Unit 731 "Completed Weapons" Ready for "Winter Use" Included Anthrax, Plague, Glanders & Cholera

U.S. use of Unit 731-derived weapons against North Korea & China in the dead of winter was denied for years as "impossible." But a U.S. Army CIC document shows cold-weather germ weapons indeed existed

I was rummaging through my files, researching a rather large article I hope to complete in the next week or two, when I was reminded of an important find I discovered during a visit Tom Powell and I made to the Hoover Institute a few years back. We were looking through the papers of historian Sheldon Harris, who wrote an important book documenting the U.S. amnesty of Japan’s WW2 biological warfare researchers at Unit 731.

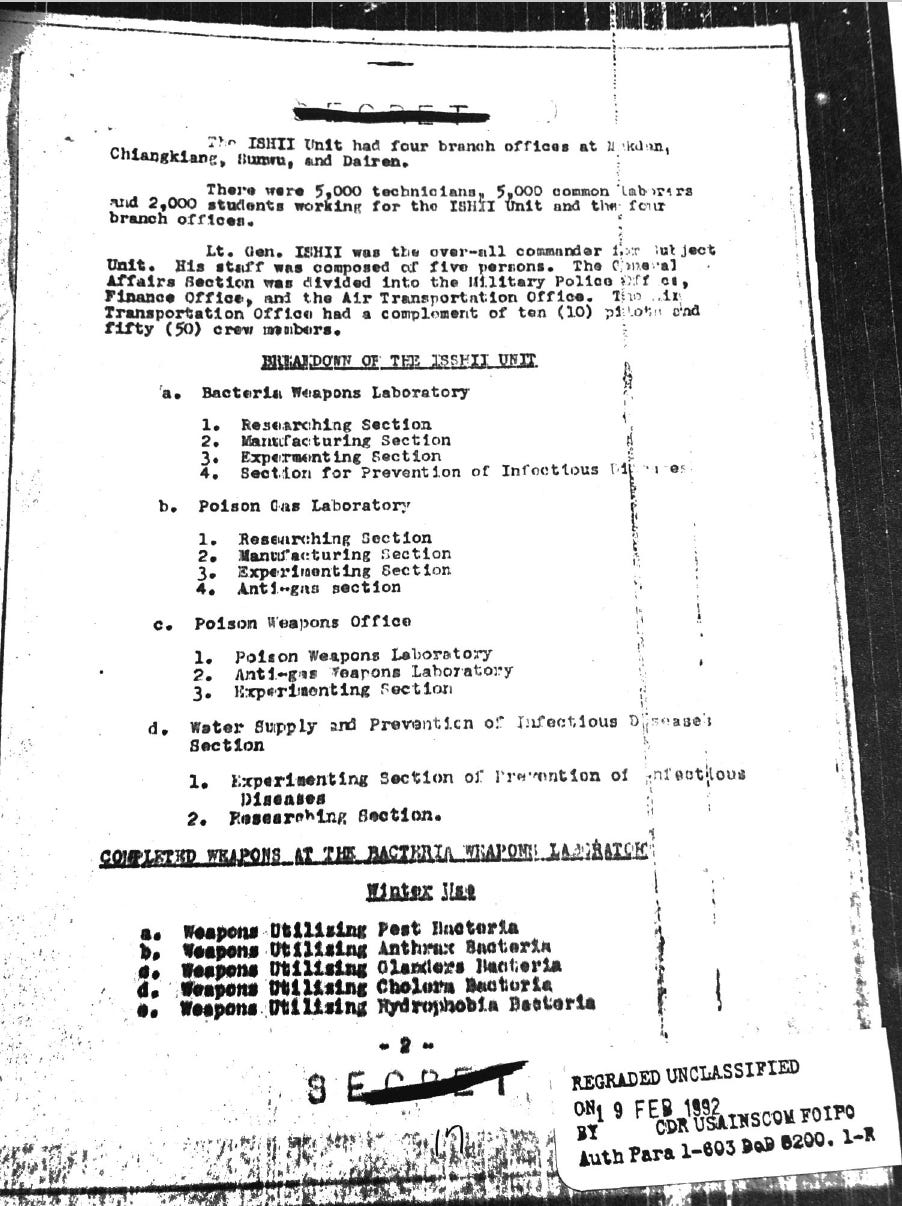

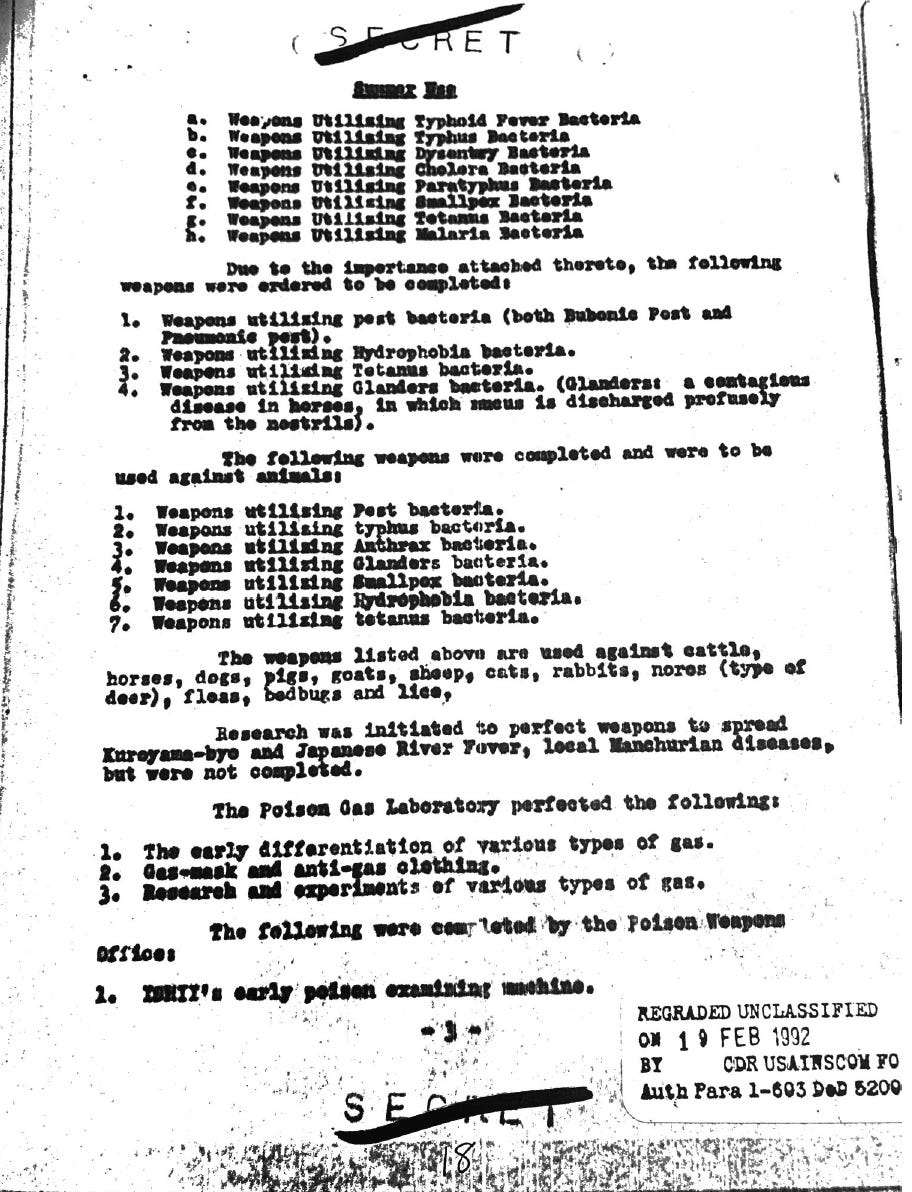

The document I wish to briefly discuss here was an April 1948 report on Unit 731 made by the 441st Counter Intelligence Corps [CIC] detachment, headquartered at General MacArthur’s General Headquarters, Far East Command in Tokyo. (The full document is reproduced at the end of this essay, and is part of the Sheldon Harris collection at The Hoover Institute.) The information appears to come from an investigation conducted by CIC, rather than a summary of other investigatory work undertaken, e.g., by U.S. Chemical Corps personnel for the biological warfare scientists back at Camp Detrick, Maryland.

