Suppressed for Decades: FBI Reports Suggest Japanese WW2 Balloon Attacks on U.S. & Canada Included Biological Agents

Despite denials going back to 1945, new information reveals "several" WW2 Japanese "Fu-Go" balloons contained anthrax, while others were suspected of carrying bubonic plague, FBI documents attest

Two FBI reports, one of them fully declassified only this year, describe the likely, if limited, use of biological agents, in particular bubonic plague and anthrax, as part of a large-scale balloon, or “Fu-Go,” barrage launched by Imperial Japan on the United States and Canada in late 1944 and the first four months of 1945.

The most damning of the two reports was a July 6, 1945 FBI memorandum that memorialized a report from a Special Agent in Charge at the Norfolk FBI office who was briefed by a military official at Langley Air Force Base. Addressed to the Chief of the FBI’s Domestic Intelligence Division, Daniel M. Ladd, the memo stated, “recently several Japanese balloons were found in [North and South Dakota, and Nebraska] which were determined to have been carrying bacteria” (bold added for emphasis). The identity of the memo’s author is redacted.

A separate FBI memo dated May 11, 1950, from the Office of the Director of the FBI, relied on expert opinions in citing unusual outbreaks of bubonic plague in certain areas where the World War II Japanese balloons had landed in New Mexico and Alberta, Canada. The experts believed the outbreaks were likely due to the balloon landings.

The existence of Japanese balloon landings in New Mexico has not been reported publicly before, and some of these had come quite close to U.S. nuclear facilities. The 1950 memo was copied to the directors of the CIA, Naval Intelligence, and the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, as well as to the Acting Director of the Security Division at the Atomic Energy Commission.

This new evidence significantly challenges our understanding of a little-known but important episode in World War II. If this new historical evidence holds up, it means that Japan, the United States, and Canada, have hidden evidence of a germ warfare attack against the North American mainland for nearly eighty years.

Additionally, the technology for the Fu-Go balloons was studied and helped to inform the U.S.’s own efforts to create in the early 1950s the secretive E77 balloon bomb, which carried a biological agents payload. (A follow-up article looks in some depth at the U.S. balloon bomb.)

Japan’s Fu-Go Bomb Attack on North America

In November 1944, though possibly even earlier, after a series of setbacks in their war with the United States, Japan’s military began lofting thousands of balloons more than 30,000 feet (10,000 meters) into the jet stream to be carried by prevailing winds to the North American continent. The balloons carried some combination of incendiary devices and high-explosive antipersonnel bombs, as well as devices for self-destruction. The intent appears to have been to cause fires where they landed, and spread panic among the U.S. and Canadian populations. It was also greatly feared at the time that they might carry biological weapons (BW) aimed primarily at U.S. livestock and agriculture.

While the balloon bombing campaign didn’t begin until November 1944, the origins of Japan’s secret “Fu-go” balloon project went back to September 1942, when the Science Research Center at the Japanese Army’s Noborito Research Institute, located in Kawasaki’s Tama Ward, began working on the project of a transoceanic air attack on the North American continent. The premise for the balloon assault rested upon on a pioneering study by Japanese meteorologists on the nature and patterns of the jet stream.

The bombs carried by the balloons could produce notable explosions. One bomb was deliberately set off by an Army Intelligence officer in Rapid City, South Dakota. It “tore a hole in the ground three feet deep and five feet in diameter,” according to an account published by the South Dakota State Historical Society (pg. 106).

The Japanese balloon episode from World War II was recalled in a number of articles following the media frenzy surrounding a wayward Chinese balloon discovered floating over the U.S. in January-February 2023. This balloon, shot down by a U.S. F-22 fighter jet, was not however, as feared, collecting intelligence over the United States. It seems likely that China’s balloon was as Chinese authorities described it, a research or weather balloon blown off course by storms. But why the U.S. panic? Perhaps the U.S. response stemmed from secret knowledge of what a balloon attack could portend.

A May 5, 2023 Time Magazine article took the opportunity of the controversy over the Chinese balloon to revisit the old episode of the Japanese WWII balloon barrage. In an interview with Japanese balloon expert Ross Coen, the article described both the U.S. government’s fear that the World War II-era balloons could carry a payload of infectious biological agents, and the widely accepted finding that allegedly, despite such fears, none of the balloons were found to contain any weaponized pathogens.

