated that the CIA saw the mind as composed of substructures that could be dissociated from each other, and that such dissociation occurred when a subject was in a physical or psychologically regressed state. This is consistent with theories of neuropsychology then known, and also with the psychoanalytic theories of Freud and his followers.

The theory of the CIA mind control psychologists and psychiatrists was that the dissociable portions of the subconscious mind could then be isolated, manipulated and controlled via use of hypnotic measures, while nervous system shock, or states of normal human regression (like sleep), or use of drugs, were used to spur the initial dissociation. Covert commands and false memories then could be inserted into the mind via hypnosis, and discrete or global amnesias created. Meanwhile, CIA worried greatly that U.S. adversaries would discover this, or had already discovered this. The preoccupation of the CIA with mind control has never disappeared.

Adding to this account (both Baker’s and my own) of the intersection of the U.S. biological warfare work with CIA’s mind control program, the minutes of a June 1953 Artichoke Conference meeting referenced “the work of the Army Chemical Corps in lines of interest to ARTICHOKE” (all caps in original).

The Army Chemical Corps was the agency that ran Ft. Detrick, center of the U.S. biological warfare program. Buried deep within the facility was a joint CIA-Chemical Corps unit, the Special Operations Division, where, as Baker described, the E-74 BW feather bomb was created, and other “means and mechanisms for the covert dissemination of BW agents” (pg. 75, Baseless).

The E-74 (also known as the M115) feather bomb had been developed from the military’s 500-lb. leaflet bomb, which was used by the Air Force’s Psychological Warfare Division to drop millions of propaganda leaflets over North Korea. The leaflet bomb itself was developed in World War II, and known in the military as the “Monroe bomb,” after its creator, James L. Monroe, the same man who later was in charge of the investigation into the Air Force flyers who confessed to germ warfare.

As we have seen, a few years after the Korean War, Monroe would supervise the CIA grant for the work of notorious MKULTRA contractor, Dr. Ewen Cameron, whose experiments in “psychic driving” and “depatterning” were the very model of CIA’s own attempts at a “brainwashing” paradigm, using drugs and electric shock and hypnosis, along with subliminal tape instructions inserted into people during long forced periods of sleep. For its surviving victims, it was a living nightmare.

Monroe and Joint Air Force-CIA Operations: the ARCS Scandal

When the State Department sent the copies of a half-dozen retraction affidavits from high-profile POW confessors to the UN in December 1954, the packet included sworn statements by Monroe about the use of the Air Force leaflet bomb being solely for propaganda distribution of leaflets only. Monroe’s efforts were, at least temporarily, exposed on the world stage. They showed him to be intimately involved in high-level Air Force matters, and also, though not mentioned at the time, in joint CIA-Air Force operations.

The State Department’s submission to the UN was related to another prisoner of war controversy, this one stemming from the January 1953 shoot-down and capture of Colonel John K. Arnold. Arnold was Commander of the 581st Wing of the U.S. Air Force’s Air Resupply and Communications Service (ARCS).

According to a 2008 article in IO Sphere, published by the Office of the Joint Information Operations Warfare Command, during the Korean War ARCS’s air wings “were actually operational arms of the Psychological Warfare Division, Directorate of Plans, HQ Air Force – and charged with planning Air Force Psychological Warfare, Conventional Warfare and Special Operations.” But “ARCS was not so much to support PSYOP in Korea, as it was to scratch the itch of the fledgling CIA who needed air support for agent operations” (p. 8).

The links between the Air Force’s ARCS and the CIA, which was dropping agents and guerilla forces behind enemy lines in China and North Korea, were revealed in newspaper reports in 1998. While Arnold was supposedly not CIA himself, he apparently admitted to Chinese interrogators his cooperation with CIA air incursions into China. His confession was another embarrassment for the United States.

