Forgotten Scandal: Canadian Peace Congress Leader Threatened for Leaking Canada’s Cooperation with U.S. Germ Warfare

Canada had a more central role in the U.S. biological warfare effort than is generally known. When ex-OSS agent, Rev. James Endicott, suggested Canadian work on insect vectors, he was wrongly vilified

This article has been slightly modified from its original appearance (under a different title) in The Canada Files, March 14, 2023. New documentation on Canada’s Cold War experiments breeding insects and rodents for use in biological warfare has been added to this article.

It was late April 1952 and the Korean War was nearing its second anniversary with no end in sight. In Canada, newspapers and the Canadian government erupted in fury when it was reported that the Canadian Peace Congress’ chairman implied that Canada may have supplied infected insects to U.S. forces, who were accused of bombing the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea (DPRK) and China with bacteriological or “germ” weapons.

China and the DPRK (also referred to as North Korea) accused the United States, under the umbrella of United Nations intervention, of using fleas, flies and other insects that had been deliberately infected with plague, cholera, anthrax and other diseases, to deliver deadly pathogens to Communist troops and civilians.

The charges have long been considered a controversy with perhaps no definitive solution. In 2010, secret Korean War CIA communications intelligence reports were declassified, which described radio intercepts of Chinese and DPRK military units reacting to the biowarfare attacks. These reports have established that a preponderance of the evidence supports the fact the U.S. did engage in biological warfare during the Korean War.

The story regarding possible Canadian involvement in the germ war campaign was broken in a British United Press (BUP) dispatch on 14 April 1952. BUP reported that James G. Endicott, “chairman of the communist-backed Canadian Peace Congress,” claimed he had “‘fully proved’ Communist charges that the Allies are using germ warfare and believes the bacteria may have been produced in Canada.”

The Canadian Press news agency carried a rather larger account the next day. As published on page one of the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, a Moscow radio broadcast monitored in London said Endicott, who had been speaking at a press conference in Mukden (Shenyang), China, had “speculated on the possibility that some of the ‘infected insects’ allegedly dropped in northeast China were bred in Canada.”

Endicott was also quoted “as saying Canada has organizations producing bacteriological weapons for the U.S., including a ‘huge plant’ in Alberta.”

The CPC chairman, the Reverend Dr. James G. Endicott, was not an unknown figure, nor was he politically naive. He was a famous churchman who spent over two decades as a missionary in China, and was a leader of Canada’s United Christian Church. Endicott was well-known inside Ottawa’s government hallways. In the 1940s he had been an adviser to Soong Mei-ling, aka Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, and China’s New Life Movement; a correspondent of government insider Lester Pearson; and during the final years of World War II, a secret OSS agent, code-name “Hialeah.”

Endicott had tried to convince Chiang Kai-Shek, unsuccessfully, of the importance of implementing land reform. Reporting back to the OSS on Chinese leaders in both the Kuomintang and Communist Party, Endicott found himself more and more drawn to the sincerity and popularity of the Communists, and he came to feel they offered the best hope for the Chinese people.

Endicott and the CPC had incurred the disfavor of many Canadian politicians by opposing the Korean War, and speaking out against the atrocities being committed by U.S. and allied forces there. Canada was part of the United Nations forces involved in the war.

Even before the Korean War, Endicott’s opposition to increasing Cold War government repression had attracted attention. In January 1949, multiple speaking engagements for Endicott in Vancouver were cancelled for overt political reasons.

At a September 1949 “Partisans of Peace” conference in Mexico City, he charged the United States “with organizing in Canada a wide network of spies who are watching the life of the Canadian population.” There followed calls in the press to arrest him as a "traitor to the Motherland." The notoriety led to Endicott being banned along with other peace activists from entering the United States.

However, Endicott’s charges about “spies” were not far off. Testimony in the U.S. Congress in January 1950 revealed the RCMP had been keeping files on thousands of “subversives,” which the U.S. used to impede entry into the United States, though Canadian officials denied it. With the controversy over Endicott’s purported statements about Canada’s involvement in the U.S. germ war in China and Korea, Canadian Justice Minister Stuart Gerson publicly told the House of Commons that “’such men’ as Canada’s Dr. James Endicott are kept under constant surveillance by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.”

