“False” Confessions Cover-up: U.S. Told Airmen Who Admitted Germ War in Korea They Could Reveal Information If Captured

That US airmen confessed to dropping germ bombs in Korea has been attributed to Communist torture. Imagine my surprise to learn they were instructed to confess!

This article will explore the long-hidden fact that captured U.S. flyers, who stated under interrogation to their Chinese captors that the U.S. had undertaken a program of biological warfare (BW) in the Korean War, in fact had been told by their superiors that if captured they could tell interrogators whatever they felt they must. Some said they were even instructed to “tell all.”

No sooner were the controversial instructions on conduct under interrogation revealed during a high-profile military hearing in spring 1954 than the revelations from the hearing were classified and removed from public view.

The instructions to talk given to flyers prior to their capture differed significantly from those given to regular enlisted men, who were instructed they could only provide the standard name, rank, serial number and other simple demographic information to their enemy authorities. Airmen and regular troops differed considerably in age and educational status.

Even before the war was over, a cover story was concocted that the flyers who provided interrogators detailed depositions about the U.S. germ warfare program were subjected to extraordinary pressures, including Communist “brainwashing” and torture. This has been for decades the mainstream view of most press and academic accounts of the Cold War-era “germ warfare” controversy.

Recent examples of the false confession narrative include such disparate cases as Nicholson Baker’s interview with former prisoner-BW confessor who recanted, Air Force Lieutenant Floyd O’Neal, in Baker’s book, Baseless (pg. 292–295); and a 2021 Amici Curae filing (pg. 8) to the Supreme Court by Physicians for Human Rights and related medical professionals on behalf of U.S. torture victim Abu Zubaydah.

The most powerful evidence regarding the production of “false” biological warfare testimony came from the flyers themselves. Though only approximately eight written recantations were ever produced publicly (see PDF pgs. 44–84), all the flyers who confessed were said to have retracted their confessions after repatriation. Why would they do that if the confessions were not, indeed, coerced?

A recent article detailed in depth how returning prisoners of war involved in the U.S. military’s germ warfare program and operations were isolated from other prisoners after they were freed by the Communists. In short order, they recanted their BW confessions under threat of prosecution for treason.

At least one high-profile prisoner, Colonel Frank Schwable had his recantation statement edited (if not in part written) by the U.S. Army’s Counter-Intelligence Corps on board ship on his return to the United States. (There is more on Schwable later in this article.)

Some of the flyers may have been subjected to mind-control experiments consistent with the CIA’s Project Artichoke. On the other hand, some of the flyers may have been subjected to coercive pressures while in captivity in North Korea and China, especially use of solitary confinement. Even so, the fact that the flyers had permissive instructions about what to say if captured throws the entire “false” confession narrative into significant doubt.

