Debunking the Debunkers, Part 2: Anatomy of a Plot

Beria's respondents on supposed false germ warfare charges couldn't keep their stories straight. Yet Cold War scholars & a generation of academics & journalists ignored obvious evidence of a frame-up

There are many false statements and claims in the documents used by Cold War scholars to invalidate the old, but explosive, Communist charges of U.S. use of biological weapons (BW) during the Korean War. It has been tedious work to document the lies and misrepresentations. I hope that it won’t be so tedious to read about them! What’s at stake here is nothing less than the truth about one of the biggest war crimes the U.S. ever conducted. Precision is a virtue here. All I can add is that if you haven’t already, do read the first part of this series, Debunking the Debunkers: Prelude to a Frame-up. It isn’t necessary to have read it to read or understand this article, but it will put the material below into greater context.

Validating the Incredible

When I left off in Part 1 of this series, I had just explained how twelve purported Soviet documents were published in 1998 by the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) at The Wilson Center. These documents claimed to chronicle the construction of false sites of bacteriological infection. The entire forgery was said to originate in a conspiracy among North Korean, Chinese, and Soviet officials.

The fabrication of fraudulent biological warfare (BW) sites was explained by researchers Kathryn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg to be part of a campaign to deceive international investigators. These investigators had traveled to Korea and China in part to examine the germ warfare charges against the U.S. made by the North Korean and Chinese governments.

Although in 2016 Milton Leitenberg released additional documents said to come from Russian archives, which included some Soviet documents from the Korean War period, nothing in this later release substantially added to the charges and claims made as a result of the 1998 documents. [1]

The 1998 Soviet archival documents were widely accepted by the academic community, which is surprising, as the evidence they present cannot withstand even casual textual analysis, much less the close examination of the content they should have received. Critical analyses of these documents are few and far between, though there have been a few important such works. [2] The primary, unanalyzed problem with these documents lies with the contradictory timeline they present for the central events under discussion.

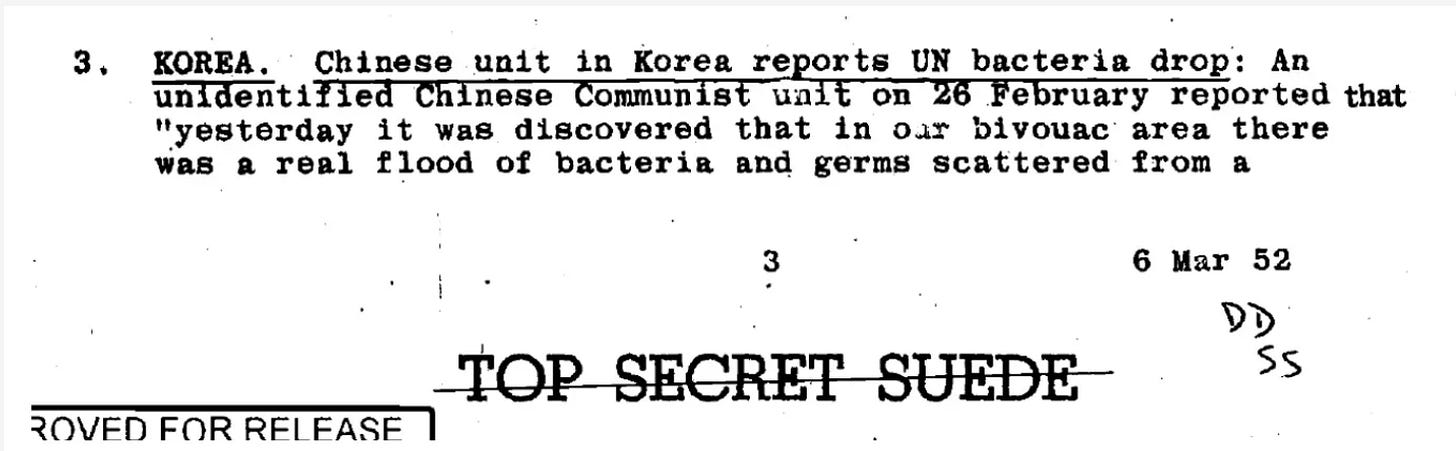

The CIA COMINT materials, discussed in Part One of this series, contain powerful disconfirming evidence bearing upon the validity of the Weathersby/Leitenberg documents’ historical account of events. Briefly, the COMINT records were top secret CIA communications intelligence reports from the Korean War, now declassified. Two dozen of the released records had extensive citations from decrypted radio intercepts from North Korean and Chinese military units discussing aspects of the bacteriological and insect attacks they were then experiencing. I will return to the issue of these documents further below.

For the purposes of this essay, I will not question the provenance of the documents presented by Leitenberg and Weathersby, even though the manner in which they were obtained was, to quote Weathersby, “unusual.” No actual photocopy of these documents exists, only typewritten copies, which were made from a hand written copy, were ever made.

These transcribed copies were then published by the right-wing Japanese newspaper, Sankei Shimbun, whose reporter Yasuo Saito, Weathersby said, had originally obtained the documents “from the Russian Presidential Archive (known formally as the Archive of the President, or APRF)” (Weathersby, 1998, p. 176).

In her 1998 essay, Kathryn Weathersby cannot even state with assurance where the documents originated. According to her, Saito “purportedly obtained” the documents from the Russian archive. Because the copies were “copied by hand and subsequently retyped… We therefore do not have such tell-tale signs of authenticity as seals, stamps or signatures that a photocopy can provide. Furthermore, since the documents have not been formally released, we do not have their archival citations. Nor do we know the selection criteria of the person who collected them.” (Ibid.)

The “regrettable” origin of the documents meant, as Weathersby herself said, that careful “textual analysis” of the material was essential. The bulk of this present article will allow readers to judge for themselves just how good a job she did.

Nearly twenty years later, Leitenberg (2016, see endnote [1]) found some external evidence that at least some of the documents came from Soviet archives. Nevertheless, as presented in total, and for the reasons I will detail below, these purported Soviet documents are in fact unreliable as historical evidence of deception regarding U.S. use of germ warfare, and cannot represent proof that the BW charges were, as Leitenberg called them, “a grand piece of political theater.” From my perspective, they are unreliable not because of their provenance, but because they are evidence of a plot by powerful Soviet official, Lavrenti Beria, to defame and remove his rivals during the intense period inside the Kremlin in the months after Stalin died.

