The Cuckoo in the Ash Tree: Mikhail Sholokhov's "They Fought for Their Country" (Book Review)

A little-known but classic novel about the "bitter struggle" between Soviet forces & the advancing Nazi army explores Soviet society under the stress of WW2's fascist onslaught

When I was growing up, a staple of television was the rebroadcasting of movies about World War II. The Nazis were the reliable bad guys, whether it was Major Strasser in Casablanca, the diabolical Nazis who built the “Guns of Navarone,” or the wily German officers who sent spies into U.S. POW ranks at Stalag 17. Nazi villains, sometimes portrayed as buffoons, were everywhere, in movies, TV shows, novels, plays and comic books.

But almost none of these World War II stories so widely available to baby boomers growing up in the 1950s and 1960s concerned narratives about the actual events happening in the most fateful arena of the war, that is, on its Eastern front. It was in Soviet Russia that the Nazis met their most implacable opponent. The Nazi blitzkrieg slowed as it confronted millions of Soviet soldiers on the river plains and steppes beyond the Vistula, Dnieper, and Don rivers, and up to the banks of the Volga, where the 6th German Army met an ignominious defeat at Stalingrad.

The National World War II Museum in New Orleans describes the war in the Soviet Union and the Balkans. “The fighting on the Eastern Front was terrible and incessant, brutal beyond belief,” its website states. From 8-10 million Soviet soldiers lost their lives battling the fascist armies. Over twice that many Soviet civilians died, as the countryside was ravaged.

The mass murder of Soviet prisoners of war (POWs) held by the Germans was one of the great crimes of the war, but is rarely referenced in the West. According to Western sources, such as the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, not known as a pro-Soviet source, 3.3 million of the approximately 5.7 million Soviet POWs captured by the Germans “were dead by the end of the war. Second only to the Jews, Soviet prisoners of war were the largest group of victims of Nazi racial policy.”

So it was with some excitement that I learned that one of my favorite authors, Mikhail Sholokhov, author of And Quiet Flows the Don, one of the most popular Soviet novels ever published in the West, had written a novel about the war on the Eastern front. It was even made into a movie that had had some critical success in the West, the 1975 film, They Fought for their Country, directed by Sergey Bondarchuk, and co-written by Bondarchuk and Sholokhov himself.

I naively thought the book, with the same name as the film, would be easy to obtain, and would have a lively critical following. Instead I found the book was long out of print, and had barely attracted any reviews. While I didn’t have too much difficulty obtaining the book (I bought it used online and it took nearly three weeks to get it to me), it wasn’t exactly widely available. There was no library in Hawaii, where I live, that had the book. WorldCat showed only 51 libraries in the United States holding a copy. In comparison, Sholokhov’s Don books were available in over 3,000 libraries across the country, including in the town where I live.

Everything's complicated, Nikolai, complicated as hell.

The few online references I found to They Fought for their Country were dismissive. Sholokhov’s later work was said to be much less compelling than its Don predecessors. The book was described as unfinished. While the film was praised for portraying the Soviet experience during the war, in the West, the book seemed to have zero following. If I’m not mistaken, this review is one of only a precious few in English for this novel by the Nobel laureate Sholokhov.