The first campaign to discredit the germ warfare confessions

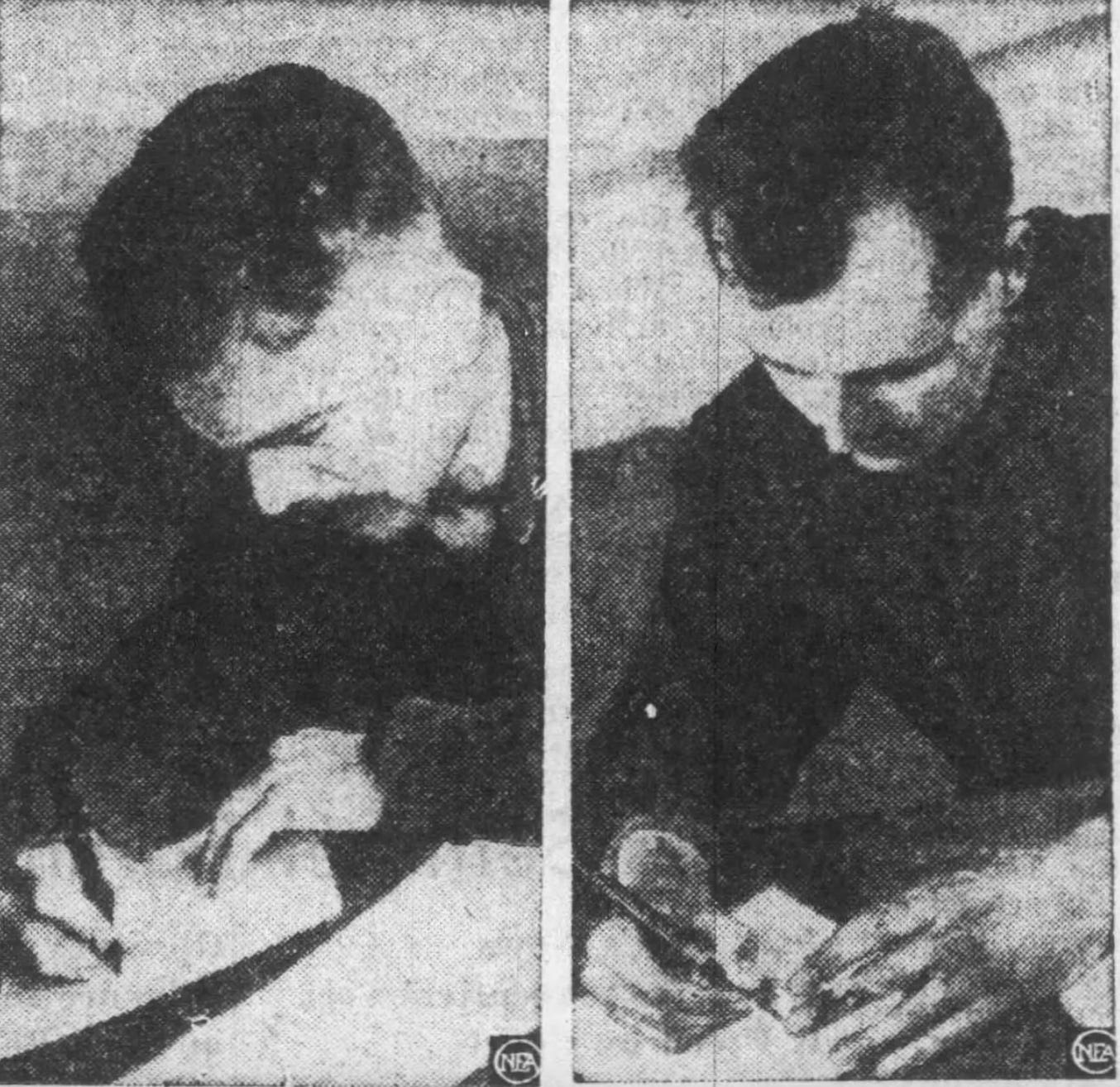

The battle over the veracity of Soviet, DPRK and PRC allegations of U.S. germ warfare was largely fought over the bodies and psyches of the men who confessed to knowledge of and participation in the U.S. biological weapons bombing of North Korea and China. The first accounts came from lower-level officers like Air Force navigator, Lt. Kenneth L. Enoch, and pilot, Lt. John Quinn.