Coen, who wrote the 2014 book, Fu-go The Curious History of Japan’s Balloon Bomb Attack on America (University of Nebraska Press), told Time:

“From the perspective of the War Department and Army intelligence, the thing that they feared most was biological warfare. They inspected all balloons for any presence of biological agents, something that might spread disease among humans or livestock. Ultimately there never was any biological component to the balloons.”

In his book, Coen summarized the extent of Japan’s balloon attacks:

“… as many as 630 balloons—7 percent of 9,000 launched—may have landed in North America between November 1944 and April 1945. With the number of confirmed landings standing at just over 300, it seems probable that a number of balloons, at least one or dozens or possibly hundreds, await discovery.” (Coen, Ross. Fu-go (p. 199). Kindle Edition.)

The purported fact that the balloons lacked anything that would mark them as biological agent delivery devices was repeated in sundry scholarly examinations of the subject, going all the way back to U.S. Air Force Major Robert Mikesh’s 1973 Smithsonian Press booklet, Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America.

Mikesh stated that he had met with sundry Japanese officials, including “many of those having firsthand knowledge of the balloon program” (pg. v). He concluded in his monograph that in regards to the threat of BW delivery via the balloons, though such use was “possible, the Japanese did not consider this aspect” (pg. 3).

When considering Japanese testimony, it seems important to mention that all records inside Japan relating to their secret balloon program were destroyed at the end of World War II.

The contemporaneous examination of the Japanese balloons was shrouded in a veil of secrecy and censorship. As early as January 1945, the government imposed a “voluntary” program of media censorship concerning the balloons. Robert Mikesh’s monograph quoted an April 1945 “strictly confidential note to editors and broadcasters”:

“Cooperation from the press and radio under this request has been excellent despite the fact that Japanese free balloons are reaching the United States, Canada, and Mexico in increasing numbers.... There is no question that your refusal to publish or broadcast information about these balloons has baffled the Japanese, annoyed and hindered them, and has been an important contribution to security.” (pg. 27)

What makes any on-going secrecy into the 21st century surrounding the presence of biological agents as part of the Japanese balloon attacks especially surprising is that it involved a serious use of weapons of mass destruction — biological weapons — against the U.S. mainland. Moreover, it was not Japan’s only planned use of BW against the continental U.S. The following article will present in some detail the evidence behind these new revelations.

Anthrax mixed with balloon gas

The FBI memo to Daniel Ladd was declassified in 2004 but was been otherwise unnoticed until discovered by this author. It is reproduced here:

The bacteria, described as coming from balloons that landed in the Dakotas and Nebraska, were identified as anthrax. The pathogen was discovered in the gas (mostly hydrogen) that inflated the massive paper-laminated balloons. The purveyor of this new information was the Special Agent in Charge (SAC) of the FBI’s Norfolk Field Division (probably SAC Robert Hicks), who had reported all this information to the unknown FBI author of the memo.

According to an FBI Field Office history of the Norfolk division, Hicks was special agent in charge from 1944-1945. The Norfolk field office was opened on December 15, 1941, approximately one week after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

According to the FBI history, “Given the Bureau’s central role in homeland security during the war and the presence of the Hampton Roads naval facility in the Norfolk Division, the new office initially concentrated on national security issues.” This included “countering sabotage and espionage.”

The circumstances of the FBI’s extraordinary memo to Ladd are as follows. On Thursday, June 28, 1945, Norfolk’s SAC (probably Hicks) attended a Weekly Intelligence Conference. One guest brought to this meeting was from a unit within the U.S. Army Air Forces at Langley Field, Virginia. Because of redactions, it’s not clear who invited this official to the meeting.

The identity of the Langley AFB official has been redacted by the government. But the identification of the source as someone who was “until recently… assigned to handling investigations concerning the landing of Japanese balloons in the states of North and South Dakota, and Nebraska,” strongly suggests the informant for the BW revelation was Army Intelligence Major Charles D. Frierson, Jr., as this memoir attests (p. 738-739).

Copies of the memo to Ladd were also sent to the FBI’s Assistant Director at the time, E.A. Tamm, and to the head of the FBI’s crime laboratory, Edward Coffey, and a third recipient whose identity has been redacted.

Coffey also happened to be a member of the Bacterial Warfare Committee at the U.S. government’s World War II biowarfare agency, the War Research Service. According to a November 30, 1942 FBI memo, Coffey was well-connected in U.S. intelligence circles, as he also served on the government’s Joint Cryptanalysis Committee, and the Special Committee on Truth Serum, formed “at the instigation of the MIB [Military Intelligence Board] of the Army” (PDF pg. 137). By April 1944, the Truth Serum committee had been taken over by the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS.