U.S. government documents, in the form of the CIA’s COMINT files, which quoted a number of units of the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army reporting varying forms of BW attack, nullify the claim that there was no biological weapons attack. Yet, because the Soviet archival documents are at the heart of Weathersby and Leitenberg’s assertions regarding the falseness of China and North Korea’s claims of U.S. attack by bacteriological weapons, we must examine them in some depth. We must undertake the deep textual analysis Weathersby failed to do.

When Kathryn Weathersby introduced the twelve Soviet documents in her 1998 essay, “Deceiving the Deceivers: Moscow, Beijing, Pyongyang, and the Allegations of Bacteriological Weapons Use in Korea,” she said, “The specifics of persons, dates and events are consistent with evidence available from a wide array of other sources…. their contents are so complex and interwoven that it would have been extremely difficult to forge them. In short, the sources are credible” (pg. 176). [3]

Yet, as I shall show, she failed to accurately describe the documents. The dates are inconsistent. External sources of information do not corroborate the narrative of the documents. In short, the sources are not credible.

The key assertion behind the “hoax” hypothesis concerns a memorandum sent by two Soviet advisers to the North Korean regime to top Soviet official Semyon Ignatiev. This memo, identified as written by Glukhov and Smirnov (no first names), ultimately ended up in the hands of Stalin’s former secret police chief, and possible heir to Stalin himself, Lavrenti Beria. The memo supposedly described Soviet participation in creating with the North Koreans false evidence of biological warfare attacks by the Americans.

In 1952, Glukhov was an adviser to the Ministry of State Security in the Democratic Peoples’ Republic of Korea (DPRK), while Smirnov was adviser to the DPRK’s Ministry of Internal Affairs. Ignatiev, as Minister of State Security, held high office in the Soviet Union at the time, and was a member of the Communist Party Central Committee. He was considered a rival to Lavrenti Beria.

The context surrounding the allegation of creating false evidence of bioweapons attack is that investigators, mostly European based, from the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL), were due to arrive in North Korea in early March 1952. Earlier, in September 1951, the IADL had decided that the organization would send a delegation to China and North Korea to investigate the charges of war atrocities, including use of poison gas and germ warfare, coming out of the region at the time. (Readers may notice that in some documents the IADL is referred to as the International Association of Democratic Jurists.)

The Glukhov/Smirnov memo to Ignatiev regarding the deception surrounding charges of U.S. germ warfare has never been published. It may not even exist. It was first described in Document #5 of the Weathersby documents published by CWIHP. This document consisted of a 21 April 1953 memorandum from then-Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Lavrenti Beria, to Georgy M. Malenkov and the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In other words, Beria was writing to the top officials of the Soviet political apparatus. Malenkov had just recently succeeded Stalin as Premier of the Soviet Union after the latter’s death in early March 1953.

Beria charged that Ignatiev had wrongfully withheld the Glukhov/Smirnov memorandum, with its supposedly damning details about the creation of false evidence of biological attack, from Soviet authorities. Glukov and Smirnov, acting here as whistleblowers, allegedly accused the Soviet ambassador to the DPRK, Lt. Gen. V.N. Razuvaev, of acting in concert with North Korean authorities to simulate “two false regions of infection... for the purpose of accusing the Americans of using bacteriological weapons in Korea and China.” (Weathersby, 1998, p. 182)

Even more, in order to manufacture false evidence of bacterial infection, Beria described how “[t]wo Koreans who had been sentenced to death and were being held in a hut were infected. One of them was later poisoned.” The bacteria from their corpses, allegedly cholera, was then used to supposedly trick investigators. (Ibid.)

Beria claimed that roughly a year after the whistleblower memo purportedly was given to Ignatiev, he (Beria) had found it “in the archive of the MGB USSR” after, he vaguely recalled, “receiving the matter at the beginning of April 1953.” (Ibid.) The MGB was the “Ministry of State Security” (Министерство государственной безопасности), the department then headed by Ignatiev.

Beria evidently then approached Glukhov and Razuvaev, as well as a Lt. Selivanov, a student in the Kirov Army Medical Academy who had been an adviser to the Military-Medical Department of the KPA, and had them all write letters in mid-April 1953 describing their part in the deception. Why Beria needed testimony about the plot to falsify BW attack from Glukhov and Razuvaev, when he presumably had the original Glukhov/Smirnov report at hand, is never explained.

According to the Selivanov document, Smirnov had apparently been an adviser for the DPRK’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Glukhov is identified by Weathersby as the Deputy Chief of the Department of Counterespionage of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Urals Military District. Weathersby wrote that in early 1952 Glukhov had been the “former adviser to the Ministry of Public Security of the DPRK.”

Glukhov and Joseph Needham of the ISC

Glukhov’s statement to Beria, which constitutes Document #2 in Weathersby’s essay (pg. 180-181), makes a number of astonishing claims itself. According to Glukhov, the North Koreans first “received information from Beijing that the Americans were using bacteriological weapons,” and insisted on publicly condemning this before the Chinese government did.

Glukhov claimed the North Koreans stated, “the Americans had supposedly repeatedly exposed several areas of their country to plague and cholera. To prove these facts, the North Koreans, with the assistance of our advisers, created false areas of exposure.” I suppose Glukhov meant the facts were alleged. Or did he? Glukhov never stated that the attacks never happened.

Glukhov continued: “In June-July 1952 a delegation of specialists in bacteriology from the World Peace Council arrived in North Korea. [This would have been the International Scientific Commission (ISC) — JK] Two false areas of exposure were prepared. In connection with this, the Koreans insisted on obtaining cholera bacteria from corpses which they would get from China.” (Why bother, by the way, to get cholera bacteria from China when there were cholera cases much closer at hand?)

The ISC had been formed by the World Peace Council after an appeal from China’s Academia Sinica. The WPC turned to famed British scientist Joseph Needham for assistance in forming a respectable scientific committee to visit China and North Korea to assess the BW charges. The ISC did in fact hold such an investigation, and visited North Korea in late July and early August 1952. They issued a detailed report of their investigation in September 1952, which was quite controversial. I wrote up the whole episode, plus downloadable ISC report, which can be accessed here.

