Debunking the Debunkers, Part 3: The Purported Memoir of Dr. Wu Zhili

Archival sources, expert commentaries & internal inconsistencies demolish key document's claims that U.S. germ warfare during the Korean War never happened

The human fleas infected with bacteria which have been dropped on the already ruined land of Korea today, may fall upon the homes of their own countries tomorrow. — “Memorandum on Certain Aspects of Japanese Bacterial Warfare,” Dr. Chen Wen-Kuei, July 1952 [From 1952 Report from the International Scientific Commission for the Investigation of the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in Korean and China, PDF pg. 241]

This is the third part of a series. Each part can be read independently, but are best appreciated read in full. Part One, “Prelude to a Frame-up,” examines the background to the controversy over the issue of U.S. use of biological weapons (BW) during the Korean War. It compares and contrasts the background of two of the primary sources used to prove or disprove the veracity of the germ warfare claims.

The first of these sources is a group of purported Soviet documents, gathered by feared Soviet security minister, Lavrenti Beria, which claim to chronicle efforts to construct false sites of BW attack. These Soviet-era documents are championed by arms control expert, Milton Leitenberg.

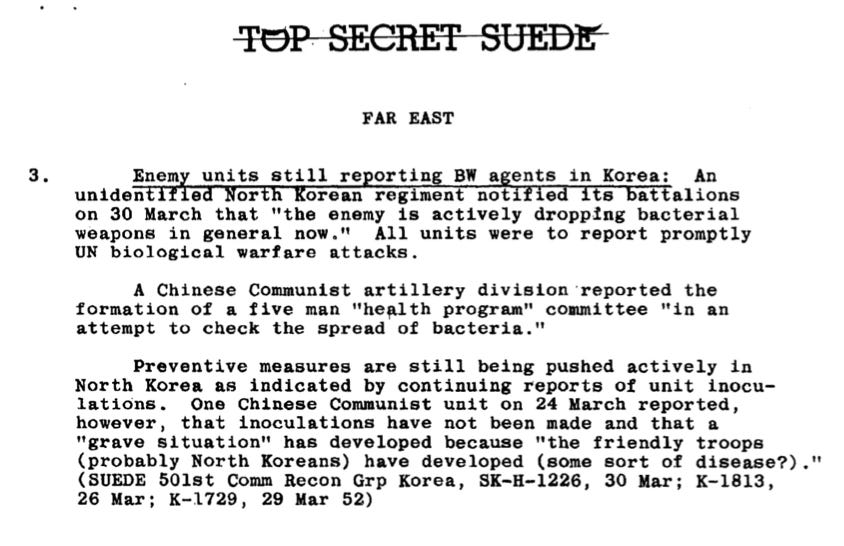

The second group of documents consist of two dozen declassified CIA intelligence reports that quote numerous U.S. Armed Forces’ decrypted communications between Chinese and North Korean military units as they describe their reaction to U.S. biological weapons attack. Combined with the evidence from contemporaneous investigations and declassified documents from U.S., Canadian, and UK government archives, in addition to depositions from U.S. airmen held prisoner during the war, these CIA reports provide striking proof of U.S. use of biological weapons during the Korean War.

Part Two of the series, “Anatomy of a Plot,” examines an alleged documentary record from the archives of the former Soviet Union pertaining to a supposed Communist conspiracy to fake evidence of biological warfare. These Soviet-era documents cannot withstand the most basic critical analysis. The failure of mainstream historians and journalists to critically examine this evidence has led to it becoming the predominant evidentiary base for the cover-up of a most serious war crime.

In Part Three below, I comprehensively examine yet another piece of problematic, if not fraudulent, evidence, a short memoir written by a former Chinese military health official. This document has been used by Cold War scholars and mainstream media to back the U.S. government’s contention that there was no use of biological weaponry during the Korean War. In the end, this memoir, of dubious origin, will prove to be incoherent, self-contradictory in its assertions, and wrong on the facts.

In 2016, Cold War historian and arms control specialist, Milton Leitenberg, whose critique of Communist claims that the United States used biological weapons (BW) during the Korean War are examined in parts one and two of this series, released a new document of “an unprecedented nature on the subject” (Leitenberg, PDF, pg. 10). The document was a newly discovered essay (posthumously published) of a Chinese military eyewitness to the events leading to China’s claims of U.S. use of biological weapons in the Korean War.

This new essay, “a memoir by Wu Zhili, Director of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army Health Division during the Korean War,” would, Leitenberg pronounced, prove the Communist BW allegations were “false” and “that there was no use of biological weapons by the Americans in the war.” Such charges were, Leitenberg further maintained, “a grand piece of political theater” (Ibid.).

But in fact, as this article will demonstrate, Wu’s essay, which probably is a forgery, presents equivocal evidence on the subject of germ warfare. On one hand, Wu asserted that no evidence of biological agents was ever found by Chinese investigators. The threat of possible U.S. bacteriological attack was labelled a “false alarm.”

Yet in another part of the same essay, Wu stated that plague, anthrax and salmonella were discovered in specimens brought to Army investigators from “the field,” where they were said to have been dropped by U.S. war planes. According to Wu Zhili, infectious agents of the type used in biological weapons were found on fleas, tree leaves, and dead fish lying on hillsides. This included evidence of the presence of anthrax, plague and salmonella, and very likely, cholera, as will be shown below.

Before I proceed further in regards to Leitenberg’s claims regarding the Wu Zhili memoir, I wish to take us back in time so that the events in question can be presented in some context. Below are accounts of U.S. biological weapons attack on two villages in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in March and April 1952. These attacks are mentioned in both Wu’s “memoir” and in an investigatory report by the International Scientific Commission to Investigate Bacterial Warfare, headed by world-famous British scientist, Joseph Needham. These two incidents will be used later in this article to compare Wu’s account of events with those documented by the ISC.

Following a look at those incidents, I will introduce Wu’s essay and provide a summary of his claims, followed by a review of the work of three important scholars who have already made critical studies of Wu’s “memoir.” The second half of this article will be an examination of the narrative errors, confusion, and misstatement of facts I find most egregious in the Wu document. My conclusion is that Leitenberg seriously overstated the essay’s credibility. The Wu “memoir” is grievously flawed, is probably a forgery, and cannot be used to discredit the charges of U.S. biowarfare during the Korean War.

The Song Dong and Kang Sou Plague Attacks

By 23 April 1952, Chinese forces had been fighting in North Korea for almost one-and-a-half years. On this clear, cool morning, with a fair breeze, around 10:00 am, two young lieutenants from the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (CPVA) forces in Korea went back to pick up some wood they had cut the day before on a sparse, previously plowed hillside, part of Jang-ja-san Mountain outside Hoi-Yang, in the Song Dong district of North Korea. The cut wood was to be used to build shelters.

Lieutenants Ts'ao Ching-Fu and Fang Yuan were surveyors assigned to a topographical, that is, a map-making and geographical intelligence unit of the CPVA. Along with the Korean People’s Army (KPA), the Chinese were fighting the U.S., Republic of Korea, and other allied forces united under the umbrella of the U.S.-dominated United Nations Command.

Twenty-one year old Lt. Ts’ao sat down to rest on a tree trunk. When he looked down, he saw a half-dozen fleas on one of his shoes and on his lower trousers. Alert from earlier government warnings to the issue of insects and reports of biological weapons attacks, he immediately left the area and stripped off his clothes, then he and Lt. Fang went to report on the situation to their unit’s medical officer, Chang Ming-Ch'u.

The three of them returned to the hillside area, which was at least 100 meters from the nearest road or human habitation. Ts’ao and Fang were surprised to find “a very dense mass of fleas” in the same spot that had appeared clear to them the day before. In the very early morning hours, around 4:00 am, an American plane had been spotted circling the area.

“The noise of the plane was quite loud,” Lt. Ts’ao told local investigators. The plane’s appearance was not totally unusual. According to a field report on the incident, the area was “quite near the front and American planes, therefore, often fly over it” (International Scientific Commission (ISC) report, PDF pgs. 348, 352).

As Lt. Ts’ao approached the mass of fleas, some forty or so jumped on his trousers. The medical officer removed them to use as specimens, then the three left and later returned with barrels of gasoline, and with the assistance of a few more helpers, including the military unit’s barber, burned the mass of fleas. Medical Officer Chang was quite precise on the details of their work:

The spot was burnt from the periphery towards the center with gasoline and pine tree branches. We wore masks and had tightened the openings of our sleeves and trousers. We used alcohol to sponge our hands afterwards. When we returned to our quarters, we took baths and changed our clothes. The dirty clothes were soaked in boiling water and our quarters sprayed with DDT. We five also took sulfathiazole for prophylaxis, two tablets each time, three times a day for three successive days. We were ordered to be quarantined for 9 days. A mass health movement was started. All dugouts in the vicinity were sprayed with DDT. (ISC report, PDF pg. 347-348)

According to the contemporaneous report of the local Epidemic Prevention Committee:

Comrades Ts’ao and Fang had stayed about an hour there the day before and had definitely seen no fleas. There was no lairs or holes of animals nearby. No dogs nor cats were seen in the vicinity. An American plane had circled over this place about 4 o'clock in the morning. Assistant Professor Pao Ting-Ch'eng made an on-the-spot investigation and concluded that there could be no other possibility than that American plane had disseminated these fleas. (ISC report, PDF pg. 345)

The fleas formed a dense mass of about 3 to 4 square meters, though the total area of presumed dispersal by the American plane covered an estimated 300 square meters, according to a detailed appendix on the incident in the report of the International Scientific Commission (ISC), a largely Western group of scientists sent by the World Peace Council, at the invitation of the Chinese government, to examine the evidence the Chinese and DPRK governments had gathered as to U.S. use of biological weapons, and to interview witnesses as well.

