Secret History: U.S. Flyers’ Confessions Regarding Use of Biological Weapons in the Korean War

These POW depositions, suppressed in the U.S., created the biggest controversy of the Korean War. They provide a unique, extraordinary narrative of how the U.S. germ warfare campaign unfolded.

On the morning of the 5th of June, 1952, Colonel Clark, logistics officer of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, called me into his office where he was alone and asked about my progress in becoming familiar with the ordnance job….

[Colonel Clark] paused and asked: “What do you think of the use of the germ bomb?” I said: “Sir, it’s not only against my own principles but it would also certainly leave a black mark against the Marine Corps’ reputation.” The colonel said he didn’t approve of its use either, nor did anyone else in the Wing but we were ordered to do so by higher authority and there was nothing to do but obey our commands.

— from deposition of USMC Major Roy H. Bley, January 21, 1953

I do not say the following in defense of anyone, myself included, I merely report as an absolutely direct observation that every officer when first informed that the United States is using bacteriological warfare in Korea is both shocked and ashamed….

Tactically, this type of weapon is totally unwarranted — it is not even a Marine Corps weapon — morally it is damnation itself; administratively and logistically as planned for use, it is hopeless; and from the point of view of self respect and loyalty, it is shameful.

— from deposition of USMC Colonel Frank H. Schwable, December 6, 1952

Nobody comes out of the biological warfare program smelling like a rose.

— unnamed military official to U.S. Air Force historian Dorothy Miller, quoted in History of Air Force Participation in the Biological Warfare Program, 1951–1954 (p. 66)

Preface

Since first publishing this article at Medium.com, I subsequently — and surprisingly — discovered that the flyers discussed in this article apparently were all given instructions prior to the onset of their Korean service that if captured, they were to tell their captors whatever they knew. They were not to be bound to silence, or the mere rendering of name, rank, date of birth and serial number.

I found this surprising fact in an examination of the Marine Corps’ 1954 Board of Inquiry into the alleged collaboration of Colonel Frank Schwable with his Chinese captors. Schwable is discussed at length further on in this article.

Needless to say, the revelation that captured flyers had carte blanche to “tell them anything they want to know” (as captured flyer Walker Mahurin explained it in his autobiography) throws a definite wrinkle into the interpretation of what occurred when the flyers’ confessions were made, and how they were interpreted in the West afterward. The full story about this aspect of the flyers’ confessions and the germ warfare story can be read here.

The article which follows has been very lightly edited, and includes some new information not published in the original Medium story.

The First Confessions

In May 1952, China state radio broadcast statements from two United States Air Force flyers, Lt. Kenneth Enoch and First Lt. John Quinn, detailing their participation in biological or “germ warfare” attacks on North Korea, the first broadcast by U.S. captured prisoners admitting complicity in germ warfare attacks against China and North Korea. More such broadcasts were to come, along with written depositions to Peoples Republic of China officals.

The broadcast by Enoch and Quinn came some three weeks after a press conference given by a delegation from the International Association of Democratic Jurists, who, having toured over a dozen purported sites of biological weapons (BW) attack in North Korea in March, also claimed evidence of U.S. germ warfare.

For decades the claims by North Korea and China of U.S. use of biological weapons have been dismissed precisely because the evidence came from Communist or supposed Communist-friendly sources. Existing evidence in U.S. archives was considered suggestive, but circumstantial. A military historian who examined the issue claimed that according to the secret record to which he was privy, the U.S. was incapable of waging biological warfare during the early 1950s.

Meanwhile, in 1998, two Cold War scholars, Kathryn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg, associated with the Woodrow Wilson Center, published documents, allegedly from former Soviet archives, detailing an elaborate hoax to manufacture false evidence of U.S. biological weapons attack.

It wasn’t until September 2020 that evidence from U.S. archives was published that appears to definitively document U.S. BW attack. The evidence consists of declassified CIA communications intelligence reports, dozens of which quote U.S. Army intercepts of North Korean and Chinese military units describing “bacterial” attacks, including by use of insect vectors, in a style similar to that of Japan’s Unit 731 during World War II.

The initial public claims of a massive air campaign using biological weapons against Communist forces in the Korean War came in a February 22, 1952 statement by North Korea’s foreign minister. The full text of that statement was suppressed in the United States, as were the complete statements by the two fliers, Enoch and Quinn, and twenty-one more “confessions” released by the People’s Republic of China over the next year and a half. (Two further “confessions” were published in the September 1952 report of the International Scientific Committee.)

The selections from the flyers’ confessions that follow represent only the second publication in a Western media setting of primary materials describing the biological warfare campaign, including the aims of the program, who approved it, the evolution of the air war, where the specialized ordnance came from, training of special unit handlers, etc. (The version of this article published at Medium.com was the first such publication.)

