The SKELP Directives: U.S. Secret Financing of Germ Warfare during the Korean War

Revelations about internal dissension over how U.S. germ war program unfolded; anti-crop bombs placed in UK & Libya to attack the USSR; the role of SAC in delivering chemical & biological war, & more!

Let me take this opportunity to say a big “Hello” to my new free and paid subscribers! Your interest and support is invaluable to me. I’m happy to report that in the half year or so this newsletter has been in existence, I’ve garnered over 500 subscribers! As I work away on a number of new articles, based on original research into primary source material, I’m reissuing certain past articles that I feel are especially important to the task I’ve assigned myself at Hidden Histories: to reveal war crimes otherwise unnoticed or censored, especially crimes that relate to U.S. use of torture and of biological weapons (BW).

The article below is a repost of an August 2022 article previously published at Medium.com (paywalled), and later at Counterpunch.org (free). It’s one of my longer articles, and is jam-packed with material that has never been reported before. As a summary of sorts, consider what this article will cover:

The secret funding sources used to finance secret biological and chemical warfare programs.

The use of verbal orders to hide especially sensitive orders relating to germ warfare

The use of deceptive packaging to camouflage the transport of BW, and the special measures taken to transport that material for operational use

The internal dissensions inside the Pentagon over 1) financing the BW program, and 2) choosing the biological agents and munitions to be used against the “enemy”

The particulars of Project Steelyard, the U.S. program to use anti-crop weapons against the Soviet Union

The special BW responsibilities delegated to the Air Force’s Strategic Air Command

That’s a lot of material to place in one article, and the list above does not capture all the material covered. So this is definitely an article to chew over, reread, bookmark, and consider in the light of other books or articles you may read on the subject of U.S. biological warfare, or use of Weapons of Mass Destruction more generally. It’s an essay I’m proud of, and I hope republishing it at Substack gains it a wider audience.

This latest version of the article has quietly fixed some previously overlooked typos, and added a couple of sentences here and there to better explain or contextualize the mountains of data in the article itself. The corrections and additions are very minor. The Substack version of “The SKELP Directives” is the definitive version.

The original impetus for this article came from my research into a special Pentagon Weapons System Evaluation Group (WSEG) 1952 evaluation of the U.S. BW program as it related to delivery by aircraft. That evaluation remains mostly classified. I have made a FOIA request for most of the full report. Someone beat me to it by some months. In any case, the National Archives has told me it will take literally some years to get the material! And it will be expensive to copy (many hundreds of dollars! — hint to those considering a paid subscription)! Luckily, some of the material was already declassified, and the story below contains a link to part of the WSEG report.

The WSEG material came to me around the same time as I discovered Brill Online’s special collection, “Weapons of Mass Destruction,” which had a number of declassified documents I had not encountered before. My thanks to both Brill Online and the National Archives, as well as the other researchers mentioned in the article who were kind enough to forward me documents from their own personal collection.

If you like the kind of reporting here, please consider sharing this story, following my account, subscribing (free or paid), or supporting me via the Buy Me a Coffee tip jar. But most of all, I want you to read and engage with the material I’m offering. I believe in our era of secrecy and fake truth it offers truths about our society that we must face.

The General was irritated. It was mid-January 1952, and from accounts subsequently released by China, North Korea, and international investigators, a campaign of aerial bombardment with biological weapons (BW) was taking place over both China and North Korea.

The germ weapons attacks allegedly were aimed at both military personnel and civilians, and included the dissemination of plant diseases. Now, suddenly, the bureaucrats in the Pentagon were turning off the secret money spigot for some of the most classified projects of the war!

What happened?

This essay is the first historical account of the secret funding used for the research into and production of chemical and biological weapons during the Korean War. It is based largely on declassified documents available in the U.S. National Archives, many of which are available at the “Weapons of Mass Destruction” collection at brillonline.com.

Besides clandestine forms of funding their secret weapons, this article will also look at other ways in which the BW program was kept secret, including the use of unwritten orders, the false labeling of weapons during shipment, and extraordinary security procedures taken during the movement of such materials.

The Korean War-era BW allegations have remained controversial for decades. A few years ago, this author posted online a few dozen declassified CIA communications intelligence (COMINT) reports documenting the fact that various Communist military units were indeed reporting, in encrypted dispatches with authorities and other military units, U.S. attacks by biological weapons in the early months of 1952. Units from China’s People’s Volunteer Army and the DPRK Korean People’s Army continued making such internal reports at least through the end of the year, and existing evidence argues these reports continued until nearly the armistice agreement in July 1953.

Despite such clear evidence of BW attack by U.S. forces, Western historians and commentators have ignored the CIA COMINT reports, relying on dubious documentation from “experts.” At the same time, historians have been unable to ignore the fact that the U.S. military, with assistance from the CIA, vastly accelerated its BW research program during the Korean War. Even as hundreds of anticrop biological bombs were forward positioned in England and North Africa against the USSR as early as 1951 (as will be described below), Western scholars today insist that the U.S. did not implement actual offensive BW operations during this period.