I want to point out that Glukhov had said that the “two false areas of exposure” were constructed in June or July 1952. But Beria, in his memo to Malenkov (Document #5 mentioned above), said the “two false regions of infection” were mentioned in Glukhov’s own report (co-authored with Smirnov), and forwarded to Ignatiev in the first week of March 1952. So when were these “two false regions” actually assembled? If readers are confused at this point, they should be! The case presented by Beria, as well as the statements he gathered in its support, are full of tangled timelines and false, often outrageous claims.

As an example of a bizarre and outrageous claim, Glukhov closed his statement by relating how the North Koreans, in order to make “an unworkable situation” for the ISC investigators, set off explosions near the investigators’ residence, and organized false air raid sirens to scare them when they visited Pyongyang. In fact, the U.S. was carpet-bombing Pyongyang and much of the rest of North Korea at this time, and there was no need to conjure up any explosions.

In a diary of his dangerous trip with the ISC to North Korea in late July and early August 1952, the de facto head of the ISC, British scientist Joseph Needham, described how they travelled in camouflage, and saw “devastation” and burning houses. Having reached Pyongyang, they were housed in a tunnel 30 feet underground. Needham recalled air raids as they were dressing. The area was bombed around midnight of 31 July or 1 August, and their underground residence had “four near misses.” An “a/r [air raid] warden” outside the tunnel where ISC personnel were residing was killed in the attack.

Glukhov’s claims of “fake” North Korean explosions likely originated in the ambitious, fevered mind of Lavrenti Beria.

The Case of Lt. Selivanov

Each of the submissions provided to Beria have serious problems with their narratives. But the issues aren’t wholly internal to the documents. There are also problems with how these documents are described after the fact years later by U.S. authors and institutions.

The third of the twelve documents put forward by Kathryn Weathersby was a so-called “Explanatory Note” written by Lt. Selivanov to L.P. Beria on April 14, 1953. As noted above, while in Korea, Selivanov had been an adviser to the Military-Medical Department of the Korean People’s Army. He likely was based in Pyongyang.

In his note to Beria, Selivanov stated that in March 1952 he told Sergei Shtemenko, Chief of the General Staff of the Soviet Armed Forces, following an “inquiry from the General Staff of the SA [Soviet Army], that there are not and have not been instances of plague or cholera in the PRC, there are no examples of bacteriological weapons, [and] if any are discovered they will be immediately sent to Moscow.”

It’s not clear if Selivanov, who was a minor official at best, and was stationed in North Korea, was referring to Korea when he said there were “no examples” of BW. In any case, he was not well-placed to report on potential germ warfare attacks in the PRC, i.e., in China. In fact, it makes no sense that the Soviets, who had regular communications with their allies in the Communist Party of China, would turn to a junior officer in North Korea for information on pathogens appearing in China! The entire note, like the others Beria gathered, reads like a put-up job, and often makes no logical sense.

In his first paragraph, Selivanov stated that North Korea’s charges in February 1952 that the U.S. was using biological weapons were made “in order to compromise the Americans in this war.” Even more, regarding the officials of the DPRK, he said, “to all outward appearances, they seriously believed the information about [the BW attacks] that they received from the Chinese. Kim Il Sung even feared that bacteriological weapons would be used regularly.” Upon what evidence did Kim base such a fear? On counterfeit evidence from his own people? The mere idea is absurd.

The alleged North Korean rationale for promoting a false story about BW attacks, i.e., that it would “compromise the Americans,” reappeared in Weathersby’s Document #11, a June 1, 1953 telegram from the USSR Charge d’Affaires in the DPRK, S.P. Suzdalev, to V.M. Molotov and copied to other high Soviet officials. The message described a supposed meeting between Suzdalev and the Secretary of the Central Committee of the Korean Workers' Party, Pak Jang-ok [Pak Chang Ok]. (See Weatherby, 1998, p. 184.)

Told by Suzdalev that the Soviet Union wished to stop the propaganda about U.S. germ warfare, Pak responded with “great surprise.” Pak told Suzdalev, “We were convinced that everything was known in Moscow. We thought that setting off this campaign would give great assistance to the cause of the struggle against American imperialism.” Suzdalev didn’t expand on what “everything was known” entailed.

The theme that the Communists’ BW propaganda had been primarily used for a campaign to impugn the United States also appeared in contemporary internal CIA analyses, which stated that Communist propaganda on U.S. BW use was intended as part of a “Hate America” campaign. Funny that the same rationale appears in the Beria frame-up documents! The simpler interpretation is that North Korea and China were very upset by the use of such weapons and tried to alert the world about what was going on.

It’s worth pointing out there is nothing in this telegram to say that anything had been falsified, although, bizarrely, Suzadalev reports Pak was willing to say that “bombs and containers were thrown from Chinese planes, and [that] there were no infections.” This material is nonsensical. No one else has ever made such a claim about Chinese planes dropping any materials that could be considered possible biological munitions. In the end, Pak said he would report to Korean leader, Kim Il Sung, on the Soviet recommendation to curtail BW propaganda. As reported further below, the North Koreans, however, never stopped accusing the U.S. of use of germ warfare, despite Suzadalev’s request they do so.

Today, we know that the North Korean government did not rely solely on Chinese reports of bioweapons attack, nor did they have to manufacture any evidence. For one thing, the COMINT documents show that the KPA investigated allegations of BW attack, and numerous instances of such use were reported among military units.

A March 1952 report from the Commission of the Medical Headquarters of the Korean People’s Army on the Use of Bacteriological Weapons, a portion of which is reproduced below, shows where and when KPA medical staff investigated fifteen alleged drops of “infected insects” in February and early March 1952. If you’re keeping track of the timeline, six of the incidents in the chart are dated prior to the alleged discussions between North Korean officials and their Soviet advisers about falsifying BW sites of infection.

There’s more that can be gleaned from a close look at the Selivanov material. While first stating that North Korean officials believed they were under BW attack, later in his relatively brief note, Selivanov nevertheless stated that (unnamed) North Korean officials turned to Soviet advisers to help them in “creating sites of infection”:

Before the arrival in Korea of the delegation of [IADL] jurists, the North Korean representatives were seriously worried that they had not succeeded in creating sites of infection and constantly asked the advisers at MID [Ministry of Foreign Affairs], the Ministry of Health and the Military-Medical Administration of the KPA—advisers Smirnov, Malov and myself—what to do in such a situation.