This CIC document is directly related to my interest in documenting the U.S. use of biological weapons in the Korean War. From the very beginning of the scandal around the alleged winter 1952 U.S. biological weapons bombings, North Korean, Chinese and international investigators, including British scientist Joseph Needham, had considered the alleged germ war weapons to to be very suspiciously similar to those used by Japan’s Unit 731 against China in World War II.

The 1948 CIC document clearly states that Unit 731 had “completed weapons” in its biolab inventory of at least five different “bacteria weapons” ready for “Winter Use.” These included “Pest Bacteria” (a reference to Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that causes bubonic plague), as well as bacteria that causes anthrax, cholera, and glanders. The document mentions a fifth category of unspecified “Weapons Utilizing Hydrophobic Bacteria.”

Unit 731 BW personnel appear to have been ahead of their time in consideration of pathogens, as it wasn’t until the beginning of the 21st century that it was generally agreed that, as one research article put it, “the hydrophobic effect [in bacteria] is a factor in adhesion of numerous pathogens” to various hosts.

According to “Select Documents on Japanese War Crimes and Japanese Biologica Warfare, 1934-2006,” compiled for the National Archives by William H. Cunliffe, 441st CIC kept close tabs on Unit 731 ex-leader Shiro Ishii and his associates. Japanese historian Takemae Eiji described 441st CIC as part of General Headquarters’ Civil Intelligence Division. Commanded by Lieutenant Colonel W.E. Homan, CIC “provided detailed surveillance reports on rightist and ultra-nationalist groups, located suspected war criminals and drew up purge documents…. Under a top secret alert plan, ‘Tollbooth,’ CIC units drew up lists of potential ‘subversives’ to be apprehended and jailed in the event of an insurrection [in Japan].” See Takemae Eiji, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy, Continuum Press, NY 2002, pp. 167–168.

Contrary Claims

In 2016, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. published Milton Leitenberg’s monograph, “China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War.” The ostensible purpose of this monograph is to introduce us to and analyze a purported memoir by Chinese military doctor, Wu Zhili, along with some other Soviet documents meant to buttress Leitenberg’s claim that the North Korean/Chinese/Soviet claims of U.S. germ war attack during the Korean War were in actuality an elaborate hoax. I’ve dealt with Leitenberg’s claims elsewhere (see here and here).

Wu Zhili was “Director of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army Health Division during the Korean War” (Leitenberg, pg. 2). I plan to deal here at Hidden Histories soon with Wu’s purported document, which I believe is a poor example of historical evidence. In any case, I want to concentrate in this post on the claims in Leitenberg’s monograph that the cold weather in North Korea and NE China in the winter of 1951-1952 was inimical to possible biological attack, rendering the Communist claims void.

Nearly a third of Leitenberg’s CWIHP publication is given to a reprint of two articles from Hungarian journalist Tibor Méray. By contrast, the Wu Zhili posthumous essay that serves as the basis of the title of the monograph only occupies 8 pages, or less than ten percent of Leitenberg’s essay.

