Secret UK Briefings: U.S. Biowarfare Program Underwent "Chaotic" Period After the Korean War

UK declassified documents show in aftermath of the Korean War, conditions at Camp Detrick's BW program had become "unstable," "very unsettling," with constant resignations by "demoralised" scientists

“Biological warfare is essentially public health and preventive medicine in reverse.” - William Creasy, Brigadier General, U. S. Army Commanding General, Chemical Corps Research and Development Command, Armed Forces Chemical Journal, January 1952, pg. 18

One of the more unexpected findings in my research on the U.S. biological warfare (BW) program and the decision to use germ warfare during the Korean War, was that there was a good deal of conflict within the military services, as well as among U.S. international partners in regards to operational use of bacteriological weapons.

Taking a hint from Brian Balmer’s excellent 2001 book, Britain and Biological Warfare: Expert Advice and Science Policy, 1930–65, I obtained declassified former top secret minutes of meetings of the UK Ministry of Supply’s Biological Research Advisory Board (BRAB). The board “was accountable primarily to the Advisory Council on Scientific Research and Technical Development of the Ministry of Supply but provided technical advice to the [Inter-Services Subcommittee on Biological Warfare]. The Ministry of Supply, in turn, was responsible for carrying out biological warfare research and development at the Microbiological Research Department (MRD)” at Porton Down” (Balmer, pg. 60).

Balmer’s book briefly described some of the controversies and conflicts inside the U.S. BW program at the close of the Korean War, but it seemed possible there was more to know. In particular, it seemed important to assess the information about UK reactions to the U.S. program in the light of other evidence I had gathered concerning opposition to American germ warfare plans and operations.

The BRAB minutes from February and June 1954 described trips top UK biowarfare officials made to visit colleagues at the main U.S. biological warfare facility at Camp Detrick, Maryland. (Camp Detrick became Fort Detrick in 1956.)

The minutes revealed that, in the wake of changes happening to their ostensible BW partner since the end of the Korean War, leading British BW officials felt the U.S. had become an unreliable, if not unstable collaborator as regards BW activities. The British had plenty of opportunity to assess their U.S. partners. They were formally in league with both Canada and the United States in a tripartite agreement to coordinate research on chemical and biological warfare. This included exchanges of personnel, a division of labor between the countries’ BW programs, and official annual meetings between the participants.

According to Balmer, as early as March 1952 — only weeks after both Chinese and North Korean officials had publicly condemned the U.S. for dropping biological bombs over North Korea and Manchuria — David Henderson, Superintendent at the leading UK biological weapons research facility at Porton Down, had warned BRAB members, “‘American colleagues of long standing had become offensively minded,’ wishing to end the Korean War as soon as possible. Similarly, Henderson felt that the US Services had developed a ‘most aggressive outlook’ with the consequence that the U.S. BW focus had shifted to short-term projects on anti-personnel and anti-crop weapons” (Balmer, pg. 136).

Henderson, who died in 1968, was not one to make snap criticisms. He was passionate about the BW work. He also had plenty of contacts in the U.S. biowar program. According to a November 1970 obituary in Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Henderson had spent the latter years of World War II shuttling back and forth from Porton Down to Camp Detrick, working on BW experiments and field trials. His contributions on calculating “more accurate estimates of infective dosages” benefitted the U.S. biowar project. Henderson was “a valuable and fruitful collaborator with a number of American microbiologists… making friendships there which survived to the end of his life. In 1946 Henderson was awarded the U.S. Medal of Freedom, Bronze Palm” (pg. 335).

According to historian M. Susan Lindee, “the British biological warfare laboratory established at Porton Down in 1940” is located “on the Salisbury plain near Stonehenge.” The facility has long been controversial. Lindee described it as “a restricted and highly controlled space for the production of secret knowledge,” operating “at the margin between the public and the secret, between offensive and defensive knowledge of pathogens, and between military research and health-care research.”

“Porton Down,” Lindee concluded, “is a place where the contradictions of twentieth-century biomedical science are clear and compelling.”

The Superintendent at Porton Down was not alone in his anxieties about the U.S. “aggressive outlook.” A number of top-level scientists in the UK biological warfare program at the time of the Korean War, including Air Ministry Advisor, Robert Cockburn, and Defence Research Policy Committee (DRPC) Chair, Sir Henry Tizard, were skeptical about use of BW as an offensive weapon.

Unspoken was the fact that, according to Henderson’s obit, in the years after World War II there was a reaction in the scientific community “against all activities associated with war and the opprobrium associated with biological work in this field.” Opponents to biological warfare research had “an active but often ill-informed lobby against it.” (How or why “ill-informed” the authors didn’t say.)

Still, according to Balmer, the partisans of research into offensive biological weapons, led at the time by Britain’s military Chiefs of Staff, had a tentative upper hand in these matters. “The Air Staff still had a requirement for a complete biological bomb and the target date had apparently moved from 1957 to 1955” (Balmer, pg. 138).

