U.S. Military Chiefs Gave Secret Orders to Use Germ Warfare on Japan

By July 1945, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff gave military commanders approval to use anti-crop biological weapons against Japan, including authorization for covert use by the OSS.

I originally published a less comprehensive version of the following article in May 2018. I believe the events related below speak to the mens rea of important actors in the U.S. government, who were pursuing the use of biological weapons (BW) during World War II. This evidence of intention of wrong-doing on a grand scale informs my thesis that less than seven years after the bombing of Hiroshima, the U.S. again turned to use of weapons of mass destruction by using offensive BW during the Korean War.

At the end of this article, I have included an appendix on the secret code names U.S. government researchers used to describe the different biological agents they used and worked to develop (Agent “X,” Agent “IR,” Agent “LE,” etc.). The appendix is meant to assist those who wish to read further in the literature on this subject, or wade into the documentary record, such as it is available to us. Hence, even if you don’t read through this entire article, you may wish to bookmark it or otherwise save as it as a reference.

In the closing days of World War 2, the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the offensive use of germ warfare aimed at destroying enemy crops, placing final approval for use at the discretion its top commanders in the field, according to Office of Strategic Services (OSS) documents formerly classified “Secret” and “Top Secret,” whose originals are held in the U.S. National Archives. (See “References” at close of article.)

OSS was the wartime predecessor of the CIA, responsible for organizing covert activities behind enemy lines, as well as gathering intelligence.

On August 3, 1945, three days before the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Captain Donald B. Summers of the Chemical Warfare Service, who also served as Chief of the OSS’s Special Assistants Division (SAD), sent a “Secret” memo to his boss, Lt. Colonel John M. Jeffries. Jeffries was chief of OSS’s Research and Development Branch; SAD was a subunit of the Research branch. Jeffries had replaced Stanley Lovell, who had been R&D’s first director.

According to the website of the U.S. Army Special Operations History Office, “The mission of the Research and Development (R&D) branch was to develop devices to help undercover OSS agents, enhance intelligence gathering, or to facilitate sabotage operations.” The website compared R&D to Q Branch in Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels. That would make first Lovell, and then Jeffries, the U.S. version of Q.

Besides “exploding candles” and cyanide pills, “The most critical items developed by R&D were special explosive and incendiary devices to destroy enemy equipment, vehicles, and infrastructure.” As discussed below, some of R&D’s work included devices that delivered biological agents or toxins to human beings, animals, and plants.

Summers’ memo consisted of a cover letter, and his attached monthly report for July 1945, which included sections on “General Actions and Achievements” as well as the “Difficulties” of the division. In a section on “BW,” Summers wrote (italics added for emphasis):

It is understood that the Joint Chiefs of Staff have given their approval to the use of plant BW provided the theatre commander wishes to use it. In view of this attitude this division has planned several items which can make use of the material available from Chemical Warfare Service. This would necessitate the use of a machine shop and a carpenter shop. If desired this division will proceed with such investigations. Intelligence, both defensive and offensive, is being maintained on the other phases of BW. [PDF, pg. 3]

Summers noted that if the war was not over by the end of the year, both biological and chemical weapons “might be still used” (PDF, pg. 4).

Among other items Captain Summers discussed in his report were the use of tablets that could kill or disable (“L” and “K” tablets, respectively), the use of marijuana (called “TD” in the report) in interrogations , and other intelligence technologies, such as silent weapons, secret writing, and toxic substances. The TD research had been part of a secret Truth Serum study undertaken in conjunction with the Manhattan Project, and headed by the Superintendent of St. Elizabeth’s mental hospital in Washington, D.C.

Since the war in Europe had ended in early May 1945, one can presume the “theatre commanders” with authority to use anti-crop biological weapons referred to in Summers’ memo were Pacific and Far Eastern commanders Admiral Chester Nimitz and General Douglas MacArthur, respectively.

Another mention of the order to authorize use of anti-plant biological weapons against Japan appears in an undated “Summary of Activities” for SAD, which outlined the work of the department from January 1, 1945 through August 15, 1945. (The “Summary” document probably dates from around September 1945.) Under the heading of “Intelligence” activities, the summary provided a temporal synopsis of SAD’s work, which included items relating to biological weapons (italics below added for emphasis):

3. Prepared plans for utilizing BW for OSS in case such a program was authorized.

4. Visited areas where BW research and development was being performed and maintained contact with proper personnel.

5. Prepared to use plant BW and obtained authorization for use.

Actual approval by U.S. authorities for the offensive use of any type of biological warfare has never been published by any other author that I’m aware of, with the exception recently of John Lisle in his interesting 2023 book, The Dirty Tricks Department: Stanley Lovell, the OSS, and the Masterminds of World War II Secret Warfare (see page 182).