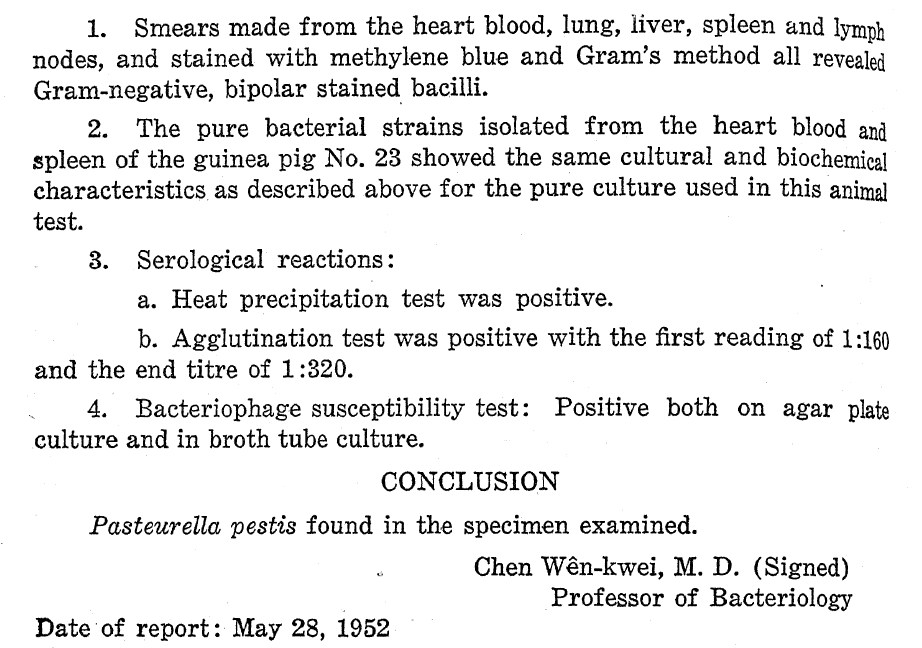

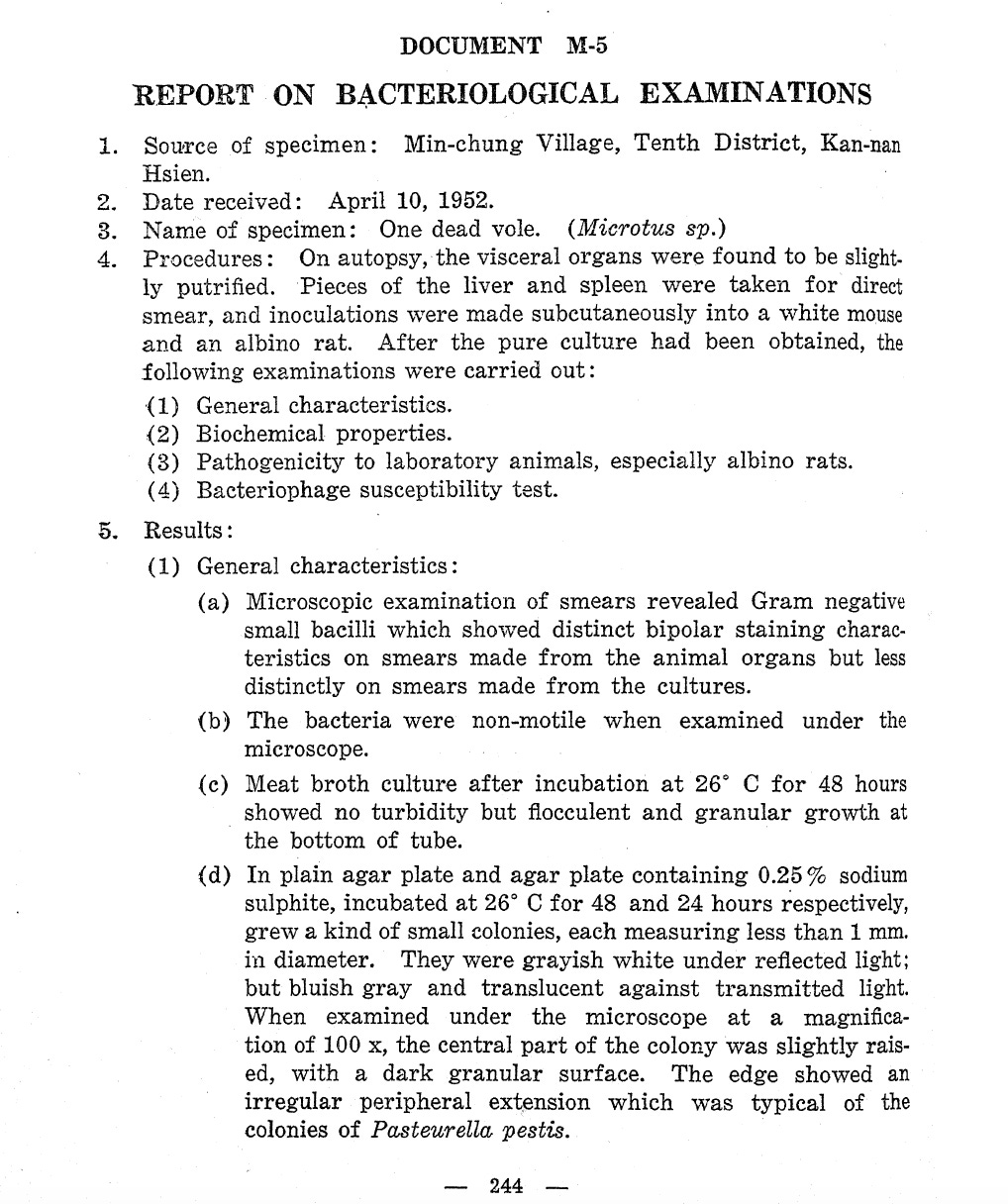

The specimen fleas collected by Lt. Ts’ao were identified as human fleas, or Pulex irritans, aka the house flea, in an entomologist’s report on 4 May. A little over three weeks later, on 28 May, a bacteriological report on the fleas showed they harbored plague virus.

The bacteriological examination consisted of smear and culture microscopic examination, as well as grinding up the fleas and injecting the subsequent emulsion into a guinea pig. The latter was a well-known procedure at the time, “developed by the Sylvatic Plague Committee, appointed by the Western Branch of the American Public Health Association in 1935” (p. 431). While the smear and culture exams did not reveal plague, the guinea pig, which died nine days after inoculation, tested positive, including under microscopic examination, for Pasteurella pestis (ISC Report, PDF pg. 351). The fleas, or some of them, had been carriers of plague.

I direct here the reader to remember that the smear and initial culture examination showed no evidence of plague. We will return to this important point later in this article.

Nearly a month before the Song Dong incident, it was reported that on 25 March 1952, an American plane had also dropped fleas over a village in Kang Sou Goon. The farmer who had discovered the fleas by a local well came down with bubonic plague a week later. He died on 4 April from septicemia associated with the plague.

The North Korean medical officials charged with investigating the situation at Kang Sou had no actual experience with plague. Plague was unknown in their area, and medical experts stated the entire Korean Peninsula had been free of the contagion for hundreds of years. The same claim about the absence of plague virus in Korea was also the conclusion of U.S. military experts. (See endnote 3.)

Hence, local investigators were relieved when Dr. Ch’en Wen-Kuei [modern alternate name, Chen Wengui], the President of the Southwest Branch of the Chinese Medical Association, came to the village to assist investigators there. He had been assigned recently to the Ministry of Health and Epidemic Prevention Service of Korea. When the Song Dong attack occurred, Dr. Ch’en was able to step in to conduct the bacteriological analysis. (See PDF pgs. 325-343, ISC Report; Dr. Ch’en’s testimony is on PDF pg. 341.)

Dr. Ch'en was not chosen merely for his credentials. A little over ten years earlier, he had written a report about a November 1941 plague attack by the Japanese army at Changteh [Changde], which the ISC reproduced in their ISC final report (PDF pg. 220-21) as Appendix K. The Changteh attack was most likely the work of Japan’s infamous Unit 731. While Ch’en documented only 17 deaths in his December 1942 report, Chinese sources say the attack caused an epidemic that ended up killing 7,000 people in the area.