The bureaucratic battle between the more offensively minded and those seeking a slower, more conservative pace to BW research led to a stand-off during the Korean War. Hoping to settle the controversy over undertaking offensive research, a DRPC “working party” led by Cockburn concluded that BW research in general should continue, but “recommended against mounting operational biological weapon production in the UK as there were still ‘far too many unknowns.’” (Balmer, pg. 139)

Balmer further described the widening gulf between the U.S. and UK attitudes regarding biological weapons research: “BRAB members regarded the divergence in the two countries’ attitudes [on offensive use of BW] as problematic and expressed concern at the May [1952] meeting of the board that ‘the US might use biological weapons in Korea.’” (Balmer, pp. 136-137, bold added for emphasis) The conditional nature of the threat, as Balmer recorded it, belied the fact that U.S. biological weapons attacks had already taken place.

As the Korean War dragged on, with increasing levels of destruction, British scientists, who presumably were aware of the Communists’ BW charges against the United States — if they did not have even more secret knowledge that germ war was taking place — were backing away from the idea of using BW offensively. Increasingly, UK scientists and policy makers questioned the use of offensive biological weapons.

Scholars Gradon Carter and Graham S. Pearson wrote in an influential 1996 article that when it came to use of biological and chemical warfare, UK scientists had by 1952 believed “the employment of toxicological weapons would be justified only if they showed marked advantages over conventional weapons” (quoted in Balmer, p. 138).

"Toxicological weapons” were understood to include both biological and chemical weaponry, and poisons such as botulinum. Carter wrote, by the way, as an insider, as by the time he retired in 1990 he was Head of the Technical Intelligence and Information Section at the UK Biological Warfare center at Porton Down.

The British deemphasis on offensive BW continued apace each year. According to a 1998 article by John Agar and Brian Balmer, “[by] 1955 the DRPC’s Sub-Committee on Biological Warfare was dissolved” (pg. 220).

Earlier, in February 1954, only some six months after the end of the Korean War, Porton’s David Henderson, newly returned from a visit to Camp Detrick, had surprising news for the British BW establishment. He told BRAB officials that since the end of the war, “the morale of the [Detrick] research staff had suffered badly and many of the workers were seeking employment elsewhere.” [PDF pg. 3]

DR. HENDERSON stated that the organisation and policy of U.S.A for the control of BW research and development remained chaotic…. The Chemical Corps was still nominally in control at Camp Detrick, though a number of the directing civilian staff had been relieved of their appointments and had been restyled ‘monitors’…. [BRAB Minutes, February 19, 1954, PDF pg. 3, all caps in original]

What happened? Neither the BRAB minutes nor Balmer’s history of the period discuss any use of germ weapons in Korea (though they allude to the possibility). But it seems clear from the documentation available, and in the declassified histories from the period, that there was great disappointment in the U.S. with the performance of the biological warfare departments during the Korean War.

As the Korean War ended in an uneasy armistice, management of the BW project came under harsh assessment, and plans were put in motion to take the entire research enterprise away from Army management.

This is a topic that, to my knowledge, historians of the U.S. biowar program barely mention, with the notable exceptions of Balmer, and the Air Force’s Dorothy Miller, whose contributions are discussed below. I suppose this is because if they did research that period of disappointment, they would have to explain why the program was seen as a failure up to that point. True, it had taken the Army’s Chemical Corps longer than most had thought to develop the biological munitions they had fashioned on their drawing boards. Also, the U.S. emphasis on “short-term” end products for immediate use, i.e., in Korea, had come at the expense of longer-term research and development, but it’s difficult to understand the drive to overhaul Detrick’s BW management and the consequent demoralization of BW workers on these rationales only.

The article below will recount the events that took place in U.S. biological warfare circles at the end of the Korean War, a story that was briefly told by Balmer, but not in as much detail as here. The window provided by such events allows the reader even greater insight into the workings of the U.S. BW program reaching back into the Korean War period itself.

As a matter of context for the period 1953-54, it’s recommended readers peruse this examination of Eisenhower’s Operations Coordination Board (OCB) actions to counter the stubborn acceptance by some of the Communists’ charges of U.S. use of biological weapons during the Korean War. OCB tasked the CIA to undertake covert actions on this score, namely the use of “counter-propaganda and personalized seduction and coercion” to be “initiated as a matter of urgency against persons and groups where the Soviet campaign [to publicize U.S. use of germ warfare in Korea] has been especially effective” (bold added for emphasis).

Controversies in the BW War

In an August 2022 article at Medium.com, I described how in the first years of the Korean War the funding for secret production facilities for at least some of the biological warfare projects, as well as for producing Sarin gas, “were hidden in the guise of special Army military personnel directives (MPAs).” The entire funding process, code-named SKELP, took place outside normal appropriation channels. The article further described how conflict over these programs led to a sudden suspension of the secret BW funding on the very eve of the U.S. biological bombing campaign, which began in late December 1951. The pushback on the programs came from the Army’s Munitions Division. In the end, however, and with vociferous lobbying from the Chief of the Chemical Corps, the funding was restored via a different, albeit secret, bureaucratic mechanism.

A different kind of opposition to the BW program came from Air Force officers involved themselves in the germ war program. Many of these officers were shocked and upset by the decision to use biological weapons, as described in the depositions some of the captured flyers gave to their Chinese captors.