In December 1958, as part of the sedition trial of John and Sylvia Powell, who reported on U.S. use of germ warfare in China and Korea, Ft. Detrick official John L. Schwab, stated under oath in an affidavit to the federal court that from the period 1 January 1949 through 27 July 1953, “the U.S. Army had a capability to wage both chemical and biological warfare, offensively and defensively.” Schwab had been at one point Chief of Ft. Detrick’s Special Operations Division, which worked closely with CIA on concocting BW and chemical weapons for use in sabotage and assassination operations.

Schwab then added that “during the aforesaid period, the biological warfare capability was based upon resources available and retained only within the continental limits of the United States.”

As we shall see, biological munitions were indeed sent overseas as early as 1951. Declassified documents from the Department of Defense show that Schwab apparently committed perjury on this point.

In any case, if there were any covert BW campaign — one that operated on a strict need-to-know basis— we would expect its funding would also be highly classified, and directions regarding its operations deliberately muddled or unrecorded. That is exactly what we do find, as attempts were made to keep such evidence as secret as possible.

Verbal instructions only

A declassified Summary History of the U.S. Chemical Corps, dated 30 October 1951, and covering the period 25 June 1950 through 8 September 1951, revealed that under the pressures of intense warfare and U.S./UN military setbacks on the Korean peninsula, the Chemical Corps gave a “terrific push” to the development and creation of new biological and chemical agents. The relevant secret orders were delivered orally. There was no mistaking the urgency behind these orders.

According to this previously top secret internal history, the Chief Chemical Officer of the Chemical Corps at the time, Major General Anthony C. McAuliffe, “issued verbal instructions that, regardless of previous plans,” both chemical weapons (CW) and “a BW interim weapon” “were to be rushed to completion.”

The use of “verbal instuctions” implied that aspects of this program were too secret or sensitive to be written down. The operations of portions of the BW program were covert, subject to deniability by the President and other top U.S. officials. Indeed, President Truman always maintained that he never ordered their use, or a change from a supposed policy of using such weapons in retaliation only.

The use of verbal orders to maintain secrecy is hardly unknown. According to OSS documents dating from the close of World War II, verbal instructions were used to authorize field commanders to use anticrop biological weapons. Turning to a different era, the Vietnam War, Congressional investigations documented that the orders and instructions for the U.S. Air Force to secretly bomb Cambodia were delivered orally.

Similarly, Canadian scholars Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagerman documented in their 1998 book, The U.S. and Biological Warfare (University of Indiana Press, p. 11), that in 1949, “preparations… for ready implementation” of biological warfare plans were in the hands of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, bypassing the National Security Council. “These plans were so secret that they were presented orally to Secretary of Defense James V. Forrestal and Secretary of State George Marshall.” When such plans were discussed again in 1952, “it was decided that only the secretary of defense” — and not the secretary of state — would be notified.(1)

Whatever the level of secrecy involved, war plans cost money. Secret operations must leave some kind of trail. Newbie journalists are advised in their investigations to “follow the money.” And so we shall.

So let’s return to our irritated general. He was Major General Egbert G. Bullene, who left his post as head of Edgewood Arsenal to succeed McAuliffe as Chief Chemical Officer of the Chemical Corps in mid-1951. In January 1952, he and the Chemical Corps were in the very sensitive first operational stages of implementing their “stop-gap,” “interim” biological warfare plans against North Korea and China.

The plans utilized a combination of BW weapons, many apparently based upon designs from Japan’s old biowar Unit 731, which heavily relied on traditional forms of sabotage, as well as the unique use of insect vectors to deliver bacterial agents such as bubonic plague. Other BW munitions designed by Ft. Detrick and/or the U.S. Air Force, such as experimental use of aerosol dissemination of pathogens, may also have been in the mix. But suddenly the spigot of secret funding had been cut off!(2)

“Normal military channels were by-passed”

In a 17 January 1952 secret memorandum from Gen. Bullene to Secretary of the Army Frank Pace, Jr., the Chemical Corps chief complained about the sudden lower priority assigned by the Joint Chiefs of Staff to development of both Sarin nerve gas (codename GB) and to biological weaponry. The unexpected reduction in funding priority was retarding development of the Chemical Corps’ new agent production facilities for GB and BW, codenamed Projects Gibbet and Noodle, respectively.

“Priority and urgency must go hand in hand,” the general said.

“You will recall more than a year ago,” Bullene wrote to Pace (via Michael E. Kalette, special assistant for Construction at the Munitions Board, working in the office of the Undersecretary of Army for Research and Materiel), “a directive was issued to the Chief Chemical Officer… to initiate design and construction of certain highly classified projects in the field of GB and BW.”

Bullene continued:

These projects were initiated with vigorous action under a scope of highest priority and unusual administrative procedures. Normal military channels were by-passed in the interests of urgency and for other peculiar reasons known to the Secretary’s office.

Did the “other peculiar reasons” too secret to be detailed in a merely “secret” memorandum concern the use of “interim” Unit 731-style BW projects, which were utilized until the Chemical Corps more mainstream projects, such as the anti-personnel Brucella suis and anthrax bombs were ready for full-scale use?