An Army in Retreat

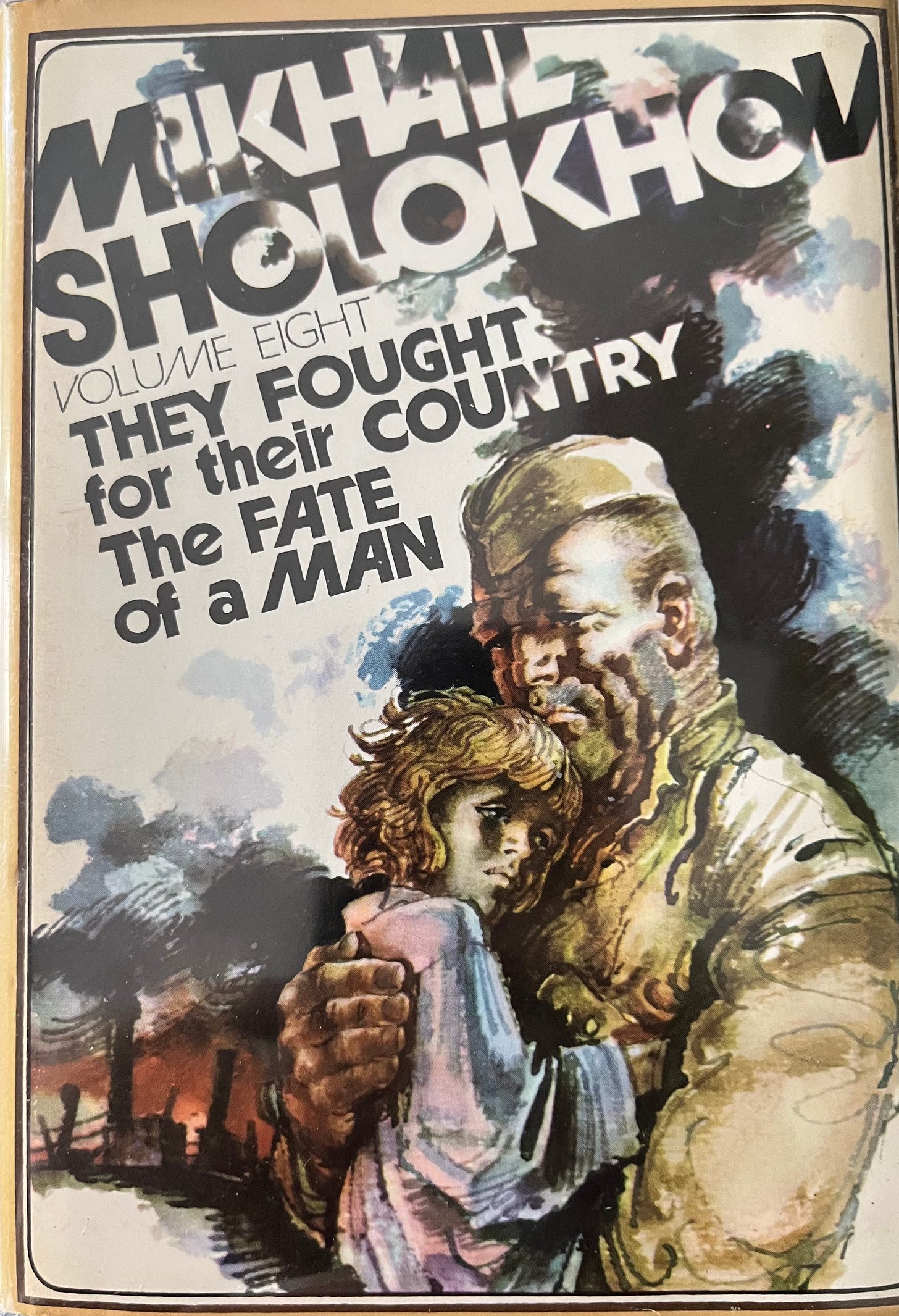

I recently read the book, which was translated by Robert Daglish and published in 1984, along with Sholokhov’s famous long short story, “The Fate of a Man,” in Vol. 8 of the Collected Works of Mikhail Sholokhov (English edition). The novel itself was first published in full in the Soviet Union in 1959, though the bulk of it was written during the war years themselves, and in the first years immediately after the Great Patriotic War (as the war is referenced in Russia).

Portions of the book had been published during the war and had been quite popular among the troops, who must have seen themselves in the portrayal of the embattled fictional soldiers. For sure, its portrayal of heroic Red Army soldiers was consistent with Soviet war propaganda needs. But the book doesn’t read like propaganda. Sholokhov the artist was writing about an army in retreat, its men broken, facing a bleak destiny, facing the implacable enemy on one hand, and a suspicious traumatized civilian population on the other.