As one example of the flyers’ reaction to the BW missions, USAF pilot Lt. Floyd O’Neal, who was shot down and captured by Chinese People’s Volunteer forces in March 1952, told investigators from the International Scientific Commission (ISC) later that summer how some of the flyers reacted to the germ war missions:

I know from our observations of other pilots when they had been on the germ missions — they would be rather conspicuous by their silence, for usually the pilots would be very talkative among one another all during the day, telling each other what they had done, telling new jokes, the news from home, and those things. But those who had been on a germ mission would just be terribly gloomy. They would usually be found in the [officers’] club in the evening, trying to drink away their troubles [pg. 5].

Another instance of such opposition leaked around the controversy in the U.S. press concerning excess bombing “duds,” which surfaced briefly in June 1952, in the midst of the germ war campaign itself.

Air Force personnel were warning about the high number of “duds,” that is, unexploded bombs among those they were dropping. They leaked their concerns to the press and friendly members of Congress. It was well-known at the time, from reports published in the U.S. press, that captured American POWs had told the Chinese that the germ bombs were described in U.S. reports as “duds,” the better to disguise their use. It seemed likely that those leaking the “duds” information were hoping that Congress would look deeper into the situation, and perhaps discover the germ war underway. But the “duds” controversy did not get the hoped-for Congressional investigation, or detailed examination by the press, and faded quickly from view.

Another aspect of the controversies that rent the BW program were examined in an Air Force history of participation in the biological warfare program during the Korean War, and its immediate aftermath. One aspect that Air Force historian Dorothy Miller wrote about in her top secret January 1957 history of the subject (declassified, though still with many redactions, in June 1978) were the struggles around management of the program.

“It was no secret that the Air Force was dissatsified with the results of [Army] Chemical Corps research in biological warfare,” Miller wrote. “The Secretary of the Air Force [Thomas Finletter], concerned at the slow progress being made, wondered if management problems were responsible.” (Miller, pgs. 62-63)

The “slow progress” of the main BW program meant, under the blows of the Korean War, that some expedient measures had to be taken. As a 1953 Chemical Corps “Summary History” retrospectively explained the situation, “During the period 9 September 1951- 31 December 1952, the Chemical Corps was principally concerned with the support of the Korean War and with the improvement of the Bacteriological Warfare (BW) and Chemical Warfare (CW) capabilities of the Armed Forces in the event of an emergency and in defense against radiological attack (RW).” [p. 1]

In a key passage, the “Summary History” described the work done, albeit in vague terms:

Thanks to the world situation of limited war the research and development programs were directed at the immediate completion of short-term developments where immediate benefit to operational effectiveness would result. Although some of these developments were admittedly stop-gap measures, such as the M114 biological bomb, they provided something to use if it were required. At the same time developments were accelerated in order to ease the greatest operational deficiencies. The emphasis was therefore placed on end items in all fields, weapons and munitions for the dissemination of nerve gases (G-agents), and the entire field of biological warfare. [p. 13, bold added for emphasis]

According to Miller’s history, during the period leading up to the Air Force “crash program” to operationalize biological weapons during the Korean War, the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff, Development, “had said repeatedly that planning was being based on over-optimism, both in respect to the date of availability of biological munitions and their effectiveness.” (Miller, pg. 69) The Deputy Chief of Staff, Development is not named in Miller’s history, but apparently was Lt. General Laurence C. Craigie, who served in that role from 1951-1954.

Besides the M114 biological bomb, what were the “stop-gap” measures undertaken? The declassified U.S. records do not say, but Communist forces at the time presented evidence that the U.S. Air Force and Army Chemical Corps decided to utilize former Japanese Unit 731 personnel to obtain “end products” for immediate BW use in the war.

The U.S. biological weapons were, as contemporary investigators such as British scientist Joseph Needham believed, eerily similar to those of Imperial Japan’s BW organization, Unit 731, led by Lt. General Shiro Ishii. The widespread use of insect vectors had been particularly favored by the Japanese. (See the 1952 ISC report, pg. 11-12.) Insects had also been intensively studied in this same period by the U.S.’s BW partner, Canada, though it’s unclear if anyone on the ISC or in China or North Korea were aware of that at the time, though it’s possible that they read reports on the Canadian efforts from United Christian Church missionary, and former OSS agent, James Endicott.

The ISC report stated:

It should not be forgotten that before the allegations of bacterial warfare in Korea and NE China (Manchuria) began to be made in the early months of 1952, newspaper items had reported two successive visits of Ishii Shiro to South Korea, and he was there again in March. Whether the occupation authorities in Japan had fostered his activities, and whether the American Far Eastern Command was engaged in making use of methods essentially Japanese, were questions which could hardly have been absent from the minds of members of the Commission [ISC report, pg. 12].

…. The Commission has come to the following conclusions. The peoples of Korea and China have indeed been the objective of bacteriological weapons. These have been employed by units of the U.S.A. armed forces, using a great variety of different methods for the purpose, some of which seem to be developments of those applied by the Japanese army during the second world war. [Ibid., pg. 60]

But when it came to the official, on-the-books U.S. BW program — that is, the weapons programs briefed in classified sessions to Congress — Finletter’s bureaucratic response to its slow development was to form a “civilian committee.” Finletter planned to appoint a panel led by Air Force General J.H. Doolittle “to examine the potential of the biological warfare program, with particular reference to organization and management aspects.” (Miller, pg. 63) But faced with opposition from inside the Army and the Pentagon’s Research and Development Board, the Doolittle committee proposal never got off the ground.