The memo’s author quoted from the SAC’s report about the meeting with the Army official. Noting that he had been told that Anthrax spores had been included in the hydrogen gas that lifted the balloon, the SAC described the significance of the finding:

“I was told that such bacteria mainly affects cattle. When the bacteria lands on wheat or other types of farm land where food is being raised for the cattle, the bacteria remain in the food when it is eaten by the cattle, and upon human consumption of the milk or meat, the bacteria can be passed on.”

The SAC further explained he was informed that the Army was “not greatly concerned over the number of such balloons which have been located, but that it does show a different trend in the Japanese attack….” Earlier examinations of the balloons had heretofore only found they carried “small bombs.”

The FBI’s Army informant was not alone in his lack of concern over the potential impact of the balloons using bioagents. A U.S. Navy "Technical Air Intelligence Center Report #41" from May 1945 concluded that while use of "insect pests or disease germs" in the balloons were a possibility, they concluded such an attack would be “Of doubtful effectiveness.” (The quoted material in this paragraph is from the "Japanese World War II Balloon Bombs Collection", Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Archives, Elizabeth C. Borja, 2018.)

Another reason the Army official and/or other bioweapons experts may not have been too concerned about balloons with anthrax was because existing cattle vaccination programs against anthrax had been very successful.

As a January 26, 1946 article in the Sioux Falls Argus-Leader put it, “There were only 14 herds of cattle quarantined for anthrax in South Dakota, Nebraska and Iowa in 1945, which is probably the lowest nunmber of cases of this disease in the past 20 years. Continued vaccination of cattle in bad anthrax areas each spring and prompt quarantines of all outbreaks are reducing the disease. The control campaign organized in 1938 is effective." A June 1953 article in Public Health Reports examining outbreaks of anthrax in the U.S. from 1945 to 1951 also shows very few outbreaks in this midwest region.

[Addendum, added April 3, 2024: Since writing this article, it has come to my attention that a 1947 Chemical Corps in-house history of the Chemical Warfare Service during World War II, “Biological Warfare Research in the United States,” stated (PDF, pg. 527):

The Japanese balloon was well-adapted to spread biological warfare agents, particularly for serious epidemics of livestock. The balloon incidents prove that the U.S. and Canada are open to this form of attack from the Asiatic mainland.

It begs the question as to what made the balloon so “well-adapted” for this purpose, as seen from the perspective of post-war analyses.]

Whatever the danger involved, including potential public panic should news of the presence of BW pathogens leak out, the FBI memo to Ladd was not meant to be have wide distribution. Its footer declared (in all caps):

“THIS MEMORANDUM IS FOR ADMINISTRATIVE PURPOSES

TO BE DESTROYED AFTER ACTION IS TAKEN AND NOT SENT TO FILES”

As will be shown, any cover-up of the apparent use of Japanese biological agents in attacks on the United States is consistent with the decades-long cover-up the U.S. organized around the activities of Japan’s biological warfare units – chief among them Unit 731. Not only did the U.S. help cover up the existence of Japan’s World War II BW efforts, it engaged in a clandestine collaboration with the personnel of these units and shielded them from war crimes prosecution. Like with the data from the Japanese balloon examinations, the information was kept tightly controlled by intelligence agencies.

“War Balloons Over the Prairie”

The fact that gas from downed Japanese balloons was examined by military and/or FBI personnel is corroborated by a 1979 report by University of Missouri historian Lawrence H. Larsen. Published by the South Dakota State Historical Society, Larsen’s essay describes a Japanese balloon that landed at Cheyenne Indian Reservation on March 20, 1945, less than four months before the memo to Ladd. Still partially afloat, the balloon was towed to a nearby ranch, where the next day it was examined by Range Supervisor John P. Drissen.

The March 20 balloon sighting is not listed in the compilations of known sightings included in all of the three major monographs written about the Japanese balloon barrage campaign: Robert Mikesh’s 1973 monograph for the Smithsonian Institute; Bert Webber’s 1975 book, Retaliation: Japanese Attacks and Allied Countermeasures on the Pacific Coast in World War II (University of Oregon Press — see especially chapters 9-11); or Ross Coen’s more recent investigation, referenced above. An October 1949 Canadian Army report, The Japanese Balloon Enterprise Against North America, noted there were four balloon sightings in South Dakota in March 1945, but no specific dates were recorded.