During the Korean War, Méray, then a loyal Communist journalist, initially reported on the germ war in Korea. Later, after the 1956 Soviet incursion into Hungary to stop a nascent political revolution there, he changed his story as he veered towards anti-communism. [1] His article, “The Truth About Germ Warfare,” was originally published in the Parisian newspaper, Franc-Tireur, in May 1957. (The other article Leitenberg reprints is a 2000 essay, “Germ Warfare: Memories and Reflections.” This paper exists in Leitenberg’s personal papers, as it was made at a presentation, but the 2016 monograph states on pg. 73, “An amended version of Tibor Méray’s reflections was published in The Korea Society Quarterly 3 (Fall 2000): 10-11, 44-45.”)

Leitenberg must believe Méray’s work to be of high importance, because he has referred to it in print more than once, and has provided much space to the Hungarian’s work ostensibly debunking the Korean War-era germ warfare charges. A full analysis of his essays on this topic remains to be done, yeoman work in critical history that awaits someone with more patience than myself.

Méray’s work is that of an impressionistic young man (Tibor was 33 when he wrote the 1957 essay). Whether or not he correctly quotes the French scientists in the work, it’s clear that the conclusions dramatically presented are just plain incorrect. That Milton Leitenberg uncritically presents this approximately sixty year old paper with no reference to its many errors marks Leitenberg as —at least as it pertains to the Korean War BW charges — a propagandist in the form of a historian.

Cold Weather Insect Vectors for Germ War Attack?

In this post, I want to look at the charges that the BW attacks were falsely made based mainly on the idea that the cold of winter, not to mention the use of insects to deliver pathogens at that time, meant there could have been no intended BW attack, because it was already known the conditions were impossible. I suppose Leitenberg wants to use Méray’s claims to buttress his claims that the germ war charges were a hoax, and the sites of infection an elaborate construction to fool outside observers.

To be fair to Méray, he appears to have relied on the “expert” opinion of scientists, but as I’ve shown recently, Western scientists can easily be recruited to serve state aims, including covering up the essentials of a BW campaign. I don’t know the motivations of the French scientists Méray consulted (assuming he quoted them accurately), so it’s best to stick to the veracity of the claims made.

In a key part of Méray’s 1957 essay, he wrote:

The reader may recall the pronouncement made by the Korean Health Minister, which stated that even though the cholera bearing insects died, the bacteria would survive, even in snow, and would become active so that an epidemic could be unleashed the following summer or autumn.

This final emergency door was barred by the formal statement made to me by Dr. Gallut, the eminent specialist on cholera [at the Pasteur Institute - JK]. “The cholera microbe is extremely fragile.” He explained. “Let loose in ‘the open’ it dies within a few hours. It fears the cold, and the temperature of ice is lethal to it. Thaw does not create more favorable environment for it either. It has generally been observed that winter puts a stop to the spread of a cholera epidemic. This phenomenon has even occurred in Egypt, a country with a warm climate, at the time of the 1947 epidemic. Naturally, it is possible to preserve cholera microbes in the cold. They are frozen by means of carbon dioxide snow at a temperature of 70° below zero. At that temperature they are dehydrated in a way and can be preserved for years in tubes.”

“Is such preservation not possible in the case which I had seen?”

“To reactivate the microbe, it must stay for twenty four hours in a culture solution at 37° above zero. To throw back into the open deep-frozen microbes would be of no use. Such an idea could not even occur to anyone calling himself a scientist.”

Thus, all the scientific and pseudo-scientific explanations which had been given me with regard to flies which were carriers of cholera germs, were refuted one by one bowed before the facts: IMPOSSIBLE TO START A BACTERIOLOGICAL ATTACK BY MEANS OF FLIES. It does not make sense to throw microbes on the ice and to say that they could be reactivated later on. [pg. 48 of the monograph; pg. 56 of the PDF linked]

Well, is the bacteria that causes cholera really that fragile?

