Further Thoughts on Alleged Presence of Biological Agents in WW2 Japanese Balloon Barrage

When isolated examples of documentary evidence contrast with a much larger body of historical evidence, and/or the historical record itself is incomplete, what's a reader — or a researcher — to do?

A short while ago, I published a rather long article that described revelations from certain declassified FBI reports which showed a portion of Japan’s balloon attacks over North America in the last year of World War 2 involved use of anthrax, and possibly bubonic plague.

This post serves as an appendix, if you will, to the original Japanese balloon article. I suppose what I’m doing in this post is thinking out loud. Ordinarily I would leave my research process and reflections to myself, tucked away in the rag-and-bone shop of my analytical self. But because the findings of my investigations are so heterodox, it seems to me that it would be helpful for my readers to further know how I came to make the conclusions I do based on the evidence I have seen.

I think it’s worth referencing a separate article I published recently on how the U.S. biological warfare program took up Japan’s idea of using high-altitude balloons as a biological weapons delivery system (code name “Flying Cloud”). The fact the U.S. contemplated this only after the experience with the Fu-Go balloons represents circumstantial evidence that the Japanese balloons had used biological weapons (BW). The U.S., upon this surmise, utilized Fu-Go as both inspiration and model. Indeed, the linked article above documents instances where such modeling was discussed.

But the temporal creation of the U.S. balloon bomb in relation to the Fu-Go attacks only rises to even circumstantial evidence regarding Fu-Go’s payloads when it is considered along with a number of other data points. These other data sources inform our understanding of the sequence of events that led to the secret Flying Cloud project. Without the totality of the available BW evidence in regards to Japan’s balloon barrage, the temporal contiguity of the U.S. balloon program would otherwise appear as a random, if intriguing, fact.

Reconstructing an incomplete historical record

Historical narrative reconstruction is not solely the task of historians of past or current news events. It is also the task of other occupations, not least, for instance, of those who seek the reconstruction of the history of the earth (geology), or the cosmos itself (cosmology). We also have the disciplines of anthropology, archaeology, and paleontology as further examples of reconstructive endeavors.

As one author put it, writing about Heinrich Schliemann’s 1870s archaeological discovery of the city of Troy, site of Homer’s Iliad, “It was Schliemann who recognised the cardinal importance of fragmentary evidence, who, when others attended only to statues and inscriptions as signifiers, dutifully preserved and interpreted apparently insignificant fragments and what he termed 'excrescences'.”

On another scale entirely, there is the project of the reconstruction of the important psychic events in a person’s life, which is the task of psychoanalysis or other related psychological and therapeutic endeavors. The essay that mentions Schliemann, quoted above, also describes Freud’s enthusiasm about developing methods of reconstructing a person’s life and its psychic development. Freud saw his project as having parallels with the field of archaeology: the problem of disjointed layers, the incompleteness of the given artifactual record, the problem of interpreting existing evidence, and the fact that so much remains hidden. Having spent over two decades as a clinical psychologist, I know something about these problems.

Noteworthy, too, is how the problem of historical methodology with respect to the fossil record and the history of life on earth was a central theme of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (see Chapter 9). Darwin addressed the problem by analyzing the reasons for the incompleteness of the fossil record, rather than simply making assumptions based on gaps.

The primary problem with determining the true history of the biological war program, whether that of the U.S. or of other countries (like Japan), is the fragmentary nature of the evidence we have available. The evidence is sketchy or discontinuous for many reasons. For instance, much evidence remains classified. Additionally, there is the fact that evidence has been destroyed, withheld, or falsified, or has been distorted by the extreme levels of secrecy and compartmentalization under which these programs operate.