You would think that Selivanov would then expand upon what he or other advisers did in response to the request from DPRK officials. But instead, the note then abruptly ends. Selivanov simply states after the quoted paragraph above, “At the end of April 1952, I left the DPRK.”

One must have sympathy for a junior official — a “student,” no less — asked by the powerful and scary former chief of the secret police to provide evidence of a supposed cover-up of fake BW evidence. It would seem Selivanov did the bare minimum to survive this situation.

But how does one account for Cold War ideologues at The Wilson Center, decades after the fact, dishonestly referencing his statement? A summary of Selivanov’s “explanatory note” to Beria on a webpage for Wilson Center’s Digital Archive, states, “Selivanov… describes how he falsified an outbreak and blamed it on American bacteriological weapons.”

In fact, as anyone reading the Sevivanov’s document can see, he did no such thing! In their summary, The Wilson Center apparently followed Weathersby’s 1998 description of Selivanov’s statement, which appears as Document #3 in her presentation (pg. 181) of the alleged Soviet archival documents.

“The statements of these three describe in detail [Documents Nos. 2, 3, 4] remarkable measures taken by the North Koreans and Chinese, with the assistance of Soviet advisers, to create false evidence to corroborate their charges against the United States,” Weathersby wrote (bold in original).

In summary, Kathyrn Weathersby in effect said Selivanov’s document described “in detail” extraordinary efforts “to create false evidence.” That’s not true. What Selivanov did (allegedly) say was that he was approached by DPRK officials about a problem with evidence; that he knew nothing about biological warfare or pathogens in China (or perhaps in North Korea either); and that in 1951 he “helped Korean doctors compose a statement about the spread by the Americans of smallpox among the population of North Korea.” He never said anything was falsified, much less that he was involved in such activity.

If the Weathersby/Leitenberg documents and analyses read more and more like a creaky frame-up, that’s because they originated in L.P. Beria’s own ramshackle conspiracy narrative. The subsequent use of this material by U.S. Cold War scholars was meant to provide documentary evidence of a Soviet-North Korean-Chinese conspiracy to falsify BW evidence. As shown below, there’s much more to demonstrate how, on just a prima facie examination, the alleged Soviet archival documentation proves only its own untruth.

Shifting Dates

A crucial point of my argument centers on Beria’s 23 April 1953 report to Malenkov (Weathersby Document #5). It’s in this document that Beria claims Ignatiev had received the Glukhov/Smirnov report in early March 1952, prior to the entry into North Korea of investigators from the International Association of Democratic Lawyers. Recall that the IADL had come to North Korea to investigate the BW charges, and other atrocities. The IADL representatives travelled around North Korea from 3 March to 19 March, after which they traveled to China for a brief period to look into BW reports from that country.

But in a surprising change of the timeline, referenced elsewhere in the Soviet documents without any comment by either Kathryn Weathersby or Milton Leitenberg, other supposed Soviet archival documents from the 1998 CWHIP release changed the date that Ignatiev received the Glukhov/Smirnov report from March to April 1952, a month later than Beria originally reported. We will return to the documents alleging a date for the Glukhov/Smirnov memo in April a bit later in this essay.

If we look at the timeline of the BW events — and the reader may have to pay careful attention here — we can see the problem with maintaining an early March date for the report. For one thing, the IADL identified the first documented BW insect vector attack as 28 January 1952 (the attack on Kanvon Province listed as #1 in the KPA chart reproduced earlier). On 22 February 1952, DPRK Foreign Minister Bak Hun-Yung went public with charges of alleged U.S. BW attacks. His speech was reported on the front page of China's People's Daily, which included pictures of bacteria slides and objects dropped in the attacks. Both these events predated the supposed fake BW conspiracy.

Bak’s speech is difficult to obtain from Western sources. It can be read in full in the latter half of this article.

According to Weathersby’s Document #4 — a 18 April 1953 “explanatory note” from Razuvaev to Beria — Razuvaev claimed to have been approached by North Korean leaders Kim Il Sung and Bak Hun-Yung about falsifying BW evidence after a meeting with them on 27 February 1952, but before the arrival of the IADL investigators five days later on 3 March. Razuvaev said the North Koreans were concerned that “an international delegation was coming.” Left unsaid was that the delegation’s purpose was already known: the investigators were coming to look at the evidence for germ warfare and other atrocities. Since there supposedly was no evidence of germ warfare, Kim and Bak allegedly asked Razuvaev what they should do in this situation.

Razuvaev’s note described how in a matter of a few days a plan was worked out involving the DPRK Ministry of Health. Here is what Razuvaev (allegedly) wrote to L.P. Beria, who in part one of this series I had posited was the true author of this defamatory tale. The date of Razuvaev’s statement is 18 April 1953.

False plague regions were created, burials of bodies of those who died and their disclosure were organized, measures were taken to receive the plague and cholera bacillus. The adviser of MVD [Ministry of Internal Affairs] DPRK proposed to infect with the cholera and plague bacilli persons sentenced to execution, in order to prepare the corresponding [pharmaceutical] preparations after their death. Before the arrival of the delegation of jurists, materials were sent to Beijing for exhibit. Before the arrival of the second delegation [[presumably the ISC - JK]], the minister of health was sent to Beijing for the bacillus. However, they didn’t give him anything there, but they gave [it to him] later in Mukden.

Moreover, a pure culture of cholera bacillus was received in Pyongyang from bodies of families who died from using poor quality meat. (Weathersby, 1998, p. 181, bracketed material in the original, double bracketed material added by this author)

The “adviser” to DPRK’s MVD was Smirnov, co-author of the report with Glukhov. No statement to Beria from Smirnov is known to exist, even though he is singled out as the originator of the plan to create false infections.