With Endicott’s latest charges about possible Canadian involvement in the “germ war,” there was renewed agitation in the press and in Parliament to charge the Canadian Peace Congress leader with treason.

External Affairs Minister Lester Pearson told the press that the Communists’ charges of a U.S. germ war were a “clumsy hoax.” Anyone who would believe such stories were no better, Pearson averred, than “bait on a Red hook”! Pearson indicated the government was investigating if Endicott had broken any laws.

In the end, Endicott was not charged with anything. It may have been that Canada was not interested in a trial, where secrets surrounding Canada’s biological weapons program might be exposed. As it was, O.M. Solandt, chief of the Defence Research Board (DRB), which had responsibility for Canada’s biological warfare program, had already gone on the record in October 1950 that Canada’s military was doing far-flung research on biological warfare, including “defence” against insects. According to Solandt, a portion of Canada’s biological research that was conducted at Fort Churchill was “so secret… it can’t be discussed.”

A 2015 article by Matthew Wiseman for the journal Canadian Military History, described the Canadian Army’s Fort Churchill research facility:

“Located on the west bank of Hudson Bay in Manitoba’s northeast corner, Fort Churchill’s location, terrain, and harsh winter weather made it an ideal environmental locale for northern military training and scientific defence research.”

The isolated site was also the location of the Canadian Winter Warfare School. According to a 2014 article about the history of Fort Churchill, during or just after World War Two, the U.S. Army Air Force built a military base nearby capable of landing large B-52 bombers.

In author Nicholson Baker’s 2020 book about the U.S. biological warfare program, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act, Baker reported that Churchill was the site of “Canada’s Defence Research Northern Laboratory, which did cold-weather weapons testing.” The area had been used by Chemical Corps researchers since 1946 and was the site of a U.S. test release of radioactive mosquitoes in 1949. That same year, suspicions fell upon the site after a number of Inuit succumbed to a mysterious illness. (See Baker, pp. 214-215.)

Quite famously, the first reports of U.S. germ warfare in 1952 came during the dead of the Korean and Manchurian winter. Critics pointed to pictures the Communists released of insects wiggling on mounds of snow. They made much of the fact that it seemed absurd to think insects could be used as weapons in such a harsh climate.

Was the secret work at Fort Churchill related to experiments with insect cold-hardiness or perhaps the breeding of more cold resistant insects and bacteria to be used in germ warfare during the Korean War? It seems likely, especially when one takes into account Canadian (and U.S.?) interest in exploring possible BW insect vectors existing in more northerly latitudes, as discussed more fully below.

Entomology laboratories in Canada and elsewhere already routinely used selective breeding or artificial selection to produce insecticide-resistant insects. The cold hardiness characteristics of insects were also extensively studied. Canadian military researchers were already using selective breeding to increase the virulence of bacterial pathogens.

Biological warfare researchers in the West, as well as in Japan, were interested in how their bioweapons would work in wintry conditions. This was important as from the standpoint of these countries, the Soviet Union, with its vast tracts of frigid countryside, was thought of as their most likely target.

Shiro Ishii, the leader of Unit 731, Japan’s World War Two biological warfare unit, was, according to General MacArthur’s office in postwar Tokyo, an expert on “the use of BW in cold climates.” Ishii’s specialty was use of insect vectors in biological bombs. This specialty was used by MacArthur and scientists from the U.S. Army Chemical Corps at Camp Detrick, to help validate the usefulness of Ishii and his associates to military and political leaders back in Washington D.C. The latter were considering a bargain to provide amnesty for war crimes to Japanese bio-researchers, in trade for what they had discovered in their very active germ warfare program.

Along similar lines, a U.S. Chemical Corps report on its research and development division in autumn 1951 specifically mentioned work on “cold weather agents.” Hence, it’s not much of a stretch to imagine Canada’s own scientists assisting with this issue.

Supplying infected insects

In his book, Six-Legged Insects: Using Insects as Weapons of War, entomologist Jeffrey A. Lockwood wrote about the collaboration between Canada’s biological warfare researchers and their U.S. compatriots at Camp Detrick. “Although Camp Detrick's upper echelon was partial to airborne dissemination of pathogens, the Canadians' progress with rearing and disseminating insect vectors could not be dismissed. Entomologists from the two countries collaborated on a series of field experiments ranging from the banal to the bizarre,” Lockwood wrote. (Lockwood, Kindle Edition, Location 2778.)