The September 1952 report of the International Scientific Commission, headed by respected British scientist Joseph Needham documented the kinds of Unit 731 BW attacks that allegedly occurred throughout the first nine months of 1952. Looking at the use of insect vector attacks and other types of infected materials, such as chicken feathers, UK scientist Joseph Needham, and other scientists investigating the BW allegations in summer of 1952, wondered “whether the American Far Eastern Command was engaged in making use of methods essentially Japanese… questions which could hardly have been absent from the minds of members of the Commission” (pg. 12)

Needham and company could hardly have known that Fort Detrick already had sketches of biological bombs drawn from information personally obtained from Unit 731’s Shiro Ishii.

Nor could the ISC have known that U.S. Army Chemical Corps researchers believed at the time that “Insects and other arthropods act as vectors and reservoirs of some of the most promising and highest priority BW agents affecting man and animals.” The 1953 fiscal year annual report for the Chemical Corps Biological Laboratories further enthused, “Arthropods provide a tactical concept of BW agent dissemination, as they can efficiently carry agents to specific targets.” (See pg. 77 of the report, which while dated 1 July 1953, covered the period from 1 July 1952 to 30 June 1953.)

Imperial Japan’s Unit 731 and the U.S. Army’s Chemical Corps Intelligence Branch

The October 1951 “Summary History of the Chemical Corps,” quoted earlier, described in its section on “Intelligence” how the activities of its Intelligence Branch — which operated under the Plans, Training, and Intelligence division of the Chemical Corps— “were greatly increased with the advent of the conflict in Korea. The branch received a vast amount of military and technical intelligence from the Far East. Consequently it was confronted with the job of reorganizing to meet this influx and of acquiring the qualified personnel to fill new positions. At the present time these problems are not entirely solved, and temporary expedients have been adopted to meet the emergency.” [pg. 32, bold emphases added.]

Unfortunately, we still don’t know too much about how the Chemical Corps incorporated this “vast amount of military and technical intelligence,” which can only have been the data and studies provided by Japan’s Unit 731 personnel under the terms of an amnesty for war crimes secretly granted by the U.S. Most likely much of that information was destroyed, or still remains carefully guarded in the vaults where especially sensitive information remains sealed.

A portion of these materials ended up in the U.S. National Archives. In 1960, the U.S. government declassified three “key documents” from the Unit 731 materials. Titled “The Report of A” (anthrax), “The Report of G” (glanders), and “The Report of Q” (bubonic plague), the reports are hundreds of pages long. “They are available to the public at the U.S. Library of Congress.”

The 744-page Unit 731-Ft. Detrick report on “Q” (bubonic plague) rested for some years in the Technical Library at the Chemical Corps’ Dugway Proving Ground.

Much of what we do know about the postwar activities of Unit 731 and the work at Ft. Detrick during the Korean War comes from the investigations and reports of Chinese and North Korean military and scientific personnel, the limited release of certain COMINT documents by the CIA, a handful of contemporary newspaper reports, and the work of investigators from the International Association of Democratic Jurists and the International Scientific Commission.

Of much significance in this regard is a 26 June 1947 memorandum to the State, War, Navy Coordinating Committee for the Far East from two Defense Department officials, Edward Wetter with the Research and Development Board (RDB) and Dr. Henry I. Stubblefield from Ft. Detrick. The Wetter-Stubblefield memo explained that the U.S. agreement not to prosecute Ishii or other Unit 731 criminals was based on the promise “that information given by them on the Japanese BW program will be retained in intelligence channels.”

Evidently the materials became the property initially of the Intelligence Branch of the Chemical Corps, and probably the CIA, and were held closely.

As an important side note, as I pointed out in an earlier article, by Spring 1950, Wetter was serving as Deputy Executive Director of RDB’s Biological Warfare Committee. He was the contact person for all the “panels” within the Committee that were working on biological warfare, including “panels” on “Man,” “Animals,” “Crops,” and “Intelligence.” The Army representative to the RDB’s BW Committee “Panel on Crops,” i.e., for anti-crop biological warfare, was Wetter’s old colleague, Dr. Henry I. Stubblefield.

Code Name “SKELP”

Meanwhile, in January 1952, Gen. Bullene, in charge at the Chemical Corps, had his own fish to fry. In his memo to Pace, he described the special procurement procedures unique to both the Sarin and BW crash development programs:

An expediting group for priority procurement was established within the Munitions Board, and direct access to the National Production Authority was exercised. These projects were pursued under a code name of ‘SKELP’ and MPA directives issued for these projects were known as SKELP directives. These measures insured special and positive actions regarding procurement.

Hence, according to Bullene’s account, it appears that the funds for building the secret productions facilities to produce Sarin gas and agents of biological warfare were hidden in the guise of special Army military personnel directives (MPAs).

But now Bullene was flustered. Even though the “scope of priority and procedure” for procurement had continued “without hesitation or question” for over a year, suddenly in December 1951, the Munitions Board was throwing bureaucratic obstacles in the way of the Chemical Corps’ top secret projects.