A month after China sentenced Arnold to prison in November 1954 for spying for the CIA, the U.S. State Department delivered a package to the UN that was meant to prove that Arnold’s ARCS crew were not “spies,” and that their plane was on an ordinary leaflet drop mission. Backing Arnold’s defense were statements by Lt. Col. James L. Monroe, USAF.

Monroe’s statement showed top-level knowledge of the joint operations of Japan Air Defense Force, Far East Air Force Bomber Command, and the activities of the 581stARCS Wing. His bona fides were guaranteed by no less than Secretary of the Air Force, Harold Talbott, who stated Monroe was “the officer within the Air Staff having cognizance of planning and operational matters concerned with” the ARCS flights.

Although CIA’s links with ARCS weren’t admitted in the West until 45 years after Arnold’s capture, the episode starkly reveals Monroe’s participation in joint USAF-CIA operations. At the same time as he was in the top leadership of the Air Force effort to assess and deal with the Air Force POWs BW confessions.

The leaflet issue was sensitive. In April 1952, House Representative Robert Sikes (D-FL), fresh from a House Appropriations Committee meeting with Major General Egbert Bullene, Chief Chemical Officer of the Army Chemical Corps, told the press that “containers used currently for dropping propaganda leaflets” could be used to deliver biological munitions, negating the need for any “super-weapon” for “retaliatory bacteria warfare.” Moreover, the military was “well-stocked” with such containers, Sikes said. He could only have heard this from Bullene. Chinese and North Korean authorities were quick to notice the admission, as this video shows.

The “Standard” Artichoke Approach

With the return of some 22 (some reports say 21) POWs to Valley Forge at the beginning of May 1953, the Artichoke team was proposing “a standard pentothal-Desoxyn-type approach,” that is, drugging the former prisoners, now patients, with sodium pentothal and methamphetamine, followed by hypnosis (either under sedating drugs or “direct hypnosis”). The team also recommended use of a “new special chemical,” whose name is whited out or unreadable in the CIA documents.

This new chemical was described as producing “disorientation, confusion, talk, expansiveness and other peculiar phenomena.” It had been tested already on “40 normal subjects and a large number of schizophrenic patients,” with “no fatalities, no trouble indicated.” The new drug was “colorless, odorless, tasteless and soluble in water,” and “could be successfully concealed in common liquids.”

Gottlieb proposed a seven-man team, including a “top-flight anesthesiologist,” a hypnosis consultant, and an “observer” from an agency or group that is redacted in the memo, who could “act as consultant and give advice in the use of the [new] chemical.”

The drugs would be given intravenously. “Various drugs” would be administered after the Pentothal. It was, according to the CIA, a “modified ‘truth serum’ approach,” which had been used “successfully” before. “Direct questions, regression, reorientation, etc.” would all be attempted. Artichoke sessions lasted 2 to 4 hours. Gottlieb thought the team could handle maybe three “subjects” a day.

It was a taste, perhaps, of what the confessing Air Force POWs could expect when they were returned later after hostilities ended. But the Valley Forge experiment was cancelled, although as two CIA documents suggest (see below), it was only delayed by some months. Still, what the POWs faced upon arrival at Valley Forge was bad enough. They were flown to Pennsylvania in a plane with barred windows. No contact with reporters was allowed. When the plane had to stop en route in California, it was “surrounded by MPs with tommy guns,” according to a May 12, 1953 memo for the record by the CIA’s Horace Craig, working at the high-level, multi-agency Psychological Strategy Board.

Craig was concerned about the over-the-top security surrounding the returning POWs because such repressive actions “corroborated what the enemy had told” the prisoners to expect when they were returned to the U.S. Subsequently, news reports corroborated what Craig discovered in his investigation of the repatriated POWs. They felt “extremely bitter and bewildered — and, in some instances, literally frightened” about what was happening to them. The Valley Forge doctors were worried that “serious emotional upsets would ensue.”

Craig had rushed to Valley Forge to smooth things out. But his memo on the visit never mentioned the Artichoke experiment. It did, however, give some insight into what was happening behind the scenes.