U.S. historian Jeanne Guillemin has written, “In the years 1940–43, Japan’s military attacked Chinese cities and towns with plague, cholera, typhoid, dysentery, anthrax, glanders, and other lethal diseases. By some reckonings, the Japanese program, including recurring plague epidemics, caused hundreds of thousands of deaths and casualties.” But the U.S. saw that none of the Japanese scientists and military involved were prosecuted for war crimes. In 2022, China Daily published a well-documented review of the entire episode, including statements from a number of U.S. historians.

Dr. Ch’en believed something like the Japanese attacks had occurred in the DPRK villages in question.

Meeting Dr. Wu

By the end of July 1952, ISC investigators had made their way under dangerous conditions, including U.S. bombardment, to the DPRK capital, Pyongyang, in order to investigate first-hand the evidence of some of the biological warfare attacks alleged to have occurred in North Korea. On 30 July, they interviewed witnesses associated with the Song Dong plague attack.

The witnesses’ testimony is described in Appendix T of the ISC report, along with the Report of the Local Epidemic Prevention Committee (part of which is reproduced above); a report from the bacteriologist, Ch’en Wen-Kuei; an entomologist report from Professor Ho Ch'i, who had been assigned temporarily to the Korean Epidemic Prevention Corps; and a “field report” filed by Assistant Professor Pao Ting-Ch'eng.

Field work under the conditions of the Korean War was dangerous, and the scientists involved were courageous. By the end of September 1952, when the ISC was filing its final report, three Korean bacteriologists had already “perished while carrying out their professional duties” (PDF pg. 7, ISC report).

The ISC investigators, which included famed British scientist and historian, Joseph Needham, also interviewed the CPVA’s Director-General of Medical Services, Dr. Woo Dji-Lee (according to the transliteration spelling found in the English version of the ISC report). Dr. Woo showed the ISC team a map of the area where the fleas were found (reproduced earlier above). He further indicated, according to the ISC summary of his account, that the “zone of maximum concentration of the fleas was around the SSW centre, as would be expected if some container had emptied its contents mostly there while travelling NNE with some residual velocity” (ISC report, PDF pg. 356).

In other words, a plane had dumped the fleas as it flew over. Additionally, Woo indicated, “There was no trace of any container, however, to be found in the neighbourhood” (Ibid.). The lack of any bomb casing or container was not unusual, as it’s reported that the U.S. used “self-destructing paper cylinders” to drop infected insects, and sometimes also sprayed insects directly out of their planes (see ISC report, PDF pg. 133).

At one point in his essay, Wu does mention reports of the distribution of insects via “paper parachute tubes used for spreading propaganda material” (Leitenberg, 2016,, PDF pg. 74). Since no bomb crater or material was discovered, it’s likely that either spray or self-destructing paper tubes were used at Song Dong.

Sixty-four years after the events it describes, the memoir by Dr. Wu Zhili — aka Dr. Woo Dji-Lee — was presented in English translation in a monograph by Milton Leitenberg, published by the Wilson Center’s Cold War International History Project (CWIHP). The monograph, published in March 2016, was titled China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War (see full PDF).

Wu Zhili’s essay, published as Document #19 in the CWIHP monograph (pgs. 65-73), is about eight pages long. It begins with a bang:

It has already been 44 years (in 1997) since the armistice of the Korean War, but as for the worldwide sensation of 1952: how indisputable is the bacteriological war of the American imperialists?

The case is one of false alarm. [Link, PDF pg. 73, parenthesis in original]

Wu’s judgment of the situation was based upon the supposed lack of empirical evidence when it came to biological warfare. Wu wrote:

My personal analysis was: (1) Imperialism is capable of carrying out all manner of evils, and bacteriological war is not an exception. (2) Severe winter, however, is not a good season for conducting bacteriological war. When the weather is cold the mobility of insects is weakened, and is not conducive to bacteria reproduction. (3) Dropping [objects] on the front line trenches, where there are few people and sickness does not spread easily, and where the U.S. military’s trenches are not more than ten meters away, allows for the possibility of ricocheting. (4) Korea already had an epidemic of lice-borne contagious diseases. All the houses in the cities and towns had been burned down, and the common people all lived in air-raid shelters. Their lives are already difficult, but the Korean people are extremely tenacious and bacteriological warfare cannot be the greater disaster that forces them to surrender. (5) Our preliminary investigation still could not prove that the U.S. military carried out bacteriological warfare. [Link, PDF pgs. 75-76, brackets in original]

Wu goes on to chronicle his ostensible participation in an effort to manufacture false evidence of germ warfare, his fraught encounters with Chinese officials about his conclusions on the BW “false alarm,” and his regret about his actions. Much of what he chronicles is nonsense. While some of his statements can be corroborated with other sources of information, other statements can be easily falsified by the documentary record of the period.

Wu Zhili concluded his memoir by speaking ever so briefly and obliquely about his state of mind. “Now that I am an 83-year-old man who knows the facts and is no longer on duty, it is fitting to speak out: the bacteriological war of 1952 was a false alarm,” he wrote [Link, PDF pg. 81].

Stephen Endicott, Edward Hagerman, and Wu Zhili

In his 2016 essay introducing the Wu essay, as well as some other documentary material also published in the monograph, Leitenberg never mentioned that Wu Zhili, whose essay he is introducing and reproducing in English translation, was the same Woo Dji-Li from the ISC report. I learned that from a 2016 essay by the late Canadian historians Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagerman, best known for their 1998 book on The U.S. and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War and Korea (which is still in print!).

Endicott and Hagerman, both ill and in the final years of their lives, never published their 2016 essay, “On Wuzhili’s ‘false alarm’,” though they did make it available online. It is an important work. While they have their suspicions that the Wu document was a forgery or otherwise adulterated, their primary aim was to emphasize how Wu’s claims of exclusive knowledge about the U.S. germ war campaign were woefully untrue.

To back up their claims, as an appendix Endicott and Hagerman posted portions of a 5 April 1952 report from the headquarters of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, “Concerning the Comprehensive Situation of the Enemy’s Bacterial War and Use of Poisonous Gas, 28 January to 31 March 1952.’ I’ve screenshot a section of that report below. Please don’t skip over it, as it should be read.

One thing that stands out in this one excerpt from the CPVA report is that in February 1952, Army investigators did not discover any outbreaks of plague or cholera or other serious diseases in the Army until the end of the month — just as Wu Zhili reported! Wu said his “preliminary investigation still could not prove that the U.S. military carried out bacteriological warfare” (italics added for emphasis). One month later, that was turned around, as the Army had suffered serious outbreaks of plague and encephalitis.

This appears consistent with the findings of the Korean People’s Army investigators. Of the 15 cases they highlighted, at least in the document I have, where investigations of possible germ war attack took place, only two of them came before 26 February 1952, that is before almost the end of February. (The two early outbreaks said to come from BW attack were dated 28 January and 11 February 1952. — See chart in Part Two of this series.) Unless the DPRK or China open up all the archives, or the U.S. were to open their archives on the parameters and execution of the germ war, we do not know in its totality exactly what was discovered when. I have gone with what evidence I have been able to find, and in relation to that evidence, Wu’s “memoir” is clearly an outlier.

Since we do not know exactly the parameters of the U.S. germ war, I have to conclude that to the best of our knowledge, while the captured pilots indicated that the BW air campaign began in January 1952 (or late December 1951), the full force of the BW attacks did not begin until late January or early February. It must have taken awhile for the various outbreaks of disease to be identified and its sources tracked down, especially since there was “total war” chaos all about the countryside. For their part, the DPRK and Chinese governments did not go public with charges of U.S. germ warfare until late February and early March, respectively.

The composition of Wu’s “False Alarm” essay was coincident in time with a trip Endicott and Hagerman had made to China in 1997, part of their research on the U.S. and Biological Warfare book. We have already seen how the publication of their book was concurrent with the publication of twelve purported Soviet documents that supposedly chronicled the construction of Soviet/DPRK sites of fake BW contagion (see Parts One and Two of this series).

In their essay on Wu Zhili, Endicott and Hagerman stated that while in China they tried to meet with Wu.

Wu “agreed over the telephone to meet,” the Canadian scholars wrote, “but said that (to avoid misunderstandings with his unit) we should first get in touch with its foreign affairs office. We did this through our host, the State Archives Bureau, but without result” (“On Wuzhili’s ‘false alarm,’” pg. 1, parentheses in original).

After our call, Dr Wu, a graduate of Shanghai Medical College in 1937, apparently sat down at his desk to compose a short essay about events of 45 years earlier under the title ‘The Bacteriological War of 1952 is a False Alarm.’ His essay was dated September 1997. [Ibid.]

Endicott and Hagerman were apparently frustrated by Wu’s failure to meet with them. “Instead of showing his essay to us, Wu put it in a drawer where it apparently lay for sixteen years, long after his death in 2005,” they said (pg. 2).

The Canadians went on to give their critique of the Wu manuscript. They relied mainly upon archival evidence and interviews they had themselves gathered in both China and the United States. There is not room to regurgitate every point they made, but one of them is worth repeating.