They Fought for their Country is only “unfinished” in the sense that Sholokhov’s original conception was to write a trilogy, with the second and third volumes to cover the war from Stalingrad onwards and then the years after the war. He seems to have worked at times on these other novels, but never finished them, or abandoned them outright. The novel is much shorter than Sholokhov’s other novels, and this may have been because he meant to add more material. I tend to think it was because there was only so much he was able to portray about the war, whose intensity must have been terrific. (I’ve taken the outlines of the novel’s composition from Herman Ermolaev’s 1982 book, Mikhail Sholokhov and his Art (Princeton University Press), which appears to be out of print.)

Warning: The following review does include what could be considered “spoilers” regarding the fate of specific characters.

Whatever the vicissitudes of Sholokhov’s vision of this work, the edition of the book we have is certainly what Sholokhov intended us to read, minus any political censorship or pressures he apparently came under, especially during the early years of the Cold War. In the early 1950s, for instance, he was forced to edit out portions of the Don novels that were considered politically incorrect. Such bowdlerization was rescinded later in the decade after Stalin’s death. It’s not clear, though, how much censorship pressures played a role in the composition of They Fought for their Country.

As with his Don books, it’s surprising to read in a mainstream Soviet novel criticisms of top Soviet figures, including Stalin, not to mention discussions of the injustices surrounding the late 1930s purges and the imprisonment of thousands of innocent people in Siberian camps. Sholokhov’s aims in this regard are partly political, and partly artistic.

Sholokhov was a dedicated Communist, and barely escaped imprisonment or death during the paranoid period of the purges. He had famously refused to back down when Stalin demanded that the hero of his Don books, Grigory Melekhov, who fought for both Reds and Whites in the Russian Civil War, had to choose by the novel’s end to be a Communist. Yet against all Cold War stereotypes, it was Stalin who backed down on this point. Melekhov’s ultimate fate is instead obscure, individualistic, and even anti-heroic, yet true to his character.

Staying true to a character, even if that brings disaster for the individual involved, is an important element in all of Sholokhov’s works. The integrity of the self in a restless, violent and class-riven world is a key component of the author’s world view.

I found They Fought for their Country (sometimes translated as “They Fought for their Motherland”) a tough book to read — not because of any linguistic or artistic complexity, but because the war scenes are very intense. I had to put the book down sometimes after only a few pages because the situation the characters were in felt so stressful. I believe Sholokhov wanted his readers to feel what the war was like, especially its inexorable violence and its devastation.

Sholokhov was a war correspondent during WWII, and as a result saw the war up close. Earlier in his life, he had been a combatant during the Russian Civil War, as well as a participant in the near-civil war over collectivization of agriculture and grain requisitions during the early 1930s. His short stories, novels, and journalistic reports from the years 1919-1945 are unsparing accounts of the savagery engendered when national and class warfare erupts in a society. It is not for nothing that his work has been compared to Tolstoy’s writings on war.

But where Tolstoy remains apolitical and dismissive about the putative “gains” of war, and certainly cynical about the possibility of any battlefield “glory,” Sholokhov’s characters are passionate about their world. They are committed Communists, or in some cases, committed anti-Communists. In this book about the Red Army in battle against the Nazis, it’s impossible to be dismissive about politics when your society is targeted for genocidal destruction for its beliefs and its way of life.

“Poison should be taken only in small doses”

Despite any emotional difficulties I encountered as I made my way along the cruel trails of its war narrative, I enjoyed the book very much. It was, in fact, a revelation. The book is somewhat experimental, in that it engages in narrative dislocations and shifts that I believe are meant to parallel the experiences of an individual in the war itself. Sholokhov takes his readers on a journey into the furnace of war. The intensity of the experience is captured, for instance, in the fact that, unlike Sholokhov’s other novels, there are no chapter divisions.

The narrative is relentless. After the initial peacetime opening, the reader has few resting spots, just as a Soviet soldier fighting against the Nazi onslaught had to keep moving and keep fighting to stay alive. The reader has little time to catch his or her breath as events move along their violent path. Even so, towards the end of the book there is a comic interlude, particularly surrounding Pyotr Lopakhin’s attempt to seduce a married farmer’s wife in order to get food for the men. In addition, there are small moments of quiet personal engagement, of black humor, of quick if evanescent solidarity. An obnoxious comrade may surprisingly turn out to be a friend, or be suddenly killed, or both in quick succession. Such is war.