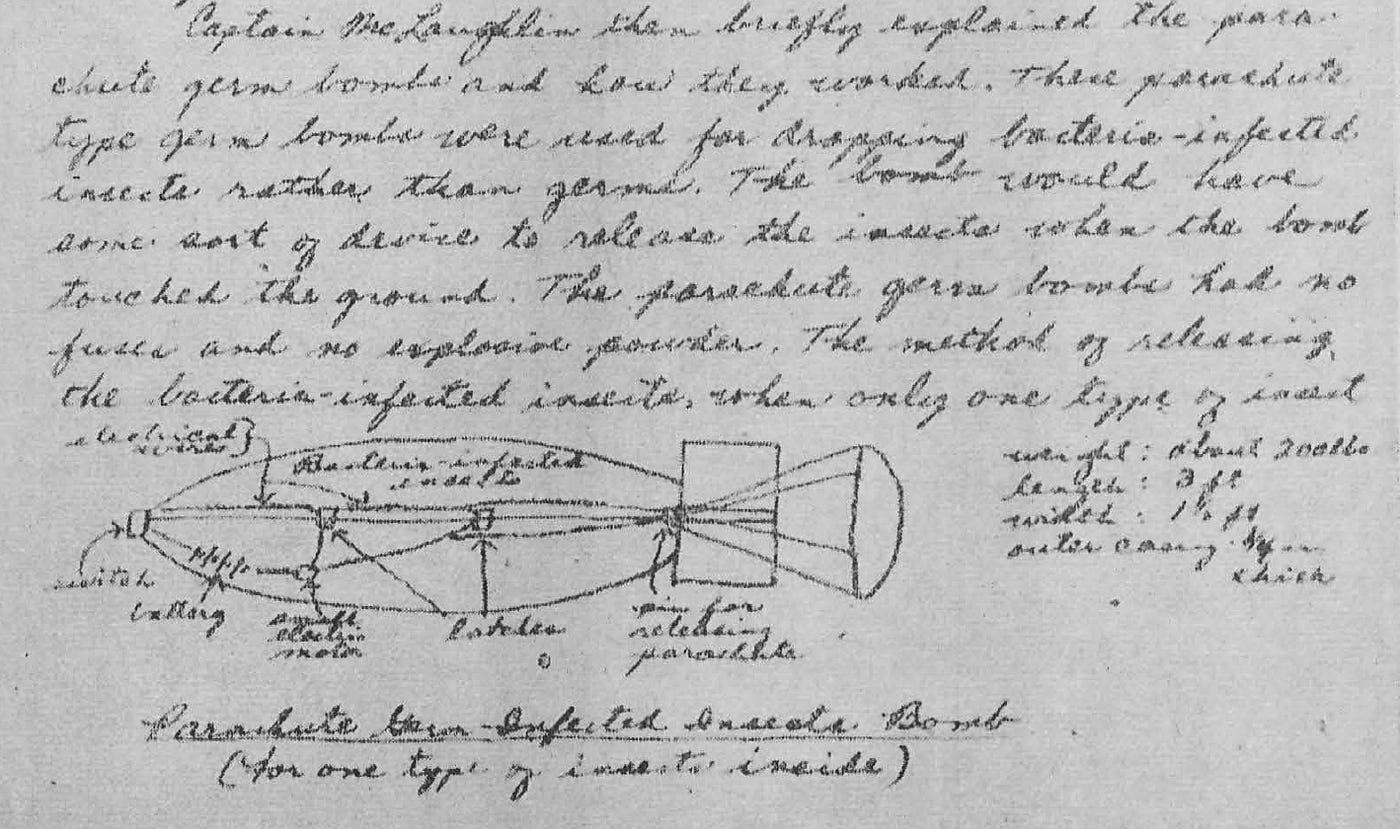

Enoch and Quinn’s written testimonies, along with similar statements by two other Air Force airmen, Lt. Floyd B. O’Neal and Lt. Paul Kniss, were published as appendices to the September 1952 report of the International Scientific Commission (ISC), an independent, ad hoc group assembled at the behest of the leftist World Peace Council and China’s Academia Sinica to assess the evidence gathered as to U.S. use of germ warfare.

The ISC report was a major counter to U.S. denials of use of biological warfare. The investigation was headed by famed British biologist Joseph Needham. A government plan to discredit both the report and Needham himself was centered in the Truman administration’s Psychological Strategy Board and the British “foreign office’s anti-communist propaganda wing, the Information Research Department [IRD]” (link, pg. 517).

These attempts to discredit Needham and the ISC report were only partially effective. According to a 2001 article by Tom Buchanan, IRD “attempts to induce the Medical Research Council and the London School of Tropical Medicine to issue a ‘public and systematic refutation of the [ISC] charges’ had been politely rebuffed” (p. 518). Pressures on the British Royal Society to condemn Needham were also unsuccessful.

On the other hand, IRD was more successful with officials at the United Nations Association, where Needham held office as vice president of its eastern region. IRD also successfully planted in the press articles critical of Needham and the germ warfare charges. The “diplomatic correspondent of the BBC was ‘specially briefed’” (p. 520).

“Collaboration in a manner which could be considered treasonable”