Bullene described how that December the Munitions Board suddenly was requiring “a statement of priority from the Office of the Under Secretary of the Army” before proceeding with the special procurement procedures, “since the impact of other priority programs was being felt and the situation needed clarification.” When the Munitions Board did not receive such a “statement of priority or urgency,” it discontinued the SKELP priority procedures. For Bullene, the situation could not have come at a more “critical time.”

What other “priority programs” could suddenly have arisen to necessitate some kind of “clarification” at the Munitions Board (or in the office of the Under Secretary of the Army for Research and Materiel)? And why was December 1951-January 1952 such a “critical time”? Among other things, this was the period of the onset of large-scale bombing raids that allegedly used biological weapons. But there were other projects as well.

The subject line for Bullene’s memo specified that two classified programs were at stake here: the construction of a plant to develop Sarin gas (Project Gibbet) and one to produce biological weapons material, in particular, anticrop agents (Project Noodle).

Author and researcher Nicholson Baker wrote about Project Noodle in his recent book, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act (page 112):

A factory for vegetative agents, code-named NOODLE, was being built in Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas, according to a Department of Defense progress report prepared in December 1951 by Earl Stevenson of Arthur D. Little and CIA chemist Willis Gibbons. “The anti-crop program is aimed at the bread basket of the Soviet Union,” the report said. “Unfilled bombs for these agents have been produced and delivered to overseas bases. This year, increasingly significant quantities of anti-wheat and anti-rye agents have been harvested.”

According to Baker, the Gibbet (or GIBBETT) Sarin plant was built in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The Noodle plant to produce “vegetative agents,” such as wheat stem rust, was part of an anticrop program of biological warfare whose main target was the Soviet Union.

A little over a month after Bullene sent his complaint to the Department of the Army, the Joint Chiefs of Staff prepared a draft memorandum to the Chairman of the Munitions Board. Dated 25 February 1952, the draft memo, “Priority for Chemical and Biological Warfare Facilities,” proposed that both Projects Noodle and Gibbet be transferred to “the urgent ‘S’ category” for funding purposes. This policy had the backing of the Army’s Chief of Staff, who noted that previously, both Noodle and Gibbet “were given the highest authority under the name of SKELP.” (According to a 2012 Department of Defense history on DoD acquisition, [pg. 108], “S” category represented the “highest priority” of military urgency for munitions production, reserved for programs to be selected by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.)

The February 1952 JCS memo was the only other mention of SKELP directives that I have ever found in any of the extant documentation declassified to date.

However, there is very suggestive testimony by Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff for Logistics (G-4), US Army, Major General William O. Reeder. While there is a tremendous drop-off in discussion about Chemical Corps issues in the 1953 budget hearings before the Senate Subcommitee on Appropriations for the Department of Defense, as compared to earlier years, Reeder’s testimony provided an intriguing tale of bureaucratic budget reckoning with the Chemical Corps in late 1951.

Reeder told the committee, recalling the lateness of the budget process that year, “…our procurement authorities have sought by reasonable means to assure that the money was oligated with care…. because of the unfortunate wording of the House [appropriations bill], some of our funds are in jepoardy, what we call expediting production, money which goes to set up this very production base on which we must depend. Some $80 million are provided for a project of extreme importance. In this business of obligating, the Chemical Corps came to me and said, ‘We would like to go ahead and obligate this money.’ I said, ‘No; you cannot do a good job of obligating that money. You have not a good sound architect engineer’s estimate. Out of $80 million, we will give you now $20 million and hold the $60 million until you have sound figures and can make contracts that we will not be ashamed of when we are called to account for this money.” (italics added, Senate Appropriations Hearings, June 11, 1952, pg. 914)

Whether Reeder’s reference to the Chemical Corps “project of extreme importance” here is to the SKELP funding controversy or not, his testimony provides a flavor of some of the issues at that time.

“Somebody’s pet enthusiasm”

A final, suggestive explanation as to why SKELP funding of BW programs was suddenly curtailed in late 1951 appears in a 29 October 1951 memo to Air Force General Howard Bunker from William A. M. Burden, special assistant for research and development to Secretary of the Air Force Thomas Finletter, and also an “heir to the Vanderbilt fortune,” (N. Baker, Baseless, p. 173).

Burden, who had conducted his own “brief review of the present BW program,” visiting Camp Detrick (later Ft. Detrick) and Edgewood Arsenal, while also conferring with the BW Committee at the Pentagon’s Research and Development Board (RDB), was critical of the program on a number of points. His criticisms were aimed at creating a robust BW capability in the least amount of time.

Burden pointed out that some unnamed “technical consultants” at the RDB BW Committee were critical about the selection of BW agents then under development. Burden didn’t say which agents these might be, but indicated the RDB consultants claimed the choice of BW agents had been made because “a) they were easy to produce, or b) or they were somebody’s pet enthusiasm, rather than because they were the most effective agent against the type of targets on which they would actually be used.”

Could the “easy to produce” agents, the product of “somebody’s pet enthusiasm” have been a reference to the mass of infected feathers, spiders, flies, fleas and voles that in late 1951 were being planned for BW drops on North Korean and Chinese troops and villages? Whether that turns out to be the case or not, we can see that even at high organizational levels of the BW effort there was conflict over which programs and munitions were best to pursue.