The bulk of the story concerns a group of soldiers who are told they must hold off the advancing Nazi army, in order to allow the bulk of the Soviet fighting force to flee across the Don River. The time is spring 1942, and the Soviet army is still in retreat. The battle of Stalingrad lies some months in the future. Much of western Russia, along with Poland, Ukraine and Byleorussia, have fallen to the Nazis. The Americans have barely entered the war. Not a single non-Soviet allied soldier has set foot on mainland Europe. Meanwhile, inside the embattled Soviet Union, the shocks of both the 1937-38 purges and then the Barbarossa disaster are still fresh in people’s minds.

The novel opens in the months prior to the war, and this first section of the book takes up nearly a quarter of the narrative. Nikolai Streltsov, senior agronomist at the Chernoyarsk Machine and Tractor Station, is dealing with the disintegration of his marriage (for reasons he, and we, don’t fully understand), when his older brother, Alexander, returns from the labor camps. The brother’s return is preceded by a lively, if unexpected (by me, anyway), discussion between Nikolai and a collectivized farm director over just how much Stalin was aware of or responsible for the crime of persecuting so many innocent men.

Pondering the question of why Alexander would be released now, the director tells Nikolai, “Well, with my simple mind I see it this way: Comrade Stalin’s eyes are gradually beginning to open.” Streltsov scoffs, “Oh, come on… Has he been ruling the country with his eyes shut?”

Alexander has spent nearly five years in the camps, after being falsely accused of political crimes. Back home at last, he and Nikolai go off to the country to fish and talk over their lives.

A bitter Alexander tells Nikolai about the circumstances of his arrest and release:

Just because they’ve let out a few people, that doesn’t mean they’ll all be set free, one after the other. The scoundrel who got us inside turned out to be a spy himself, and with a good many years of service behind him, too. And it was only when the security people had got to the bottom of things and were convinced that he had been working for German intelligence even from the time of our rapprochement with Germany, back in the days of the Rapallo treaty [1922], that they started checking up on our cases and discovered that the charges against us were pure fabrication. Then, or course, they released us, making all the right apologies and so on. We were miles away in camp by that time and it took another two years to clear up our cases satisfactorily. Everything's complicated, Nikolai, complicated as hell. Let’s leave it at that for today, or we won’t be able to think about our fishing. This poison should be taken only in small doses, or it’ll make you ill. (pgs. 58-59)

One could be excused for believing that Nikolai is the protagonist of the novel, but it doesn’t turn out that way. Nor is Alexander further developed. When the war comes, it dislocates everything. Entire families are wiped off the earth. The fate of this or that person may not be known for months, years, or perhaps forever. The unspoken question asked by the novel is how does a human being continue to exist, both physically and psychologically, among such catastrophes?

In the Trenches

The prewar world of Nikolai and his community knows war is coming, but they don’t know exactly when. They exist in an uncertain state of denial. They know Hitler and the Nazis, then in a “non-aggression” treaty with the Soviet Union, aren’t trustworthy, but they seem in denial about the terrible calamity about to befall them.

As I’ve said, the book has no chapter breaks. The narrative rushes forward and the sudden lurches of time and setting are, I believe, meant to convey to the reader the phantasmagoric experience of living in times of unexpected and precipitous trauma and upheaval, of dislocation and irremediable loss.

The narrative shifts suddenly to the retreat of the Red Army from the heavy blows dealt by the Nazi invasion. We follow Nikolai on the battlefield, holding to his position, navigating the trenches. When suddenly he is gravely injured by a bomb, we are uncertain of whether he is dead or not. The uncertainty continues until the final section of the book. The effect on the reader (or at least upon me) was one of confusion, abandonment and uncertainty. Hope seems to be a vain enterprise. People are literally dropping like flies. The future is totally unknown. The past — one’s family, one’s home, the world one previously lived in — has been destroyed. It lies in smoldering ruins.