For his part, faced with strong public criticism from Canadian politicians and editorial writers, not to mention possible prosecution, Dr. Endicott denied having accused Canada of any cooperation with the United States in biological warfare attacks against China or the DPRK. But, Endicott reiterated his belief in the veracity of China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s charges regarding U.S. use of biological weapons. His conviction stemmed from a recent trip to northeast China, where he visited alleged germ war attack sites, and interviewed Chinese scientists, as well as peasant witnesses to the infected insects and feather bomb attacks.

But were the charges of Canada supplying the U.S. with infected insects really false? After the Korean War armistice, an October 1955 article in the Calgary Herald profiled the Canadian military’s Suffield Experimental Station in Alberta. “A vast family of insects are reared at Suffield for use in experiments,” the article stated.

Both declassified records and oral histories have been used in recent years to document the fact that Canada was in league with the United States biological warfare program. Endicott, knowing he was walking on thin legal ice – the Canadian government had recently passed a draconian law against anyone speaking out against allied forces fighting in the Korean War – may have pulled his punches to stay out of prison.

The new law stated that a Canadian citizen could be prosecuted for “assisting, while in or out of Canada, any enemy at war with Canada or any armed forces against whom Canadian forces are engaged in hostilities whether or not a state of war exists between Canada and the country whose forces they are [fighting].”

Endicott, and the press interviewing him in Mukden, had hit a very sensitive topic. Canada had secretly provided major resources for use by the U.S. and British biological warfare programs. As recently as August 1945, Canada had been a secret supplier of infected insects to U.S. scientists exploring their use in offensive bioweapons. Even more, Canada had developed a special expertise in use of insect vectors to deliver infectious agents in warfare, an expertise that was unique to the field. Only Japan’s infamous Unit 731 had explored use of insects to deliver plague, encephalitis, cholera and other diseases to the degree that Canada had.

Today, Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC), a branch of the Department of National Defence and successor to the DRB, still operates its vast Suffield Research Centre (SRC) in Alberta. In 2003 the U.S. national security journal, Homeland Defense Journal, called the SRC “one of the most effective and innovative research and training centers on chemical and biological warfare in the Western world.”

According to Canada’s 2022 submission to the UN Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) review conference regarding “confidence building measures” relevant to adherence to the Biological Weapons and Toxin Convention, Canada’s Biological Defence Program at DRDC spent “approximately $3,365,269 CAD.” Another $4 million was spent on contracts with “external entities” in industry and universities.

Canada’s BWC document states, “No offensive [BW] studies of any kind are permitted by the Government of Canada.” But it notes that military research does continue on “the mode of action and toxicity of toxins and the mode of action and infectivity of biological agents,” supposedly exclusively for defensive purposes. But the Canadian government has made such claims historically before, and has been proven to have lied.

This article will look at:

Canada’s biological warfare program,

How it developed in conjunction with both the U.S. and the United Kingdom’s own BW programs,

Whether or not Canada supplied the U.S. with insects for use in the latter’s large biological weapons field test program and later full-scale germ warfare operations during the final eighteen months of the Korean War.

Reports from Japan, Fear of Germany

At the very onset of World War Two, some Canadian scientists were advocating for use of biological weaponry. Everitt G.D. Murray, a Professor of Bacteriology and Immunology at McGill University, wrote to famous Canadian scientist Sir Frederick Banting that he favored the use of insects to distribute disease organisms. Banting had won the Nobel Prize in 1923 for his co-discovery of insulin, and now he was consulting with the National Research Council on the feasibility of bacteriological warfare.

Scientists and military officials in Canada were concerned that Italy and Germany would use chemical weapons in the new, then-unfolding world war, as they had, along with Canada and its allies, in World War One. This fear extended to the use of “germ” weapons as well, following reports of Germany’s use of anthrax and glanders in World War One.

Murray was prescient in advocating for the use of insects to deliver a pathogenic payload. According to the account described in John Bryden’s 1989 book, Deadly Allies: Canada’s Secret War, 1937-1947, Murray told Banting that lice, fleas, mosquitos and ticks could deliver disease to the enemy. He also foretold the use of rats infected with plague that could be dumped on the enemy as well.