Management issues

That a concerted air campaign using biological weapons was launched by the U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps in the winter of 1951-52 seems a near certainty, after the release of declassified CIA communications intelligence reports that describe at least two dozen intercepted North Korean and Chinese decrypted military communiques about the problems faced dealing with the germ war attacks. If bacteriological weapons were meant to strangle the logistics lines of the Communist forces, and sew panic among the populace, the campaign failed to materially affect the course of the war, so far as we know.

Faced with what appeared to be the failure of the BW program in Korea and China to bring about the desired results in neutralizing the opposing armies, according to Miller a new “proposal to improve [BW development] management had contemplated withdrawing the [BW] program from the services and placing it under an agency similar to the organizational structure of the Atomic Energy Commission [AEC]. The argument was that such action would minimize dominance by a single service, eliminate interservice competition, and consolidate objectives and policy.” (Miller, pg. 63)

What would AEC management have looked like? An October 1953 article in the Armed Forces Chemical Journal, “The Civilian Scientist and the Military Establishment,” provided such a picture. It was written by a long-time BW consultant to the military, Dr. W. Albert Noyes, Dean of the Graduate School at the University of Rochester.

Noyes had an interesting history. He had been a member of the Counter-Intelligence Corps’ World War II Alsos Mission, a secret effort to hunt down Nazi nuclear, biological and chemical warfare scientists. A smaller version of this project had also taken place in Japan. A few years later, in 1948, Noyes had led a Research and Development Board panel to assess the possible military benefits of chemical, biological, and radiological weaponry.

Writing of the possible benefits of “utilizing civilian scientists for research and development work of the Armed Services,” Noyes 1953 article referenced the AEC.

“The Atomic Energy Commission has used the contract method for its major installations such as Oak Ridge, the Argonne Laboratory, and Brookhaven. The contractor has somewhat greater freedom to hire and fire than if these installations were under civil service, and moreover there is probably greater freedom to purchase materials and provide competent direction. This type of global contract has not been used heretofore in the Department of Defense, but some consideration is being given to its introduction.” (Noyes, pg. 11)

One can only imagine the shivers sent down Chemical Corps scientists’s spines as they read about the “greater freedom to hire and fire,” not to mention the swipe about “competent direction.”

Nevertheless, by the close of his article, Noyes had rejected the AEC model. Note his description of the BW research effort:

Our research and development effort has more or less grown like topsy with much duplication of effort and without adequate placement of responsiblity at the level where the actual work is being done. We need to examine our structure to decide where the wastage of money and of personnel is occurring, but we could not change to a completely civilian picture without a major upheaval. This we cannot afford to do in the present unsettled condition of the world. We must rely, for the time being at least, on patchwork remedies and our main effort should be devoted to placing competent persons in key positions.

In her history of the period, Miller addressed the “duplication of effort” and the “wastage of money and of personnel,” pointing out that the “management problems [in BW work] had their origin in the fact that so many agencies were involved in the program,” and the tendency for each party “to advance its own interests.” [Miller, pg. 64]

Citing the M33 biological cluster bomb, with an official payload of Brucella suis, which causes undulant fever, Miller described the BW munition as “extremely disappointing to the military user.” It needed “an excessive amount of logistic support…. Munition expenditure rates could not be calculated except for a narrow range of target conditions… Almost nothing was known of the effects an attack would have upon a nation’s economy.” (pg. 52)

Miller concluded, “It was evident that the available test data did not justify the emphasis that had been given to procuring biological warfare munitions. As a result, acute disillusionment was experienced by many former enthusiasts, and the prestige of the entire biological warfare program suffered a damaging blow.” (Ibid.)

It is difficult to believe this conclusion was due solely to the deficiencies of the M33 bomb. More likely, the problems stemmed from the entire experience of the BW Korean War campaign. Indeed, Miller stated further on in her report that the Air Force’s own “crash program to obtain an operational readiness” [pg. 69] in BW, beginning in January 1952, had been “conceived in an emotional atmosphere that did not engender a calm appraisal of the potential of biological warfare…. by early 1953, it was painfully clear that the entire biological warfare program needed an overhauling” [pgs. 71-72, 75].

It was a sobering period for the BW proponents. By October 1953, the “crash program” was officially discontinued. Miller dryly noted, “The military services realized that they had reached the point of diminishing returns on the development of existing end items” [pg. 79].

“Emphasis was to be placed on the development of a lethal anti-personnel biological munition for release from high speed aircraft and upon the development of munitions for delivery of anti-crop pathogens from high speed aircraft and by balloons.” [Ibid.]

The U.S. use of biological pathogens delivered via the E77 bomb attached to high-altitude balloons, on the Japanese model, will be the subject of a forthcoming article. (The reader can peruse Miller’s own discussion on the topic in her history, pgs. 111-116.)

“A Contract with Industry”

Despite the rejection of a BW privatization effort by Noyes and others, the threat to turn the BW program over to a private “industrial concern” had already been partially realized, according to a 1958 in-house history of the biological warfare program at Fort Detrick.