This is how Nikolai, the character we have been following for the first 100 or so pages of the novel, disappears from the book:

Nikolai did not hear the rumble of the explosion, did not see the great mass of earth rearing up heavily beside him. A wave of hot air swept the earth off the front parapet into the trench and wrenched Nikolai’s head back with a force that snapped the chin strap and he was stunned and half choked into unconsciousness. [Later, after he recovers consciousness…. He sees] A bitter struggle was being waged all round. The few remaining men of the regiment were hanging on desperately to their positions; their fire had weakened, for few of them were fit enough to fight; on the left flank they had resorted to hand grenades; the men still alive were preparing to meet the Germans with a bayonet charge. But Nikolai, half buried in earth, lay awkwardly at the bottom of the trench, drawing air into his lungs with long sobbing breaths and shifting loose earth with his cheek every time he breathed out…. He scrambled up, looked about him with bleary eyes, and realized what was happening — the Germans were close….

He did not see Zvyagintsev and the others get to work with their bayonets as they caught the Germans on the edge of the gully; he did not see Sergeant Lyubchenko, limping far behind the others on his wounded leg… neither did he see Captain Sumskov crawl out of his shell shattered trench… Supporting himself on his left arm, the captain crawled down the slope after his men; his right arm, torn off at the shoulder by shell fragments, was dragging behind him, a ghastly deformed lump of flesh attached to his body only by a few blood-soaked shreds of tunic…. But he crawled on throwing his head back and shouting in a thin, boyishly cracked voice, “Go on, boys! On you go, boys! Give ‘em hell!”

Nikolai saw nothing and heard nothing. The first trembling star had just come out in the soft evening sky, but for him it was already the black night of long and merciful oblivion. (pgs. 106-109)

When Nikolai appears again much later in the book, it’s with little fanfare. His experience has left him deaf and dumb, and he must communicate with his fellows by written notes. He has not returned for a heroic moment. In fact, his presence could be considered a drag upon the unit. But in the circumstances, every able body is needed for the fight, and it raises his fellows’ spirits to see the young man reappear.

It’s possible that Sholokhov meant Steltsov’s deafness and muteness to be symbolic. On one hand it could represent how difficult it is to communicate the wartime experiences Sholokhov means to describe. In terms of character, it represents both Nikolai’s alienation from the world of non-combat wounded humanity. It renders him a kind of holy fool, as his wartime experience has also left him deeply traumatized and withdrawn, yet still seeking danger. His situation also provides an opportunity to display the humanity of his fellow soldiers, who watch out for and care for him.

The Role of Hatred

The individual that replaces Streltsov as main protagonist midway through the novel is Pyotr Lopakhin. Lopakhin is a real proletarian, a coal miner. He’s also older, and unlike Nikolai Streltsov, he is tough, cynical, and full of hate for the enemy. He also considers himself something of a ladies man. Lopakhin carries us through the final battles of the novel.

Sholokhov describes the world Pyotr, like so many of his comrades, lost, and the land they are fighting so hard to recover. Vengeance for what the Germans have done is a primary motivator. (Indeed, during the war, Sholokhov wrote an essay about the role of loathing the enemy, entitled “A Lesson in Hatred.”) In the book, we enter Lopakhin’s mind:

Out there in the west, in the lilac-shrouded Donside steppes lay his dead comrades; still further away in the west was his home town, his family, his father’s tiny cottage and the stunted maple-trees his father had planted, which though disfigured and grimed with coal-dust all the year round, had nevertheless been a joy to the eye when he and his father used to go off in the morning to the pits. Everything he loved had been left behind under the Germans. And once again, as so many times before in this war, Lopakhin was seized by one of those choking spasms of hatred that dry the throat before even a curse can rise from it. It happened to him sometimes in battle. But then he saw the enemy soldiers and those dark-grey tanks with the crosses on their armored sides, and he not only saw them but destroyed them. Then the hatred that clutched at his throat found an outlet in battle. (pg. 192)

Towards the end of the book, the toll of battle becomes a primary subject. Some of the soldiers suffer from “trench fever,” what we would call PTSD today. The unit has been pulled back for reassignment; its survivors are to be sent away from the front lines to recuperate. But Lopakhin and Streltsov and other want to stay and keep fighting. It’s a bitter dialogue between the soldiers. It’s clear that while those who stay and keep fighting are considered more heroic, those who seek to return and see what’s left of their family, or recover from battle have their own point of view that deserves recognition.