Endicott and Hagerman emphasize that there were a number of other sources of information about the BW attacks which “Wu Zhili in his headquarters at Songchou may not have been aware of: i.e. ‘Daily Reports’ and ‘Research Group Reports’ from the Northeast Epidemic Disease Prevention Committee and the Northeast Patriotic Health Campaign Committee of the Northeast Administrative Committee, reports which are preserved in Volumes 38 and 43 of the relevant permanent collections at the Liaoning provincial archives (of which we read more than fifty and discuss in chapter 1 of our book); reports from the Logistic Departments along the transportation routes, and from the headquarters of the CPVA in the combat zone.” (See link, pg. 8).

The two historians concluded:

After carefully reading the English translation we have come to the conclusion that although the essay suggests a blip in the historical narrative and gives a strong hint about different currents of opinion among Chinese senior military and political leaders on the topic, (whose origins and reasons will undoubtedly become clearer with the passage of more time) it does not change our understanding about the existence of a large-scale field experimentation with bacteriological weapons by the United States in Korea and China during the Korean War years 1952-1953 — an action which we continue to believe the world, for its own sake, should recognize and condemn as a grievous international war crime. (Ibid., pg. 2)

In my opinion, as devastating as Endicott and Hagerman’s critique was, these dedicated Canadian scholars were really too kind to Wu, or to those who might have forged his “memoir.” As I will show, Wu’s account is wrong factually, and preposterous in many of its various assertions. In more professional lingo, it lacks internal reliability and external validity. Its provenance is problematic. It is a worthless document. In the next section, I will review another modern critique of Wu’s essay.

Powell’s Critique of the Wu Zhili “Memoir”

The other important scholarly work addressing the claims of Wu Zhili’s paper is Tom Powell’s 2018 essay, “On the Biological Warfare ‘Hoax’ Thesis,” published in the journal Socialism and Democracy (Vol. 31, No. 1), which is available online.

Powell’s critique rests heavily on the murky provenance of the Wu essay, and on aspects of the document that point towards understanding it as a clever forgery. Powell also discusses the Wu forgery issue in his recent book, The Secret Ugly: The Hidden History of US Germ War in Korea. (My review of the book can be read here.)

Tom Powell is the son of the journalist and publisher John W. (“Bill”) Powell, who in the early 1980s, exposed the U.S. secret agreement to amnesty the Unit 731 biological warfare criminals. Much earlier, Bill’s reporting on the charges of biological warfare in the pages of China Monthly Review (CMR, which he published) during the Korean War, brought down the repressive apparatus of the U.S. state upon him and his wife and another editor, Julian Schuman, both of whom worked with Bill on CMR. All three, upon their return to the United States, were prosecuted for sedition. Their trial ended with a mistrial verdict in 1959, and the charges were ultimately dropped by the Kennedy administration in 1961. Tom Powell’s book, mentioned above, presents much of this dramatic story. (See also Powell’s essay, “Powell/Schuman Sedition Trial,” as well as my 2021 article, “The Schnacke Affidavit: U.S. Admission of Offensive Germ Warfare Capability During the Korean War.”)

In his Socialism and Democracy essay, Tom Powell begins his examination of the Wu material by recounting the origin of the Wu document itself.

According to Leitenberg’s narrative, this essay was discovered posthumously in Wu’s personal papers, and published in 2013, seven years after his death, in the journal, Yanhuang Chunqiu, an obscure academic publication of the Chinese Academy of Art.31

The first question which arises is the authenticity issue. Is this truly the “memoir” of Wu Zhili? As with the Russian dossier [the 12 Soviet documents I examined in Part Two of this series - JK], once again Leitenberg has produced a critical document with an untraceable origin. Who “discovered” this document? Where is the original manuscript? Is the original written in Wu’s handwriting? Who delivered it to the editors at Yanhuang Chunqiu? Where is the editorial board correspondence which would surround such a controversial topic? Are there any family members or living colleagues who can corroborate the content from personal experience or private discussions with the author? Just like the Russian dossier, the authenticity shadow looms heavy over this document. It seems remarkably convenient that it should appear from a dead author out of an evidence vacuum to fill in the exact blanks necessary to patch together Leitenberg’s hoax thesis.

While Yanhuang Chunqiu may be an obscure academic journal, Western media championed it for its opposition to Chinese “hardliners.” As a 2016 NPR story bemoaning changes in editorship at that time, as the leadership of the magazine came under political pressure, “The magazine, the Annals of the Chinese Nation, or Yanhuang Chunqiu in Chinese, is seen as the standard bearer of the embattled liberal wing of China's ruling Communist Party. The publication has made bold calls for democratic reforms and questions the party's version of history.”

The background to the composition of Wu’s “false alarm” essay seems to come from bureaucratic battles inside China between those who sought greater collaboration or accommodation to the “democratic” West, and those who did not. The Western intelligence agencies leveraged the internal political conflicts inside China to the benefit of the West.

In other words, in both the case of the Soviet archival, Beria documents, and the Wu “memoir,” documents that had an origin within the Soviet Union and China themselves — in Wu’s case, there already was a published autobiographical book — were either manipulated, or selectively edited and/or released in order to factionally impugn the political actors inside both China and the Soviet Union who were seen as responsible for or championing the supposedly bogus germ war reports.

Meanwhile, Western intelligence agencies, who may or may not have been involved in the original attempts to create the bogus documents, used the material created to prop up their own cover-up about U.S. BW use.

There is nothing to indicate that Milton Leitenberg, Kathryn Weathersby, or the translator of the Wu document had any conscious knowledge of or participation in any fraud. My critique of their work is based on what I feel was their preexisting political bias, which I believe compromised an objective analysis of the documents they were presenting. In Leitenberg’s case, his efforts to discredit the BW charges were long-standing, as a future article will document.

In The Secret Ugly, Powell records Leitenberg’s solicitation of historian Sheldon Harris’s assistance in finding some “dissident Chinese military officer to refute the BW allegations” (Kindle edition, pg. 208). Harris was the author of the book, Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-45, and the American Cover-Up, which told the story of the U.S. amnesty of Shiro Ishii and other members of Japan’s BW Unit 731. Powell quotes a 3 April 1997 letter from Milton Leitenberg to Harris, whose book was still in its first edition when Leitenberg reached out:

I have already, through another intermediary, gotten one contact in the (Chinese) Military History Institute — a former senior officer and something of their official repository on the Korean War — and whether anyone else can find some additional path other than through him, I don’t know. What I’m looking for is someone able to describe how the allegation was put together, who (what office, persons) put the story together, coordinated the “evidence” gathering, etc. Someone, someplace in China, has to have such records. I do have a few leads, as I indicated…. The prize would be to locate someone who could say — with substantial direct knowledge — that the allegation was a concoction, and how the decision made to do that was come by, and how carried out. [text from Sheldon Harris Archive, Hoover Institution, Stanford, CA 94305-6010 — The Secret Ugly, Kindle edition, p. 208. Parenthesis in original; emphases in original were underlined words, printed as italics here — JK]

Lo and behold, approximately six months after Leitenberg’s letter to Harris, in September 1997, Wu Zhili put the finishing touches on his recollections of the BW “hoax” as he supposedly lived it, thus fulfilling Leitenberg’s desire for someone with “substantial direct knowledge” of the supposed fabrication of BW evidence to come forward. Then again, it’s possible that, since Wu’s document wasn’t actually published until 2013, September 1997 was simply the date given to a text produced via forgery, a forgery which, Powell explains in his book, was likely rewritten using some portions of Wu’s own published autobiographical writings.

Whether Leitenberg himself solicited Wu’s essay, or did so via an intermediary, I don't know. It’s certainly possible that he had nothing to do with its creation. But it is worth noticing that in his 2016 presentation introducing Wu’s essay, Leitenberg never mentions his 1997 attempts (or any attempts made even earlier) to find a Chinese government source to “describe how the [BW] allegation was put together.” We are indebted to Tom Powell for digging out this truly hidden piece of the historical record.

Leitenberg’s 2016 monograph introducing Wu’s memoir stated flatly that the “False Alarm” essay “was found among his papers after he died in 2008. It was published in a Chinese journal only in November 2013, and an English language translation, arranged by this author, first became available in April 2015” (PDF p. 18). But who found it among his papers? How did it get published? How did it make its way to Milton Leitenberg? He doesn’t say. In any case, by Leitenberg’s account, Wu’s essay took years to wend its way to publication, followed by translation and republication in the West.[1]

The question arises: was the essay even written by Wu Zhili at all? Wu’s 1997 “memoir” is not the only evidence against the Communists’ BW charges that Powell believes originated as a forgery. Powell maintains the Soviet documents mysteriously discovered by a Japanese journalist in the late 1990s, and published by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., were forgeries. The story of these documents, and an analysis of their contents, are recounted in earlier parts of my “Debunking the Debunkers” series.