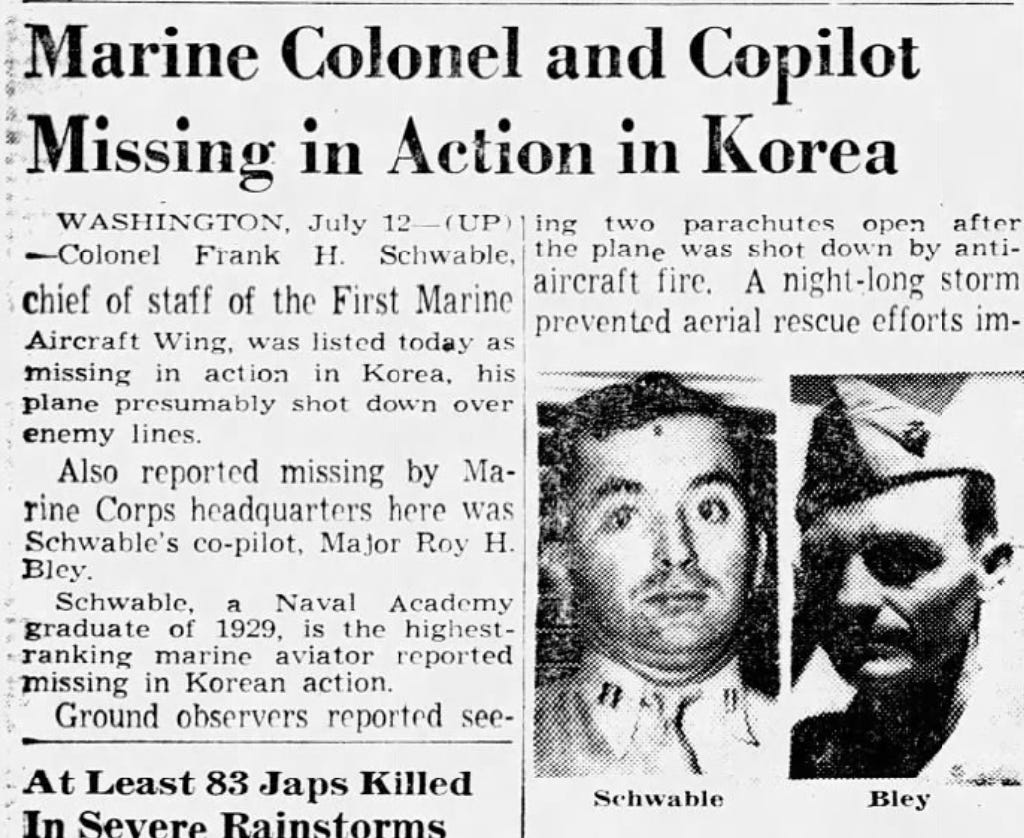

The first high-ranking prisoner — in fact, the second-highest ranking U.S. prisoner in the entire Korean War — to confess was Colonel Frank Schwable. Schwable had been Chief of Staff for the First Marine Air Wing in Korea. Four other colonels reported to him, including those responsible for intelligence (G-2), operations (G-3), and logistics (G-4). The Marine aviator’s downing made the papers back in the United States.

Schwable’s confession, broadcast by China on 22 February 1953, was the first by a high-ranking officer, and detailed the chain of command in ordering and implementing the BW orders. For more on Schwable’s confession, and that of the other higher-ranking officers, see the article, “Secret History: U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps Flyers’ Confessions on Use of Biological Weapons in the Korean War.”

Later, upon repatriation to the United States in September 1953, Schwable and fellow officers who had confessed to use of biological weapons, were isolated upon transport back to the U.S. On board the ship MSTS Howze, travelling to San Francisco, Schwable and the other confessing airmen were coached by Counter Intelligence Corps officials (and possibly other military or intelligence officers) in writing retractions of their confessions.

Lt. Col. Robert Matthews, who was chair of the Joint Intelligence Processing Board (JIPB) on the Howze, told independent historian Raymond Lech that he advised Schwable to write what he wanted, but “anything that he said or wrote could be used against him in a court-martial” (Tortured Into Fake Confession,pg. 147, quoted at link).

Matthews also told Lech that as senior officer he instructed other JIPB staff that “right from the beginning, each soldier or airman was to be warned, prior to interrogation, that he ‘was suspected of an offense that did involve collaboration in a manner which could be considered treasonable in that it rendered aid and comfort to the enemy’” (p. 148).

The threat was very effective and it led to a reported retraction of the BW charges by all who confessed. It also led to years of silence by the former airmen, with the exception of Kenneth Enoch. Enoch told Tim Tate and his Al Jazeera documentary crew in 2010 that while he denied being part of a germ warfare campaign by the U.S. Air Force, he also denied being tortured or maltreated by his Chinese captors. (Enoch’s statement to Tate can be viewed in Tate’s documentary at time stamp 37:27.)

Some Pentagon officers and other government officials were outraged by the confessions of Schwable and others. They wanted prosecutions of those former prisoners whom these officers and officials saw as traitors.

Writing about the Schwable-Marine Corps Board of Inquiry in The New York Times on 21 February 1954, journalist Elie Abel stated, “The Marine Corps with its Halls of Montezuma-Semper Fidelis tradition to protect and to instill in recruits, was stunned by the Schwable case. In the top command there were demands for swift, summary punishment.”

Other officials, presumably aware that any trial could potentially bring up extremely sensitive information about the U.S. biological warfare program, including use of such weapons in Korea, argued for leniency.

Indeed, the U.S. State Department/CIA/Department of Defense “Basic Plan for U.S. Action to Destroy and Counter-Exploit the Soviet Bacteriological Warfare Myth,” approved in October 1953, brought up this very subject:

Soviet methods of psychological coercion are capable of compromising most individuals whom they are determined to break…. The overall propaganda objectives of the U.S. action set forth here are best served by the avoidance of punishment of military or civilian personnel who have been so exploited by the Soviet bacteriological warfare propaganda campaign.