A fact sheet on Vibrio cholerae released by the Canadian government states:

Cholera can survive in well water for 7.5 ± 1.9 days and the El Tor biotype can survive 19.3 ± 5.1 days. The bacterium can survive in a wide variety of foods and drinks for 1-14 days at room temperature and 1-35 days in an ice box. It has also been found on fomites at room temperature for 1-7 days.

That doesn’t sound “fragile” to me. But the same document also says, “Vibrio cholerae is sensitive to cold (loss of viability after a cold shock at 0ºC)” (parenthesis in original). While bacterial inactivation begins at freezing temperatures, that doesn’t mean the virus is dead. It is merely temporarily inactive.

Or is the Vibrio of cholera really made inactive by cold? According to the abstract of a June 2002 article by M.D. Johnston and M.H. Brown in the Journal of Applied Microbiology (Volume 92, Issue 6, 1 June 2002, Pages 1066–1077), “Vibrio organisms, whether culturable or in the non‐culturable form, were not inactivated by freezing to −20°C…. Freezing had no effect in reducing cell numbers.”

Another research paper [2] states that shrimp inoculated with V. cholerae cells and frozen to -200°C still had “viable cells of the test organism… stored under frozen conditions, after 36 days.”

And just because I’d like to drive a stake into Leitenberg’s mistaken citation of Tibor Méray’s claims that the “the temperature of ice is lethal to” cholera-causing bacteria, I will cite a third research paper [3], one that used human volunteers inoculated with liquid from a frozen vial containing Vibrio cholerae.

The 1998 study showed that of the forty volunteers (eight groups of five volunteers each) so inoculated, “all groups of volunteers” developed illness that “were, in general, typical of cholera…. Of the 40 volunteers, 34 (85%) developed diarrhea; the attack rates in the groups varied from 60 to 100%. Only one group among the eight had fewer than four illnesses. Of these illnesses, 16 (47%) were mild, 8 (24%) were moderate, and 10 (29%) were severe. As expected, the most prominent symptom of the illnesses was watery diarrhea, typical of cholera… most symptoms started the day after” the inoculum was administered.

The research clearly shows that cholera is not destroyed by freezing temperatures, even in some cases at temperatures as low as -200°C. Now either Dr. Gallut was mistaken, or he was lying, or Tibor Méray was mistaken in what he heard, or was lying, but the real issue isn’t even that. One must ask why in 2016, Milton Leitenberg, or the editors or peer advisers associated with his CWIHP monograph never questioned Méray’s claims. (I wrote to CWIHP in July 2022 about the need to correct errors in Milton Leitenberg’s monograph, although not on the cold issue. They never replied.)

An associated historical piece of evidence on the cold issue was described in another article I wrote recently: “It’s worth recalling that in the earlier, extensive biological warfare work of Japan’s Unit 731, they had also experimented with use of biological weapons and insects in frigid temperatures. After World War II General Douglas MacArthur sought to convince officialdom in Washington, D.C. to provide amnesty for war crimes to Shiro Ishii and the scientists of Unit 731 – so the US could use their expertise for the U.S. BW program. MacArthur had explained, ‘Ishii claims to have extensive theoretical high-level knowledge including… the use of BW in cold climates.’”

MacArthur’s claims appear to be significantly substantiated by the CIC document described in this article, and appended in full at the end of this post.

Lies and Truths About Use of Insect Vectors

Finally, there is Gallut/Méray’s claim that it would be “impossible” to use flies as the instrument of a biological attack. The claim is easily falsified by reference to the many examples of U.S. research into the use of entomological warfare.

Professor Jeffrey A. Lockwood wrote an entire book on using insects in warfare. In 2010, Oxford University Press published his book, Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War. Lockwood noted that Canada, in cooperation with the United States on matters of research into biological warfare, had by the late 1940s or early 1950s “devised a 500-pound bomb capable of delivering 200,000 infected flies to a target…” (Six-Legged Soldiers, Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition. Location 3012).