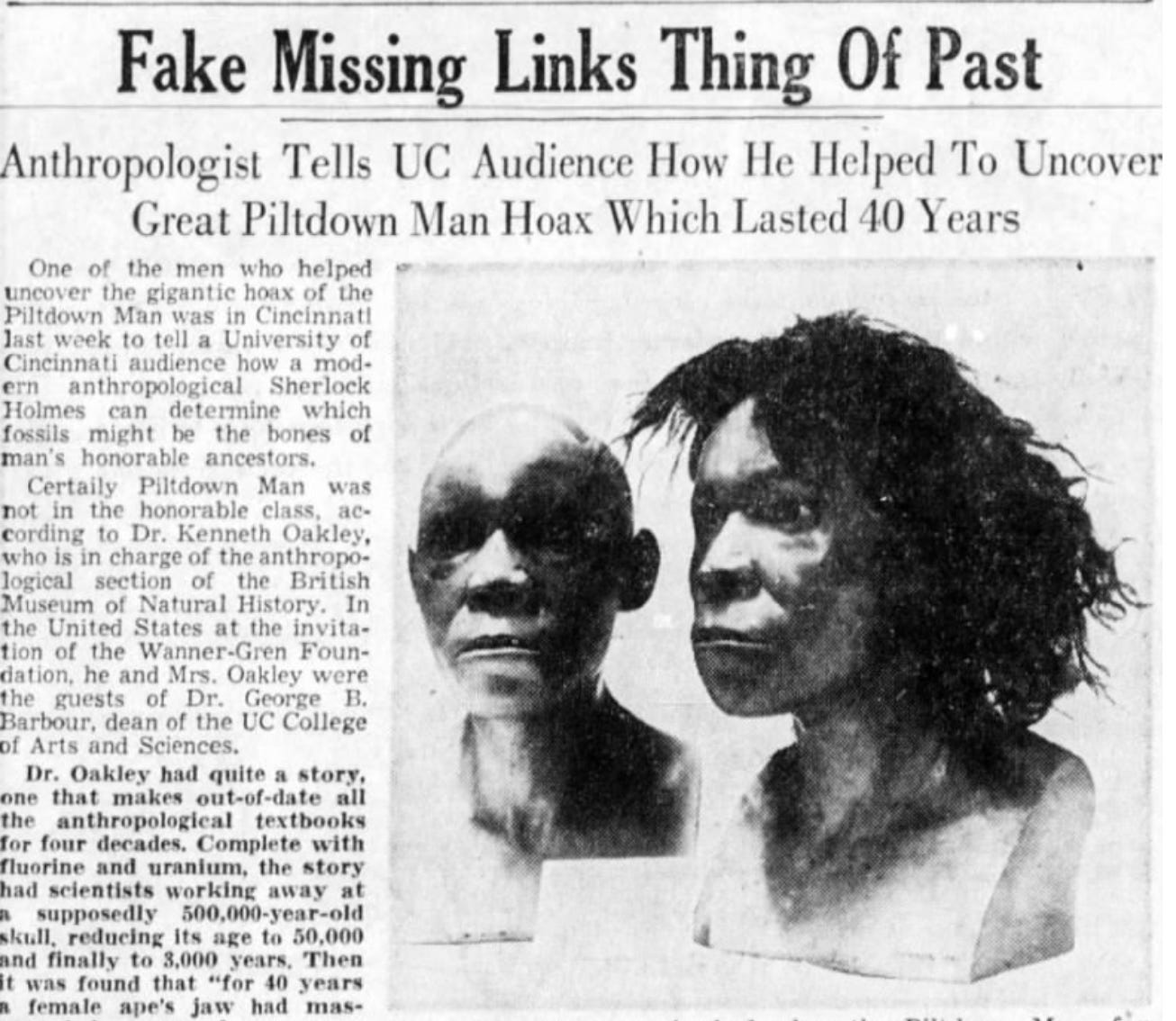

Leaning upon the analogies already given, the task of interpreting the extant materials on the biological war program is somewhat similar to reconstructing the fossil record, which is full of empty spaces and oddities, including, unfortunately, deliberate hoaxes or falsifications of the record, such as occurred in the infamous Piltdown Man case.

As I said, there also is the psychological example of dealing with the difficulties of reconstructing the relevant sections of a person’s life, which is already broken up into disparate episodes by psychological repression, misunderstandings, fear of others’ judgment, previous partial attempts at remembering, and mere forgetfulness.

In these situations, we must correlate, or colligate, all the knowledge we have and see via induction what connections between the available data points make sense. The English historian of science, William Whewell, called this the “consilience of inductions.”

These connections are then evaluated by their internal consistency, their falsifiability, by their ability to predict missing portions of the data (their heuristics), as well as by other unexplored or new connections as they are discovered or revealed.

The evidence surrounding the Japanese balloons is certainly fragmentary. There is the fact that thousands of launched balloons never were recovered, the vast majority of them in fact. Then there is the frustrating circumstance that the documentation for the Fu-Go project was destroyed in Japan. The analysis of the balloons and their payloads was additionally subject to secrecy classification in the U.S. and Canada. The suppression of balloon landings in New Mexico, even among individuals or agencies that otherwise held various levels of security clearance, is testimony to that. Contemporaneous reporting on the balloons was also censored in the press. It’s amazing we know what we do.