“Where all the confusion in the repatriation program really started is most difficult to determine,” Craig wrote. He bemoaned the fact that no one group in the Defense Department seemed to really be in charge of POW matters. Nevertheless, he supported the POWs sequestration. “It is my belief that there was a need for this program in order to find out what we have found out concerning this particular group” (emphases in original).

In the end, the Artichoke treatment for the returning Korean POWs was (supposedly) called off because, as one CIA memo put it, “extreme pressure of public opinion both in the military services and in Congress had interfered with a well-worked out program in connection with the POWs.” The CIA/Artichoke representative at Valley Forge met with military intelligence and the Surgeon General’s office representatives regarding CIA’s plans to use drugs, but “this had been ruled out completely by the Surgeon General’s office.” CIA still was involved, however, providing “technical equipment” for the military intelligence interrogators (a fact left out of the 1970s press articles on the subject).

CIA Briefs FBI on Valley Forge Interrogations

Was the Valley Forge debacle really the end of the POW Artichoke experiments? Apparently not, for two weeks after the major repatriation of U.S. POWs from Communist prisoner of war camps began – the “Big Switch” exchange of prisoners – the minutes of an Artichoke Conference on August 20, 1953, described a trip undertaken by two CIA officials, one on whom was from the Agency’s Security Office (Artichoke’s supervising department at CIA).

The officials were “on a trip involving interrogation of returning POWs from Korea.” The purpose of the trip was to learn more about “so-called ‘brain washing’ techniques by the Communists,” while “planning to use this information in connection with” some upcoming Artichoke operation.

The official with the Security Office may have been its chief, Morse Allen. The other official may have been a CIA-affiliated psychiatrist known to CIA Technical Services Division Chief Sidney Gottlieb, namely Dr. Louis Joylan West, whose work was analyzed in Tom O’Neill’s 2019 book, Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties, published by Little, Brown and Company.

Further corroboration that the Artichoke experiment in interrogation ultimately went forward at Valley Forge can be found in a June 16, 1953 FBI memorandum for the record from Associate Director Clyde Tolson to Assistant Director D. M. Ladd.

Tolson recalled how he, Ladd, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, and a “Mr. Belmont” (probably Alan Belmont, head of the FBI’s Domestic Intelligence Division) attended a meeting about the brainwashing of U.S. prisoners and the acts of “treason” they entailed. The meeting was called by the CIA and held at the office of the Attorney General in Washington, D.C., with CIA chief Allan Dulles as chair.

The CIA screened a film of the confessions of four U.S. flyers to the use of biological weapons in the Korean War. The film was obtained, CIA said, in South America, and was “being shown throughout the United States.” The confessions contained “considerable detail,” though “the statements of the prisoners were obviously incorrect.” After each individual flyer’s statement, the film was stopped for discussion, while “an associate of Joseph Bryan III” briefed the group.

As will be discussed further below, Bryan was both a prominent member of the CIA’s blandly named covert action branch, the Office of Policy Coordination, and a good friend of captured U.S. Air Force Colonel Walker Mahurin, one of the highest-ranking flyers to confess to use of BW.

According to Tolson, “The CIA representatives also advised they had obtained considerable information from Valley Forge, where a number of the prisoners who appeared to have been indoctrinated were originally taken….”

The CIA told the FBI that interrogations showed there were “a number of ‘hard-core’ Communists who had been in the American army and who seemed to have taken over the direction of the prison camp and to be assisting the Chinese Reds in the indoctrination and discipline of the American prisoners of war.”

But all other evaluations, including that of the Psychological Strategy Board, and internal CIA discussions showed there were barely any “hard-core” Communist prisoners, and I’ve not seen one other source that claimed that U.S. leftist prisoners took over “the direction of [a] prison camp.” Dulles had to know this. Perhaps he was playing to Hoover’s Red paranoia. In any case, the Tolson memo showed that the CIA’s Artichoke project on the Valley Forge Little Switch prisoners was never completely abandoned.