Lisle pointed out the distaste that Admiral William Leahy, chair of the Joint Chiefs, had for biological weapons. Lisle stated that the theater commanders shared Leahy’s opposition to attacks on the enemy’s crops. (In a personal communication, Dr. Lisle told me that in his book it should have stated only that the commanders “apparently sided with Leahy” in opposition to use of BW. It’s a reasonable assumption, but we don’t really know for sure.)

At this juncture, I want to point out as important that it was the practice of the U.S. government to use oral and not written orders when it came to use of biological weapons. Most likely this was because the orders involved actions widely deemed to be illegal, or at the very least, politically and militarily of extreme sensitivity. I shall examine more around this issue further below.

Preparing for Use of Bioweapons and Chemical Defoliants

The purpose of plant biological warfare, according to a Chemical Warfare Service document written soon after the war, was “to destroy or reduce the value of crop plants.” In essence, the practice amounted to a war crime. The intent was to deny food to enemy troops, and increase hunger, if not produce famine among the population of combatant nations. Along with biological warfare against human targets, anti-crop BW was expected to sow panic and fear among the civilian population.

While it is known that the United States had by 1942 been developing a robust biological warfare capacity, no document has previously shown that any final approval for the use of any form of germ warfare had been given.

A well-researched, 2022 senior thesis by Matthew M. Chagares at Columbia University described both the extent of the production of U.S. biological agents, and the internal legal wrangling to make BW use feasible. By 1945, anthrax and botulinus produced at secret facilities in Vigo, Indiana and the Army biological and chemical weapons complex at Camp Detrick, Maryland could “fill 500,000 bombs per month.” Meanwhile, a Michigan Dow Chemical Plant was contracted “to produce 500 pounds of [the chemical herbicide] 2-4 dichlorophenoxyacetic acid per day.”

In the secret world where the military use of bacteriological or biotoxic weapons was planned, anthrax was referred to as “N.” Botulinus, a deadly neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, and known today by millions of people as “botox,” was called “X.” The various herbicides developed for mass distribution against crops were coded “LN.”

During World War 2, responsibility for the BW program was placed with the War Department. In January 1944, the Secretary of War told the Chief of Staff of the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS), which was in charge of both chemical and biological warfare due to their supposed “similarity of action,” “the time has arrived that for military reasons work should be initiated for carrying on intensively the offensive as well as the defensive side of BW in preparation for protection against attack….” (See History of the Chemical Warfare Service in WWII, Vol. II, by Rexmond C. Cochrane, Historical Section, Plans, Training and Intelligence Division, Office of Chief, Chemical Corps, November 1947, PDF pg. 79.)

According to Chagares’ thesis, in July 1944, the Joint Chiefs ended the preexisting policy that held biological weapons would be used only in retaliation of an enemy’s BW attack. “As a result, no offensive biological weapons policy was ever promulgated during World War II, leaving open the possibility of first use by the United States,” Chagares wrote. His citation to document this important change was an April 10, 1944 memo from Major General S. G. Henry to “Chief of Staff”, presumably Admiral William Leahy, titled “Biological Warfare” [NARA, RG 218, UD 92 Box 1, National Archives at College Park, MD]. I have not, as yet, examined this document myself.

Chagares also referenced a March 1945 memo from the Army’s top legal official, Major General Myron C. Cramer (Judge Advocate General) to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. The memo said, in part, “‘[t]he United States is not bound by any treaty’ prohibiting the use of biological weapons.” Chargares continued, “Although military attorneys acknowledged the Geneva Protocol of 1925, they were quick to note that the United States never ratified that treaty. [Cramer’s] opinion finally noted that even if international law prohibited using biological weapons to injure humans, there was no impediment to destroying crops and other plants.”

Other corroborative evidence of the activation of offensive use of anti-crop biological weapons at the end World War II has been difficult to come by. But there is strong circumstantial evidence available in a number of secondary sources.