Furthermore, the plan stated, “If the risk of adverse propaganda effect cannot be avoided in cases of clear necessity for disciplinary or penal action, the employment of public or publicly known investigations and proceedings should be kept to the minimum required under law” (p. 8).

In other words, the public was not to know much about any of this. The reader might reflect upon just how effective the suppression of the facts revealed at the Schwable inquiry turned out to be.

The Board of Inquiry

In February 1954, Col. Schwable was brought before a Marine Corps initiated Board of Inquiry, the only officer who confessed to publicly be brought before any kind of official examining body. While some of the testimony was delivered in secret, the inquiry was otherwise open to the public and reported on in newspapers at the time.

There is one notable important example of the occasional resort to secrecy that surfaced during the board of inquiry hearings. Col. Schwable had insisted that though he reached out to the Defense Department after his repatriation for “policy guidance” on how to respond to press inquiries about his POW experiences and his confession, no such official guidance was offered.

But the Defense Department did respond to Schwable’s request, but what they told him was, and apparently remains, classified. According to a report by Sam Stavisky in the 26 February 1954 Washington Post, the Pentagon gave no substantive reply to the request for guidance. The Post report added, “Just what the Pentagon did say in its radioed reply was a military secret, the Court [sic] of Inquiry ruled in clearing the hearing room of press and public.”

Oddly, other contemporaneous press accounts of Schwable’s “policy guidance” request, such as reported by Associated Press and United Press, did not indicate there was anything secret about the Defense Department’s reply to Schwable’s request, only that there had been no reply, or that “no such guidance was forthcoming.” AP added that even full details of Schwable’s request were kept secret when the hearing went into classified session.

The question of what the Pentagon did say to Schwable at the time is of high importance when judging whether or not the retraction of his BW claims was coerced or not.

Meanwhile, during the Board of Inquiry, expert testimony from intelligence-linked psychiatrists, and even non-psychiatric “experts,” were a highlight of the hearings. These “experts,” who were called by the defense, found that Schwable had succumbed to intense pressures, which one expert, Joost Meerloo, labeled “menticide.”

One of those who testified on behalf of Col. Schwable was Winfred Overholser, MD, director of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for the Mentally Ill in Washington D.C. Dr. Overholser had important experience in intelligence matters. During World War II, he led a secret joint project of the Office of Strategic Services (forerunner to the CIA) and the National Defense Research Council studying the effects of various “truth drugs.”

The findings and recommendations of the Schwable board of inquiry merited a full page in the New York Times, which published them all on 28 April 1954. (It appears the material originated with Associated Press.) Some of the findings were redacted, particularly those that bore upon what instructions flyers had received about what they could say if captured and interrogated.

The Board of Inquiry — three Marine Corps generals and a Navy admiral reporting to the Commandant of the Marine Corps — determined, “That the statement and tape recording of Colonel Schwable relative to the waging of bacteriological warfare in North Korea occurred as the result of mental torture of such severity and compelling nature as constituted reasonable justification for entering into such acts.”

Schwable was said to have “resisted this torture to the limit of his ability to resist.” But his capitulation was still shameful, having “given aid and comfort to the enemy.”

As a side note, unacknowledged by anyone at the time, and unnoticed, it seems, by later historians, one member of the inquiry board, Major General Christian F. Schilt, commanding general for the First Marine Air Wing in Korea, until he left that position on April 12, 1952, was mentioned by Schwable in his “confession” as being involved in giving orders to his unit to participate in the germ warfare campaign. Schilt should have recused himself. Moreover, it is strange that Lech’s history of the Schwable trial never mentions this conflict of interest on the inquiry panel.

In its concluding “Statement of Facts,” the inquiry board cited Article 1223, U.S. Navy regulations, and Section 0919 of the U.S. Navy Security Manual for 1951, to the effect that POWs were “prohibited… from disclosing to the enemy any information other than name, rank, serial number, home address and place and date of birth.”

But, missed by most historians, there were five censored paragraphs (out of 61 total in the “Statement of Facts”), each apparently having to do with “differences in the instructions authorized to be given military personnel having reference to the conduct of prisoners of war.”

Paragraph 8 in particular was redacted because it contained classified material, including “certain procedures… authorized by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff through the service chiefs having reference to conduct of prisoners of war.”

There was yet another sixth redacted paragraph, which was in the Opinion section of the Board of Inquiry release. Paragraph 11 was “deleted because it contain[ed], in part, classified information… relat[ing] to differences in instructions regarding information which may be revealed by a prisoner of war.”