Project STEELYARD and the Transport of BW Agents Overseas

The anti-crop program aimed at the Soviets was code-named STEELYARD. By December 1951, 800 biological cluster bombs were positioned outside the continental United States, meant for use against the Russians. Four hundred had been sent to RAF Lakenheath, England, and the other 400 were positioned at Wheelus Air Force Base near Tripoli, Libya. Baker noted (p. 113) that Wheelus was “temporary home of the CIA’s 580th Air Resupply and Communications Wing.”

The Air Resupply and Communications Service (ARCS) had been created by the Air Force Psychological Warfare Division, in the Pentagon’s Directorate of Plans, and was initially connected to the Military Air Transport Service (MATS).(3) My own research shows the 582nd ARCS was stationed for awhile at RAF Molesworth, only 55 miles from Lakenheath.

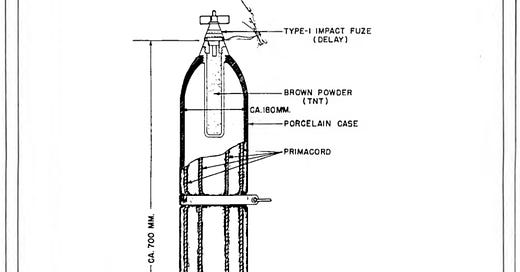

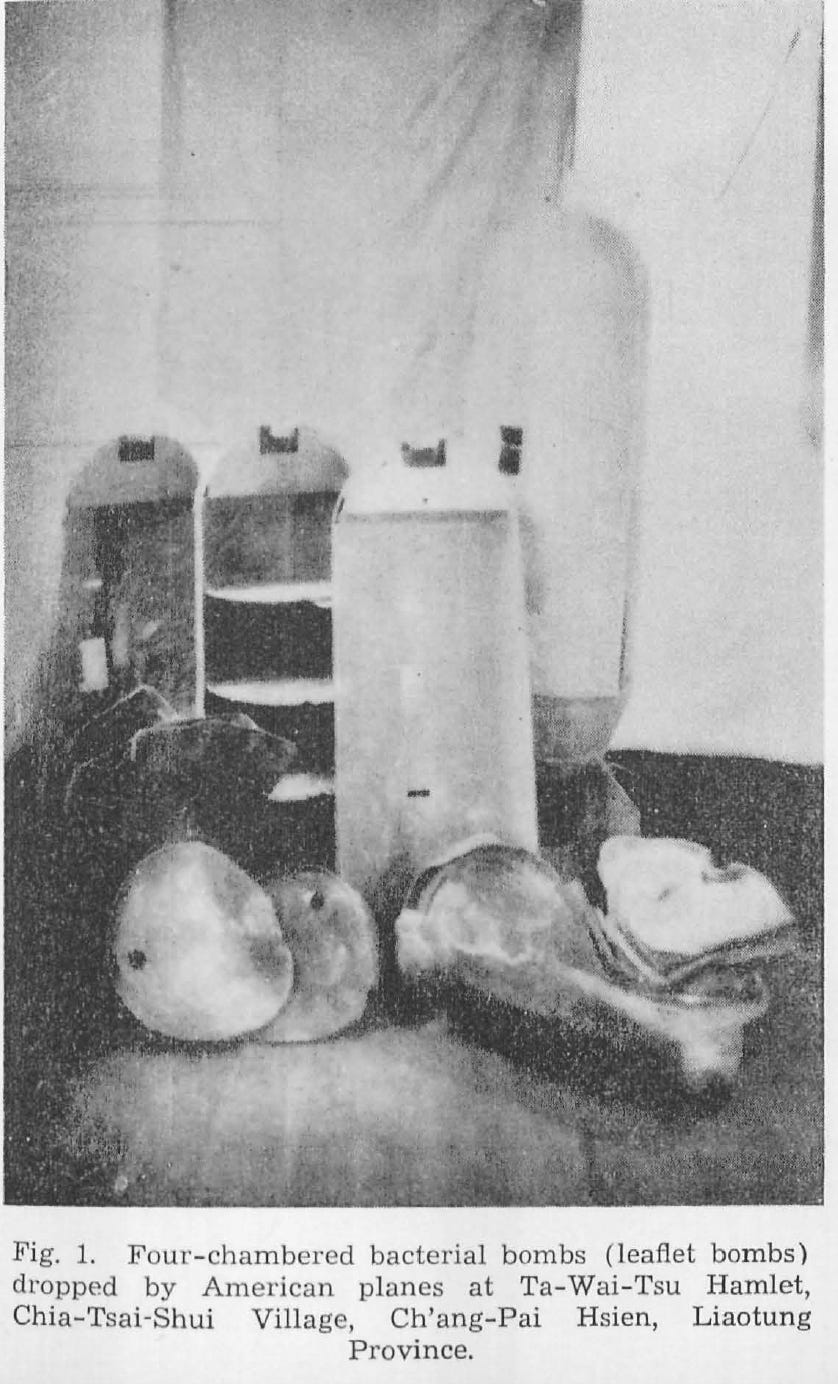

Whether or not ARCS was involved in the biological warfare program, the anticrop munitions sent abroad were modified versions of the Air Force M16 leaflet bomb, a staple of the Air Force Psychological Warfare Division. But these bombs were modified to carry infected feathers — tens of thousands of them — meant to spread disease to the wheat and rye crops of the Soviet Union. The CIA had supplied a detailed report to the Pentagon in early 1952 describing the vulnerabilities of each targeted area.