Powell provides his rationale for the forgery charge in relation to the Soviet documents in both his 2018 essay and his book linked above. I take an agnostic stance on whether those particular documents were forgeries or not. They may have been, or some of them may have been. Then again, the eyewitness statements from Razuvaev, Glukhov, and Selivanov in some of those documents (described in Part Two of this series) may have been forgeries from Beria’s office, adopted in bulk by the CIA or other Western intelligence agencies, and accepted later by historians to whom the documents were leaked. I happen to believe from internal evidence that the Beria-originated statement were coerced by Beria and his repressive apparatus from the individuals involved, via threat or otherwise.

The whole topic is complicated, and while there’s little hard evidence of forgery in relation to the Soviet documents, it remains a strong possibility. Dodging that issue and its related controversies, I decided an analysis of the Soviet documents championed by Weathersby and Leitenberg could be based primarily on their textual matter alone. Whatever their origin, they stood condemned as dependable evidence solely on the grounds of their internal contradictions, errors, and lack of external validity to other known and generally accepted historical sources.

Powell’s conclusion on the Wu Zhili essay is that it is “a complete fabrication and a forgery” (The Secret Ugly, pg. 321). I think with Wu’s document, he makes a strong case. Comparing the 1997 “memoir” with Wu’s earlier autobiographical writing, Powell explains:

[Wu’s 1997 essay] is too verbose, too garrulous with too much US denial mantra. Wu Zhili was a person who did not waste words in his writings. He was efficient to the point of sparse in language use in all he wrote. The two documents are stylistically opposite; they were not written by the same author. Second, Wu Zhili is a trained scientist…. He understands the pathology of disease far better than do the soldiers and political leadership which was why Gen. Peng wanted him present, and he rightfully cautioned patience. Lastly, the term false alarm—in the US the emphasis is placed on the word “false” implying error or perhaps some deliberate mischief. If the emphasis is placed upon the second word “alarm,” a nuanced meaning of this phrase arises, such as “much ado” or a “needless panic.” The US attack began in the dead of the Korean winter when the ground was frozen and covered in snow. The contaminated insects emerged from their containers moribund and easily destroyed. The US strategy of germ war was telegraphed long before weather conditions became favorable. What the medical experts He Qi and Wei Xi cautioned against was over-reaction and public panic. It is this caution, this time delay recommended by Wu Zhili and the two Chinese experts to get the facts right that the Hoax thesis wants us to believe is when deliberate fraud occurred. [Powell, Thomas. The Secret Ugly: The Hidden History of US Germ War in Korea (pp. 322-323). Edgewater Editions. Kindle Edition.]

A Questionable “Memoir”

I now wish to direct the reader to my own extended analysis of Wu’s 1997 narrative, which, fraudulent or not, has the same problems as the purported Soviet archival documents.

The supposed Wu “memoir” is so full of lies, half-truths and confused statements that it will take some time and patience to sort it all through. It is a necessary task, however, as the Wu essay is a central component of the U.S.-Western cover-up of the BW war crime, the preponderance of the evidence of which shows the U.S. did engage in germ warfare. Making an accusation about a war crime as serious as biological warfare means that a full, critical analysis of the evidence gathered (or manufactured) against the actuality of such a crime is crucial in assessing the truth.

As with my examination of the “twelve Soviet documents” in Part Two of this series, my own analysis of the Wu essay rests heavily on textual analysis of its internal reliability and external validity. Regardless of whether or not the Wu essay was a forgery, a solicited memoir from a Cold War scholar, a misremembered piece of history by an old man decades after the fact, or whatever, the essay fails as a truthful historical narrative on a number of counts, based upon what it actually says or claims.

Wu’s essay presents a false and at times terribly conflicted chronology of events, contradicts itself in relation to the evidence, minimizes the scientific approach of the experts who examined the charges of biological warfare, and asserts evidence that is clearly rebutted by an indisputable historical record. I enumerate these points in the following sections.

Vague Sequence of Dates

The first thing that struck me was how Wu’s paper is terribly vague or wrong regarding dates. For instance, Wu attributes a cholera attack in Daidong (Dai-dong), North Korea, to “the day the [ISC] hearing began,” which would identify the attack as on or around 23 June 1952. However, the ISC report dates the attack over a month earlier, on 16 May 1952, and produces documentary evidence for that date.

Similarly, Wu dated an incident when a family found fleas floating on a water jug near their house as also occurring at the time of the ISC hearing (late June). This incident is also described in the ISC report and dates back to late March (See Appendix R of ISC Report, “Report on a Case of Plague in Kang-Sou Goon, Pyong-An-Nam Do, by Contact with Fleas Infected with Plague and Dropped by a U.S. Military Plane on March 25, 1952,” PDF pgs. 325-339.)

Oddly enough, it was Wu himself who briefed the ISC on a suspected drop of plague-infected fleas on a hillside near Song Dong, Hoi-yang Goon, North Korea, which the ISC documented as occurring on 23 April 1952. (See PDF pg. 344 of ISC Report.) The Song Dong attack is described in the initial part of the present essay, and in the section “Meeting Dr. Wu” above. The fact that Wu was personally involved in the documentation of that incident is never mentioned in Wu’s supposed written account. Leitenberg, introducing Wu’s document to the Western world, never mentioned it either. That seems quite odd. In any case, in his “false alarm” essay, Wu never provided any date at all for the Song Dong episode. We can infer from his narrative that he is indicating it must have come prior to when the ISC conducted its investigation, i.e., before 23 June.

Incredible and Egotistical Claims

Sometimes Wu makes fantastical claims, as when he said he offered to infect himself with bacteria and thereby martyr himself in order to provide “proof” of biological warfare to international investigators. By Wu’s own account, worried that there was no evidence of use of germ warfare, he told the “deputy captain of his disease prevention unit,” Li Zhefan, “In case it will be difficult when the time comes to prove bacteriological warfare, inject me with plague and let me die. This way, the director of the Health Division will have caught the plague dropped by the U.S. military even if it is not ironclad evidence” (Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 79).

This particular assertion seems to say more about the ostensible psychology of Wu Zhili than it does about anything else. In any case, he was talked out of such a bizarre self-sacrifice. But even more, as I discuss comprehensively below, it’s hard to believe that a doctor-bureaucrat like Wu didn’t realize that the epidemiological linkage of plague and any biological warfare attack was not simply a matter of contracting plague. One had to say where it was contracted, how the symptoms were noticed, and what might link such an outcome to presumed U.S. attack. Perhaps that’s what Wu is alluding to when he says his death by plague would not present “ironclad evidence” of BW attack.

Elsewhere, Wu described his anxiety in relation to his opposition to the general support for findings of U.S. BW attack. He wrote that he feared he would be “beheaded” as a result of taking such a position. Referencing what he portrayed as the treacherous politics surrounding the BW charges, he stated, “If I don’t do this right I’ll be beheaded. I should prepare myself to be beheaded” (Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 77).

After a lengthy attempt to find instances when internal political opponents inside the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, or the Chinese Volunteer People’sArmy, were beheaded during the Korean War, I could find no indication that any such beheadings ever took place. It’s true that in recent history of the times, Chinese warlords would sometimes behead traitors or political opponents, but I know of no instances where Chinese communists used such practices, at least during the Korean War. Wu’s statement about fearing decapitation reads like Kuomintang or CIA propaganda.

I did, by the way, discover a picture of South Korean soldiers holding the severed head of a North Korean soldier. I’m not going to reproduce it here, but readers can view it for themselves. The photo, dated 17 November 1952, was taken by the famous American photographer, Margaret Bourke-White, and is part of the LIFE Picture Collection. Whatever decapitations took place, they were not on the Communist side.

Contradictory Claims Regarding Bacteriological Evidence

In his “memoir,” Wu presented the bacteriological work his unit did as central to the identification of bacteriological attack, when in fact, as mentioned earlier, Endicott and Hagerman noted there were a number of units and doctors and bacteriologists involved in this work in both China and North Korea.

Wu wrote that he sent three teams of experts and technicians to “the health departments of the Eastern, Central, and Western fronts…. to take charge of the preliminary examination of specimens sent up from the field” and assist with “disease prevention work (Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 77).

Incredibly, despite Wu’s claims there was no evidence of biological agents found by Chinese military investigators (which was echoed approvingly by Milton Leitenberg), by Wu’s own account his teams did discover some evidence of biological agents. Wu wrote:

The number of specimens received was large (several hundred), and some had bacteria cultured from them. All of these were Salmonella-type, and neither plague nor cholera appeared. A few times anthrax was found on tree leaf specimens. There were all kinds of so-called ‘dropped objects,’ but it was difficult to link them to bacteriological warfare. [Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 77]

Despite the claim that the BW charges were a “false alarm,” in his document Wu said that bacteria indeed were found. Contradicting himself, he stated that “all” the bacteria found were “Salmonella-type,” but then immediately noted that “A few times anthrax was found on tree leaf specimens.” As Endicott and Hagerman said in their Wu Zhili essay, the discovery of anthrax “was a significant finding of a biological warfare technique upon which Wu makes no further comment….” (pg. 6).