The selections of the depositions below are from the statements given by U.S. Marine Corps officers Frank Schwable and Roy Bley, and U.S. Air Force officers Walker Mahurin and Andrew Evans, Jr. Only Colonel Schwable’s deposition has previously been available to the public. Substantive portions of the statements from the other three officers are published here for the first time. (To the degree any of the depositions fall under U.S copyright law, and I don’t believe they do, the selections herein constitute fair use of a much larger collection of material.)

Looking for the Missing History of the Flyers’ Confessions

It was the profound unavailability of the flyers’ depositions to their captors on the use of BW that first led me to pursue the text of these statements. In November 1953, the “Chinese People’s Committee for World Peace” published a collection of nineteen of these BW confessions in book format. According to World Cat, there are only three such copies left available in the United States, one of which is in the Library of Congress. The other copies were presumably confiscated and destroyed by the U.S. Postal Service and/or the Customs Department in a program to interdict Communist propaganda that was in effect from 1951 to 1965.

The shock value of the confessions of a number of U.S. POWs, some of them high-ranking U.S. military officers, led the U.S. to not only deny outright the claims in the flyers’ statements, but also fed a propaganda campaign about “brainwashing” of U.S. POWs that was propounded for years by U.S. military and intelligence agencies, and which was duly reported in fantastical form by Western journalists. In 1978, having gained access to numerous CIA documents on its MKULTRA program, John Marks was able to finally expose CIA machinations about supposed “brainwashing.”

The controversy surrounding the captured flyers’ statements are noted in many histories of the Korean War, but none of these histories includes a comprehensive description or analysis of the flyers’ statements. A few allegations are typically singled out and then supposedly disproved by statements from U.S. government authorities, or by reference to this or that document, or rebuttals by seemingly authoritative academic sources. But the detailed claims made by the flyers are never themselves really addressed.

In total, the depositions of the flyers’ statements, for which we have now 25 full “confessions” in print (see here, here, and here — the latter two being rough scans from original PRC publications), are only a subset of what must be more such confessions, which remain unreleased or unavailable for some reason. In February 2021, a digital book was published that contained transcriptions of all the flyer confessions (though I have not checked to see how their accuracy compares with the originals).

There also are a few videos online that in part include portions of Enoch and Quinn’s statements. See this video, with partial statements in English beginning at 10:29 and 11:50 time marks. Of much importance as well is Tim Tate’s 2012 documentary for Al Jazeera’s People and Power, “Dirty Little Secrets,” which has snippets of both confessions and retractions by U.S. flyers culled from Chinese and U.S. propaganda films.

According to Dr. Louis J. West, a CIA psychiatrist who worked with Air Force prisoners after their return from captivity (and also worked on MKULTRA and military projects, helping establish the modern CIA model for psychologically coercive interrogations), there were a total 83 USAF prisoners of war interrogated about involvement in BW attacks. Of these, 36 provided “some confession” to their PRC captors, and 23 of the 36 had their confessions subsequently published for “propaganda” purposes. (Two non-Air Force POWs who had published “confessions” were from the Marine Corps, and not included in West’s figures.) See “Methods of Forceful Indoctrination: Observations and Interviews,” Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, July 1957, p. 274.)

In the selections from the flyers’ statements reproduced below, I have chosen those from higher-ranking officers, who were in a position to know the details about the planning and operations of the overall biological war effort. They include a former Assistant Executive to the Secretary of the Air Force, the former assistant to the Executive to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, a Marine Corps ordnance officer, and the highest ranking of the POW confessors, the Chief of Staff of the First Marine Aircraft Wing.

The confessions have been portrayed in the past as the product of torture, as full of lies and false or fantastical statements. A full analysis of the flyers’ “depositions” awaits a future historian.

From my examination, the “confessions” as a whole present a rational and believable narrative, one unlikely to have been concocted by foreign interrogators. Many of the individuals and organizations cited can be corroborated by external sources. It is expected that some prisoners’ level of resistance to their captors would result in occasional deliberate falsifications within the overall confession, as well as some deliberate omissions of sensitive material. I doubt, for instance, that the BW weapons ever had the code word “Suprop,” as Col. Schwable testified. Why? Because I can find no reference to the term anywhere else. It may still be true, but it seems not. Much else in his deposition rings true however. Perhaps by withholding the real codename, Schwable was able to maintain some dignity or belief that he was still resisting.

The confessions overall present the reader with a complex admixture of compliance and resistance. They are the product of men under intense stress. Each of the prisoner confessions likely differs in the amount of such compliance or resistance, as each individual is motivated differently, and had variable reactions to stress, as Dr. West pointed out in his 1957 presentation to Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, which was attended by other MKULTRA scientists.