Ft. Detrick’s Special Operations and Crops divisions had earlier produced a top secret report, “Feathers as Carriers of Biological Warfare Agents.” The report explained that by December 1950 the Chemical Corps had determined that “feathers dusted with 10 per cent by weight of cereal rust spores and released from a modified [leaflet bomb] M16A1 cluster adapter at 1200 to 1800 feet above ground level will carry sufficient numbers of spores to initiate a cereal rust epidemic.” (Thanks to intrepid researcher Alice Atlas for providing this document.)

In general, anticrop biological weapons, as well as the use of chemical defoliants against crops, was more advanced at the time of the Korean War than the rest of the U.S. biowarfare program. Despite the budgetary cutbacks that had hit the military after World War II, according to historian Simon Whitby, “Between 1943 and 1950 some 12,000 chemical agents had been screened for their potential as anti-crop chemical agents.” [Whitby, S.. Biological Warfare Against Crops(Global Issues) (p. 129). Kindle Edition.] The U.S. program also benefitted from close collaboration with both British and Canadian anticrop BW programs.

According to a declassified portion of the Joint Chiefs’ Weapons System Evaluation Group’s (WSEG) July 1952 examination of “Offensive Biological Warfare Weapons Systems Employing Manned Aircraft,” the Air Force biological bombs used for Operation Steelyard were also intended to be sent to a base in French-held Morocco, as well as “a base in Cairo,” Egypt. Whether they ever were sent there or not is unknown. See pg. E-68 in document linked in the caption to the image below.(4)

In early March 1952, Air Force Mission Support Services (AFMSS) sent a Top Secret, “Operational Immediate” memo to the Commanding General of Air Materiel Command at Wright-Patterson, and a number of other very high-ranking military officials, including the Commander in Chief of U.S. Air Force (European Command) in Wiesbaden, Germany; MATS command at Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland; the Commanding General at the Air Force Air Research and Development Command in Baltimore; Gen. Egbert Bullene at the Chemical Corps; Commanding General Third Air Force, headquartered in South Ruslip, England; the Commanding Officer at Wheelus AFB, Tripoli; and the commanding general, Strategic Air Command at Offutt AFB outside Omaha, Nebraska. The subject was Operation Steelyard.

The memo reiterated the positioning of 400 biological bombs each at Lakenheath and Wheelus, and stated the need for modifications to the bombs necessary for deployment. The memo further described the plans for airlift and delivery of agent fill for the bombs (5), including time bomb fuzes and arming wire. The fill and the fuzes were to be shipped from Edgewood Arsenal. The MATS commander was ordered to prepare for the airlift.

The memo concluded, “The time period for use of these munitions is from the present thru 30 May 52. Accordingly all planning and action required must be completed as soon as possible. Implementation of delivery and airlift for (TS) Steelyard will require specific directive this hq” (parentheses in original — “TS” stands for “Top Secret”).

Hence, we see that in the middle of the Korean War, at a time when the biological warfare “experiment,” as some of the captured U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps flyers described it, was in high gear, and war with the Soviet Union still seemed possibly imminent, biological munitions meant to attack Russia were being forward deployed. It seems likely that outright war with the Soviet Union would have involved the use of biological weapons, with or without the use of nuclear bombs.

Disguising the Shipment of Biological Bombs

The secrecy that this all involved wasn’t just in the procurement details. As early as 19 September 1951, a memo from AFMSS at USAF headquarters in Washington, D.C., to the Commanding General at Air Materiel Command at Wright-Patterson airbase described the necessity of camoflaging the biological bombs to be transported overseas. The memo was copied to the Commanding General, Strategic Air Command at Offutt AFB in Omaha; Commanding General, Army Chemical Center at Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland; and the Chief of the Army Chemical Corps in D.C.

As written by “Mr. Williams” at AFMSS, the memo described the special shipping instructions for the bombs’ delivery to Lakenheath, England:

Each adapter must be inclosed in a box, and designation on each box and all shipping instructions, such as bills of lading will be marked “Hardware”… There will be no markings or other indication on boxes or bombs to indicate purpose.

Delivery to the U.S. Air Force Commanding Officer at Lakenheath was requested “as soon after 1 October 1951 as possible.”

Whether or not the anticrop weapons sent to England and Libya for possible use against the Soviet Union were ever sent further onward to Korea is a matter of speculation. There is no evidence they ever were. But as with the extraordinary SKELP directives, they point to the type of procedures the military may have used when sending non-nuclear weapons of mass destruction, such as biological weapons, to the Far East.