This hasty conspiracy makes little sense, and it doesn’t fit known facts. Could a conspiracy really be put forth between 27 February and 3 March 1952, robust enough to include the more than one hundred eyewitnesses interviewed by the skilled attorneys and judges of the IADL? Could all the documentary apparatus the IADL would examine — laboratory reports, autopsies, etc. — be falsified and assembled in such a short time? Could prisoners really be infected with cholera or plague, and then executed in time to produce bacteriological evidence post-mortem of the diseases, all within three to five days? Could, in wartime, officials travel from North Korea to China and back, carrying dangerous pathogens on the return trip, all within a handful of days?

Let’s not forget that this brief five-day time period between the hatching of the plot on 27 February and the appearance of the IADL investigators also had to include time to write the report on the false BW sites sent by Glukhov and Smirnov to Ignatiev before 3 March.

Here’s something even more suspicious. Since it seems likely the North Koreans had known the IADL had organized a delegation as far back as September 1951, when the intent to conduct such an investigation was first approved by IADL authorities, why would North Korea’s leaders wait until five days before the IADL was about to arrive to approach Soviet advisers for assistance?

There is also the fact that the IADL looked at many more than two sites of purported BW attack. Overall, according to their own report, published on 31 March 1952, the IADL examined sites in four different provinces and more than nine towns, including “Pyongyang, Nampo, Kaichen, Pek Dong, Anju, Anak, Sinchon, Sariwon, Wonsan etc.” [4] This is not something of which Milton Leitenberg was unaware, he just never makes any attempt to reconcile such reports with the Beria-originated documents.

The fact is there were documented reports of more than two sites of supposed germ war attack even before the IADL visit. Indeed, it’s worth reiterating that five days before Razuvaev claimed North Korea’s leadership asked Soviet advisers for help in counterfeiting sites of BW attack, DPRK’s Foreign Minister, Bak Hun-Yung, publicly accused the United States of using germ warfare, and “openly collaborating with the Japanese bacteriological war criminals” of Unit 731 in doing so. Bak cited twelve different instances of American BW bombing, further charging the U.S. with “systematically spreading large quantities of bacteria-carrying insects by aircraft in order to disseminate contagious diseases over our frontline positions and our rear.”

Fifty-eight years later, Bak’s accusations were corroborated by the COMINT documents referenced above and released by the CIA.

Returning to the issue of the Glukhov/Smirnov report, if it was sent to Igantiev in early March before the IADL had even arrived, as Razuvaev had suggested, that meant it had to have been sent on either 1 or 2 March. The entire set-up of the false deception sites had to be organized then in a matter of a few days, in addition to the fact the number of claimed falsified sites were less than the number of sites IADL investigators visited. Beria’s house of cards — later championed by Weathersby and Leitenberg — collapses upon even minimal examination.

Since the 3 March date is stated explicitly in the IADL report as the date IADL arrived in the country, it’s odd that Milton Leitenberg has maintained in multiple essays, going back to 1998, and as late as 2016, that the IADL entered North Korea on 5 March, not 3 March. (Yet he has the date correct in an old 1971 essay he wrote — see pgs. 241-242.) That’s either sloppiness, or possibly an attempt to fudge the dates in order to provide a few more days for the alleged Soviet-Chinese-North Korean conspiracy to be organized and carried out.

The alternative April 1952 date for the Glukhov/Smirnov report is first mentioned in a memorandum from the Chairman of the CPSU Central Committee Party Control Commission, Shkiriatov, to Malenkov on 17 May 1953 (Weathersby Document #10). “The note from Glukhov and Smirnov stayed with Ignatiev S.D. from 2 April until 3 November 1952,” Shkiriatov declared (Weathersby, 1998, p. 183).

This amounted to a notably different timeline for Ignatiev’s suppression of the Glukhov/Smirnov report than Beria had reported less than a month earlier — if you believe or trust the provenance and/or truthfulness of the documents themselves. [5] According to the Control Commission, Ignatiev received the report on 2 April 1952, and held it in his personal possession for seven months. The April date is repeated in the 2 June 1953 formal Control Commission decision condemning Ignatiev (Weathersby Document #12).

In the 22 years since these documents were made public, no one, neither Weathersby nor Leitenberg, nor their critics, nor any other commentator, has noted the discrepancy between the two dates surrounding the Glukhov/Smirnov report that supposedly exposed the germ warfare “hoax.” Yet the difference between the dates is crucial. The March date comes slightly before and the April date a few weeks after the three-week investigation by the IADL, which issued a “Report on U.S. Crimes in Korea” on 31 March 1952, and a separate report, “Report on the Use of Bacterial Weapons in Chinese Territory by the Armed Forces of the United States,” on 2 April 1952. [6]

If you are going to expose a criminal conspiracy to fool international investigators, it’s best you get your dates straight! Probably, for Beria, this was a tense, if not feverish, period, as he was jockeying and scheming to seize power in the first weeks after Stalin’s death, a period which overlaps with that of constructing the case about a BW “hoax.” There just wasn’t time to organize a conspiratorial tale that would hold water against the facts. By 26 June 1953, Beria was under arrest for treason and murder. This was barely three weeks after the Control Commission had ruled against Ignatiev.

In their Korea report, the IADL highlighted 15 different “typical cases” of insect drops, as identified by “observation posts of the Korean People's Army, the Chinese People's Volunteers and the Local Anti-aircraft Detachments,” while “different kinds of insects were found in 169 areas of North Korea.” The investigators concluded, “The examinations confirmed the local reports that different kinds of insects were being dispersed, and also established that the insects dropped were infected with plague, cholera and other epidemic diseases” (see endnote [4], pgs. 5-6).

Leitenberg and Weathersby offered no explanation for the differences in setting up only two false sites of infection, while the IADL examined at least 15 sites, not to mention the 169 other areas mentioned in their report.

Of even more concern, when one reads their essays carefully, it appears that both Weathersby and Leitenberg went out of their way not to mention the discrepancy in dates pertaining to when the Glukhov/Smirnov report was sent to Ignatiev. While the failure to note the different dates could be chalked up to sloppiness or mere oversight, the fact is both Weathersby and Leitenberg (and the latter on multiple occasions) made a point of summarizing and commenting upon the Soviet documents without ever mentioning the issue of the discrepant dates. They appeared to do this by eliding information (or again, they are just terrifically sloppy in their work), while subsequent scholarly readers and commentators have been negligent in analyzing the Weathsby-Leitenberg-CWIHP documents.