By Spring 1953, research and development (R&D) work on developing BW munitions had been farmed out to a contractor. According to Dr. Henry I. Stubblefield, who had been a key figure in obtaining U.S. amnesty for Japan’s Unit 731 war criminals, and the author of the in-house Detrick history, “A Resume of the Biological Warfare Effort,”[1] the new munitions R&D contractor was the Ralph M. Parsons Company, who “used Camp Detrick and Dugway [Proving Ground] facilities, staffing them with their own employees. The majority of technical people were Detrick personnel employed by the contractor” [pg. 29]. The Parsons contract was terminated in December 1955, ostensibly due to “budget cuts.”

Stubblefield, who worked in Detrick’s Research and Development Division, described in greater detail the effort to farm out all of the R&D work on biological warfare, beyond the work on munitions:

“In July 1953 [the same month the Korean armistice was signed — JK], the AC/S G-4 [U.S. Army Assistant Chief of Staff, Logistics] directed the Chief Chemical Officer to take steps to secure a contract with industry to operate the entire Research and Development program in BW — the contractor to use the facilities, laboratories and buildings of the Chemical Corps as well as other facilities. Several firms expressed interest and their representatives were briefed and taken to visit the facilities at Camp Detrick, Dugway Proving Ground, and Production Development Laboratories. The Mathieson Co. was recommended, formal negotiations began in Oct. 1953. It was expected that the contract would be signed late in Dec. [?] However, on further consideration, officials for the company decided not to undertake the work.” {pg. 29, bold added for emphasis]

The proposal to have the U.S. BW program essentially farmed out to private contractors faltered when the only company willing to bid on the program, the Mathieson Chemical Corporation, decided against accepting the proposed contract. In the wake of the controversies over allegations of U.S. use of biological weapons in the Korean War, BW was a hot potato, or at least that is my surmise as to why the Pentagon could not find a buyer for its BW reorganization.

The suggestion of reorganizing the BW R&D program under a new umbrella, and the creation of a new ostensible civilian agency, like the AEC, for BW was dropped. In her history of the Air Force participation in the BW program, Miller barely alluded to how the 1953 controversies were roiling the BW community as a whole, and especially the primary agency involved, the Army’s Chemical Corps, centered at Camp Detrick. The BRAB minutes quoted below help describe what Miller overlooked.

Ultimately, according to the Stubblefield history, the BW shake-up led to the demise of the Pentagon’s Research and Development Board, a victim of the reorganization struggles inside DoD. The board, which had lobbied Congress for a huge hike in the Army’s BW budget in the early years of the Korean War, was dissolved in late 1953, replaced by a new office, Assistant Secretary of Defense for R&D. Per this government history, former Bell executive Donald A. Quarles was the first occupant of the office (pg. 90). Quarles was “vice president of Western Electric and president of Sandia Corporation… a subsidiary company of Western Electric responsible for operating the Atomic Energy Commission’s Sandia National Laboratory in Albuquerque, New Mexico.”

Quarles seemed like just the guy to push for privatization of the BW effort.

The Scheele Committee & the St. Jo. Program

Stubblefield’s account of the biological warfare effort in the period preceding and then during the Korean War provides a sense of the ferment that stirred the military BW world during that time:

The period 1947 to 1952 was an era of boards, committees, Ad Hoc groups, panels, contractors, etc. investigating, evaluating, and advising on various phases of the BW program. (At one time during a period of a few months, 23 such groups were engaged in studies and surveys.)….

The Korean War served to stimulate interest and action in BW which resulted in more liberal budgetary support; additional laboratories, pilot plants and testing facilities were built. [Stubblefield, pg. 28, parentheses in original]

According to Stubblefield (pg. 30), “The beginning of the Korean War (June 1950) marked a sharp trend upward in R&D funds” for the Chemical Corps, from just under $4 million in 1949 to just over under $10 million in 1951, the first full year of the war. The funding jumped again a year later to over $15 million in 1952. The latter represented approximately $172,000,000 in current dollars.

Civilian consultants had long been involved in the BW program. Johns Hopkins University’s Operations Research Office (ORO) acted as an Army research program during the Korean War, including assessment of biological munitions.

In or around 1953, according to the Stubblefield document, the Scheele Committee utilized government civilian consultants from the the U.S. Public Health Service, the USDA, the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board, ORO, and other agencies, to help the Chemical Corps determine what the median lethal dose (LD50) for an anthrax bomb would be, in order to determine “munition efficiency…. under field conditions,” as tested at Dugway Proving Grounds (DPG) [Stubblefield, pg. 28].

In 1954, under the leadership of U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Leonard A. Scheele, the “Ad Hoc Committee on BW Testing at DPG” concluded “anthrax bombs of limited charge could be tested with safety.” (Ibid.) The testing program began using anthrax in the E61, or “hourglass” bomb “under the name St. Jo. Program” . “Significant numbers of exposed animals were infected” with anthrax, even 40 miles downwind [Stubblefield, pg. 29].

The St. Jo. Program, under the name “Exercise St. Jo.” would be referenced in the BRAB minutes (see below), which indicated it was part of a U.S. reassessment of its BW program after the Korean War.