By 1944, both the U.S. and the United Kingdom were working on biological agents for possible use against Germany and Japan. According to the well-regarded history by Robert Harris and Jeremy Paxman, A Higher Form of Killing: The Secret History of Chemical and Biological Warfare (2002/1982, Random House), before the end of the war the U.S. may have already used rice blast to weaken or destroy the Japanese rice harvest (see Harris and Paxman, pg. 102).

According to Sharad Chauhan’s 2004 book, Biological Weapons (APH Publishing, New Delhi), in 1945 Japan’s “rice crop was badly affected by rice blast,” though there was no proof that it was due to U.S. BW attack (see pg. 194). Still, according to a report by Liam Walsh for the Australian newspaper, The Courier Mail, “the U.S. by July 1945 had built up chemical stocks theoretically ‘sufficient to destroy one-tenth of the rice crop of Japan.’” If Japan’s rice crop suffered an epidemic of rice blast in 1945 at the exact time the U.S. was researching and stockpiling such an anti-rice crop pathogen, with consideration of using it against Japan, that would have to be considered an incredible coincidence.

Another piece of evidence is discussed in Simon M. Whitby’s 2002 book, Biological Warfare Against Crops (Global Issues Series, Macmillan Distribution Ltd). Whitby cited a reference to the shipment of anti-crop chemical agents, which at the time were grouped in the BW category, “to a location in the Pacific close to the island of Iwo Jima.”

Whitby continued, “The single reference to this claim appeared in a book by Baldwin W. Hanson who wrote in 1950 that: ‘in July and August, 1945, a shipload of U.S. biological agents for use in destruction of the Japanese rice crop was en route to the Marianas’” (pg. 123 in Whitby). The book he’s referencing is Hanson’s Great Mistakes of the War, Harper and Brothers, New York, 1950.

As Whitby discussed in his book, the question of whether then-President Truman had changed the “retaliation only” policy for use of chemical or biological weapons is a controversial one. Truman, for one, denied he ever did.

Making crop-destroying agents “as virulent as possible”

It is known that during World War 2 the U.S. had developed pathogens to be used against plants and animals. This project was discussed in the now declassified 1947 report (PDF) referenced earlier, “Biological Warfare Research in the United States.” The report stated, “Agents selected for investigation were made as virulent as possible, produced in special culture media and under optimum conditions for growth, and tested for virulence on animals or plants” (PDF pg. 26).

The Chemical Corps history also reported, “Biological studies in crop-destroying agents were suggested to the Chemical Warfare Service as early as March 1942, when it was reported that investigations of the agents of late blight of potatoes, rice fungus, wheat rusts, rubber leaf blight, and plant growth inhibitors might prove profitable” (PDF pg. 445).

U.S. research on plant BW was centered at the Plant Research Branch, and later the Crop Research Division at Camp Detrick, Maryland. Bioweapons work, which had operated out of the Army’s Edgewood Arsenal, was shifted to the new Detrick facility in 1943. OSS documents, however, state that the chemical materials described further on in this article, associated with the work of its Special Assistants Division, continued to be stored at Edgewood.

Years after these events, a 1977 U.S. Army report, U.S. Army Activity in the U.S. Biological Warfare Programs (PDF), stated, “By the end of World War 2, a wide variety of disease agents effective against man, animals, and plants had been studied and limited field testing conducted” (pg. 1-4).

The Army report explained: “At its peak, the Special Projects Division of the Army CWS, which was the main element for carrying out the program had 3,900 personnel, of which 2,800 were Army, nearly 1,000 Navy, and the remaining 100 civilian. The work was carried out at four installations: Camp Detrick was the parent research and pilot plant center; field testing facilities were set up in the summer of 1943 in [Horn Island] Mississippi, another field testing area was established in Utah in 1944 [at Dugway Proving Ground]; and a production plant was constructed in [Vigo] Indiana in 1944.”

The report stressed, “All work was conducted under the strictest secrecy” (pg. 1-3).

The Army report, released in the 1970s during a period when there were a spate of government scandals about covert operations, informed its readers, “During World War 2, the policy of BW use implicitly paralleled the policy for Chemical Warfare (CW); that is, retaliation only” (pg. 1-3).

But Summers’ declassified OSS report shows that later public admissions concerning the U.S. biowar program did not tell the entire story. The U.S. government has never come completely clean in regards to its history surrounding use of biological weapons.

In his top secret July 1945 “Summary of Activities of Special Assistants Division” report, Captain Summers explained that his unit was kept informed regarding the latest developments in both enemy and allied biological warfare work through OSS’s Secret Intelligence, Research and Development, and Counterintelligence (X-2) branches, as well as via the military’s Criminal Investigative Division, the CWS, and briefings from the Assistant to the Advisor to the Secretary of War.