For example, in Kathryn Weathersby’s 1998 article introducing the Soviet documents, which she translated, she summarizes every single one of the twelve documents (marked in bold in her article) in the analytical portion of her essay, except Document #5, where Beria claimed the report exposing the falsification of germ warfare sites was given to Soviet security chief Ignatiev in early March 1952 (and then supposedly suppressed by the latter). Other Soviet documents she translated showed the date to be April 1952. She has had 27 years to correct her oversight or at least make mention of the discrepancy, but has not done so. I wrote to her some time ago to ask her to comment on this, but she never responded.

In his 1998 article, “New Russian Evidence on the Korean War Biological Warfare Allegations: Background and Analysis,” published jointly with Weathersby’s essay, in contradistinction to Weathersby, Leitenberg did describe Document #5, Beria’s report to G.M. Malenkov and the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. This report provided, as I’ve said, a March 1952 date for Gluckhov/Smirnov’s memo to Ignatiev. Beria didn't provide the exact date in March, but indicated the memo was written “before the arrival in Korea” of the IADL delegation (on 3 March).

But inexplicably, when it came time in the same essay for Leitenberg to describe Weathersby’s Documents #10 and #12 (the memo from the Chairman of the CPSU Central Committee Party Control Commission, and then the formal decision of the Control Commission itself, respectively), he failed to mention that these documents both described an April 1952 date for the Glukhov/Smirnov memo appearing in Ignatiev’s hands, a date Leitenberg would have known all too well came after the IADL had left Korea and had already published the results of their investigation. The entire narrative just doesn’t hold together.

The fact that Weathersby and Leitenberg’s errors are opposite in nature suggests that the two authors were not involved in any conspiracy to cover up the truth about what the documents actually represent. It is impossible to know, of course. But Leitenberg, who has written for years on this issue, has made many errors that lead one to question his efforts. A full analysis of each of these errors must await later publication, but let us consider a few of them.

The Weathersby/Leitenberg documents and the COMINT revelations

It must be pointed out that with the discovery of the CIA COMINT documents, the controversy surrounding the legitimacy of the Chinese and North Korean claims of U.S. use of biological weapons appears to have been settled. The COMINT reports join a number of other documentary sources, including hundreds of eyewitness testimonies gathered by both Communist and non-Communist investigators, the testimony of both Chinese and Western churchmen and missionaries, journalists, [7] and the efforts of two investigating committees of primarily West European origin, in validating the Chinese and North Korean claims. There was also, of course, much evidence publicized by Chinese officials at the time.

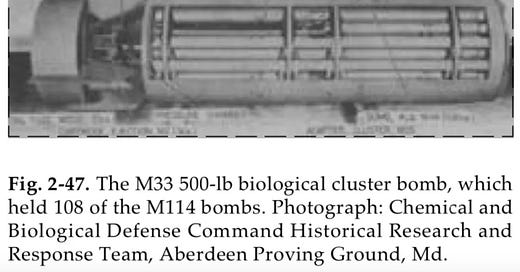

Statements made by UK and Canadian BW experts behind closed doors, briefings given to the FBI at the time, as well as a court affidavit from one of Ft. Detrick’s top scientists, also point strongly towards at the very least U.S. capacity to conduct germ warfare at the time of the Korean War, something that Milton Leitenberg has maintained did not exist (with the one possible exception of use of plant rust).

The COMINT reports disprove allegations made in the Weathersby/Leitenberg Soviet documents that North Korean and Soviet propaganda concerning germ warfare ended in early 1953. No one has put in print any objection to the COMINT evidence as dispositive regarding the germ warfare charges. Not one historian I’ve contacted has said to me that this evidence is problematic or wrong, or would go on the record doing so.

But informally I’ve been told the documents may represent an attempt to propagandize the Chinese and North Korean armies from within about the “fake” BW attacks, or conversely, were simply part of the whole fake BW campaign. This seems highly unlikely. For one thing, the content of the intercepted communications is too varied. At least one of the reports describes the North Koreans rejecting faulty evidence of BW attack. Some of the material concerned how to respond to the attacks, with one unit asking for DDT, while other units asked about vaccinations. Some communications report there are no infections from a particular BW bombing, while other reports mention instances of illnesses or deaths connected to the attacks.

It strains credulity to believe that such a variegated presentation as those that make up the current collection of COMINT BW material would have been concocted to fool people about U.S. use of germ weapons, then hidden in encrypted military messages, when there was no apparent reason to believe the U.S. could intercept and interpret these messages anyway. U.S. intelligence sources have said the Koreans and Chinese were always changing their codebooks, and that there were times the U.S. was “flying blind” in regards to their ability to intercept Communist military communications. See my discussion.

Not reproduced for this article, the following link goes to a table listing all biological weapons attacks documented in the COMINT documents. The table appears towards the end of the linked article. A PDF of the full set of BW-related COMINT documents is linked here.

A Propaganda Hiatus?

One major claim of the “hoax” documents — both the twelve documents from 1998 and the Chinese-language Wu Zhili “memoir” (to be discussed in Part 3 of this series) — is that after the attempt to falsify BW evidence was (supposedly) exposed internally within the Communist Party in Spring 1953, the Soviet Union stopped publicly pressing their charges about U.S. biological warfare. One of the twelve documents said that North Korea also stopped publishing on the BW charges against the Americans at the beginning of 1953. Neither of these assertions is true.

In his 18 April 1953 “explanatory note” to Beria, Razuvaev allegedly wrote, “From January 1953 on, the publication of materials about the Americans’ use of bacteriological weapons ceased in the DPRK. In February 1953 the Chinese again appealed to the Koreans regarding the question of unmasking the Americans in bacteriological war. The Koreans did not accept this proposal.”

Another purported document brought forward by Milton Leitenberg, the Wu Zhili “memoir” (to be discussed in Part 3, the final chapter of “Debunking the Debunkers”) vaguely states that China, too, stopped mentioning BW charges sometime in late 1952 or early 1953. It’s comedic to see Leitenberg wrap himself up like a pretzel, maintaining that the Chinese kept telling the North Koreans to publicize the BW attacks at the same time as China supposedly had ceased mentioning such attacks.