Larsen’s account mentioned eight different balloon sightings in South Dakota in March 1945, three more than Mikesh-Webber-Coen studies claimed, and four more than the Canadian Army monograph. The Cheyenne Indian River Reservation balloon was one of the three sightings overlooked by the other U.S. studies. An August 20, 1945 article in the Rapid City Journal also provides an early, if incomplete, account of Japanese balloon landings in the region.

The unreliability of the total amount of balloon landings is not a surprise to any historian of these events, as the extreme secrecy by both U.S. and Canadian governments put upon the balloon sightings and discoveries, and the fact that many hundreds of balloons sent to North America were never accounted for, has meant that no one who has studied this subject feels the balloon statistics we currently have are fully dependable.

Still, it is interesting that the one reliable report we have that specifically cites the presence of biological agents on any of these balloons comes from an area that has sightings that has otherwise, outside of Larsen’s study, gone unreported and unnoticed. As described below, the linkage between the presence of pathogens and the failure to document certain balloon landings will be true for balloons judged possibly linked to bubonic plague outbreaks in other regions.

In his monograph, Larsen described how the balloon was first discovered by some workers at a nearby ranch, who took the contraption back to the ranch and secured it to a post overnight. The next day, Range Supervisor John Drissen at the Cheyenne River Agency arrived on the scene, warning everyone present that they were not to publicize their discovery under penalty of “prosecution for espionage” (pg. 105).

According to Larsen’s account, Drissen examined the landing site and took photographs.

“When a rising wind tore the envelope of the balloon, he collected some of the escaping gas in two borrowed fruit jars. Soon, an agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and several army security men appeared. They took custody of the film and fruit jars, made arrangements to keep the story out of the local papers, loaded the deflated bag and the gear onto a truck, and left for their respective headquarters. The range supervisor went back to the agency, and life on the ranch returned to normal.” (pg. 105)

The appearance of both Army and FBI personnel was mandated by an agreement between the two government agencies, who were “working in close harmony” and had determined by early 1945 that all “reports of enemy missiles be made concurrently to the FBI and the Army,” according to a February 12, 1945 letter from the Office of Civil Defense to New Mexico Governor John Dempsey.

By reference to the sampling of the balloon’s gas, and the transfer of this evidence to both the FBI and Army personnel, the Cheyenne balloon is a prime candidate for the apparatus from one of the balloons that supplied evidence of the presence of anthrax. Yet, a perusal of anthrax statistics for South Dakota for the period in question shows no evidence of significant anthrax outbreak, though one such instance, however, is discussed further below. While the Ladd memo, which also specified the anthrax balloon landings had occurred also in North Dakota and Nebraska, could have been a false report, but that seems unlikely.

In relation to the incompleteness of balloon statistics, further on this article will describe an FBI report on possible bubonic plague-carrying balloons in New Mexico. The report claims a number of New Mexico balloon landings, but none of these have ever showed up in any list of balloon sightings by any authority.

As regards the capture of gas from the balloons, The National Air and Space Museum Archives’ “Japanese World War II Balloon Bombs Collection” (large PDF) has a number of reports from the War Department’s Military Intelligence Division (MID). MID General Report No. 4, dated May 1, 1945, which concerned “Japanese Free Balloons and Related Incidents,” cited an analysis of gas from one balloon recovered from Volcano, California on March 23, 1945. The captured gas from the balloon was analyzed by the Shell Development Chemical Company in Emeryville, California, and was found to contain primarily hydrogen, with 9-10% nitrogen, and a trace amount (2%) of oxygen. (PDF pg. 174-175]

The MID report on Japanese balloons for July 1, 1945 nevertheless stated, “Although there has been no evidence thus far that the balloons have been used to transport biological agents, the possibility that the balloons may be employed for this purpose still exists” [PDF pg. 198].

Even so, the vast majority of documents released to date fail to mention that bacteriological or biological substances had been discovered on any of the balloons. On this fact, most historians seem in agreement.

Yet, a recent declassified memo points to powerful circumstantial evidence consistent with the claims of the FBI Ladd memo.

Dead Rats in New Mexico

Another FBI memo was released in September 2023 to this author by the National Archives upon mandatory declassification request. It was written nearly five years after the end of the war. The May 11, 1950 memo was from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (or his office) to the Chief of the Army’s Military Intelligence Security and Training Group in Washington, D.C., with copies sent to the Director of Naval Intelligence, the Director of Special Investigations at the U.S. Air Force Inspector General Office, the Director of the CIA, and the Acting Director, Security Division, at the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).