In a recent article for The Canada Files, I revealed that in December 1947, top Canadian entomologist G.H. Reed had prepared a paper for the BW Research Panel of Canada’s Defense Research Board. The paper, “The Present Position of Bacteriological Warfare - a Brief Review,” told how bombs were then being tested that used flies that had been fed “on cultures of typhoid-dysentery type bacteria,” which would then be released “from screen cages contained in aircraft bombs.”

In the same article, I described how some five years later, in a secret 1953 memo to Canada’s Minister of External Affairs, Lester Pearson, Reed said in regards to the Communists’ claims of use of insects as vectors to deliver pathogens even in winter, “The dropping of insects from the air is entirely feasible.”

To conclude, the CIC document corroborates other evidence noting the expertise of Unit 731’s ability to deliver insect-vector biological weapons attack as early as World War II. The U.S. extensively debriefed the Unit 731 scientists after the war, part of a secret amnesty agreement the U.S. made, where Japan’s BW scientists, who had helped organize BW attacks on the Chinese mainland, gave the U.S. its knowledge base and experimental materials in exchange for freedom from war crimes prosecution. They also reportedly consulted with U.S. biological warfare scientists during the years of the Korean War, although clear evidence of that is currently lacking.

When the U.S. biological warfare program was not ready to deliver antipersonnel biological munitions by late 1951 during the Korean War, the U.S. turned to “stop-gap measures” to implement BW “operational readiness” during the Korean War. The U.S. already had, by October 1950, according to a previously Top Secret history of Air Force, “seven BW agents… judged feasible for use, all of which could be produced in facilities already established or proposed.” These agents included anthrax, brucella, tularemia, plague, botulinus toxin, cereal rust spores, and chemical growth regulators. (See J. Kaye, “The Schnacke Affidavit: U.S. Admission of Offensive Germ Warfare Capability During the Korean War”, Medium.com, July 17, 2021.)

The critics of the Communist charges of U.S. operational use of biological weapons during the Korean War have always rested on the claim that such an attack was impossible, not least because of the cold weather in the first months of the attacks. The facts show otherwise, but most Western scholars either lie about this, or keep mum on the subject.

Changing minds is a difficult thing. Debunking decades of lies and suppression of the truth is even more difficult, not to mention a tedious enterprise. I hope that this article, and the work of this blog will assist future historians and journalists, as well as educate and inform today’s interested readers, with the goal as well of forestalling a future war in Asia, where the U.S. has sown so much distrust.

Endnotes:

[1] In his 2000 essay, “Germ Warfare: Memories and Reflections,” reprinted in Leitenberg’s 2016 monograph, Méray wrote: “I have to say that my belief [on the germ war charges] was shaken not by Korea but by events in Hungary. Not long after my return to Hungary I realized the extent of the crimes of Stalinism that had been committed in my country and the mass of lies that covered these crimes. At this stage simple logic led me to the history of the Korean War. I asked myself whether they had told me the truth about many things, including the germ warfare. I knew the similarity between the two regimes. The parallel caused me to be filled with doubts.” (pg. 77 or the monograph, or pg. 85 of the PDF linked).

[2] See abstract, Denilde R. Nascumento, Regiñe H.S.F. Vieira, Hauston B. Almeida, Thakor R. Patel, Sebatiao T. Iaria, “Survival of Vibrio cholerae 01 Strains in Shrimp Subjected to Freezing and Boiling,” Journal of Food Protection, Volume 61, Issue 10, October 1, 1998, Pages 1317-1320.

[3] David A. Sack, Carol O. Tacket, Mitchell B. Cohen, R. Bradley Sack, Genevieve A. Losonsky, Janet Shimko, James P. Nataro, Robert Edelman, Myron M. Levine, Ralph A. Giannella, Gilbert Schiff, Dennis Lang, “Validation of a Volunteer Model of Cholera with Frozen Bacteria as the Challenge,” Infection and Immunity, Vol. 66, No. 6, pp. 1968-1972.