In Bryden’s account, Murray suggested both insects and rats could be dropped using “break-apart containers dropped from aircraft or contaminated letters sent through the mail” (pg. 55). Perhaps not coincidentally, much later, during the Korean War, international investigators would determine (see report pg. 27) that the U.S. dropped plague-infected voles (a small field rodent) on the Manchurian village of Kan-Nan in April 1952 using self-destructive containers.

It’s not clear how early Murray was reading reports of Japan’s own biological warfare attacks on China, which utilized a number of specially designed biological bombs, including fragile glass or porcelain bombs, as well as some with parachutes similar to what Murray described. The extent of Japan’s deadly research on human subjects, including thousands of fatal experiments, was not known to U.S. scientists (and likely Canadian and British scientists as well) until a few years after the war.

But as Bryden’s research confirmed, by 1942 Murray’s work was referencing Japan’s Unit 731 research, as he followed reports of Japan’s use of fleas and other materials carrying bubonic plague.

Indeed in a Boston Globe article on 27 February 1942, journalist Fletcher Pratt wrote, “In December, just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese planes appeared over Chinjua, Chin and Chiu, in Chekiang Province... trailing behind them what appeared to be white fumes... [which] proved to be living fleas, infected with cultures of bubonic [sic] and typhus, and fish eggs with the same."

At the same time, Canadian researchers working for Canada’s top secret M-1000 Committee were being recruited to bring Canada’s extensive field testing apparatus and expertise for the purpose of assisting England in its crash program to develop a biological bomb using anthrax as agent fill. The U.S. would be brought on board as well, and a pilot plant to produce anthrax was set up at the U.S. biological warfare research facility at Camp Detrick, Maryland. Work on a more commercial plant began in Vigo, Indiana, but didn’t reach full status because the war ended before it could become operational.

The insect laboratory

The anthrax project didn’t mean the insect vector idea was abandoned, however. In August 1942, prominent bacteriologist and medical researcher at Queen’s University (Kingston, Ontario), Professor Guilford Reed asked Murray, now chief of the M-1000 Committee, to hire an entomologist. Reed wanted to establish a flea breeding colony at his biological lab at Queen’s, with the intention of developing a way to combine plague bacteria with flea-borne typhus as an offensive weapon. (See Bryden, pg. 111.)