But a robust documentary record from numerous sources clearly shows that the Soviets, the DPRK, and China did not cease making assertions about U.S. use of germ warfare throughout the entire Korean War and for years afterward (though the Soviet Union did make some equivocal or contradictory statements over the following decades). Moreover, none of these countries (including post-Soviet Russia) have ever stated the charges were false or disproven.

What are the facts contradicting the supposed cessation of Communist BW propaganda? One example of North Korean propaganda concerning U.S. germ warfare, post-January 1953, is cited in a CIA intelligence report, “BW and the Korean War,” dated 27 February 1953, and released as part of the CIA’s Baptism by Fire document release. This intelligence report described ongoing North Korean statements about the U.S. germ war continuing well into 1953. The report read, in part (italics added for emphasis):

Pyongyang's own contribution to the upsurge in atrocity charges appears in the form of a "Fifth Communique on Atrocities Committed by the American Aggressors and the Syngman Rhee Gang." The communique, also broadcast by Moscow and Peking, reviews the record of U.S. atrocities, listing them in the following categories: destruction of urban and rural areas through bombing; use of weapons for wholesale massacre; i.e., poison gas and BW; and the destruction of cultural and social installations, again through wanton bombing. A long compilation of alleged incidents is used to document each charge. Although no appeal is made to the UN for condemnation of these atrocities, Pyongyang once again calls for a "people's trial" of the responsible criminals." (Baptism by Fire, 2013, 1953-02-27.pdf, italics added for emphasis)

U.S. news articles from that period also belie the claims that the USSR, North Korea, and China, stopped making germ warfare charges in early 1953. For instance, on 23 March 1953, the United Press news agency reported, “radio Peiping charged today that American planes made 60 germ warfare missions over North Korea between January and mid-March” [8]. Additionally, Endicott and Hagerman (2001, see endnote [2]) have described Soviet efforts to bring up the BW charges in the UN in October 1953.

Even more significant was China’s November 1953 release of nineteen depositions by U.S. Air Force flyers, including that of Air Force Col. Walker Mahurin, confessing to use of biological weapons in bombing runs during 1952-53. Mahurin’s deposition also described him visiting Ft. Detrick and being briefed about ongoing germ war research in November 1950. The nineteen confessions were published in English in a Supplement to People’s China in December 1953.

The publication of the nineteen confessions belies claims that China had foregone publicizing the germ war charges by early 1953.

The POW/flyers’ confessions caused a huge stir in the West. On 19 November 1953, the CIA internally discussed the flyer confessions in a report sent to its Foreign Broadcast Information Service. With the subhead, “Peking Opens New BW Barrage,” the CIA analysts wrote:

Widespread broadcasting of the new confessions is being accompanied by vehement support propaganda which largely reviews past evidence, reiterates old accusations about the plans and purposes of the U.S. action, and asserts that these new revelations represent further irrefutable proof against current American denial…. Pyongyang also gave heavy play to the new confessions…. (Baptism by Fire, FBIS reports, 1953-11-19.pdf)

Neither Leitenberg nor Weathersby referred to any of these issues in their work on the Korean biowar charges. Leitenberg himself has doubled down on his assertions over the years, and in the process has produced many misstatements of fact. As recently as 2008, ten years after his initial essay on the Soviet “hoax” documents, Leitenberg stated in a book chapter to Terrorism, War, or Disease? Unraveling the Use of Biological Weapons, regarding the famous claim that BW-tainted insects were found in the snow in January 1952, "It was also the wrong season for anyone to attempt insect-borne BW: it was winter in the area. The reports stated that insects were found on snow, but there they would simply freeze and die” ([9], pg. 6-14].

If Leitenberg meant to falsify or ridicule claims about the insect attacks, he failed. In Factories of Death (p. 104), Sheldon Harris described how Japan’s Unit 731 conducted field trials on plague using fleas in Jilin Province in China during the winter of 1942, killing 300 people and making hundreds more ill [10]. As Leitenberg has noted more than once in his writings, both China and North Korea accused the United States of operating with the assistance of former Unit 731 personnel in their Korean War BW campaign.

In any case, winter BW attacks using insect vectors was not bizarre, as Milton Leitenberg would have the public believe. In January 2024, I wrote an entire article debunking that aspect of Leitenberg’s “hoax” argument.

There are many other highly questionable errors of omission and commission made over the years by both Weathersby and Leitenberg. They range from the absurd, such as the assertion in Razavaev’s document that ants cannot be carriers of disease – a total falsehood allowed to stand untouched by both Wilson Center scholars – to the scandalous.

An example of the latter is Leitenberg’s touting of Hungarian journalist Tibor Meray’s writings, republishing without comment Meray’s ignorant claim that it is “IMPOSSIBLE TO START A BACTERIOLOGICAL ATTACK BY MEANS OF FLIES,” as well as other supposed refutations of the likelihood of using insect vectors for biological warfare (Leitenberg, 2016, p. 48, all caps in original — see endnote [1]).

I have already dissected Meray’s “evidence” and claims before. As for flies and bacteriological warfare, I have previously shown that research using fly vectors was a significant component of Canada’s BW program in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Canada was a major partner with the U.S. and United Kingdom on research efforts on biological warfare. The three countries shared research findings and testing facilities.

— To be continued —

In Part Three of this series, I will look in some detail at a supposed essay by a Chinese doctor-administrator from the Korean War, Wu Zhili. The essay was introduced to Western readers in 2016 by Milton Leitenberg and The Wilson Center. Wu calls his country’s BW charges in the Korean War a “false alarm,” and makes a bunch of incredible claims. Not surprisingly, the essay is as tendentious as the alleged Soviet archival documents analyzed above. But in this case, we can’t blame Beria for its existence.

Subscribe if you don’t wish to miss notice of the publication of Part Three!

Endnotes

[1] See Powell, T. (2018), ‘On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis’, Socialism and Democracy, (32)1, p. 1-22; and Leitenberg, M. (2016) China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War, CWIHP Working Paper #78, March 2016, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. [Online] Available at link. Accessed 14 March 2025.

The original publication of the purported twelve Soviet archive documents was in Weathersby, K. (1998) “Deceiving the Deceivers: Moscow, Beijing, Pyongyang, and the Allegations of Bacteriological Weapons Use in Korea,” CWIHP Bulletin #11, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Winter 1998, pp. 176-185. This article was paired with Leitenberg, M. (1998a) “New Russian Evidence on the Korean War Biological Warfare Allegations: Background and Analysis,” CWIHP Bulletin #11, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Winter 1998, pp. 185-199. [Both available online] Available at link. Accessed 14 March 2025.