The idea of a transfer of BW munitions outside the European theater is not out of the question. A top secret 11 June 1951 U.S. Air Force “Staff Study” on the “BW-CW Program in USAF” aimed at fulfilling an earlier directive (JCS 1837/18) from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In this earlier directive, dated 21 February 1951 — during a period when the U.S. Army was in pell-mell retreat before Chinese forces in North Korea — the Joint Chiefs had called for “a BW-CW combat capability at the earliest possible date.”

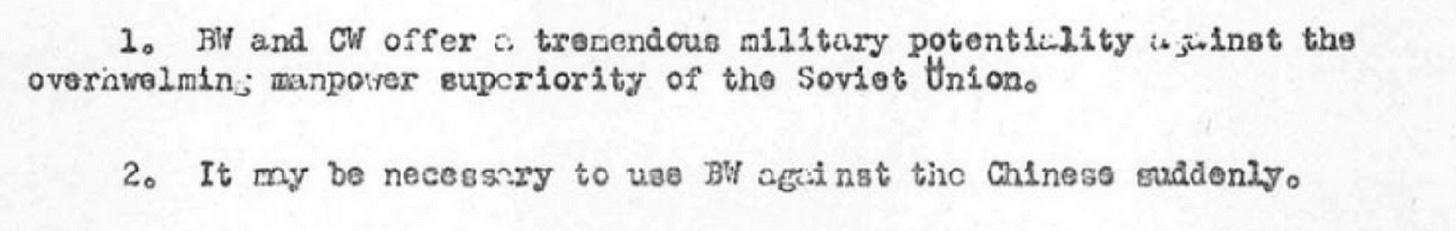

“BW and CW offer a tremendous military potentiality against the overwhelming manpower superiority of the Soviet Union,” the June 1951 Staff Study stated. The report continued, without explanation, “It may be necessary to use BW against the Chinese suddenly.” It doesn’t take much imagination to understand that the U.S. was concerned about further military successes by the Chinese People’s Volunteer forces in Korea, and was making plans to obliterate these forces.

Further pursuit of Pentagon and CIA documents may yet reveal the full parameters of the U.S. biological warfare activities during the Korean War. It’s clear that the claims of various scholars that biological weapons from Ft. Detrick never made it to the Korean War theater, including Japan, Guam, etc., are specious in that almost all of these analyses have failed to mention the implementation of operational offensive action with anticrop bioweapons. To my knowledge, there has also been no mention of the secret funding that enabled important aspects of the BW program. Nor do most of these analyses persue the hints about “stop-gap” interim BW weapons in Korea, or the similarity between the kinds of BW reported by China and North Korea and the weapons developed by Unit 731, whose designs (at the very least) were handed over to the U.S. Chemical Corps.

BW and Strategic Air Command

One totally untold story relating to U.S. plans to biological weapons concerns the special role played by the Air Force’s Strategic Air Command (SAC).

The July 1952 WSEG report, referenced above, noted, “the United States Air Force has placed the responsibility for the development of an anticrop BW delivery capability on the Strategic Air Command” (pg. E-67). This important tasking was not specifically highlighted in the original version of this article, nor does it appear to have ever been referenced in any historical account of the period. The material below should be read in light of this now documented fact.

One example of outstanding documentary evidence regarding the shipment of classified materials to the Far East in this period comes from a top secret 17 December 1952 memo from Commanding General Curtis LeMay, at Strategic Air Command, Offutt AFB to the Commanding General, 15th Air Force at March AFB. Other addressees included the Commanding General of Air Materiel Command (AMC), Wright-Patterson, and Commanding Officer, 3rd Aviation Field Depot Squadron (“3AFDS”), Andersen Air Force Base, Guam.

3AFDS had been assigned to 15th Air Force in mid-May 1951. A history of the Air Force Special Weapons Project(AFSWP) lists the 3rd AFDS as one of the components of the US Air Force’s Special Weapons Units, and trained by AFSWP.

The memo, marked “Top Secret [-] Security Information [-] Operational Immediate,” was copied to the Air Force Chief of Staff in Washington, D.C., the Commanding General of the Air Division at Travis AFB, and the commanding officers at two units at Kelly AFB in Texas. It described an airlift of “highly classified material” from Kelly to Travis AFB on 19 December 1952. From Travis, the classified materiel departed the U.S. mainland (“ZI departure point”) for Anderson AFB, Guam, and an unspecified place of arrival in Japan.

The AMC C-124 cargo plane was to be closely monitored on the trip. SAC’s commanding general advised that Travis be ready for the shipment with salvage and security teams, as well as standby aircraft and crew. Travis was to pay special attention to perimeter security for the cargo plane’s arrival.

It seems most likely the secret shipment concerned nuclear materials or munition components, given the memo’s origination from Strategic Air Command. But many people are unaware that SAC was drawn into BW plans at various points. Some of that history, as well as other relevant aspects of the BW story touched on in this article, can be found in Nicholson Baker’s excellent book, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act (see in particular discussion beginning pg. 165).