Not only does the soldiers’ experience deserve recognition, but so does that of the civilian population, primarily agricultural or village workers and families. Sholokhov’s sympathies extend to their experience. When the retreating Red Army passes through the farmlands of the Don basin, they are met with suspicion, even distain, by the local population. Only later does it become clear that what the civilians feel is abandonment by the army and government. It is the civilians who are helpless in the face of the racist, anti-Slav, genocidal onslaught. When they see the men fighting for their country, for the Soviet heartland, the civilians are more than ready to make their own sacrifices to aid them.

I believe one reason this novel was not embraced in the United States was because it is unashamedly pro-Soviet and pro-Communism, despite all the difficulties that followed upon 1917. While the Don novels show some sympathy for those who remained anti-Communist, the protagonists of They Fought for Their Country, and an earlier novel, Virgin Soil Unturned, are partisans for socialist revolution, and want to see it spread internationally. This is not a point of view that Western publishers were likely to embrace, then or now.

It’s worth noting that U.S. fiction about World War II men in combat — as in the works of James Jones, Norman Mailer, Douglas Valentine, and Joseph Heller — usually carries as a theme the conflict between enlisted men and the entitled and corrupt officer corps. But in Sholokhov’s WWII novel, the officers and the men fight in solidarity. The officers are respected for leading the men. They are portrayed as united in the struggle against the fascist invaders.

Life vs. Death

Sholokhov also explores what makes the soldiers push on, despite the privations and dangers and omnipresent death. Inter-relational solidarity plays a role, as does ideology, though the latter is not primarily stressed. Often the psychological stratagems are quite simple. At one point, a small group of soldiers waits in a forest as the Germans’ ranging artillery shells fall ever closer. Despite the destruction, Lopakhin observes how beautiful the forest looks after a night’s rain.

The ever-present existence of nature even among the trenches and shell-holes and “dead blasted earth” is a theme Sholokhov returns to, much as he had in the Don books when writing about the vicious battles of the Russian civil war. But the nature interludes are less in They Fought than in the Don books. I believe that’s because the war is more total here, with the constant battle of millions of men amid a devastated land. In Sholokhov’s earlier books, the forces of war and destruction as against life, sex and nature, seem equally balanced. In his book on World War II, the forces of war and destruction are clearly in the ascendant, though not yet victorious.

At one point, Lopakhin is prevented from seeing any of nature’s beauty:

But now he saw neither the breath-taking beauty or the rain-washed sky, nor the sad loveliness of the facing briar. He saw nothing but the cloud of dust flung up by the enemy vehicles as it drifted slowly westward. (pg. 192)

But the forces of life and nature are never totally defeated in a Sholokhov novel, and Lopakhin is not alone in looking to any presence of natural life as a sign of survival and the comfort of sustainable hope.

A cuckoo piped up timidly and uncertainly in the crown of a branching ash-tree. It stopped as suddenly as it had begun, as though realizing that its pensive and rather melancholy note was out of place in this wood filled with armed men and echoing with the rumble of artillery fire. (pg. 193)

One soldier, Kopytovsky, takes the cuckoo’s call as an omen that he will live out the year. Two calls of the cuckoo are superstitiously interpreted as foretelling two more years survival amid the war. Kopytovsky tells a comrade:

I’ve just been counting [cuckoo calls] to see how long I’ll live. And she goes and shuts up when she’s only called twice. Very generous of her, the long-tailed crow! But I don’t mind. That means I can go on fighting for another couple of years and not get killed. That’s fine. I don’t need any longer. The war ought to be over in two years. Bound to be.

In fact, the war would go on for another three bloody years.

A comrade asks Kopytovsky, “So you believe the cuckoo now, and after the war you’ll forget all about her?” To which Kopytovsky replies, “What did you think?… I need her comfort now, old chap. After the war I’ll get along all right without it.”