Due to the ongoing classification (or censorship) of certain elements of the FBI balloon memos, not all the individuals involved in the memos are known to us. But we do know they had responsible positions. Two of the primary FBI informants were themselves responsible for military investigations of the Japanese balloon sightings in certain regions of the U.S. and Canada.

The primary document for my Fu-Go article was also its potential Achilles heel, in that the evidence is partly censored as to origin, and remains second-hand in nature. I’m speaking here of the July 6, 1945 FBI memorandum to the Chief of the FBI’s Domestic Intelligence Division, Daniel M. Ladd. The memo described a briefing the Special Agent in Charge (SAC) at the Norfolk FBI office received from a military official at Langley Air Force Base. This military official was described as someone who was “until recently… assigned to handling investigations concerning the landing of Japanese balloons in the states of North and South Dakota, and Nebraska.”

The FBI memo quotes the Norfolk SAC: “I was interested to learn that recently several Japanese balloons were found in that territory [the Dakotas and Nebraska] which were determined to have been carrying bacteria. The bacteria consisting of Anthrax, are placed in the hydrogen.”

One expert on the Japanese Fu-Go balloons I consulted, who declined to be identified, felt this was probably a “false report”. I considered this seriously. Indeed, the vast bulk of the literature on the subject repeatedly states that despite fears of possible bioweapons payloads on these balloons, none were ever found. This is not just the conclusion of historians, but of putative military authorities who were reporting on the balloons in contemporaneous top secret reports.

A notable example of the latter can be found in an important October 1945 report by George W. Merck, the head of the U.S. government’s World War II biological weapons agency, the War Research Service. The secret report was addressed to the Secretary of War in or around October 1945:

“From the begining of the recent Japanese balloon attack, all equipment salvaged from the balloons was examined for the possible presence of b.w. agents. These investigations were performed at Camp Detrick, and happily yielded negative results.” (PDF pg. 30)

Faced with the contradiction between the clear statements about the presence of BW in the Fu-Go balloons made in the Memo to Ladd, and the categorical conclusions of varied authorities, I did what a researcher should do when faced with such a dilemma. I dug deeper.

I asked the National Archives (NA) to further declassify a 1950 memo from FBI Director Hoover’s office that also suggested that there was bubonic plague on some of the balloons that had landed in New Mexico. The NA was very obliging. The new unreacted material revealed there had been similar allegations of balloon-delivered plague from balloon landings in northern Alberta, Canada. Moreover, the Canadian authority had passed on his suspicions to an American colleague (about which more below).

The newly declassified sections of the Hoover memo provided an intriguing case of corroborative evidence about the balloons containing BW, but the evidence was still circumstantial, or rather inferential, i.e., not direct. This is not an unusual circumstance in determining biological weapons attack. Detection of BW attack remains to this day, despite modern technology, a daunting and incomplete effort, as this December 2000 paper in Analytical Chemistry explained:

BW agents need to be detected and identified at extremely low concentrations in complex, changing backgrounds in near real time with little power consumption and no reagents. Clearly, existing systems do not meet the needs of the military or civilian sectors for the purpose of “detect to warn”. They suffer from relatively poor sensitivity, occasional false positives, and lengthy response times.

In any case, I have found to date no follow-up memos on the bubonic plague cases linking them definitively to the Japanese balloons. Nor have I found any other documents suggesting the balloons carried biological pathogens.

On the other hand, I have also not discovered any memo correcting previous incorrect assessments regarding the presence of BW in the balloons. You would think “false reports” — especially such reports forwarded to high FBI officials or directorates of other U.S. intelligence agencies — would generate rectifying material in the form of follow-up messages or memoranda. But none exist in the available record.

It is my opinion that too many historians and reporters ignore discordant evidence when it opposes that of institutional authorities. Of course, that puts me in the company of a lot of unsavory people who peddle nonsense and the kind of embarrassing analysis that fills denunciatory reviews of “conspiracy theories.” But it also puts me in some good company as well.

It’s worth setting out my thinking on the record on the Japanese balloon story, as it relates to other instances when the official record has been proven to be mistaken. The related salient example is the evidence relating to the U.S. use of biological weapons in the Korean War.