Although not as absent as plague, anthrax was not a serious danger to humans in Korea. In fact, U.S. authorities had stated in a 1948 military report that no cases of anthrax in humans had ever been recorded in Korea (see endnote 3). The claim that “all” the specimens found to have bacteria consisted only of Salmonella contamination is patently untrue.

Anthrax spores are generally found in soil samples or on animal products, not on the leaves of plants. While it is possible, I suppose, that a leaf could fall to the ground and somehow pick up an anthrax spore from the soil, the fact that there was more than one specimen with anthrax makes that scenario unlikely. The tree leaf specimens were found from “drops” attributed to American war planes. In his commentary on Wu’s essay, Leitenberg has nothing to say about finding anthrax on tree leaves.

It’s worth mentioning, in addition, that Wu stated that of “several hundred”provided specimens (the time frame for their collection isn’t given), only “some had bacteria cultured from them” (italics added). We don't know what percentage of specimens showed bacterial contamination. Once again, Wu’s vagueness regarding facts is an obstacle to using his essay to prove anything.

As for the presence of Salmonella organisms, the ISC report briefly mentioned the presence of Salmonella bacteria in dead fish that had apparently been dropped by U.S. planes on various hillsides, and that these “always occurred in the neighbourhood of drinking-water sources” (PDF pg. 59).

Salmonella had a history during the Korean War period, and even earlier, of being studied as an agent of possible use in biological warfare. Indeed, in their Wu Zhili essay, Endicott and Hagerman noted (pg. 6) that Salmonella “was one of the debilitating pathogens favoured in the US BW program.” They did not offer any documentation for the claim, but readers can reference this 2011 U.S. Army report on research holdings at the U.S. Army’s Dugway Proving Ground, which records three BW-related Salmonella research studies — see PDF pgs. 136, 143 and 200. Each of these studies is identified as being conducted at the U.S. biowarfare headquarters at Fort Detrick. Two of the three are dated as occurring in 1951 or earlier.

In addition, a 27 June 1950 report (pg. 22) from Canada’s Defence Research Board, [2] which worked in a collaborative fashion with both the U.S. and UK biological warfare programs, asserted in a section on the study of “Insect Vectors” that they had developed “New methods… for determining the carrying capacity of house and fruit flies for pathogenic bacteria.” Furthermore, they found that using baits contaminated with Salmonella appeared to be particularly promising for infecting flies for use in biological attacks. [2]

I have already written about how during the Korean War a huge controversy erupted in Canada over claims that the Canadian government had been assisting the U.S. in its germ war activities in Korea. Hence, the presence of salmonella in Wu’s samples from the field could indeed have been part of the U.S. germ war campaign, though this must remain, for now, speculative. I must say, however, that contaminated dead fish on a hillside, or aimed at a water source, certainly could be classified as a possible instance of a BW-contaminated bait.

Finally, on the subject of what biological agents were discovered, Wu also mentioned that the ISC heard evidence of poisoning by cholera vibrio. He wrote, “American planes dropped straw baskets on Daedong in Pyongyang, which contained mussels carrying cholera. Patients ate the mussels, got cholera, and died. Korea had not had cholera in many years” (Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 77). [3] Wu did not contradict this assertion, though elsewhere in the report he had stated that his investigators had not found cholera in the specimens they examined.

Separate from the above issues, I also wish to highlight the fact that in his narrative, Wu remained silent about the hundreds of eyewitness reports of BW attack, including many who saw U.S. planes dropping different kinds of materials. While he noted that hundreds of specimens were gathered from the countryside, he never spoke of the testimony of the eyewitness accounts. These witness accounts are basically ignored. In this, Wu’s disregard for eyewitness testimony is consistent with Western governments and media accounts of the germ war allegations. The eyewitness attestations are mostly minimized.

(An exception in Western coverage of the germ war, with interviews of eyewitnesses to biological warfare, see Tim Tate’s excellent 2010 documentary for Al Jazeera’s People and Power, “Dirty Little Secrets.”)

It is unlikely that, in his position, Wu was unaware of the early efforts of the Korean People’s Army to establish the facts about the germ warfare attacks. In Part Two of this series, I reproduced a chart from the March 1952 “Report of the Commission of the Medical Headquarters of the Korean People’s Army on the Use of Bacteriological Weapons,” which I copied from the Canadian Peace Congress’s 1952 report, Documentation of Biological Warfare (see pg. 9-10). No bacteria were found in two of the fifteen insect drops documented in that chart. The fact that two of the specimens examined by Chinese and North Korean health officials found no bacterial contamination strongly suggests that the scientific reports involved were not falsified, but represented the differential findings of those examining the evidence first hand.

Why were there uneven findings regarding the biologically contaminated specimens? It is likely that some of the U.S. insect drops were meant to sew confusion and fear, that is, they did not carry bacteria, and had primarily a psychological purpose. Author Nicholson Baker highlighted this aspect of the BW controversy in his book on the topic, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act. (See also my review of the book.)

Other plane drops obviously were meant to spread disease and epidemics. It is also possible, as the ISC report pointed out, that the pathological agents attached to some of the insect drops and other BW attacks, were never discovered or identified.

Considering those instances where no pathogenic material was discovered from suspicious insect drops, the ISC report concluded, “It is a difficult matter to isolate pathogenic micro-organisms from such material when no one knows exactly what should be looked for, all the more so when artificially selected bacteria and viruses are in question. The possibilities are far from having been exhausted” [PDF pg. 59].

Finally, some of the specimens gathered were of bogus origin, and were rightly discarded after examination. The CIA’s communications intelligence reports cited a 25 March 1952 intercept from a North Korean battalion in the Hamhung area. A North Korean military sanitation officer, sent to affirm a supposed biological warfare attack “reported that the policeman’s report was false and that the flies ‘were not caused from bacterial weapon but from the fertilizers on the place.’” (See original CIA document.)

I personally think that the very earliest germ war missions carried many dummy charges, as the tactics, techniques and procedures for operationalizing BW missions had to be tested first in the field, before they went “live.” But I think this phase only lasted probably a few weeks, maybe a month, as the U.S. was anxious to get these weapons into use.

An Unlikely Conspiracy

Wu’s claims about a BW “false alarm” implied a very large conspiracy, one that included dozens, if not hundreds of people, including doctors, scientists, military men, churchmen, and peasants. Wu’s narrative contends that the idea of faking evidence came only after hundreds of reports of dropped materials or insects came into Army investigators, and none of the specimens turned in (supposedly) showed signs of bacterial infection.

Wu implies that due to visits by the IADL and ISC investigatory teams, the Chinese had mere days, or in Wu’s more haphazard account, possibly weeks, to construct a wide-ranging conspiracy. Was it really possible to do this? How did they arrange for the compliance of a number of respected and well-regarded doctors, academics and scientists?

Consider the following list of Chinese doctors and professors who staffed a 1952 Chinese commission of entomologists, microbiologists, parasitologists, and epidemiologists to reexamine and comment upon the evidence gathered by the Korean People’s Army, a Chinese Commission of Inquiry, and the IADL reports on the BW attacks. Are we to believe these distinguished doctors and professors were in league with a hoax about the use of biological weapons?

The commission of experts concluded:

It is apparent in a very convincing manner from all the documents presented, along with the photographic material and the protocols of the epidemiologists and entomologists that bacteriological weapons have been used in Korea and in North East China. [Documentation of Biological Warfare, pp. 13]

Nearly half of the signatories, listed below, were Western-educated, or had responsible positions in Western academic or professional institutions. They had much to lose by sacrificing their integrity to back an outrageous propaganda “hoax.’

"Mr. CHEN SICIEN H., Graduate of Futan University, Shanghai (1928), Doctor of Paris University (1934), Director of the Entomology Laboratory at Sinica Academy, Peking and Joint Director of the University Museum “The Dawn," Shanghai.

"Mr. CHING YAO-TING, Graduate of Cheeloo University (1914), Professor at the Medical College of China, Mukden, and Head of the Biology Department of the Medical Faculty.

"Mr. HSIN CHUN, Doctor of Medicine of the Imperial University of Nogaya (Japan), member of the Institute for the Prevention of Epidemics in the North-East.

"Mr. CHING KWAN-HUA, Graduate of the South Manchuria Medical College, Mukden (1924), Professor and Director of the Department of Bacteriology at the Medical College of China, Mukden.

"Mr. LUH PAOLING, Professor of Entomology at the Agricultural University, Peking.

"Mr. CHU CHI-MING, Graduate of Shanghai Medical College (1939) Doctor of Philosophy of Cambridge University (Great Britain), Chief Consultant of the National Institute of Serums and Vaccines, Peking.

"Mr. LI PEI-LIN, Professor of Pathology at the Medical College of China, Mukden, Doctor of Philosophy of London University, member of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

"Mr. WU CHIH-CHUNG, Professor of Medicine at the Medical College of China, Mukden, Fellow of the Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons, Glasgow (Great Britain)

"Mr. CHANG HSUEH-TEH, Doctor of Medicine of Peking Union Medical College, M.S. of Illinois University (U.S.A.), Professor of Medicine at Peking Union Medical College.