One reason Hoover may have copied Security at the AEC was because Hoover’s memo indicated that Japan’s Fu-Go barrage included some balloons that landed in New Mexico’s Sandia Mountains, not far from secret U.S. nuclear installations. No other history of Japan’s balloon attacks has ever indicated that any balloons were sighted or landed in New Mexico.

According to Hoover, Dr. Lincoln La Paz, then Head of the Department of Mathematics and Astronomy at the University of New Mexico, suspected that an outbreak of bubonic plague in the east Sandia Mountains was related to the Japanese balloon landings towards the end of the war. LaPaz died in 1985.

During World War II, La Paz, an expert on the study of meteorites, had been Technical Director for the U.S. Second Air Force Operations Analysis Section. A webpage connected to the American Heritage Center has noted, “During this time he investigated Japanese Fu-Go balloon bombs.”

La Paz told Hoover, “two of the [plague infected] rats found on the east slope of the Sandia Mountains were only about three and a half miles from the Atomic Energy installation at Sandia Base, New Mexico.”

The infected rats, the majority of which had been found at elevations twice as high as any with plague had ever been found, were examined by New Mexico’s State Department of Public Health. The results were “unusual,” in that the rats that tested positive for plague had not done so via “an agglutination test,” a standard test for the presence of plague bacteria, indicating they might represent “some strange type of the plague.”

New strains of bacterium were routinely sought by biological warfare scientists in most countries where established BW programs existed. Scientists Theodore Rosebury and Elvin Kabat discussed the matter in a landmark article in The Journal of Immunology (Vol. 56, No. 1, May 1947), “Bacterial Warfare: A Critical Analysis of the Available Agents, Their Possible Military Applications, and the Means for Protection Against Them.” Rosebury had been the head of the air-borne infection project at Camp Detrick, Maryland during World War II.

Rosebury and Kabat wrote:

“A general principle of some potential importance concerns the selection, during the course of repeated subcultures and animal passages, of highly virulent or drug-resistant variants, or both. The possibility that strains with unusual properties might be developed by such means should be one of the problems studied by a military experimental unit.” (pg. 24-25)

In fact, the U.S.’s own biological warfare program had by late 1950 used “selective cultures” to create a strain of smallpox “against which immunization by vaccination is not effective,” as a separate FBI report of a briefing from a Chemical Corps official at Dugway Proving Ground at the time described.

The unusual nature of the plague bacteria pointed to possible BW origin. To buttress his suspicions surrounding the origin of the plague outbreak, Professor La Paz forwarded to the FBI a separate report provided to him by a Canadian official “in charge of investigating… the Japanese Paper Balloon offensive in the Edmonton [Alberta] district.”

While the Hoover memo never mentions it, an Associated Press article dated August 11, 1949 reported two very uncommon cases of bubonic plague in New Mexico in 1949. According to the AP article, “Only 21 other cases of the disease have been listed in the United States during the last 25 years.” Both of the 1949 individuals infected ultimately recovered.

Plague in Alberta, Canada

The author of the Canadian report was redacted by the National Archives, but may have been Lieutenant Commander E. L. Borradaile, Chief of Canada’s Interservice Bomb Disposal Service, a wartime agency formed to keep track of the Japanese balloon onslaught. Until it was declassified by the U.S. National Archives from this author’s request, the Canadian report on a putative link between balloon landings and bubonic plague in Alberta had never been told before.

Borradaile, or whomever wrote the Edmonton memo, described a similar set of ecological phenomenon to what La Paz had seen in the Sandia Mountains, namely the near total disappearance of expected numbers of small game (“rabbits, squirrels, small rodents, etc.”) in a region “north and west of Edmonton.” (Note the racist, pejorative terminology in the memo quoted below is kept intact here for historical reasons.)

The absence of game mentioned… may be referable to a plague among the small game of the region resulting from B.W. agents carried in by a Jap paper balloon, which to my certain knowledge came to earth in the region in which the survival test was made. This concordance came to my mind when, in the summer of 1949, an outbreak of bubonic plague carried by rats and other rodents occurred throughout Alberta, but principally in the northern part of the province, precisely the area most heavily bombarded with Jap paper balloons. In this connection, it seems worth while to point out that as far as I know, the plague had never occurred before in the area in question.