Thanks to the description of what was deleted, we know then that there were differences in the instructions given to captured air personnel that were not consistent with U.S. military regulations. What were such differences, and why did they exist?

Conflicting instructions

General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., Commandant of the Marine Corps, issued his own separate opinion in the Schwable case, released along with the findings and opinions of the inquiry board. Shepherd indicated that indeed there were conflicting instructions given to Schwable and other airmen about what their behavior should be if captured by the enemy.

“The preoccupation of the Court with respect to the adequacy of Colonel Schwable’s briefing and the conflicting nature of existing instructions relative to the conduct of members of the armed forces while held as prisoners of war by the enemy have been noted,” General Shepherd wrote.

Nevertheless, “Colonel Schwable… was aware of the nature and quality of his acts and of their severe effect. In his case there was no real requirement for detailed elementary guidance of the type which the court found to be lacking.”

By “elementary guidance,” Shepherd was referring to instructions to military personnel about what information could be provided to the enemy if captured.

There were other accounts of what could be called the instructions controversy in the press during the course of the inquiry itself.

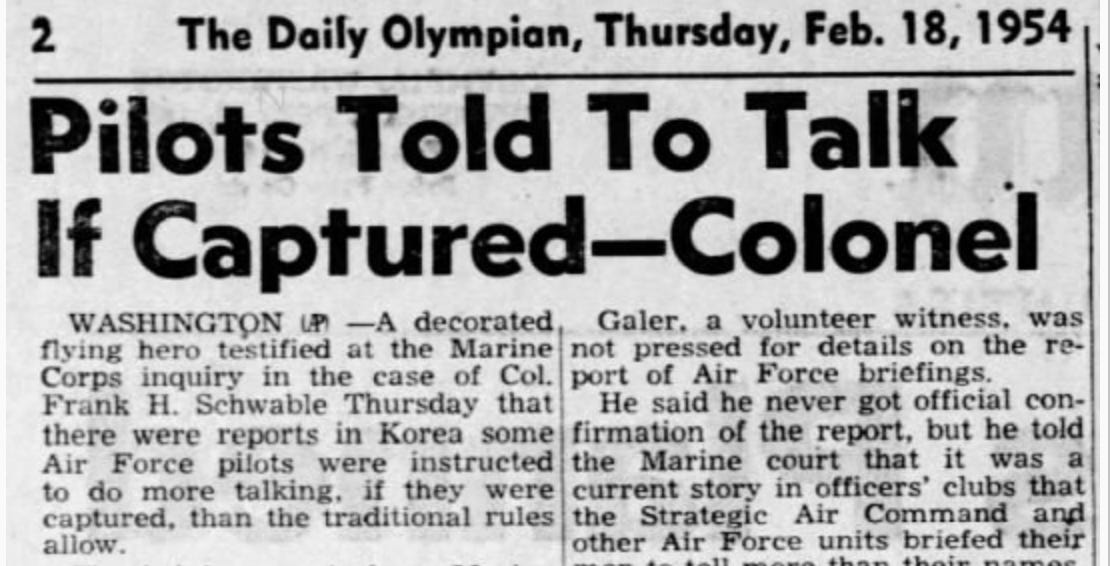

An Associated Press 18 February 1954 article cited a decorated Marine Corps aviator who was also shot down in the Korean War, Colonel R.E. Galer.

Galer told the Board of Inquiry “that it was a current story in officers’ clubs that the Strategic Air Command and other Air Force units briefed their men to tell more than their names, rank and serial numbers.”

The AP story also provided Air Force denials of such instructions. The article quoted Air Force Chief of Staff, Gen. Nathan Twining, who told a Pentagon news conference the Air Force never ordered pilots to tell their captors more than “the bare facts of their personal identity.”

Twining was the author of a controversial memo in October 1950, nearly four months into the Korean War, which initiated a crash program in the development of biological weapons.

According to Nicholson Baker in his recent book, Baseless, on the history of U.S. biological warfare during the Cold War, Twining’s top secret directive stated, “‘The Joint Chiefs of Staff have agreed that action should be initiated at once to make the United States capable of employing toxic chemical and biological agents and of defending against enemy use of these agents.’ Twining ordered his deputy chief of staff for operations, Thomas D. ‘Tommy’ White, to ‘Integrate the Air Force capabilities and requirements for Biological and Chemical Warfare into existing and future War Plans.’ And also to ‘Develop appropriate tactics and techniques for aerial delivery.’” (p. 170).

In October 1953, four months after the Korean War armistice, Twining’s directive was rescinded.