Meanwhile, as discussed above, to visiting British scientists the U.S. BW program appeared in an uproar. The BRAB minutes make the situation appear fairly dire for the time. The American program was described as “chaotic,” under “constant changes of policy,” in “a state of continued instability,” with mass resignations and “demoralized” scientists. None of this was hinted at in Stubblefield’s history, and is only vaguely discussed by Miller.

While I cannot pretend to know the full extent of the situation in the post-Korean War BW program, from the above discussion it appears that the failure to achieve a knockout blow via BW in Korea had led to a period of great upheaval in the BW program.

Two BRAB Meetings

The following describes the relevant points on the U.S. biological warfare program gleaned from the UK BRAB minutes released via UK FOIA to this author.

Professor Sir Edward Charles Dodds chaired the February 19, 1954 BRAB meeting. Dodds had been recently knighted. He was the long-time Chair of Biochemistry at the University of London and Director of the Courtauld Institute of Biochemistry. Like others at BRAB, he was a high ranking member of Britain’s scientific elite.

Among other things, the minutes described Dr. David Henderson’s recent trip to America to visit colleagues at Camp Detrick. Henderson knew or had heard that there were changes in the U.S. BW program going on, and he and the UK BW establishment wanted to know more about it. He left for the U.S. on Feb. 9, 1954. By February 19 he had returned and reported on his visit at a meeting of the Biological Research Advisory Board.

The meeting was held in Room 140 at the Shell Mex House. For purposes of documentation, the following is taken from the author’s transcription of the meeting:

DR. HENDERSON stated that the organistation and policy of U.S.A for the control of BW research and development remained chaotic, and no decision had yet been made. The Chemical Corps was still nominally in control at Camp Detrick, though a number of the directing civilian staff had been relieved of their appointments and had been restyled ‘monitors’ to act as advisers to a newly appointed technical director. He in turn was at present responsible to a Service Officer of the rank of Colonel stationed at Camp Detrick, the representative of the Chief of the Chemical Corps. The proposal to transfer direction of research to an industrial concern, scheduled to take effect on 1st January [1954], had fallen through, since the only firm to tender, the Mathieson Chemical Corpororation, had finally decided not to accept the contract. As a result it had been officially decided not to pursue the question of industrial control further.

The Chief of the Chemical Corps, General Bullene, would be leaving at the end of March; his successor had not yet been appointed. Mr. Wilson, Secretary of Defence, would in future have a greater say in research and development for the Services.

As a direct result of these changes the morale of the research staff had suffered badly and many of the workers were seeking employment elsewhere.

There had also been changes in policy in Service requirements; thus the plan in operation at the beginning of 1953 for the production of Br. suis at Pine Bluff, which was threatened to be superseded by one for the production of anthrax spores, seemed again to be favoured….

DR. HENDERSON said that the future policy would depend on the Service with the greatest influence at the time; the U.S.A.A.F. wanted “N” [anthrax], the Army “US” [Brucella suis].[2] DR. CAWOOD said that it was at present difficult to have any views as to how the policy of this country [UK] would be affected. He hoped that developments would be more favourable to us than was the Mathieson project. It was true that we were depending on the United States for some things. THE CHAIRMAN recalled his report to the Minister after the members of the Board had visited America in 1952. In his report he had recommended that we should rely on American production for the present. DR. CAWOOD said that the Minister had been warned and would be informed more fully of the changes which had taken place.

What the British were depending on from the Americans was the production of biological pathogens for testing purposes, though not explicitly on the provision of biological weapons themselves. The British authorities had been tussling for some time about building their own BW pathogens production plant — known as “Experimental Plant No. 2” — but by 1954 the project was still controversial and nothing had been built.

During the period of the BRAB minutes discussed here, the UK was experimenting with Brucella suis in tests for Operation Ozone in the Bahamas. These were 74 spray tests held “some 60 miles south of Nassau…. Brucella suis, Bacterium tularense and VEE [Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus] had all been tested as aerosols in bright sunlight and had half-lives ranging from a few seconds to two minutes” [Balmer, pg. 124]. The U.S. had supplied the pathogens to the UK BW scientists for Ozone and similar projects.

Continuing with the BRAB minutes:

SIR PAUL FILDES emphasised the importance of informing the BW Sub-Committee [about the situation in America]. He informed the Board that he, Sir Charles Dodds and Lord Stamp, as independent members, had called a limited meeting of the BW Sub-Committee in order to place all the facts before the Chiefs of Staff Committee. SIR PAUL asked the Board to support this action.

DR. HENDERSON said that he had already informed Dr. Quarles, the American Assistant Secretary of Defence, that they were not relying on them for BW weapons, which he considered were not yet perfected. He had also discussed this with Dr. Vance, Assistant to General Uncles of the Army G4 Staff. In reply to Sir Paul, DR. CAWOOD explained that the provision of Exxperimetnal Plant No. 2 had been deferred, but not cancelled. DR. HENDERSON adds that the Americans were not incapable of production; future plans would depend upon what the research workers were allowed to do.

SIR PAUL felt that American production should not be relied upon. He was anxious that the Chiefs of Staff should know all the facts. DR. WANSBROUGH-JONES pointed out that the Sub-Committee had received a verbal report on the position in the United States from Dr. Henderson at their meeting on 17th February.