It’s not clear who the “Advisor” was, but my best guess is that it was Colonel R. Ammi Cutter, who was Assistant Executive Officer to John J. McCloy in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War. McCloy had initially joined the War Department as a special advisor to Secretary of War Stimson. According to an official biography by the State of Massachusetts, Cutter’s duties at the War Department “included planning for the military governments in Germany and Japan, researching war crimes prosecutions, and looking at issues regarding treatment of American prisoners of war in enemy hands.”

According to Summers, OSS officials did not perform BW experiments themselves (see pg. 13 of OSS reports PDF), but they had visited “areas where BW research and development was being performed and maintained contact with proper personnel” (pg. 5 of OSS reports PDF).

Secret orders

A separate top secret OSS review, titled “Final Summary Report on BW,” described the covert nature of the authorities surrounding the BW program. The report was written by Captain Summers in September 1945, hence after the end of hostilities with Japan. It included two appendices: one on “Enemy Activity” as it pertained to biological weapons, and another on “Possible BW Devices” for use on either “personnel” or “vegetation.”

“There is no letter of authorization in the Special Assistants Division files” regarding OSS’s participation in the biological warfare program, Summers wrote. He explained further, with reference to himself in the third person, “but it is understood from Major A. Gregg Noble, former Chief of Special Assistants Division, and from Captain Donald B. Summers, present Chief of Special Assistants Division that such authorization was given orally by Mr. Stanley P. Lovell, former Chief of Research and Development Branch and also by Lt. Colonel John M. Jeffries, present Chief of Research and Development Branch” (italics added for emphasis, pg. 12 of OSS reports PDF).

This is not the only reference in OSS materials to sharing information secretly via verbal communications. In his book on Lovell and OSS, cited earlier, John Lisle described a January 22, 1945 memo from Major Noble, “Status Summary of Projects Special Assistance Division,” which stated, “This information has been passed on only verbally by Mr. Lovell and Dr. Chadwell allegedly from Dr. Van Bush” (Lisle, pg. 281).

I don’t know what program Noble was referencing. At the time, it’s likely Noble was still SAD’s chief. Harris Chadwell was the director of R&D’s Division 19, which focused on secret spy and special operations weaponry. “Van Bush” was really Dr. Vannevar Bush, head of the government’s Office of Scientific Research and Development, which oversaw all government research and development during the war. So this discussion was occurring at very high organizational levels.

Summer’s Final Summary Report also described the purpose of the BW program: “It was desired that OSS be aware of all possible developments both offensive and defensive made in the U.S. and in foreign countries and that Research and Development of OSS be in a position to recommend and made [sic] suitable BW devices should the opportunity present itself” (OSS Documents PDF, pg. 12).

The report concluded, “OSS could wage BW both against plants and animals in a relatively short time” (Ibid.).

Summers also indicated that OSS, including its Research and Development Branch, was set to shut down at the end of 1945, and he presumed that the Chemical Warfare Service would continue to run the BW operation during peacetime. Earlier, in his July monthly report on SAD activities, Summers had strenuously argued that the R&D branch work not be discontinued, and that the department should be preserved somehow after OSS was shuttered. Since, as we’ve seen, some important information was only passed down verbally, the importance of maintaining organizational or personnel continuity can be readily understood.

The OSS use of oral authorizations regarding BW in World War 2 illuminates the issue of how secret orders regarding biological warfare were communicated more generally. This includes possibly during the Korean War, when the U.S. was charged with a secret campaign of germ warfare against China and North Korea. Use of special verbal authorizations for secret operations may also extend to other nations, such as both German and Japanese research and operations surrounding their own chemical and biological weapons programs.

We have evidence of the oral provision of orders relating to biological warfare during the Korean War from a declassified Summary History of the U.S. Chemical Corps, dated October 30, 1951, which revealed that under the pressures of intense warfare and U.S./UN military setbacks on the Korean peninsula, the U.S. Army Chemical Corps leaders gave a “terrific push” to the development and creation of new biological and chemical agents. The relevant secret orders were delivered orally (for the quote re “terrific push,” see pg. 3).