[2] See Endicott, S. and Hagerman, E. (2001), ‘Twelve Newly Released Soviet-era “Documents” and Allegations of U.S. Germ Warfare During the Korean War,’ Asian Perspective, (25)1, pp. 249-257 [Online], Available at link. Accessed 14 March 2025. Also see Chaddock, D. (2013). This Must Be the Place: How the U.S. Waged Germ Warfare in the Korean War and Denied It Ever Since. Seattle, WA: Bennett & Hastings Publishing; and Powell, T. (2018), ‘On the Biological Warfare “Hoax” Thesis’, Socialism and Democracy, (32)1, p. 1-22.

[3] Forged documents relating to the Korean War are not unknown. In his three-part history, The Origins of the Korean War, Cumings described a document, supposedly from Stalin’s Secretariat, describing a 10 June 1950 meeting between Stalin, Kim Il Sung, and others, in which a plausible argument was advanced for a DPRK invasion of South Korea. Cumings concluded it was a forgery by South Korean nationalists. (Cumings, B. (1990). The Origins of the Korean War. Vol. II, The Roaring of the Cataract 1947-1950. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 560-561).

[4] Commission of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (1952), Report on U.S. Crimes in Korea, March 31, 1952 [Online], pg. 1. Available at link. Accessed 2 December 2020.

[5] Chaddock (2013, see [2] above) found other inconsistencies in the Weathersby documents, notably the fact the supposed creation of the “two false sites” is said at one point to be before the IADL arrived in early March 1952 (Document #5), while another document from Glukhov (Document #2), stated the “two false areas of exposure” were created three to four months later, before the delegation of the International Scientific Commission arrived in June 1952.

To make matters worse, upon re-examining the Weathersby and Leitenberg documents for this Substack series, I discovered that in Razuvaev’s letter to Beria, he stated that the “second international delegation,” that is, the International Scientific Commission led by UK scientist Joseph Needham, visited China but “didn’t come to the areas of North Korea since the North Korean exhibition was set up in Beijing” (Document #4, pg. 181 in Weathersby, 1998). In fact, as shown in the ISC report, Needham and the other investigators did make a dangerous trip to North Korea, where they interviewed four U.S. POW flyers in August 1952. Why didn’t Leitenberg or Weathersby at least remark on this? The answer can only be they were so biased they couldn’t see the disconfirming information in front of them, or they were terribly sloppy, or they deliberately kept silent about such problematic issues.

[6] Commission of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (1952b), Report on the Use of Bacterial Weapons in Chinese Territory by the Armed Forces of the United States, 2 April 1952 [Online]. Available at link. Accessed 2 December 2020.

[7] For churchmen and missionary evidence, see Dr. Rev. James Endicott’s pamphlet “I Accuse” (1952), Peace Review, Special number published Summer 1952 by the Canadian Peace Congress [Online], Available at link. Accessed 11 March 2025.

See also Rev. Hewlett Johnson’s pamphlet “I Appeal,” undated, but likely August 1952, Britain-China Friendship Association [Online] Available at link. Accessed 11 March 2025. Johnson’s pamphlet contained testimony from clergymen, including an Anglican bishop, and letters from a number of both Protestant and Catholic clergymen protesting the use of BW, and testifying to the truthfulness of those clergymen who had witnessed the use of BW.

The primary journalist eyewitness account of BW is that of Australian Wilfred Burchett (1953), “The Microbe War,” Ch. 17 in This Monstrous War, Melbourne, Joseph Waters, pp. 306-327, [Online] Available at link. Accessed: 11 March 2025.

An account of the controversy over Burchett’s charges is given in Miller, J. (2008). “The Forgotten History War: Wilfred Burchett, Australia and the Cold War in the Asia Pacific,” Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, (6)9, 1 September [Online], Available at link. Accessed 11 March 2025.

[8] United Press (1953), ‘New Germ Charges,” The Honolulu Advertiser, 25 March, p. 2.

[9] Leitenberg, M. (2008) “False Allegations of U.S. Biological Weapons Use during the Korean War,” Chapter 6, in A.L. Clunan, P.R. Lavoy, and S.B. Martin, eds., Terrorism, War, or Disease? Unraveling the Use of Biological Weapons, Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, May 2008. Accessed 11 March 2025.

[10] Harris, S. (2002). Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-45 and the American Cover-Up (rev. ed). New York: Routledge.

Note: This series is adapted from my essay, “‘The enemy dropped bacteria’: CIA Korean War Daily Reports Affirm Allegations of U.S. Germ Warfare,” published at The Journal of American Socialist Studies, No. 3, 2024.

Jeff,

This is another tremendous expose article on the US's criminal use of bacteriological war in Korea and China. The Russian Dossier is a completely fraudulent collection of supposedly secret Russian communications from Laventi Beria, who was a known murderer and pedophile. Stalin did not trust him to be alone with his daughter. The authenticity of Leitenberg's documents, which are translations of copies of copies, has never been independently verified by other scholars. Weathersby's authentication of these copies which possess no identifying marks, was based on credibility to her alone. The Woodrow Wilson CWIHP, a CIA funded think tank, has purveyed these documents around and cowed US Cold War scholars into docile acceptance, or face exclusion from grants, prestigious appointments, and publication.

I have also written extensively on the Russian Dossier, and I have pointed out many other inconsistencies in the construction and internal logic of the dossier in my book, The Secret Ugly: The Hidden History of US Germ War in Korea. My conclusion from studying the known facts and through literary analysis is that the Russian Doddier is a ficticious work based on some CIA evidence and much speculation. I believe it was composed in-house by the late CIA Russia specialist, James Millar.

Regarding the Wu Zhili attribulated essay which you promise to address next, this is an even sloppier fictious work. Wu Zhili was a prolific author with a highly spartan, even terse writing style. The essay attributed to him not only contradicts his earlier written assessments of the US BW war; it is completely rambling diatribe inconsistent with his well-know writing style. I look forward to reading your analysis of this evidence.

Tom Powell