“Go ahead and tell the truth, gentlemen.”

The testimony before Schwable’s inquiry board about the controversial interrogation instuctions continued. On 24 February 1954, Major Walter R. Harris, a decorated Marine aviator and former Korean War POW, who had organized resistance in his POW camp, told the Schwable inquiry panel that before they were deployed, as regards capture, “75 to 80 per cent of the air personnel” in his camp “had been instructed to tell anything you want to.” Another “15-20 percent were told to use their own discretion,” Harris testified.

According to United Press’ reporting, Harris said his briefing officer at El Toro Marine Base had told him prior to shipping out to Korea that the old code, whereby a prisoner only provided name, rank and serial number, “is out.”

“‘They are going to find out the truth anyhow,’ Harris quoted the briefing officer. ‘Go ahead and tell the truth, gentlemen. It can’t hurt us. You don’t know anything.’”

Not knowing “anything” may have been true for the majority of pilots, navigators and gunnery officers captured, but not for top officers like Schwable and Mahurin, who provided copious details about the chain of command and top secret operations.

By the end of the judicial proceding against Schwable, the controversial instructions about what to tell their captors was common knowledge. As reported in a 28 April 1954 UP story, “Testimony in the Schwable case indicated the Fifth Air Force, under which his Marine air wing was operating, had authorized prisoners to impart more information than mere identity.”

The issue was also highlighted in newspaper editorials following the Schwable verdict.

A 2 May editorial in the Louisville Courier-Journal endorsed the panel’s recommendation that the Defense Department “promulgate binding instructions to all services on the conduct of United States military personnel who may become prisoners of war.” The recommendation to issue such binding instructions led to the adoption of a military “Code of Conduct” that reiterated the promulagation of the old name, rank and serial number rule thoughout all the military services.

The failure to have a consistent rule of conduct was highlighted in the Schwable case, where, as The Courier-Journal pointed out, “instructions to personnel of the Fifth Air Force, to which Colonel Schwable’s First Marine Wing was attached, differed considerably from the Army and Marine Corps’ traditional reliance on the Geneva Convention provision that no prisoner tell his captors more than his name, rank, serial number, home address and place and date of birth.”

“A delicate problem”

The instructions for airmen may have been behind the findings of a 1997 Associated Press investigation, which determined that, according to archives released after the fall of the Soviet Union, during the Korean War many captured U.S. airmen provided a good amount of information to their Chinese and North Korean captors, much of which filtered through to Soviet intelligence.

According to AP: “Some American airmen who fell into communist hands after being shot down over North Korea and China resisted cooperating with their interrogators. Others provided reams of military data as well as personal observations on morale in the U.S. ranks. Some said they saw little sense in the war.”

The fact that many, if not most, U.S. POWs in the Korean War provided information to their captors beyond name, rank and serial number was buried in a 1955 Department of Defense report by the Secretary of Defense’s Advisory Committee on Prisoners of War. “[N]early every prisoner in Korea divulged something,” the report stated.

The report endorsed the policy of a strict code of conduct for all prisoners. Nowhere in the report is there any mention of conflicting instructions to Air Force and Marine airmen during the Korean War on what information to give their captors if shot down. Perhaps it was mentioned in the report’s one page appendix on “Code of Conduct,” but that page (pg. 40) is entirely redacted in available versions of the report.

The only seeming adversion to the controversy over differing instructions in the POW report is this piece of bureaucratic gobbledy-gook from the introduction by the Defense Advisory Committee:

We examined the publicly alleged divergent action taken by the Services toward prisoners repatriated from Korea. The disposition of all cases was governed by the facts and circumstances surrounding each case, and was as consistent, equitable and uniform as could be achieved by any two boards or courts. As legal steps, including appeals, are completed and in light of the uniqueness of the Korean War and the particular conditions surrounding American prisoners of war, the appropriate Service Secretaries should make thorough reviews of all punishments awarded. This continuing review should make certain that any excessive sentences, if found to exist, are carefully considered and mitigated. This review should also take into account a comparison with sentences meted out to other prisoners for similar offenses. (pp. vi-vii, bold added for emphasis)

The Committee added, “In concluding, the Committee unanimously agreed that Americans require a unified and purposeful standard of conduct for our prisoners of war backed up by a first class training program” (p. vii). The training program would later become the military’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape training, known as SERE. SERE’s mock torture training component was observed by CIA and Department of Defense researchers, was integrated into the CIA’s own interrogation manual, and nearly four decades later, after 9/11, was used as the basis for the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” torture program.