As described in this previously top secret internal history, the Chief Chemical Officer of the Chemical Corps at the time, Major General Anthony C. McAuliffe, “issued verbal instructions that, regardless of previous plans,” both chemical weapons and “a BW interim weapon” “were to be rushed to completion” (pg. 11 — italics added for emphasis). Per the footnote for this material, it seems McAuliffe’s verbal orders on developing an interim BW weapon were given as early as August 1950.

Only months after the Chemical Corps Summary History was released, captured U.S. airmen told their Chinese captors that at least some of the military directives on use of biological weapons were “verbally directed,” according to Colonel Frank Schwable, who was Chief of Staff for the First Marine Air Wing and the highest ranking Marine Corps officer captured during the Korean War. Schwable explained how sensitive BW information was withheld from key units, while orders for its use were handed down “personally and verbally.”

For security reasons, no information on the types of bacteria being used was given to the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing….

During the latter part of May, 1952, the new Commanding General of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, General [Clayton C.] Jerome, was called to 5th Air Force Headquarters and given a directive for expanding bacteriological operations. The directive was given personally and verbally by the new Commanding General of the 5th Air Force, General Barcus.

Secret verbal orders are not confined to covert use of biological weapons, nor to World War II and the Korean War. For instance, turning to the era of the Vietnam War, Congressional investigations documented that the orders and instructions for the U.S. Air Force to secretly bomb Cambodia were delivered orally.

Anti-crop agents: LN8, “feather bombs” and a “balloon gondola”

A 2015 review by Lawrence Roberge on the use of biological weapons against agriculture stated, “Biological weapons research in the United States during World War 2 included the development of anti-crop chemicals which were defoliants: 2,4-dicholorophenoxy acetic acid (2,4,-D) and 2,4,5-tricholorophenoxy acetic acid (2,4,5-T) [8,11]. Further research in anti-crop agents was directed at the fungal pathogens: P. infestans (Potato blight), Sclerotium rolfsii sacc (Sclerotium Rot of sugar beets), Piricularia oryzae Br. and Cav. (Rice blast), and Helminthosporium oryzae van Brede de Haan (Brown Spot of rice).”