The BW-SAC connection can be seen directly in a 17 June 1952 letter from Gen. LeMay to Lt. General Thomas D. White, Deputy Chief of Staff, Operations, at the Pentagon. LeMay explained, “As you know, Strategic Air Command has been directed to achieve a one-wing CW-BW operational capability by 1 December 1952.”

LeMay told White that the plans for such a wing were simple. An SOP developed at headquarters would be sufficient “for the briefing of the few key people of the wing who need to know about the CW-BW mission.” The remainder of the letter related LeMay’s concerns about maintaining the project’s details to as few people as possible.

Was the mid-December 1952 shipment of “highly classified material” from Kelly AFB to Guam and Japan relevant to the “one wing CW-BW” project? We don’t know. But again, until full perusal of all existing documentation, and declassification of currently classified material, takes place, the primary point here will be that such overseas transfers of WMD materials did take place, and it’s not inconceivable at all that some of these materials related to biological and/or chemical weapons. Indeed, in the case of anticrop biological weapons, we know that to have been the case.

It’s the contention of this author that the revelations of a secret, outside normal channels, method of funding certain BW and CW projects, as discussed in this article, can be extrapolated to the actual biological warfare operations carried out in North Korea and China during the Korean War. Whether the latter were funded via SKELP directives, or by other equally secret means, is something that will ultimately become known as further declassifications take place, and as a new generation of historians and journalists with an appetite for truth persue these questions.

ENDNOTES

Endicott and Hagerman state, “[the] recommendation by the Army chief of staff that the secretary of defense but not the secretary of state be included in the implementation of bacteriological warfare is [in] an undated document titled ‘Deception in the Biological Warfare Field’ released with [a 1 Feb. 1952 Memorandum from the Chief of Naval Operations to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Subject: Memorandum by the Director, Joint Staff on Deception in the Biological Warfare Field].” Endicott and Hagerman, The United States and Biological Warfare, pg. 225, n. 2.

Some might contend that the secret, special funding stream for the Chemical Corps concerned ongoing projects to complete the Corps’ standard, if highly classified, biological and chemical warfare projects, such as Operation Steelyard, which is reviewed elsewhere in this article. By late 1951, it was apparent that availability of operational BW in particular was taking longer than expected to implement, given the serious military setbacks for the U.S. and allies that had occurred after China entered the war in late October 1951, which created an “emergency” situation for the U.S. military. Nicholson Baker has forwarded to me a copy of a November 1952 memorandum for the record from Col. Arthur Hoffman at the AF AFOAT BW-CW division office to Gen. James Doolittle, who was a big supporter of biological warfare, and was then special assistant to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force. Hoffman indicated that “Phase I” of the military’s Biological Warfare program needed to be extended out another six months, due to “slippage in the Chemical Corps production program.” In fact, this delay in completing Chemical Corps BW projects was why “stop-gap” measures, and an “interim BW weapon” were necessary. But it is likely not helpful for historians to draw a hard boundary between the official classified programs to develop biological weapons capacity ongoing at this time and the covert, Japanese-influenced (if not also partially staffed) programs to utilize whatever materials were at hand, including insect-vector munitions and old-fashioned sabotage tactics, in the fight with the DPRK and the PRC. While the programs were bureaucratically separate, there was significant overlap due to the fact that the actors involved — the Chemical Corps scientists and engineers, the Air Force command (particularly the Air Force’s Psychological Warfare Division, and Air Materiel Command at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base), the Research and Development Board, the Strategic Air Command, the Atomic Energy personnel, and the Munitions Board, and the CIA — were essentially the same, or drew upon the same pool of talent and expertise. The full story of the covert, Unit 731-related Korean War-era program has yet to be revealed.

See discussion on ARCS by Endicott and Hagerman, The United States and Biological Warfare, 1998, University of Indiana Press, pp. 121–123.

According to a 18 August 1952 U.S. Air Force Memorandum, “BW-CW Logistics Out of the ZI,” “seventeen areas in Africa and the Middle East and seven areas in the Atlantic” were considered for BW-CW storage as part of the logistics plan for the U.S. Air Force European Command. Presumably this included the Steelyard plans, as suggested by late historian Matthew Aid in a historiographical essay on the period at Brill Online. Aid’s essay is of some interest, but one wonders what his agenda was, or if he had not yet completed his examination of the period. For one thing, in his discussion of the SKELP directives, he indicated they covered the construction of a pilot plant for Sarin production, but was mum on the documented connection with the work on biological weapons (particularly anticrop weaponry).

As regards the availability of the BW agent fill for the anticrop bombs, see a 9 November 1951 memo from Air Force headquarters to Air Materiel Command at Wright-Patterson AFB, which indicated that at that point there was 1,200 lbs. of Wheat stem rust “available for shipment,” and 600 lbs of rye stem rust (with another 4,200 lbs. also to become available at some point). The secret 9 November memo (declassified) is included as an enclosure to a separate memorandum from USAF Col. James Totten, Chief, BW-CW Division, Office of Assistant Director for Atomic Energy to the Chief, Psychological Warfare Division, Director of Plans, Operations Division USAF, dated 5 December 1951.