Unusual phenomena

In regards to the 1950 memo, the individual who reported the strange plague evidence in New Mexico was a highly respected scholar, Lincoln LaPaz, not known for making fanciful statements. His work for the government on the Japanese balloons is not generally known. He was in contact with others in the military or intelligence community, hence his forwarding to J. Edgar Hoover a report from a Canadian official involved in investigating the Japanese balloons.

The Canadian official who suspected plague in northern Alberta was an authoritative source himself. While his identity has been withheld, in my original article on the balloons, I speculated that this was Lt.-Cmdr. E.L. Borradaile, Commanding Officer of Canada’s Inter-Service Bomb Disposal Centre.

For his part, Borradaile, or whomever the Canadian communicant with LaPaz was, seemed confident that the unusual plague outbreaks in northern and western Alberta followed the tracks of known Japanese balloon sightings. This is still circumstantial evidence. But there were some other aspects to this plague story that are strange.

Why was it that LaPaz, who certainly was in a position to know, reported that a number of Japanese balloons came down in New Mexico, when not one military or intelligence report, or authoritative history that I’ve read has indicated that even one such balloon was ever spotted in New Mexico? That evidence must have been known, yet was withheld from (or by!) government investigators writing reports on Fu-Go.

Why do the official lists of balloon sightings in Alberta only mention two or three balloon sightings in the northern part of the province, when a photo of Borradaile describing the balloon sightings in Alberta at the time show that there were obviously more than just a few such balloons in the area?

Is it possible to bury sensitive information in government hands such that it never sees the light of day? Yes. It is. In the case of the Japanese balloons, it is of course highly suspicious that the destruction of documents at the end of the war was, according to an account I quoted (p. 176) in my original balloon article, the number one priority of Japanese military authorities.

Whatever uncertainties I may have about the truth of the Japanese balloon story coming from the FBI documents are reduced by my knowledge of other areas where evidence has been ignored or covered-up in government documents, journalistic accounts, or well-regarded histories.

In my original balloons article, I mentioned the activities of Japan’s biowarfare division, Unit 731. If you read the histories of postwar biological warfare development, or Department of Defense documents from the period, such as those from the U.S. Army Chemical Corps, you never hear a peep about Unit 731, or of the U.S. amnesty of the 731 researchers, or how the Army and CIA researchers studied materials handed to them from Japan’s secret biowarfare unit. The truth about all that wasn’t revealed until 35 years after the end of WW2, when John W. Powell released his landmark research in the pages of The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists.

Many materials never make it to the mainstream media. Using declassified documents from the NCIS investigation into the death of Guantanamo detainee Abdul Rahman Al Amri, who died in May 2007 at Camp 5 at Guantanamo’s Camp Delta, in an investigation some years back I showed that he was found hanged in his Gitmo cell with his hands tied “snugly” behind his back. His bedsheets were supposedly threaded via tiny holes in a grate nine feet off the floor, a circumstance that led to the destruction of the air grate by Guantanamo authorities. (The grating was also too high and the holes too small — the diameter of a #2 pencil — for the constantly surveilled prisoner to complete the hanging mechanism alleged. The sheets ripped to create the ligature for his hanging were supposed to be tear-proof.)

Even more, the circumstances of Al Amri’s whereabouts the morning of his death were falsified, and the computer records regarding prison operations the day of his death were tampered with. But none of this ever made one news account, teaching me thereby a number of things. One is the insular incuriosity of the mainstream press and its blogosphere epigones. Additionally, I had to reflect upon the powerful effect of government suppression, including deliberate (and sometimes accidental) destruction of evidence. How much the latter is a factor is important in assessing historical evidence.

The story about Japan’s balloon barrage has changed over the years. For over five decades, U.S. researchers accepted as good coin the claim of Japanese scientists that the balloons were never meant to carry biological agents. But, as discussed in my original article on Fu-Go, a memoir by a Japanese scientist proved that in fact the originators of the balloon barrage at the Japanese military’s Noborito Research Institute had in fact meant to fill the balloons with rinderpest (“cattle plague”) virus and send them over North America. The story of “never intending a biological payload” was changed to one of, “yes, they were intending such a weapon, but called it off at the last minute.”

The Unit 731 scientists also told U.S. investigators for some time that they never tested their biological weapons on any human subjects. Later it was revealed that they had, and killed a minimum of 3,000 prisoners in such fashion over a period of years. Their prisoner “subjects,” which they referred to as “logs,” died horribly grisly deaths as a result. In fact, Japan’s biological research scientists and military authorities from that period were proven liars. Why should we believe we now have the full story about the use of the balloons?