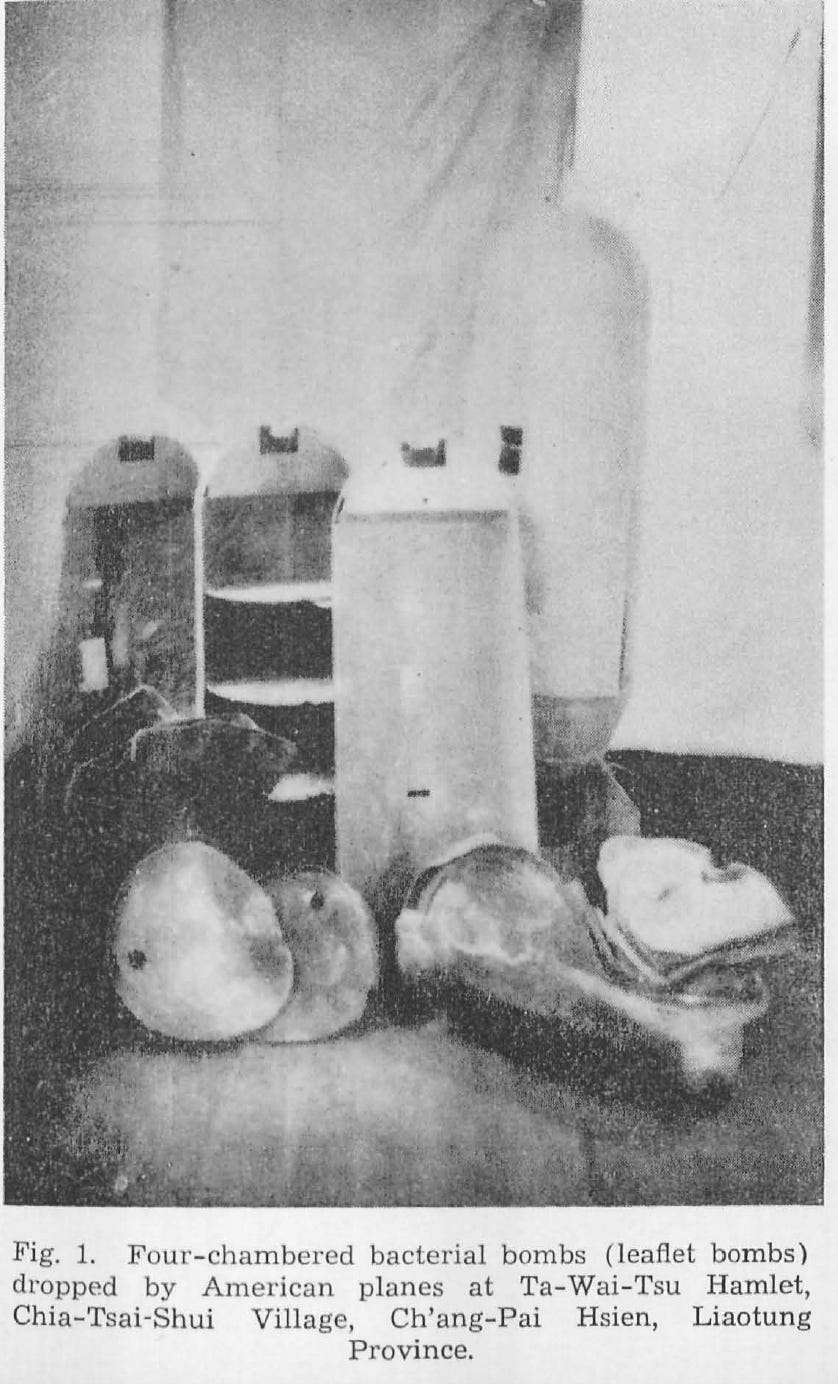

According to Roberge, by the 1950s the U.S. was mass-producing plant pathogens, along with other forms of biological weaponry. By this time, the U.S. was developing a “feather bomb” and other anti-crop dispersal devices, including “large volume spray tanks to disperse dry anti-crop BW agents which could with one aircraft disperse a plant disease epidemic over an area in excess of 1,000 square kilometers.”

There were other dispersal devices as well, including “a balloon gondola which could under the proper weather conditions carry five containers of feather/fungal spores deep into enemy territory.”

These are very similar to devices used by Japan’s biological warfare division, Unit 731, and also to devices allegedly used by the United States against North Korea and China during the Korean War. In two earlier articles (see here and here), I outlined Japan’s own use of high-altitude balloons to potentially disperse biological agents (and apparently did so in some limited fashion), as well as the later U.S. “Flying Cloud” balloon project, modeled in part after Japan’s balloon assault, and designed to deliver the “E-77” biological feather bomb developed by Camp Detrick’s Special Operations Division.

OSS plans for anti-crop BW included both actual biological agents and chemical defoliants. According to SAD’s Final Summary Report, referenced earlier, the substances codenamed “IR” and “E” were said to be “available in fairly large quantities” (pg. 16). According to an appendix on bioagent codenames in Cochrane’s 1947 history of the Chemical Corps, quoted earlier, “IR” and “E” referred to the pathogens Rice Blast and Brown Spot of Rice, respectively.

It’s clear that by summer of 1945, the U.S. military had stockpiled use of biological agents and defoliants for use against Japan’s rice crop. (The Cochrane appendix on codenames has been transcribed and the reader can find it at the end of this essay.)

Rice Blast is a fungus that destroys the leaves on rice, and has been responsible for famines in rice growing areas. Brown Spot is a disease that forms lesions on rice plants. Controversially, the Americans tested its use as a biological weapon in Okinawa in the 1960s.

Despite the existence of biological agents to use on enemy crops, OSS felt that that when it came to anti-crop agents, one particular herbicide was deemed “most satisfactory.”

Called LN8, the OSS rapporteur described it as a “white crystalline solid,” “very stable” and “1% soluble in water.” When applied, it could produce a “withering and yellowing” of leaves in one to three days. (See page 17 in my collection of relevant OSS files.)

“In a week to ten days the vegetation is completely stripped of its leaves,” the report stated, “the stalks fall over and the plant dies or fails to bear fruit.” Various methods of dispersal were discussed, including modification of a DDT aerosol bomb with a delayed fuse release (“a time pencil” in OSS jargon).

Dow Chemical’s Special Projects Division manufactured LN8, according to a 2016 report by Joseph Trevithick at The National Interest.

“In April 1945, B-25 bombers with 550-gallon tanks in their bomb bays sped across test fields at Terre Haute, Indiana and Beaumont, Texas…. The Pentagon clearly envisioned a similar series of crop busting strikes,” Trevithick wrote.