CIA-Affiliated Doctors and Psychologists Who Worked with the POWs

In the final portion of this article I will briefly describe the primary CIA-affiliated doctors and psychologists who had a specific relationship with the POW issue, particularly in relation to those POWs who had confessed to U.S. use of germ warfare. It’s not a definitive list, and there may be important figures left out. (For instance, Dr. Harold Wolff is not separately discussed below.) Nor is each capsule listing below meant to be a major evaluation of that person’s career, as most of these individuals went on to have many more projects, accomplishments, and even controversies, to their credit or discredit.

Also, and surprisingly, I will consider the CIA and high Pentagon connections of Walker Mahurin, one of the Air Force POWs who confessed to participation in the BW campaign.

As we examine the following individuals, readers can gain a more detailed view of how the POW studies and interventions unfolded among the military and intelligence bureaucracies involved.

Louis J. West, MD

In an excerpt from his book published online at The Intercept, author Tom O’Neill pointed out West’s association with the studies and interventions on the returning airmen who confessed to germ warfare. O’Neill wrote that West and his colleagues who examined and studied the returning flyers got the flyers “to renounce their claims about having used biological weapons.”

But there is no documentation that West was on board the ship where the flyers recanted their confessions within days of repatriation under threat of prosecution and fear for their future. Or was West there from the very beginning, part of Project Repair or even more secret interventions with the POWs – like Project Artichoke? While O’Neill’s book can’t answer every question, it does have a lot of information about West’s career.

O’Neill traces West’s collaboration with Sidney Gottlieb back to at least as early as June 1953, when West proposed to the chief of MKULTRA “a plan to discover ‘the degree to which information can be extracted from presumably unwilling subjects (through hypnosis alone or in combination with certain drugs), possibly with subsequent amnesia for the interrogation and/or alteration of the subject’s recollection of the information he formerly knew.’”

West had a plan to use “techniques for implanting false information into particular subjects … or for inducing in them specific mental disorders.” This was pure Artichoke material, whether West knew about that secret project at that point or not.

According to O’Neill, who had access to West’s papers at UCLA, Gottlieb was “grateful,” and told the young military psychiatrist, who then was chief of the psychiatric service at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, “you have indeed developed an admirably accurate picture of exactly what we are after.” For his part, West asked for “some sort of carte blanche” to conduct practical trials in the field.”

Five years later, at a presentation for a symposium on “Methods of Forceful Indoctrination,” held at the Berkley-Carteret Hotel in Asbury Park on Veterans Day, 1956, West presented on the “Air Force Prisoners of the Chinese Communists.” At the time, West was working with an associate, I.E. Farber at the University of Oklahoma, on “POW studies now underway… concerning Prisoners of War and their reactions to various types of stress” (p. 270). West’s discussant on the panel was Monroe’s colleague, CIA doctor Lawrence E. Hinkle, who was an associate professor at Cornell University Medical College, as well as Vice President of the CIA’s MKULTRA cutout agency, The Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology.

West’s emphasis on the effects of stress on prisoners and the study of survival school subjects under controlled conditions of mock torture continued as a CIA and Pentagon research program into the 21st century, as evidenced by the work of Yale psychiatrist Charles A. Morgan, III, who has worked for the CIA and U.S. Special Operations Command. Morgan has published his findings from such research in the American Journal of Psychiatry and elsewhere.

Back in the 1950s, Dr. West was Chief Investigator with the “Study Group on Survival Training, sponsored by the Air Force Personnel and Training Research Center,” according to a classic paper West, Faber, and psychologist Harry Harlow published in the December 1957 issue of the journal Sociometry. The Director of the Officer Education Research Laboratory at Maxwell AFB, possibly Herman J. Sander (about whom more below), monitored the research project. The resulting paper was titled, “Brainwashing, Conditioning, and DDD (Debility, Dependency, and Dread).”