The Schwable Board of Inquiry was not the only military review of POW acts of collaboration or confessions. The Air Force held non-public hearings on 83 officers and airmen who had been captured. None of the confessing Air Force prisoners was disciplined.

An article in the June 1954 edition of Air Force magazine, “POWs: What Do We Owe Them?”, praised the way the Air Force “handled a delicate problem honorably and equitably.”

The article quoted a November 1953 Air Force editorial by General George C. Kenney, who was also the president of the Air Force Association, which put out Air Force magazine, to the effect that “our airmen in Korea were not adequately trained in psychological warfare.”

Kenney reiterated the government’s position that the germ warfare charges were “ludicrous” and the confessions themselves the result of “ingenious methods of mental torture and, in some cases, brutal physical torture.”

But the June Air Force article also reported the findings of the Air Force board, which had been publicly released a month earlier. The Air Force board had found that “the briefing and indoctrination given our combat personnel as to conduct of prisoners of war was inadequate and confusing. Published policy and directives in the regard are given mixed interpretations at various command levels.”

The memory of the flap over the mixed intructions to flyers regarding their possible response to interrogation had dissipated a great deal. Certainly it was deemphasized within months. As stated above, the issue was not even mentioned in the release of a DoD Advisory Committee report on the Code of Conduct. By May 1956, an 86-page article in the Columbia Law Review, “Misconduct in the Prison Camp: A Survey of the Law and an Analysis of the Korean Cases,” only alluded to the issue in one solitary footnote (pg. 775 [pg. 67 PDF]).

There was one final important corroboration to the tale of conflicting interrogation instructions. That came from famous World War II flying ace, Air Force Colonel Walker Mahurin, who was also shot down over North Korea. Like Schwable, Mahurin also gave a damaging deposition to his Chinese captors about U.S. use of biological weapons, and later wrote a 1962 book about his experiences, Honest John.

Mahurin wrote critically about his training regarding what to say if captured:

I recalled that our briefings had never been specific when it came to what to do if captured. Sometimes it was said: “Give your name, rank and serial number only.” Other times: “We can’t tell you what to do or say.” Still other times the instructions were: “Tell them anything they want to know.” If you were fresh out of Kendallville, Indiana, with a year or so of college, and received these conflicting instructions, would you know what to do?

(quote above is from Mahurin, Colonel Walker M., Honest John, Tannenberg Publishing. Kindle Edition. Location 4416 out of 4872)

It’s evident the existing narrative about the Korean War and the controversy over POW confessions to use of germ warfare are seriously distorted by decades of misinformation and censorship. This malpractice of the historical method has seriously undermined our understanding of what really happened during the Korean War.

Because of the animus towards North Korea, and increasingly, China, in the United States, whipped up by a hostile government and a jingoistic press, there is little appetite to set the story straight. It’s my hope that this essay is a step in the right direction, away from war, and towards greater understanding between the countries involved.

Postscript

Normally I don’t add such postscripts, but I must admit that when I initially drafted this article, I believed that the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s instructions discussed above to the Korean War-era pilots, including those airmen dropping biological or bacteriological bombs on North Korean and China, were unique. It seemed as if the directions — to by-pass the Geneva-based maintenance of a “name, rank and serial number” restriction on information that could be provided to one’s captors — was essentially a one-off.

But I was reading the autobiography of Soviet double-agent George Blake the other day. Blake related how during World War 2, Britain’s Special Operations Executive, in charge of UK-backed covert partisan warfare in Nazi-occupied Europe, instructed its agents to reveal, if necessary, certain amounts of critical operational details if captured. The idea was that the Gestapo used torture, which very few could withstand, and that it was better to protect one’s agents from torture or death, than try to maintain secrets the Nazis were bound to get anyway.

This was not unlike the rationale the U.S. used in allowing its flyers the right to reveal details of the BW operations, though the question of whether or not the North Koreans or Chinese used torture is more controversial than the generally recognized fact that the Gestapo did. Nevertheless, the rigors of confinement in a POW camp and even intense interrogation short of torture, along with use of solitary confinement, was, Pentagon authorities knew, likely to cause some airmen to break down and provide information. Hence the policy described in this article.

For more information, see Blake’s book, No Other Choice (Simon & Schuster, 1990, pp. 92–93, hardback edition). Also this Twitter thread, which discusses another historical instance, this time from World War Two, where combatants were instructed to reveal information if captured, in the belief it would rescue them from potential torture.

This article originally appeared at Medium.com on 31 August 2021. It has been very lightly edited in this reprint, including the addition of a new photo, that of Enoch and Quinn signing their confessions.