The OSS BW summary report also discussed “possible BW devices for use against personnel.” One very lethal substance, botulinum toxin, called “X” in the report, “could be utilized in pills, pellets or powders that could be given in drink or spread on food.” It could also be put in “food stores or in water supplies.” Placed into “Carbowax,” the lethal substance could be put onto a “bullet, dart, or arrow” (pg. 16, OSS documents). Death would come via the shot itself or from a following infection. There was no antidote.

“The material maybe [sic] obtained from the Special Projects Division, CWS,” the report noted.

U.S. Use of Japan’s Unit 731 BW Experiments

In the 1952 report of the International Scientific Commission, headed by British scientist Joseph Needham, observers accused the United States of the use of plant biological warfare. In particular, packets of plant material dropped by U.S. planes were tested and found to contain various pathogens, including purple spot fungus, or Cercospora sojini Hara, which infects soybean crops; a species of Thecaphom, found on maize kernals, of a type never found in China or Korea before; and anthracnose (Glomerella), which infects a number of different plants, among other pathogens.

Unknown to Needham and others investigating germ warfare charges during the Korean War, after World War 2, General MacArthur, in conjunction with U.S. agencies, had helped negotiate a blanket amnesty with the leading members of Japan’s World War 2 biological warfare Unit 731, as part of a trade for the data gathered by the Japanese on illegal, fatal BW human experiments on thousands of prisoners. Ishii and his co-workers had also worked on biological warfare agents aimed against plants.

Needham and others had suspected that Unit 731’s leader, Shiro Ishii, and his associates, were involved in the biological warfare campaign they believed was used against both China and North Korea during the Korean War.

According to historian Sheldon Harris, during World War 2, the main Unit 731 facility at Pingfan, Manchuria, “was equipped with several greenhouses that were used for plant BW experiments” (pg. 43). But the main anti-crop operations were at Japan’s Unit 100 center. The facility consisted of 20 square kilometers of experimental farms in the suburbs of Changchun, surrounded by 3-foot high electrical fences, where crops “would be subjected to experiments with various types of plant-killing bacteria” and different herbicides and pesticides (pg. 116).

By the end of World War 2, the U.S. was already aware of some of this research, although they did not know all the particulars at that point. According to a top secret annex to the Final Summary Report on BW discussed above, the Japanese were known to have developed use of pathogens (such as tylenchus tritici) to use against wheat, barley, rye and potatoes.

In an incredible admission, according to the OSS report, the U.S. was utilizing Japanese methods of germ warfare even before the end of the war, and prior to the amnesty deal worked out with Ishii and his associates.

Japan has “perhaps the best informed scientists in BW investigations of any nation in the world,” the OSS report stated. “The Japanese investigations were extremely extensive and intensive so that some of the U.S. research utilized Japanese methods and techniques…. There is no evidence of mass production of these agents, although experimental secluded installations were known. Of course, the Japanese had no scruples hindering them, as U.S. has, from the use of these devices but no large scale operations were expected…. They did have an experimental bacterial bomb which has never been proved used” (italics added for emphasis; see pp. 15-16 of OSS documents).

It is deeply hypocritical that the OSS would criticize a lack of “scruples” among Japanese scientists, when U.S. scientists and officials were contemplating, if not organizing themselves, the use of biological weapons against humans, animals, and crops, not to mention having actuated the use of atomic weapons against Japan’s population, killing many tens of thousands of people.

The first inkling of how massive the Japanese BW undertaking actually was came in the form of a report from the U.S. War Department’s Military Intelligence Service. Dated April 6, 1945, the report described how POWs had verified a Bacteriological Experimental Center commanded by Ishii in Harbin, China, according to the account given in Ed Regis’s book, The Biology of Doom: America’s Secret Germ Warfare Project (p. 85).

“Nature of the types of experiments being carried on here is extremely secret and their findings were never published for general assimilation,” the report stated.

It is also possible that the Americans knew of another secret germ war facility in Niigata Prefecture, Japan, and as a result had placed that city on a list of possible targets for nuclear bombing. According to an investigation by the Japanese newspaper, Niigata Nippon, published August 6, 1987, the Niigata facility was a joint project of Unit 731 and Japan’s secret military research office at Noborito, involved in the BW aspect of Japan’s secret “Fu-Go” balloon barrage project against the United States. (Thank you to staff at the Imperial Japanese Army Noborito Laboratory Museum at Meiji University in Japan for bringing this article to my attention.)

I will be reporting more on the Niigata story in a future article. But it’s intriguing to note here that in Summers’ September 1945 report on “Enemy Activities” relating to biological weapons, he noted that some Japanese "experimental secluded installations [for production of biological agents] were known" (pg. 15 of OSS BW Reports PDF).