It’s too bad that Sholokhov did not complete the two successor books to They Fought for their Country. I believe if he had, he would have taken up the social and psychological issues that faced the war’s survivors. Russia, and the Soviet Union more generally, was a ruined land after the war. The Soviets were adamant they needed a buffer to protect them from future invasion from the West. Having lost approximately 25-30 million people and had hundreds of villages and dozens of cities destroyed by the Nazis, who could really blame them?

But the Soviets rejected postwar Western aid, as it came with the poison pill of economic and political control, particularly in East Europe. The Soviet Union chose to rebuild on its own, though that decision was not without internal dissension at the very top of the government. (It also meant stripping portions of East Europe of existing industrial stock, for the USSR was bereft. German prisoners were also kept for some years to provide unpaid labor to rebuild what their armies had destroyed.) Socialist planning had helped make the Soviet military into a powerhouse capable of destroying the Nazi war machine. But the stresses of rebuilding were amplified by the new Cold War, and the necessity of constructing a nuclear deterrent to Western attack.

Kopytovsky’s belief he would not need the psychological mechanisms that helped him survive once the war was won — or perhaps that he did not need the solace of the natural world to compensate for the war of annihilation — was meant, I believe to be ironic. Much would be needed by a traumatized and gravely wounded and depleted population in the years of the late 1940s and the 1950s.

In the West, there is little sympathy for what the Soviets (and Russia) endured, or of what their losses consisted. Post World War II Russia has often been portrayed over the decades as a gray place, made ugly by the inhumanity of godless Communism. But it was the civil war, famine, and then the Nazis’ genocidal invasion that made the USSR such a harsh environment after WWII.

Coda: “The Fate of a Man”

In the volume I obtained that published Sholokhov’s World War II novel, there was also printed his famous short story, “The Fate of a Man,” known in some translations as “One Man’s Destiny.” While Sholokhov never finished his planned war trilogy, this brilliant short story can be seen as an apt coda to They Fought for their Country.

In “Fate,” Sholokhov, now writing from the perspective of the war’s end, tells the story of one man’s experience of the war, of what he lost (family, home), but in this instance, he provides us a glimpse of how the war generation moved forward. The main character of “Fate” adopts a war orphan, Vanya, and takes to the road with him, “tramping the Russian land together.”

At the close of the story, which sees the man survive a Nazi concentration camp, the narrator of “Fate” watches the man and the adopted child continue on their purposeful, if seemingly aimless journey of survival:

Two orphans, two grains of sand swept into strange parts by the tremendous hurricane of war… What did the future hold for them? I wanted to believe that this Russian, this man of unbreakable will, would stick it out, and that the boy would grow at this father’s side into a man who could endure anything, overcome any obstacle if his country called upon him to do so.

I felt sad as I watched them go. Perhaps all would have been well at our parting if Vanya, after going a few paces, had not twisted round on his stumpy legs and waved to me with his little rosy hand. And suddenly a soft but taloned paw seemed to grip my heart, and I turned hastily away. No, not only in their sleep do they weep, these elderly men whose hair turned grey in the years of war. They weep in their waking hours, too. The thing is to be able to turn away in time. The main thing is not to wound a child’s heart, not to let him see the unwilling tear that burns the cheek of a man. (pg. 283)

The wartime works of Mikhail Sholokhov need to be better known. The wartime experience of Russia, and of the entire Soviet Union, needs to be better understood and appreciated in the West. As the Damocles Sword of nuclear annihilation hangs over us, especially as the United States and their allies demonize Russia and a proxy war between East and West rages in Ukraine, now more than ever does the humanity of all peoples need to be placed first and foremost before us.

This column reminded me of growing up in the 1970s, when the novels of Sven Hassel were widely available on spinner racks in local convenience stores. Though (in comparison to Sholokhov's)those books were and are of dubious artistic merit, their depiction of German grunts on the Eastern Front were eye-openers for 12-year old me, an avid reader and WWII buff.

I'd love to read this novel, but as you mention...it is basically impossible to find in English.

The full movie is on YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gOxKScK1KOU