West and his associate wrote the “DDD” paper based on studies of military survival school subjects who had undergone mock torture camp experiences. The essay impressed the CIA so much, they made special mention of it in their 1963 manual on counterintelligence interrogation, the so-called KUBARK manual (p. 112-113), which included chapters on use of sensory deprivation, drugs, hypnosis, debility (or induced physical weakness, as through hunger), as well as use of threats and fear in interrogation. The DDD paper was “well worth reading,” the CIA gushed.

According to West’s 1956 GAP presentation, “Department of Defense teams debriefed all [235] airmen at the time they were returned.” The Air Force’s Office of Special Investigations conducted “detailed interviews” on the men, followed by “personal interviews… with a number of returnees” at the Officer Education Research Laboratory at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama.

According to a June 1956 HUMRRO monograph on U.S. Army POW collaboration with and indoctrination by the Chinese Communists, the Officer Education Research Laboratory released a July 1954 “Interim Report of Communist Exploitation of USAF POW [sic] in Korea.” The report was marked “SECRET.” Maxwell Air Base was, of course, also where the Air Force’s Human Resources Research Institute, with likely CIA input, ran Project Repair, the study of the returning Air Force flyers. The July interim report was most likely part of the Repair study.

According to West, many of the interviews of the returning airmen were “tape-recorded and observed through one-way screens.” Moreover, “the enemy had a considerable degree of success in obtaining intelligence information… the most persistent and important object appears to have been the attempt to make propaganda use of Air Force personnel primarily in connection with bacteriological warfare (BW) ‘confessions.’”

According to West’s figures, 83 captured airmen were interrogated about BW, and 36 gave “some sort of confession.” Of the 36, 23 Air Force POW confessions were used for propaganda purposes” (pp. 272-274). For West, whose presentation relied on the work of Albert Biderman (see below) for the elaboration of the kinds of stresses he believed allowed for the collaboration, the BW confessions were “false.”

Whether West believed that or not, his confidence in this regard is belied by his claim otherwise that the Communist interrogations were successful in “obtaining intelligence information.” Moreover, West believed that collaboration with enemy captors was not simply an either/or affair, but that no prisoner totally abstained from collaboration, and no collaborator fully accepted or worked with his captors without some resistance.

West’s CIA connections continued for some years. He left the Air Force in 1954 and became Chief Psychiatrist at the University of Oklahoma. From 1956 to 1966, he was a psychiatric consultant to the U.S. Air Force Hospital Force Base in Oklahoma. In 1966 he moved to California, where as psychiatric consultant at Palo Alto Veterans Administration Hospital and later the VA hospital in Los Angeles, he continued conducting research for the CIA. Much of this is described in O’Neill’s book and his The Intercept article.

As a coda on West, it is interesting to point out that he was appointed by the government to conduct a psychiatric assessment on Jack Ruby, the assassin of Lee Harvey Oswald. According to O’Neill, Ruby attorney Hubert W. Smith chose West because of West’s fame for his “studies of brainwashed American POWs.” Smith thought, “West could use his ‘highly qualified’ skills as a hypnotist and an administrator of the ‘truth serum, sodium pentothal’ to help Ruby regain his memory of the shooting”(O’Neill, Tom. Chaos (p. 378). Little, Brown and Company. Kindle Edition). West found that Ruby had suffered a psychotic break only shortly before West examined him. The court request for use of hypnosis and truth serum on Ruby made the pages of The New York Times.

Edgar Schein, Ph.D.

There were a number of other researchers suspected of CIA links who were involved in the study and treatment of the returning Air Force and Marine flyers who confessed to use of BW. Given the clandestine nature of intelligence work and affiliation, it is difficult to document how many in particular were working for the CIA. Some researchers accepted money from the CIA but were not necessarily CIA themselves.