On the other hand, it would be folly to dismiss the vast bulk of materials, including lab reports I’ve seen, that say there were no biological payloads. So I think I need to say how I think it came about that bioweapons were used at all.

A Hypothesis

Accepting the story that the original rinderpest payload was cancelled, and taking into account the fact that Noborito and Unit 731 shared personnel, I think what happened was that the rinderpest agent was cancelled because it violated a prime criterion of biological weaponry. The relevant criteria here is that a biological weapon attack should not be immediately identifiable as to source. It optimally should not even be immediately determinable that a disease outbreak is due to any attack. To do otherwise is to invite counter-attack.

As Matthew Sprinkle said in a review of Gregory Koblentz’s 2011 book, Living Weapons: Biological Warfare and International Security:

… biological weapons necessarily rely on surprise to achieve their devastating effects, because once the biological threat agent and the location where the threat agent will have its effects, in at least some cases [is known] the defender can seek to establish defenses, such as medical treatments or cures, vaccines to limit susceptibility, and area quarantines or similar measures to prevent the threat agent’s spread. In cases of genuinely novel or unknown biological agents, or agents that spread with great rapidity, of course, these measures are far from assured to defend against the attack. But in either case, surprise attack is a core element of the success of the attacker.

Along similar lines, a 2004 “historical review” of “Biological warfare and bioterrorism” noted:

Biological weapons are unique in their invisibility and their delayed effects. These factors allow those who use them to inculcate fear and cause confusion among their victims and to escape undetected. A biowarfare attack would not only cause sickness and death in a large number of victims but would also aim to create fear, panic, and paralyzing uncertainty. Its goal is disruption of social and economic activity, the breakdown of government authority, and the impairment of military responses.

Rinderpest was unknown in the United States during this period. An outbreak of rinderpest would be a red flag to biological warfare intelligence officers. A central issue is what were the known or surmised intentions of Japan’s balloon barrage effort.

On one hand, it seems, the Japanese wanted to get revenge for the U.S. attacks on Japan’s home islands. They wished to stir panic and chaos inside the United States. But military staff did not wish to invite BW counter-attack upon Japan. Military uses of biological warfare generally call for either incapacitating or killing one’s enemy.

It made sense then, for any nation contemplating use of biological weapons, that any biological agent used should be difficult to assess regarding point of origin. Is a discovered outbreak of natural origin? Is it a covert attack? Is it zoonotic or contagious in humans? Does it come from existing biological lab experiments? All one has to do is consider the ongoing controversies over SARS-Cov-2 to appreciate the complexities involved.

The difficulty in assessing BW attack is made even more apparent when the potential biological agents used are already endemic or otherwise known to exist in the targeted area. Anthrax is endemic in the U.S. midwest. Plague was and is endemic in the American West, also in the U.S. border regions of Canada. Again, rinderpest was non-existent there.

A totally different problem for those considering a Japanese balloon BW attack is that the Japanese could not determine exactly where their balloons would land or release their payloads. The balloons were engineered to maintain certain altitudes, but otherwise were at the mercy of the prevailing, and sometimes shifting, winds.

While anthrax and plague were endemic, they did not occur in every geological area. The examples given in the FBI reports, at least so far as plague is discussed, explain that plague appeared in areas of New Mexico (elevation) and Alberta (geographical region) where it was otherwise unknown or had no history. This constitutes not just circumstantial evidence, but ecological evidence. The presence of the balloons, a weapon that was already feared to carry a biological payload, close by the disease outbreak areas made a correlation between the balloon landings and the appearance of plague a plausible hypothesis.

At some point, and probably under the influence of Shiro Ishii’s Unit 731, which had plenty of BW experience, with rinderpest out of the picture, a decision was made to try using anthrax and bubonic plague. The decision came too late in the Fu-Go balloon campaign to make much difference in outcomes. But the exercise in biological warfare was made, most likely with the hope, still, in Spring 1945 that there was more time for future balloon campaigns in the war come late autumn when the prevailing high-altitude winds would turn favorable again.

Alas for the leaders of Unit 731 and Noborito, August 1945 brought the double whammy of the atomic bombings and the Soviet rout of the Kwangtung Army in Manchuria, and the end of the war before the summer was out.