In any case, it turned out that the U.S. underestimated the extent of Japan’s BW program at the end of World War 2. Over the next few years, various U.S. investigators would interrogate and debrief Japanese scientists, while receiving permission from Washington D.C. to provide amnesty to the Unit 731 war criminals in order to further the BW aims of U.S. researchers. Government spokespeople over the years have indicated that the purpose for the amnesty was to keep valuable BW data out of the hands of the Soviet Union.

While there was an initial intent to end the U.S. biological warfare program at the end of World War 2, those in charge of the program successfully lobbied to keep the research alive. Over the next few years, the BW program at Camp Detrick (which was renamed Ft. Detrick in 1956) and associated centers would receive a massive influx of funding, and BW testing began anew. At the same time, the U.S. resumed its special wartime collaboration with the germ war programs of Canada and the United Kingdom, which continued to conduct a secret “tripartite” collaboration on BW during the Cold War.

The most controversial trial of an operational BW program may have been that undertaken by the United States during the second two years of the Korean War. The U.S. strenuously denied North Korean, Russian, and Chinese charges of use of BW, either against humans or plants, and called for an “independent” investigation by the International Committee of the Red Cross or the UN’s World Health Organization.

But behind the scenes U.S. government authorities working under the auspices of the Psychological Strategy Board (PSB), staffed by top intelligence, military and State Department figures, were adamant the U.S. would never allow an independent investigation of use of biological weapons in Korea.

According to a memorandum of a PSB meeting in July 1953, the U.S. was opposed to an “actual investigation” that could expose Korean War military operations, “which, if revealed, could do us psychological as well as military damage.”

The memorandum specifically stated as an example of what could be revealed “8th Army preparations or operations (e.g. chemical warfare).” Given the history of how biological and chemical warfare techniques were admixed in U.S. usage, as we have seen above, it is not infeasible that the document was coyly referring to U.S. use of biological weapons.

In 2010, the CIA declassified a number of communications intelligence reports from the Korean War. According to my research, at least two dozen of these formerly secret documents quoted decrypted secret communications from Chinese and North Korean military units that indicated they were under attack by U.S. germ war weapons. For a fuller discussion, see my article published in the Journal of American Socialist Studies, Issue 3 (2024-2025), “‘The enemy dropped bacteria’: CIA Korean War Daily Reports Affirm Allegations of U.S. Germ Warfare.”

References

See U.S. National Archives, “Final Summary Report on BW [Biological Warfare], from the Special Assistants Division, Research and Development Branch,” September 27, 1945, 7 pp., Records of the Office of Strategic Services (Record Group 226) 1940–1947, Entry 211, Box 20 of 45. Location: 250/64/32/1. CIA Accession: 85–0215R. Folder “G/6, Med Res. Lab #3”

Appendix — Code Names for Biological Agents

In alphabetic order (from Cochrane, 1947, pp. 518-519):

Agents injurious to rice — Code “II”

Anthrax — Code “N”

Botulism — Code “X”

Brown Spot of Rice — Code “E”

Brucellosis — Code “US”

Cholera — Code “HO”

Coccidioides, aka San Joaquin Valley fever — Code “OC”

Dysentery — Code “Y”

Foot and Mouth Disease — Code “OO”

Fowl Plague & Newcastle Disease — Code “CE”

Glanders — Code “LA”

Japanese Type B Encephalitis — Code “AN”

Late Blight of Potato — Code “LO”

Mass Culture of Spores — Code “AU”

Melioidosis, aka Whitmore’s Disease — Code “Hi”

Mussel Poisoning — Code “SS”

Neurotropic encephalitises — Code “NT”

Plague — Code “LE”

Plant Growth Regulating Substance — Code “LN” [There were a number of subtypes of these; for example, 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) was codenamed “LN8”]

Psittacosis, aka “Parrot Fever” — Code “Si”

Rice Blast — Code “IR”

Rickettsiae — Code “RI”

Rinderpest — Code “R” or “GIR 1”

Sclerotium Rot, aka Southern Blight — Code “C” or “Co”

Tularemia — Code “UL”

Typhus — Code “YE”

This article was adapted and updated from an earlier article, “Secret Report: US Military Approved Offensive Use of Biological Warfare on Enemy Agriculture in World War 2,” published at Medium.com on May 14, 2018.