Detrick’s “inadequacy of organisation”

The issue of how the roller-coaster ride of U.S. BW policy during the Korean War had affected the U.S. program overall was then broached. Indeed, Porton Down’s Henderson had traced the problems back as far as September 1949!

THE CHAIRMAN [Sir Charles Dodds] asked for the recommendations of the Board on Sir Paul’s proposal to call a limited meeting of the BW Sub-Committee. DR. HENDERSON pointed out that, since General Waitt had ceased to be Chief Chemical Officer [in September 1949, followed by Anthony McAuliffe (1/49-7/51), Egbert Bullene (8/51-3/54) and, later, William Creasy (5/54-8/58) - JK], there had been constant changes of policy in the U.S. He cited the history of the Foot and Mouth Disease research programme as typical of this. Again, a proposal to replace the production of Br. suis by that of B. anthracis had been mooted but that this had now been discarded. SIR HOWARD FLOREY said that, in his opinion, the most serious aspect was the demoralising effect of constant changes in policy on the scientists involved.

Florey’s opinion was important. He was no mere apparatchik on the BRAB board. He had shared the Nobel Prize in 1945 with Ernst B. Chain and Alexander Fleming for the discovery of penicillin and its uses.

DR. WANSBROUGH-JONES read out the last paragraph of the Directive on BW which pointed out that, since the Americans were concentrating mainly on the development of weapons capable of early introduction into service, the U.K. programme of weapon development should put greater emphasis on the study of long-term projects. This was a sraight question for the Chiefs of Staff who should now be informed by the Board that, owing to the increasing inadequacy of organisation at Camp Detrick, which had led to a state of continual instablity, there was progressively less probability that a weapon capable of early introduction would be produced in U.S.A.

After further discussion it was agreed that the Board should support Sir Paul’s proposal to inform more fully a special meeting of the BW Sub-Committee of the state of BW research and development in the U.S.A.

The next set of minutes are from the BRAB meeting on June 15, 1954, which like the February meeting, was held at the Shell Mex House.

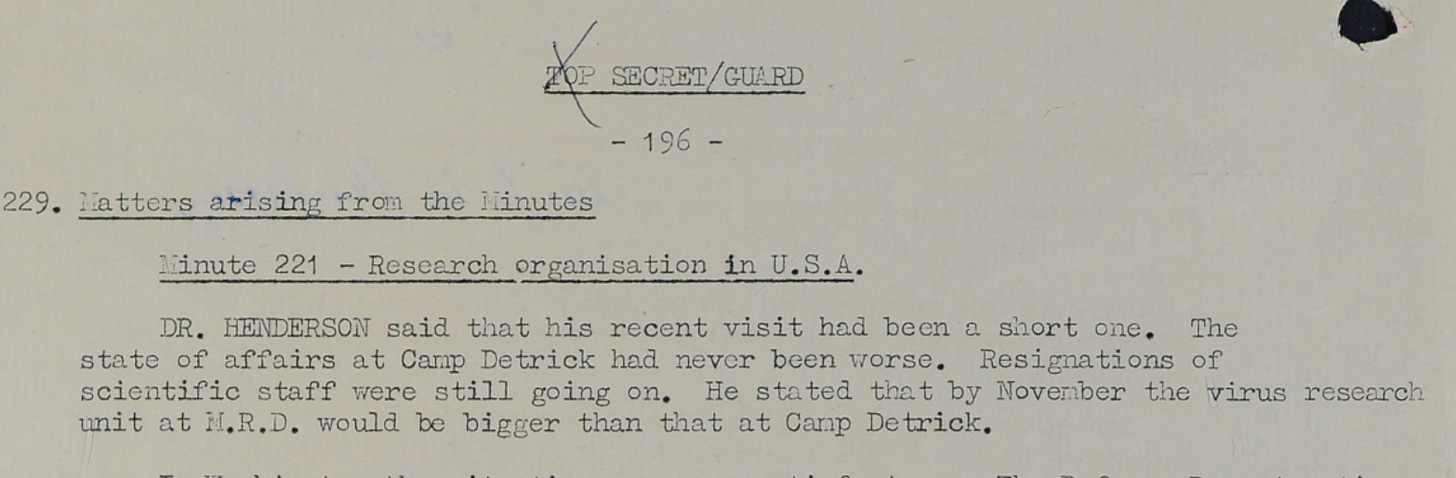

Under a point on “Research organisation in the U.S.A.,” Dr. Henderson reported on his most recent visit to Camp Detrick. The chaotic situation there had not improved. British scientists did not have confidence in the U.S. leadership, with a few exceptions.

DR. HENDERSON said that his recent visit had been a short one. The state of affairs at Camp Detrick had never been worse. Resignations of scientific staff were still going on. He stated that by November the virus research unit at M.R.D. would be bigger than at Camp Detrick.

In Washington the situation was more satisfactory. The Defence Department’s new policy was to assess the value of BW rather than to concentrate on Weapon development. Mr. Wilson, the Secretary of Defence, would control demands placed by the Services. Whilst this high level policy was an improvement, the staff at Detrick to carry it out had been greatly reduced.