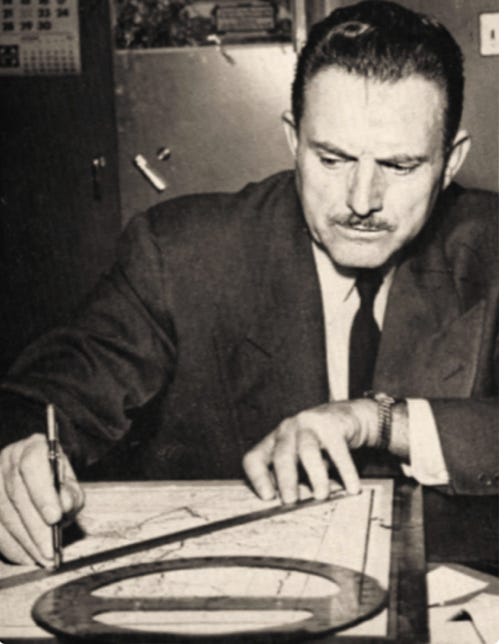

The photo below shows Lt. Cmd. Borradaile pointing to a map showing balloon landings in Western Canada. This September 1945 briefing map shows far more balloon landings in northern Alberta than any official or scholarly list of balloon landings in Alberta has ever documented, suggesting that some of these landings were purposely withheld from later public release.

Coincidentally or not, in 1950 Alberta instituted a vigorous anti-rat campaign, in an effort to stop the spread of bubonic plague in the province. The effort led to the elimination of Norway rats in that part of the country. But the area under consideration concerned a portion of the eastern Alberta border from Cold Lake, not quite half way up the long eastern side of the province, down to the border with Montana, as the yellow portion in the map below shows. The rat control zone, or the area of feared zoonotic infection, was far south and east of the northern and western regions the Canadian official (likely Borradaile) had described as possible regions of balloon-related plague outbreak.

While there were correlations between outbreaks of plague and areas of Japanese balloon penetration in both Alberta and New Mexico, the South Dakota balloon sightings also had at least one such possibly associated case, which concerned an anthrax outbreak in Haakon County, which contains a portion of Cheyenne Indian Reservation.

According to a September 18, 1947 article in the Rapid City Journal, “Anthrax Strikes in Haakon County,” the outbreak of anthrax infection among a cattle herd in Grindstone, Haakon County was the first in the area since 1936.

The article also mentions another outbreak in Lyman County, South Dakota, where no known balloon sighting or landing has ever been mentioned. Worth noting, there was another confirmed sighting of a Japanese balloon in Red Elm, South Dakota, which took place on March 30, 1945, ten days after the Cheyenne reservation incident discussed in Larsen’s essay. Red Elm lies within the boundaries of Cheyenne Indian Reservation.

Denials of presence of bioagents in Fu-Go balloons

According to the October 2020 issue of Naval History Magazine, Japan launched some 9,300 high-altitude “Fu-Go” balloons against the U.S. and Canada in the last months of 1944 and through the spring of 1945. Approximately 300 balloons, many carrying high-explosive antipersonnel and/or incendiary bombs, were known to have touched land in North America. “The balloons were blown eastward from Japan at altitudes of 30,000 to 50,000 feet at speeds of 20 to 150 knots, and reached the United States and Canada from three to five days after launching,” the essay by Norman Polman stated.

Japan’s balloon campaign was reportedly in response to the April 1942 Doolittle bombing raid on Japan, with the intent of retribution meted out upon the U.S. mainland.

In May 1945, six Oregonians out on a hike, including five children, were killed when they approached a downed balloon with unexploded ordinance. After this, the U.S. censorship program was modified such that the public was allowed to be made aware of the balloon attacks, and warned to keep clear of any discovered strange apparatuses. In Canada, the censorship directives after the Oregon deaths, while modified for greater openness, insisted that “no mention should be made of the possible use of the balloon in biological warfare” (PDF pg. 11).

The Naval History article notes that Imperial Japan’s secret biological warfare department, Unit 731, “looked into using balloons to spread germs. This was especially significant, because large balloons were developed and used to attack the United States.” Nevertheless, like all other histories on this subject over the past 79 years, this article accepted Japanese denials and stated that no biological agents were ever used in the balloon barrage.

In concluding the Japanese balloons carried no biological or germ warfare agents, Polman relied upon the 1973 account by former Air Force pilot and curator at the National Air and Space Museum, Robert Mikesh. Mikesh’s conclusion that no biological agents were present in the balloons was based on his examination of extant military documents, as well as personal interviews, including with “former Major Teiji Takada, engineer for the balloon project, who provided invaluable material and insight from his personal observations” (p. v).