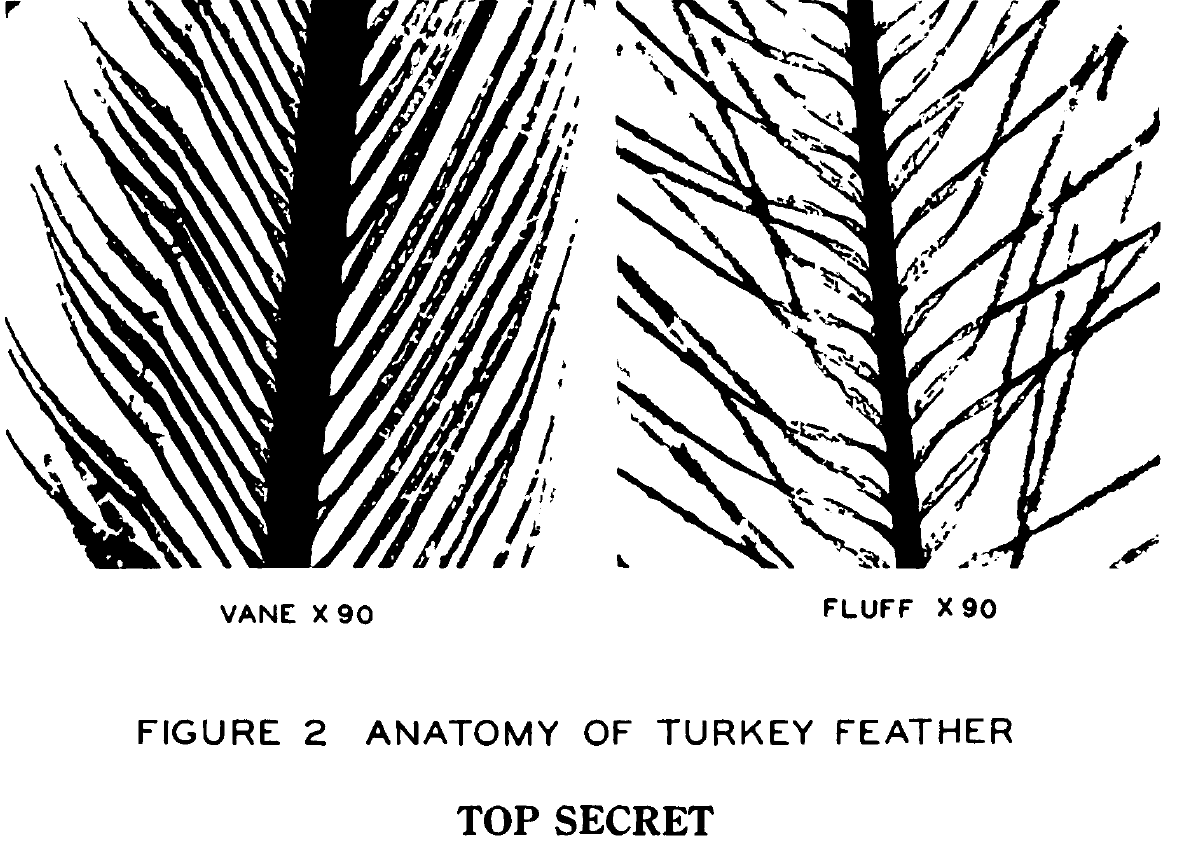

Reed’s insect laboratory in Kingston was, as Bryden put it, “a Canadian innovation,” where there was a “special media” unit for infecting insects with deadly pathogens. During these dark days of world war, Reed concentrated on experiments with house flies, fruit flies, fleas and ticks. There were special projects to produce toxins from botulinum and gas gangrene bacteria, as well as experiments to increase the virulence of various types of germs via use of selective breeding. (Critics of today’s “gain-of-function” biological experiments may be surprised to know that attempts to produce more deadly pathogens in the laboratory go back many decades.)

According to Bryden, up until 1944, Canada alone of the Western allies was working on insect vector biological weapons. Reed had farmed out the breeding of the insects to Dominion Parasite Laboratory in Belleville, Ontario (Dominion was a site that researched “biological control” of insects). The bugs were then fed and infected with bacteria at Reed’s lab in Kingston, and further shipped to the Suffield experimental proving grounds in Alberta.

Opened in 1941, the Suffield complex extended over 2600 square kilometers (1000 square miles). This was likely the “huge plant” in Alberta Endicott was referring to in his April 1952 Mukden press conference.

In November 1944, Reed met with officials from the U.S. Chemical Corps’ Special Projects Division (SPD). The Chemical Corps, a division of the U.S. Army, had been given responsibility for the development of the U.S. biological weapons program. In doing so, it worked closely with the U.S. Air Force, including its Air Materiel and Strategic Air commands, the Navy, and the Central Intelligence Agency.

Reed told SPD officials there had been good results with biological warfare field trials using houseflies at the Suffield Experimental Station. But experiments with fruit flies had proven disappointing. He suggested some experiments be moved to the U.S. biological weapons proving ground at Horn Island, off the coast of Mississippi. The U.S. researchers agreed, and so Canada joined Camp Detrick’s Project ONE – “ONE” being a strained acronym for the Army’s “Joint Insect Vector Project,” utilizing the second letter from each word.

The Horn Island tests were supervised by the U.S. Navy. The Canadians supplied the flies. Project ONE tests included the examination of insects native to Polynesia, and tested strains of salmonella, shigella, and tularemia, as well as botulinus toxin. The tests ran well into 1945. (See Bryden, pg. 214.)

The last of the major World War Two era field tests at Suffield, in the weeks just before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, concerned transmission of disease to food from flies released from 500 lb. cluster bombs. It’s not known what the results were. But this last experiment puts the lie to claims that Canada was not involved in offensive biological weapons research, and demonstrates its manifest interest in the development of munitions based on release of infected insects.

“Considerable study has, of course, been made”

An excellent snapshot of the state of Canada’s study of use of insect vectors for biological warfare can be discerned from an August 4, 1949 “Secret and Personal” report from the Defence Research Board’s Scientific Intelligence Division (SID). Signed by SID’s director, A.J.G. Langley, the report looked at “Possible use of insects as BW vectors,” particularly use of flies, fleas, lice and ticks.