"Mr. HSU YING-KUEI, Doctor of Medicine, former Research Assistant at the Institute of Psychiatry, Munich (1938), Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry at Peking Union Medical College. [Documentation of Biological Warfare, pp. 11-12]

This same Chinese commission also commented on a subject that Wu mentioned in his “memoir.” In explaining why it was unlikely that North Korea was under BW attack, Wu, like many other commentators, pointed out the unseasonableness of the winter cold. “Severe winter,” Wu wrote, “however, is not a good season for conducting bacteriological war. When the weather is cold the mobility of insects is weakened, and is not conducive to bacteria reproduction” (Leitenberg, 2016, PDF p. 75).

Whether or not the mobility of the insects was in play or not — microbes can still live on dead insects or find their way into the soil or water, or into animals who eat dead insects or vegetable matter — the doctors listed above saw the cold weather as evidence that the appearance of the insects at such a time of year was no accident or mere biological oddity. Drawing upon their expertise, the scientists wrote:

It follows from the detailed reports of eminent specialists—experts on the question of insects in these areas—and entomologists, considering the season and the climatic conditions (low temperature of 0 to minus 20 degrees C., and snow) not only at the time when insects were discovered, but also during the preceding weeks, that it is impossible that the insects could have been there by natural means.

This can be proved especially by the discovery of locusts and crickets, Aedes Koreicus, and different types of flies. It is impossible to find at this season of the year these types of insects in such number and at an adult stage (imago). [Link, pg. 12]

Wu gives no explanation for the unusual appearance of the insects, and he misrepresents the bacteriological findings on the insects that were sampled by the specialists. This is in addition to other points I’ve already made. I could simply stop my indictment of Wu’s essay at this point, as it’s quite clear that his narrative (or the narrative published in his name) is corrupt, or at best, confused, but it’s important to document for posterity the full meretriciousness of the Wu “memoir.” Hence, let us continue.

Claims of Falsified Evidence Provided to Professor Chen Wengui Lacks Both Evidence and Credence

Wu implied that the Chinese and North Koreans had manufactured the “evidence” of bacteriological attack, specifically plague virus. He related how plague expert Dr. Chen Wengui [translated as “Dr. Ch’en Wen-Kuei” in the ISC report, as noted earlier in this essay] informed him that plague bacilli had been “lost” from Wu’s “inspection team’s bacteria lab.”

Wu then explained that he collaborated with high Chinese military health officials to have two tubes of plague bacilli, “packed in sealed iron pipes,” delivered from Shenyang, China, to replace the “lost” sample. He then give one of the tubes to Chen Wengui, and the other to the “North Korean deputy prime minister of health protection.”

Wu strongly implied that the North Korean deputy prime minister “knew exactly why I gave him the cultures,” i.e., he was in on the subterfuge (see Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 79). But he had nothing more to say about Chen Wengui. The latter was an experienced, if not celebrated, bacteriologist, and he would have wanted to know where these samples originated, what reports documented the gathering of the samples, etc. Was Wu implying that Chen was part of the conspiracy to present false evidence of biological warfare?

Wu doesn’t go that far. However, he initially stated that Chinese scientist Fang Liang, whom Chinese military authorities had sent to assist in bacteriological analyses of the thousands of specimens sent in to authorities, was aware there was (supposedly) no bacterial evidence of plague. Wu did not say the same about Chen Wengui, which would suggest that Chen, who was working then at the same lab as Fang, and who (supposedly) discovered there were no plague samples, was not part of any conspiracy.

In the end, Wu lets the entire subject sink into narrative ambiguity. He simply dropped the matter about presenting the dubiously obtained plague samples from Shenyang to Chen. It’s not clear what was supposed to happen after that. Such narrative gaps are part of the lackadaisical aspect of all the so-called evidence in the Wu document. Perhaps Wu’s heart was not really in his takedown of the BW allegations.

If one wants to see what kinds of documentation actually accompanied the bacterial lab analyses on possible germ warfare specimens by Chinese scientists, the ISC report is full of such examples. Interested readers can see ISC Report, PDF pgs. 269-277, 349-351, 437-463, and 723-727.

Below is an example of one such bacteriological examination, in this case of a vole dropped by an American plane at Min-chung Village, Kan-nan Hsien, China in April 1952. Notice that the documentation includes the source of the specimen, the date the specimen was received, the identification of the specimen, bacteriological procedures undertaken, the results of testing (including explanation of procedures), the conclusion derived from the test results, the names and professional associations of those involved in the testing, and the date of the report itself. In other words, there’s a lot more to passing on bacteriological evidence than sticking microbes into an iron pipe.

What was Chen Wengui to do with the tube of plague bacillus given to him by Dr. Wu? Where was the accompanying documentation? If there was such documentation, and it was forged, who forged it? When? Why did Wu not mention this? Either Chen was somehow involved in the subterfuge, which Wu seemed to indicate was not the case, or despite his expertise Chen was willing to accept a plague sample with no explanations. None of this tale, such as we have it, seems to make any sense, probably because it never happened.

Contradictory Claims About the Song Dong and Kang Sou Plague Attacks

Wu also provided his version of the Song Dong and Kang Sou plague attacks, with which I began this essay. He stated, regarding what must be the Kang Sou episode, that the “case was of plague deaths: one day a family discovered fleas on the surface of their water jar, which was very strange. After a few days, members of the family fell ill and died. The autopsy revealed plague. Korea had never before had plague.” (See for this paragraph and the two that follow, Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pp. 78-79.)

Noting that the evidence for the Kang Sou case was prepared by “Professor Chen Wengui,” Wu offered no statement or evidence that would contradict the findings in the Kang Sou case.

As for the Song Dong discovery by “two first lieutenants at the 20th Group encampment who discovered a dense group of fleas while chopping wood,” Wu stated that “Plague was cultured from the fleas” the officers sent to be analyzed. This contradicts his claims elsewhere in his “memoir” that no plague or cholera were found in the samples his teams examined. Wu then claimed that he had the two lieutenants lie about where they found the fleas.

The truth of this matter is that the fleas were discovered in small thatched cottages in the forest. These cottages have firewood and other assorted items in them that are suitable for flea colonies. It is difficult to say that the American imperialists dropped these in. When they were giving the above report, they did not mention the thatched cottages. This time when they were asked to go out and testify at the scene, one of them said that Chairman Mao taught him not to lie. He was unable to move. What to do? Only to persuade him to submit to the current needs of the struggle against the enemy and say that the place where fleas were discovered was out in the open. All the flea specimens were human fleas (Pulex irritans). As for the plague, that was easy, we [could] cause it to appear. [Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 79, parentheses and brackets in original]

This could be considered a classic example of conflicting evidence, i.e., two or more individuals offer different versions of a singular event, and there's no other evidence or witnesses to determine what actually happened. Except there is other evidence, as well as other witnesses. There is the report of the bacteriological examination. Also, there is a detailed field report by entomologist Pao T’ing-Ch’eng, who visited the spot where the fleas had been discovered, and also interviewed the lieutenants’ medical officer, Chang Ming-Ch'u. Chang had returned to the presumed drop site with the two officers after they first reported the infestation.

Some people will still prefer Wu’s version of events, constructed decades after the fact, and totally unsupported by any other evidence, over that of the Chinese witnesses. But Wu’s narrative overreaches on two accounts, calling thereby his entire narrative on this incident into question. For one thing, as previously noted, in his “memoir” Wu never mentioned that he was one of the Sang Dong reporters to the ISC when they came to visit the village. His failure to mention his own role in the original documentation of the Sang Dong attack makes one wonder what else he is hiding from his readers.

Also, we have the bizarre contention by Wu that it “was easy” to cause plague “to appear.” Presumably he meant to insert plague bacilli into samples sent for examination. Or perhaps he meant it would be “easy” to falsify the results from a lab.

It’s worth pointing out that if Chinese authorities were going to falsify the presence of plague, they would not have their lab report claim no presence of plague bacilli in smear and initial culturing from the samples. As it turned out, further examination, via injection into a guinea pig of an emulsion made from the ground up flea specimens, was necessary to determine the presence of plague, a disease that was not endemic to North Korea. [See Endnote 3.] (Selections from the relevant lab report are screenshot below.)

. . . .

The finding of plague seems genuine, not planted, as it would have been very difficult to engineer the sequence of results above in the laboratory. If the entire report was a falsification, it seems highly unlikely that the initial equivocal lab procedures would have been part of a falsified narrative.

Finally, as for the “ease” of transmitting plague bacilli, it would have been a highly technical procedure, and of some danger to those engaged in the transfer of such a dangerous organism, as the history of laboratory leaks of bacteriological agents testifies.

False Claims About Lack of Casualties

As another example of the poor evidentiary value of Wu’s supposed memoir, Wu claimed, “For the entire year [1952], no sick patient or deceased person was found to have anything to do with bacteriological warfare” (Wu, 1997/2013/2016, p. 70). But there is plenty of evidence contrary to that assertion. For one thing, the COMINT documents mention “several deaths” from BW attack. Additionally, the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL) report on North Korea mentioned 45 deaths from both plague and cholera (IADL link, pp. 7-9).