In the most recent published study of Japan’s World War II balloon attacks, Fu-go: The Curious History of Japan's Balloon Bomb Attack on America (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), author Ross Coen writes, “Takada was lead technician on the balloon research program at Noborito Research Institute, and his article is an invaluable firsthand source of technical information” (p. 249).

Mikesh, Coen, and other researchers have also accepted as good coin that no evidence of the presence of biological pathogens were ever found in the balloons retrieved by U.S. or Canadian government personnel. It is worth noting that some authorities are not totally convinced. In a November 1989 study for the Center for Naval Analyses, CNA Research Specialist Adam Siegel noted that the fears surrounding possible use of biological agents in the balloon attacks may not have been so easily dismissed if researchers had realized “the fact that one major site for balloon manufacture was on Okunoshima Island, the site of the Japanese chemical warfare factory” (pg. 28).

Coen would in December 2017 publicly withdraw his earlier conclusion, based on Japanese officials “postwar denials,” that Japan “had never planned to weaponize the balloons with biological agents.” His change of mind came after reading a 1990 memoir by Noboru Kuba, an official at Japan’s Noborito Institute.

Noborito and the Decision to Use (or Not Use) Bacterial Weapons

The BW denials by Japanese scientists must be understood in the context of the wholesale destruction in the closing days of WW2 of all Japanese documentation relating to the balloon project, and other biological warfare research and operations more generally. Many of the postwar Japanese denials around biological weapons research and use have been debunked by recent scholarship.

According to 1990 memoir by Noboru Kuba, “an army veterinarian assigned to the Army Ninth Technical Research Institute, which was commonly called the Noborito Institute,” Japanese scientists did intend the Fu-Go balloons to carry biological agents, particularly rinderpest, a virus that affects cattle. But the plans were called off at the last minute. (See Amanda Kay McVety, The Rinderpest Campaigns, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 73, 75, 85.) Kuba maintained the Noborito-built balloons carried incendiary devices, self-destruct explosives, as well as radiosondes to transmit location, elevation and wind speed, but nothing more.

At the same time, the extreme sensitivity of the Noborito-engineered balloon attack program meant, according to a history by a retired CIA officer, that in summer 1945, as Imperial Japan faced defeat, all evidence pertaining to the balloon barrage over North America was to be destroyed.

On 15 August, Army Affairs Section ordered the destruction of all materials pertaining to the military’s ‘special research.’ First on the list was the Noborito Research Institute and its balloon bomb program. Also listed was the Kwantung Army’s Unit 731, which had conducted lethal experiments on captives to develop biological weapons. (Stephen C. Mercado, The Shadow Warriors of Nagano: A History of the Imperial Japanese Army’s Elite Intelligence School, Potomac Books, 2002, p. 176. Kindle Edition.)

British journalists Peter Williams and David Wallace also described in their 1989 book, Unit 731: the Japanese Army’s Secret of Secrets (Hodder and Stoughton, London) how Japan’s War Ministry in the final days of the war “set about the systematic destruction of all military documentation. A ‘Special Research Conduct Outline’ issued on August 15th by the War Ministry’s Military Affairs Section reveals that particular attention was paid to Units 731 and 100, as well as Fu (the codename for balloon bombs) and other weapons created by the ‘secret weapons’ 9th Army Technical Research Institute” at Noborito (p. 87, parenthesis in the original).

According to CIA historian Mercado’s 2002 review in the CIA house organ, Studies in Intelligence (vol. 46, no. 4), of a memoir by Ban Shigeo, a technician at the Japanese Army's 9th Technical Research Institute, Noborito, which worked on poisons and special weapons, and the Kwantung Army’s Unit 731, shared personnel. In addition, both were recruiting grounds for U.S. military and intelligence agencies at the close of World War II. Mercado stated, “One of his [Shigeo’s] book's contributions is to further tie Noborito to the Japanese Army's infamous Unit 731, which participated in biomedical research” (PDF pg. 3).

Ban himself worked for both Noborito and, on temporary assignment, for Unit 731. He subsequently “led the ‘chemical section’ of a US clandestine unit hidden within Yokosuka naval base during the Korean War, and then worked on unspecified projects inside the United States from 1955 to 1959….” His memoir has not been translated into English.

The idea of using balloons to carry infectious organisms was not new for the Japanese military. Intelligence officer Ogura Yoshikuma told a Unit 731 Exhibition that toured Japan in 1993-1994 that Unit 731 had conducted “Q” operations against the Soviets across the Manchurian border a full year or more before the United States entered the war.