The document clearly shows that in the immediate years post-WW2, the plans surrounding use of BW was aimed primarily at the Soviet Union. Hence, the report’s focus on areas north of latitude 45º North.

The beginning of the Langley report clearly shows that work on living BW vectors, including insects and “rodents, etc.” had already been long underway.

“Considerable study has, of course, been made,” the report begins, “in the dissemination of BW agents via insects, rodents, etc. in special localities, i.e. the propagation of lice-borne typhus fever, flea-borne bubonic plague, tick-borne encephalitis, etc., but it appears that further studies of such possibilities are required….”

Langley described recent activities by Canada’s Bacteriological Warfare Research Panel:

At the 5th meeting of the B.W. Research Panel held on 20th January, 1949, Dr. Reed raised the point that the major effort on B.W. dissemination is on air-borne infections and that other methods should not be ignored. He referred to work on ground contamination, the use of containated fly baits, and the use of flies as vectors. Dr. [Charles A.] Mitchell said it would be valuable to have information on the insect pests found in the larger populated areas of likely enemy countries, with a view to testing them as possible carriers. The Secretary of the B.W. Research Panel, wrote to the Entomological Research Panel for the above information.

Reed’s own work on insects and biological warfare has already been described above. Charles A. Mitchell was chief of the Department of Agriculture’s Animal Diseases Research Institute in Hull, Quebec. He was also a member of the DRB’s Bacteriological Warfare Research Panel.

The Langley report showed that there was ongoing cooperation on BW matters between the BW Research Panel, the Entomological Research Panel, and three other divisions with the Defence Research Board, namely the Directorate of Scientific Intelligence (DSI), the Joint Intelligence Bureau (JIB), and Arctic Research.

The intelligence work on determining insect vectors of interest were sometimes carried out by covert means. One example was masking exploration of possible Soviet and East European (“satellite”) BW-associated entomological research behind exchanges of interest with other scientists on butterfly and moth distribution (Lepidoptera).

The report ended with a terse item re the “possibility of the existing more or less innoxious biting flies being used as B.W. vectors.” The idea that Canada had no interest in using insects as vectors of biological warfare had no basis in actual fact.

The Tripartite Agreement and the Korean War Years

As the late Canadian historian Donald Avery described in his 2013 book, Pathogens for War: Biological Weapons, Canadian Life Scientists, and North American Biodefence (University of Toronto Press), after the drawdown in military spending in the immediate aftermath of the end of World War Two, by 1947, Canada, the U.S. and the United Kingdom had resumed their wartime research collaboration on biological warfare.

A year earlier, Canada’s chemical and biological warfare programs were organized under the newly baptized Defence Research Board. Dr. Omond Solandt, who was Superintendent of Operational Research for the British Army during the war, was put in charge.

In August 1946, the Canadian, British, and American Tripartite Military Agreement on Chemical and Biological Warfare was formalized, and the first of what would be annual meetings between the three countries began the next year. Back in the United States, also in August 1946, the World War Two era U.S. Chemical Warfare Service was reorganized as the U.S. Army Chemical Corps.

As historian Albert J. Mauroni described it in “America's Struggle with Chemical-biological Warfare”, “The annual ABC (America-Britain-Canada) conferences combined British expertise, American resources, and Canadian testing grounds” (pg. 20).

Avery, now deceased, was one of the few historians to write in detail about this history, much of the documentation for which still remains classified to this day. He described in Pathogens for War how in summer 1947, Kingston’s Reed was asked to prepare a report “on major trends in offensive BW development” (e-page 1948).

In 1949, Reed undertook a study on “Possible Use of Insects as BW Vectors — Scientific Intelligence Aspects.” The project had the backing of DRB’s Bacteriological Warfare Research Panel. While supposedly advancing public health and insect abatement issues, the work also was “for [the] purpose of B.W. attack in areas outside Canada having an insect infestation similar to certain Canadian areas.” (Avery, e-page 1951). Reed hoped the Tripartite team would work together gathering a comprehensive list of insect vectors. Avery states this didn’t happen, but one wonders if that changed over the next few years.