The ISC also mentioned both sickness and deaths from bacterial attack. There are 19 specific deaths referenced in the ISC report, other than those that were derived from other sources, such as the IADL report. The ISC-reported deaths are said to result from plague, cholera, anthrax, and encephalitis (See ISC Report, pp. 24, 32-33, 36, 367, 456, 460-469, 617, 619-621). The ISC also noted the presence of BW that killed animals as well (pp. 609-617). The ISC refused to state precise figures regarding casualties, believing doing so “would provide the last essential data for those upon whom the responsibility [for BW] lies.” [ISC report, p. 59, material in brackets added — Note: the pages referenced from the ISC report in this particular paragraph direct the reader to the pagination in the report, and are not the same as the PDF pagination.]

Instead, the ISC concluded, “many human fatalities have occurred in isolated foci and in epidemics, under highly abnormal circumstances in which the trail always leads back to American air activity” (ISC Report, p. 59/PDF pg. 61). In their imprecise or sometimes vague reporting of BW-related casualties, Needham and his associates appeared to follow China and North Korea’s example, as these governments seemed in their own propaganda to usually avoid mentioning the number of BW deaths or illnesses. The U.S. Armed Forces Agency intercepted Communist radio communications about BW attacks, quoted in the CIA’s COMINT reports, also seem vague about the number of casualties, indicating probable operational security restrictions on communications about such information at the time.

If Wu believed there were no deaths from BW, he certainly had to be aware that North Korean and Chinese sources, as well as the IADL and ISC investigations all mentioned some deaths, and numerous BW illnesses. And, again, if not Wu, then at least Milton Leitenberg, who presents himself as a scholar on the Korean War BW accusations, should have said something about this. It is an egregious omission.

Falsely Implying Coercive Interrogation of U.S. Airmen

In his essay, Wu Zhili wrote how the ISC investigators had gone to Pyongyang to hear testimony. Wu portrayed both the ISC and the earlier IADL investigators as essentially fellow-traveling dupes of the Communists. It is a slanderous accusation, and one that later commentators have also argued. But there is no proof that any investigator did anything but their best to find the truth. I encourage readers to read the investigations’ reports and decide for themselves how good a job they think these men and women did. I have copiously sprinkled this article with links to the relevant documents just so readers can do exactly that.

Wu related how after the ISC went to North Korea, they returned to China, but first “they went to Pyoktong prisoner of war camp on the northern border of Korea and met with several U.S. airmen.” These airmen had been earlier quoted “in People’s Daily that they had dropped bacteriological bombs” (Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 80). As surely Wu was aware, when these confessions reached the West, there was a great scandal.

Wu described how some of the Air Force POWs, in discussions with the ISC team, had “freely discussed the classes they took on bacteriological weapons and their experience with ‘bombs that don’t explode’” (Ibid.). The latter was a reference to the fact that the airmen told Needham and his associates that, as regards their after-mission reports to the Air Force, they were to refer to the germ bombs they dropped as “duds,” thereby masking the truth about the bacterial nature of the weapons.

In 1952, the whole question of “duds” briefly surfaced in a political fashion back in the United States. I have postulated elsewhere that some Air Force personnel, disgruntled over the idea of engaging in germ warfare, had fastened onto the “duds” issue in an unsuccessful attempt to expose the BW program.

Of course, Wu’s central point in his memoir was that there had been no germ war bombings. But he had to account somehow for the incriminating testimony of the airmen. Wu claimed that when the Air Force prisoners of war returned to the United States after the war, “they were all disciplined” for their BW confessions to their captors. He then slyly added, “I really admire the persuasion work of our personnel in the prisoner-of-war camps” (Leitenberg, 2016, PDF pg. 80). The implication was that China’s military interrogators had used powerful means of “persuasion,” i.e., coercive methods and/or torture, to get the prisoners to falsely confess.

For more on what the airmen actually told Chinese interrogators about the U.S. biological warfare program, see the linked articles here and here.

Even though Wu had very little to say about the prisoners’ confessions, his narrative on this issue was misleading on two points. One, the airmen were not “disciplined” upon their return to the U.S. While it is true that they were threatened with prosecution if they did not retract their confessions, none of them were actually prosecuted. Other returning prisoners did face prosecution for collaboration with their Communist captors, but none of the airmen did. Nor did the confessing airmen lose rank or otherwise suffer any official discipline.

The one exception was Marine Corps Colonel Frank Schwable, who had been the highest ranking BW confessor in the POW camps. Schwable faced a “board of inquiry” after his return to the United States, but this was not the same as an official court martial. In the end, the Colonel was exonerated of any wrong-doing, and continued his Marine Corps career, albeit he was never to hold an important position again.

The second point where Wu was wrong concerned his implication about undue forms of coercion to “persuade” the airmen to confess. In fact, as I only discovered myself a few years ago, all the airmen involved in biological warfare missions had been specially briefed before hand that, if captured, they were free to talk with their captors beyond any restrictions of name, rank and serial number. This fact surfaced during the Marine Corps’ Board of Inquiry hearing on Schwable, when multiple testimonies declared that War Department brass had given special instructions to BW airmen about how to behave if captured.

On 24 February 1954, Major Walter R. Harris, a decorated Marine Corps aviator and former Korean War POW, who had organized resistance in his POW camp, told the Schwable inquiry panel that before they were deployed, as regards capture, “75 to 80 per cent of the air personnel” in his camp “had been instructed to tell anything you want to.” Another “15-20 percent were told to use their own discretion,” Harris testified.

According to United Press’ reporting, Harris said his briefing officer at El Toro Marine Base had told him prior to shipping out to Korea that the old code, whereby a prisoner only provided name, rank and serial number, “is out.”

The story that the airmen had been tortured into false confessions remains the primary U.S. government narrative about the captured flyers’ confessions. It has been repeated so many times, it is considered established fact. It was buttressed by the tales of torture told by some of the airmen when they publicly retracted their confessions — retractions that were themselves coerced by threat of prosecution.

It seems that Wu (or whomever was writing his “memoir” in Wu’s name) decided not to delve too deeply into that issue in the “false alarm” essay. To the degree that the essay did take up the subject, it was wrong on the facts.

Confusion Over Timing of the Soviet “False Alarm” Memo

This particular point is a bit wonky, or “in the weeds,” but is still important. Wu stated that after the ISC committee left China, and ISC committee member, Dr. Nikolay Zhukov-Verezhnikov, returned to the USSR, “a telegram came [to the Chinese government] from the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party [CC-CPSU] saying that bacteriological warfare was a false alarm.” The Chinese leadership then “ordered a retraction” of its BW propaganda, and subsequently “China did not raise the matter again….” (Leitenberg, 2016, p. 72, bracketed material added)

Milton Leitenberg rightly noticed that Wu misquoted the CC-CPSU memo about there being a “false alarm,” and said the memo referenced “‘false’ and ‘fictitious’ information” (Leitenberg, 2016, p. 21).

Wu’s claim about the Soviet telegram, indicating the BW accusations constituted a “false alarm,” appears to be a reference to a purported CC-CPSU telegram, dated 2 May 1953, to Mao Zedong, which was translated and published by Kathryn Weathersby in 1998 (Document #8). This Soviet document stated, “The spread in the press of information about the use by the Americans of bacteriological weapons in Korea was based on false information. The accusations against the Americans were fictitious” (Weathersby, 1998, p. 183).

Such a telegram may indeed have been sent, as this claim was part of Beria’s campaign to destroy his rivals as he jockeyed for power in the weeks after Stalin’s death, using accusations of falsifying the BW record to impugn his enemies. This aspect of the entire affair is covered in my article, “Debunking the Debunkers,” Part One, “Prelude to a Frame-Up.”

Did Wu remember this telegram, or was he helped in remembering it? If Wu Zhili really wrote his “memoir” essay in September 1997, it would have been four months before the Japanese newspaper, Sankei Shimbun, published (in January 1998) what they claimed was the Soviet telegram text, along with eleven other documents said to have been found in the old Soviet archives. Did Wu know about the discovery of these documents? Did Leitenberg, who as we have seen above was active at the time in trying to ferret out Chinese “participants” in a purported BW “hoax,” show Wu the Soviet documents? In truth, very little is known about why Wu chose to write his “memoir” when he did (if he did), or why it was put away for years, only to surface much later.

If Wu really was referring to the May 1953 telegram in the Weatherby/Leitenberg collection, then his dating for it is not tenable. Wu stated the Soviet telegram about the “false alarm” came soon after the ISC had finished its work (September 1952), and after ISC member Zhukov-Verezhnikov had returned to the USSR (which was in October or November 1952). This means there is a seven to eight month gap between when Zhukov-Verezhnikov left China and the appearance of the CC-CPSU “false alarm” telegram. Why bother to even link the two? The entire assertion demonstrates once again Wu’s (or the Wu forger’s) laziness and/or nonchalance with dates and facts. If Wu was telescoping events in time that were months apart, what does that say for the accuracy of his entire narrative?