We would fill balloons with nitrogen and suspend containers of bacteria below them. They would be released to drift over Soviet territory to disperse bacteria. We never found out what effects this tactic had. (Gold, Hal. Unit 731 (p. 237). Tuttle Publishing, 2011. Kindle Edition.)

Yoshikuma was not the only former Japanese official to speak about the use of balloons for biological weapons delivery. Naoji Uezono, a printer who worked for four years for Unit 731, and was privy to “all the most secret documents as he printed them,” told Williams and Wallace in 1985 that Unit 731 had put “epidemic germs… cholera and typhus” into its balloon bombs. Moreover, Uezono believed there was a balloon factory at the Mukden industrial complex associated with the prisoner of war camp there (Williams and Wallace, p. 57-8).

Williams and Wallace relied on Seiichi Morimura’s 1983 two volume book, Akuma no Hoshoku [The Devil’s Gluttony], to provide the epitaph to the balloon project. Citing Morimura, the British journalists wrote, “The balloon bombs once considered for carrying disease against the United States were never used, prohibited on technical grounds by the upper echelons of military command” (Ibid., p. 87).

The decision to forego use of the biological weapons payloads in the Fu-Go balloons reported by Morimura and Williams and Wallace is consistent with Kuba’s narrative. One difference worth mentioning is that according to Kuba, the balloons were to carry rinderpest virus, but the plan was “quashed” by General Hideki Tojo.

Interestingly, an October 25, 1946 article in The Edmonton Bulletin described the fears of both U.S. and Canadian scientists that the Japanese balloon attacks were meant to introduce rinderpest to North America, which was otherwise free from the disease. The article cited “intelligence reports,” claiming "neither American nor Canadian army chemical officers thought for a moment that they were intended foy [sic] any such futile purpose as setting forests on fire — the most prevalent lay speculation. The real purpose, they feared, was to introduce rinderpest germs on this continent.”

Tojo allegedly told Noborito staff:

“If we attack the U.S. by using balloon bombs that contain rinderpest, the U.S. will consider incinerating our rice plants in the harvest season. Therefore, the plan about the rinderpest attack is aborted” (McVety, p. 76).

Nothing is mentioned about use of cholera or typhus, much less plague and anthrax. Also, Morimura had indicated the balloon BW operations were ended “on technical grounds,” while Noborito’s Kuba claimed fear of U.S. retaliation was the reason, at least for stopping the rinderpest project.

Unfortunately, there is no access today to Uezono, who was 70 years old in 1985, and certainly has passed from the scene; or to Morimura, who died in July 2023. The latter’s book, The Devil’s Gluttony, was never translated into English either. Additionally, Noboru Kuba’s memoir has never been published, although it was apparently extensively quoted in Shigeo Ban’s book on Noborito.

The small number of scholars who have written about Kuba’s document have appeared to take it as solid evidence. But Kuba’s memoir was written in 1990, forty-five years after the events he narrated. Even if we take the story as given, that Gen. Tojo had nixed use of rinderpest as a biological weapon for use in the Fu-Go balloons, that doesn’t mean that other pathogens weren’t considered or used.

Tojo may have been correct in fearing retribution upon Japan for rinderpest attack, as there was no rinderpest in the United States, and a rinderpest outbreak would have been considered highly suspicious, and it was possible any outbreaks could be traced back to Japan’s long-distance balloons. On the other hand, plague and anthrax, not to mention cholera and typhus, were endemic to numerous areas in the United States. An outbreak inside the U.S. or Canada there could not so easily or quickly be determined as originating from foreign biological warfare attack.

In fact, it was a historical lack of plague in Alberta, Canada that led to suspicions that balloon landings there were a causal factor in a plague outbreak in the area of the balloon landings in immediate succeeding years.

During the research for this article, in June 2023 I sent a query to Japan’s embassy in Washington D.C. asking for comment on the new information about the Japanese balloons, in particular the assertions about the presence of anthrax in the 1945 FBI memo to Daniel Ladd. In December 2023, I wrote a similar request to the Public Affairs Office at Ft. Detrick. Neither responded.

Far be it from me to question the wisdom of J. Edgar Hoover, but this report lacks credibility. To limit myself to an area I am familiar with, as a medical laboratory scientist in New Mexico, plague has known to be endemic here among wild rodents, at elevations of 5000-7000 feet, since 1938.