According to Avery, “The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 produced intensified interest in Canada’s biological warfare program. As a result, the Defence Research Board once again asked Guilford Reed to provide an update of the major scientific and technology developments that had occurred in the biowarfare field, based on open and classified sources.” (Avery, e-page 1945-1946).

Reed complied. The Tripartite group had made decent progress and conducted field trials – presumably at Suffield – on anthrax, Brucella suis, Francisella tularensis, Yersinia pestis and botulinum toxin. According to Avery, “DRB had not yet developed an effective BW dispersal system, although several options had been explored…” including bombs, sprays, and insect vectors. “Reasonable accurate estimates [had] been made of the rate at which house and fruit flies distribute bacteria of the enteric and dysentery group of bacteria from contaminated baits to human or animal foods.” (Avery, e-page 1948-1949).

The bait idea was of unique Canadian origin. The breeding and storage of insects in the amounts needed for use in insect-vector munitions was a problem. Reed and his associates had hit upon the idea of utilizing native insect populations, infecting them by widespread use of infected baits dropped in the area under BW attack.

From an operational standpoint, Reed told the DRB, there were still issues in vaccine supply – an essential aspect of operational use of biological weapons – as well as “problems in surveillance and detection.”

Working with both U.S. and British scientists, Canadian BW research extended far beyond insect vectors. Ft. Detrick researchers used the DRB’s Grosse-Île facility for research on anti-animal pathogens because facilities to work with “exotic and dangerous animal pathogens… were not available in the United States.” The pathogens included “African Swine Fever, Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis, Newcastle dicers, fowl plague, hog cholera, rabies, and Rift Valley Fever.” (Avery, e-page 1952)

The large Suffield Experimental Station in Alberta had by this point “assumed a major role in carrying out biological weapons trials for American and British military planners” (Avery, e-page 1953). Biological field tests were conducted on pathogens such as botulinum toxin [code name X], Francisella tularensis, and Brucella suis, the latter a particular favorite of the U.S. Chemical Corps because its high infectivity meant greater facility in the incapacitation of enemy troops.

According to Avery, scientists at Suffield, Detrick, and the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah worked together on various joint projects: “Fort Detrick had a large number of chambers to do highly specialized operations. Suffield had a rather exclusive wind shed with a facility for doing other specialized operations. Dugway had not chambers or wind shed but they had a large amount of available space” (ibid.).

“Collaborating with the Japanese bacteriological war criminals…”

On 22 February 1952, the Foreign Minister of the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea, Bak Hon Yong, released a statement charging the U.S. with waging biological warfare. Two days later, Chou En-lai (Zhou Enlai), Foreign Secretary of the People’s Republic of China, also publicly charged the U.S. with similar attacks in northeast China.

Bak’s statement read in part:

According to authentic data available at the Headquarters of the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteers, the American imperialist invaders have, since January 28 this year, been systematically spreading large quantities of bacteria-carrying insects by aircraft in order to disseminate contagious diseases over our frontline positions and our rear….

In perpetrating these ghastly crimes, the American imperialists have been openly collaborating with the Japanese bacteriological war criminals, the former jackals of the Japanese militarists whose crimes are attested to by irrefutable evidence. Among the Japanese war criminals sent to Korea were Shiro Ishii, Jiro Wakamatsu and Masajo Kitano.

Presumably the DPRK and the Chinese had intelligence regarding the presence of Japan’s former Unit 731 personnel among U.S. military units associated with biological warfare. It would take another long article to document what is known about Ishii and Japan’s biowarfare project’s links to components of the American military, such as the U.S. Army Medical Corps or the U.S. Far East Medical Section’s Unit 406 Medical Laboratory.

Readers can follow up this aspect of the history in Japanese historian Takemae Eiji’s book, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy (Continuum Publishers, 2002), along with Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagerman’s comprehensive monograph, The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War and Korea (University of Indiana Press, 1998).

The association between Japan’s World War Two biological warfare program and the kinds of attacks reported against the DPRK and China in 1952-53 was something “which could hardly have been absent from the minds” of members of the International Scientific Commission (ISC). The ISC issued a report in September 1952 validating the Communist charges. Led by famed British scientist Joseph Needham, and six other Western scientists, as well as one Soviet and one Chinese scientist, the ISC began their report with a consideration of the probable Japanese links.