DR. CAWOOD confirmed Dr. Henderson’s remarks. He considered the situation was unstable. The scientific staff was under a Colonel in whom they did not have confidence. [This was Colonel John J. Hayes; see below - JK] DR. CAWOOD said that he had met General Creasy, the Chief Chemical Officer, and was most impressed by him. DR. CAWOOD stated that the U.S. authorities were taking the reassessment of BW very seriously. A working party had been formed under the code name of “Exercise St. Joe.” The party contained Service respresentatives and was to report by mid-1955 to a committee under the Chairmanship of Mr. Merck. He thought that they might not get a very firm answer by that time. DR. CAWOOD believed that resignations of staff would continue. Dr. [Leroy] Fothergill had stated that Pine Bluff was to change over to the production of anthrax by 1955. DR. HENDERSON, however, said that he thought it was Washington policy not to change over. The plant at Dugway was producing Br. suis and would continue to do so.

THE CHAIRMAN thought that Dr. Henderson’s and Dr. Cawood’s reports confirmed our fears. The conditions at Detrick were very unsettling for research workers.

SIR PAUL FILDES said that what he had heard confirmed his opinion that the Americans were at present of little value as collaborators.

PROFESSOR WILSON SMITH asked how Dr. Fothergill’s position was altered. DR. HENDERSON informed him that Dr. Fothergill, who had been Director of the Chemical Corps Biological Laboratories at Detrick, was now technical adviser to Colonel [John J.] Hayes. Dr. [John] Schwab was now the Director responsible to Colonel Hayes.

In reply to Lord Stamp, DR. HENDERSON said that the Americans were awaiting the results of our trials in the Bahamas with great interest.

The trials in the Bahamas was a reference to Project Ozone. As for Col. Hayes, a 2004 Washington Post obituary for John J. Hayes stated, “His postwar assignments included tenure as comptroller of the Chemical Corps in Washington and commander of Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas. After a series of other assignments and a reorganization of the Chemical Corps, he served in the early 1960s as deputy commander of the Chemical Corps Research and Development Command in Washington. Later in the 1960s, he was a senior logistics adviser to the Army of the Republic of Korea.”

Final thoughts

In summary, quoting Balmer (pg. 185), “the state of US biological warfare research and policy was never entirely absent from ongoing discussions among British advisors and policy-makers about the future of germ warfare.” Though British work on BW preceded that of the U.S., the latter quickly superseded the efforts of the British. By the mid-1950s, the UK military establishment was deprioritizing biological and chemical weapons, as it fixated upon its own nuclear weapons program. The British scientific and military advocates of BW managed to keep some funding alive into the 1960s, pushing its necessity as a “defensive” matter, but governmental enthusiasm for the project kept dwindling.

Research into “defense” against use of biological weapons by an enemy long had meant, among other measures, utilizing offensive BW in retaliation from enemy germ war attack or sabotage. Even as early as 1942, according to a Chemical Corps “Historical Section” report, U.S. scientists in the WBC Committee, “charged with exploration of the entire field of biological warfare,” had “recommended that steps be taken to formulate defensive measures and procedures for retaliation.”

The scientists spelled out their reasoning: “Only by making intensive preparations [for attack] ourselves might the likelihood of its initiation by the enemy be reduced, out of fear of retaliation and subsequent infection of his own troops and country.” (History of the Chemical Warfare Service in World War II. Biological Warfare Research in the United States, Volume 2, by RC Cochrane, 1947; PDF, pgs. 34-35.]

Post-WWII, after a brief period of demobilization, the U.S. BW program had moved ahead, reconsolidating itself after the hiccups experienced at the close of the Korean War. In 1969, Richard Nixon famously discontinued the U.S. BW program, though work done on “defensive” measures were to continue. The degree to which the U.S. abandoned its program, if it ever did, is a matter of some dispute, and potentially of some urgency.

The import of the controversy presented in this article is to highlight how the U.S. biological warfare program responded to its setbacks operationally during the Korean War. It’s unlikely it was all a negative experience, from the U.S. perspective, but a complete analysis of the Korean War BW trials and field operations remains as secret as the program itself. Even so, in the controversy and “demoralisation” that impacted the Camp Detrick and associated BW programs in 1953-54, we can see the faint outlines of the full controversy that the inadequacies of the U.S. BW campaign in Korea presented for the U.S. defense establishment.

Footnotes

[1] Stubblefield’s “A Resume of the Biological Warfare Effort” is dated March 21, 1958. Copies reside at both the National Security Archive, Georgetown University, Washington, DC: Chemical + Biological Collection; and at the Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, York University, Ontario, Canada in the Endicott fonds, F0667.

When this article was originally published, I wrote, “I do not currently have permission to reproduce this document, but if I obtain such permission in the future, I will update this article.” It has since been brought to my attention that the document was uploaded to the Internet Archive by someone in February 2022. Here is the link to Stubblefield’s previously classified history, which can also be downloaded. I’d note that the document shows this copy originated at the Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections at York University, and any further copying or distribution of this article may go against the agreements by which this document was originally released. But the upload is there, and it would be remiss of me not to note it.

[2] The differences between selecting either anthrax or Brucella suis for a munitions BW agent had important policy and military consequences. Anthrax was a potentially fatal disease, particularly when inhaled. Brucella suis was considered a seriously incapacitating agent, but not necessarily a fatal one. Neither disease was considered highly infectious via human contact, while both were known to be fatal to animals.