There was nothing in the ISC report, or any other investigation into the alleged biological warfare charges, linking Canadian research on biological weapons and insect vectors to the U.S. biowarfare campaign. This is not surprising as the work was top secret, and even today, seventy years later, much remains classified or lost, and information about Canada’s BW program during the Korean War remains quite thin.

James Endicott may have had connections in government that told him more than he felt safe revealing. In his pamphlet, I Accuse, written in summer 1952 at the height of the controversy over the germ warfare charges, there is only one mention of Canada’s biological warfare program.

“In South Alberta, on a vast area . . . the Suffield experimental station has gained world-wide renown for its field experiments in Chemical and biological weapons” (ellipses in original). This quote, however, is not from Endicott himself, but he cites it in the pamphlet, and indicates it appeared in Reader’s Digest magazine in January 1951. This was the safe way to reference material that otherwise Endicott’s enemies might have used to prosecute him.

The repression and legal and bureaucratic obstacles to investigating Canada’s biological and chemical warfare research, as well as its tripartite cooperation with similar programs in the U.S. and the UK, has long prevented historians and journalists from knowing the full impact of that research, even if the occasional article surfaces. Only very recently has the extent of U.S. governmental covert operations against proponents of the germ warfare charges in the West been more fully revealed.

But given the close cooperation of Canadian scientists with their peers at Ft. Detrick and Porton Down, including research concerning insect vectors and dissemination of same in offensive biological weapons, it seems highly likely that when governmental archives are finally fully opened, the world will see that Canada played an important, and possibly essential role in the planning and implementation of the covert biological warfare program run by the United States during the Korean War.

Endicott speaks before thousands

On Sunday 11 May 1952, Dr. Endicott appeared before approximately eight to eleven thousand attendees at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens. He was the featured speaker at a rally commemorating the close of a three-day session of the Canadian Peace Congress. According to Endicott’s biographer, son Stephen Endicott, in his 1980 book, James G. Endicott, Rebel Out of China (University of Toronto Press), the meeting was threatened by Endicott’s “opponents [who] arrived at Maple Leaf Gardens with eggs, tomatoes, firecrackers, stink-bomb, and placards” (pp. 295).

In response to the threat, Peace Congress officials had called upon five hundred “peace supporters, seamen, auto-workers, steel and electrical workers, miners from Sudbury, and other trade unionists” who volunteered to protect the meeting. In the end, there was no significant disturbance (p. 296). The Canadian government intervened to the extent it could by preventing black scholar W.E.B. DuBois from crossing the U.S. border to address the meeting.

Speaking to the crowd, Endicott ridiculed the attempts to legally silence him. “Their charges came in like a lion and went out like a lamb,” he said (p. 297). He noted that he had volunteered to appear before his governmental accusers, but they had refused.

As early as 1 April, 1952, Endicott had cabled External Affairs Minister Lester Pearson: “PERSONAL INVESTIGATIONS REVEAL UNDENIABLE EVIDENCE LARGE SCALE CONTINUING AMERICAN GERM WARFARE ON CHINESE MAINLAND URGE YOU PROTEST SHAMEFUL VIOLATION UNITED NATIONS AGREEMENTS."

But Canada’s government did nothing, except make threats against Endicott. For his part, Dr. Endicott continued to make his germ warfare charges. In July, before an audience of 400 at the Dreamland Theatre in Edmonton, Endicott lambasted a report by three Canadian scientists whose criticism of the BW charges was being used by the Allies to discredit the Communist BW charges internationally. Endicott also accused the Americans and their allies of killing “600,000 women and children… in Korea by Napalm, jellied gasoline.”

Note: A follow-up article by this author will consider the critique made by the three Canadian scientists.

In Dr. Endicott’s pamphlet, I Accuse, published after the May 1952 speech, the former missionary, turned activist against imperialist war crimes, asked the public:

If you had seen what I have seen, what would you say?

What would you say if you had seen with your own eyes sections of the brains of children who had died from acute encephalitis following germ-war bombardments by U.S. aircraft?...

If you had talked to churchmen and Red Cross officials who thoroughly confirmed what the others said?

If as a result of all this you found out beyond reasonable doubt that germ warfare had been committed, what would you say?

Would you be silent? That would make you an accomplice.

Or would you speak out?