“There was no such thing as 100% compliance or 100% effective resistance,” West said. While the CIA-linked psychiatrist deemed all the flyers’ statements “false confessions,” his point about the complex motivations of men acting in an interrogation session in captivity holds. Even within the sample of confessions presented below, prisoners differed in the strength of their reaction to participation in the biological warfare campaign itself.

The statements often contain personal touches that could only have come from the individuals themselves, not from Chinese brainwashing villains. Take, for instance, Col. Schwable’s idiosyncratic complaint, quoted at the beginning of this article, that BW “is not even a Marine weapon.” This appears to be a spontaneous observation from the heart of a dedicated officer, not something a clever interrogator inserted for verisimilitude.

The sad truth is that even with more and more information being released to document the actuality of the U.S. biowarfare effort in Korea, there is precious little appetite among historians or the press to analyze this material, or to further pursue the historical truth surrounding the BW charges. This is despite the fact that the Korean War was never fully concluded, and the region remains a flash point for possible nuclear war.

For decades, it has been political orthodoxy that the Korean War POW BW confessions were nothing but lies, tortured nonsense without value or need for further examination. One thing seems certain, U.S. authorities did not want people to look at this material in any detail.

Confessions and Recantations: The Evidence For and Against

In December 1954, the United States forwarded to the United Nations eight statements from flyers who had earlier confessed to knowledge of or participation in the BW operations, along with statements from two captured Air Force prisoners who allegedly were interrogated by Chinese interrogators about BW but refused to confess. (See pgs. 46 to 81 in this document.) All 36 flyers who made some kind of confession were filmed making public retractions after their return to the United States.

A few statements from former prisoners were publicized upon returning to the United States. One such example was an interview with four repatriated Air Force officers in the September 18, 1953 edition of U.S. News and World Report (pp. 20-26). The article was titled, “BACK OF GERM-WAR HOAX—TORTURE / U.S. Officers’ Own Story of Forced ‘Confessions’” (all caps in original). This article will look more closely below at one of the major claims made in these interviews.

The recantations sent to the United Nations include those issued by Schwable, Mahurin, Bley, and Evans, the same POWs whose depositions I am publishing in part below. While all those who confessed to use of germ warfare are said to have recanted, these eight recantation statements seem to be the only ones available for examination (for now, anyway). Lt. Kenneth Enoch’s retraction can be seen in Tim Tate’s documentary mentioned above, at time stamp 37:27.

It is my contention that the factual material presented in the various depositions published by China can best be assessed by whatever corroborative material can be found in the public record. There is no way to go back in time and assess whether or not this or that POW was tortured or maltreated. For their part, both the PRC and the DPRK denied maltreatment of prisoners. When approximately 10 years ago documentarian and author Tim Tate interviewed former U.S. Air Force Lt. Kenneth Enoch about whether he was maltreated by his North Korean captors, he denied ill-treatment, while dismissing allegations that the Communists had tried to indoctrinate him. (See interview with Kenneth Enoch beginning at timestamp 38:50 in Tate’s film.)

While charges of torture or prisoner abuse carry important weight — and the U.S. has its own scandals in relation to that — looking back almost 70 years later at historical documents, it seems wrong to dismiss these statements describing the U.S. BW campaign based on how the flyers were or were not treated. We must rely on the evidence regarding biological warfare that is before us, and whether or not it can be corroborated.

An example of such corroboration concerns the depositions given by Colonels Schwable, Mahurin and Evans, all of which state that the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave the order to proceed with the germ warfare campaign in October 1951. While no written order to that effect has ever been released, it is noteworthy that on September 21, 1951, a top secret memorandum from the Joint Advanced Study Committee to the Joint Chiefs of Staff called for the acquisition of “a strong offensive BW capability without delay,” and use of such weapons “without regard for precedent as to their use.” The memo called for the establishment of “a BW indoctrination course” for military personnel, and the use of BW “whenever it is militarily advantageous.”

Even more, according to historians Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagerman, who first described the September 21 memo, “The memorandum endorsed the covert potential of bacteriological warfare, and made specific recommendations on tactical use that were conspicuous for their pertinence to the Korean War” (pg. 83 at link, also pg. 201).

Examples of such recommendations included use of BW “when enemy troops are in assembly and concentration areas or on the move to the front….” (Ibid.) As we shall see in the statements reproduced below, this comports with the description of BW tactics described by the flyers in their depositions.

The JCS formally approved the recommendations in February 1952, but there’s nothing to preclude the fact they may have acted on those recommendations earlier.

Meanwhile, it was clear to the U.S.’s international partners in biological warfare research, the British and the Canadians, that the U.S. was serious about using bacteriological weapons in Korea. In secret, classified meetings, they discussed this among themselves. As an example, in a secret memo dated December 27, J.C. Clunie, Canada’s Defence Research Board Senior Staff Officer for Special Weapons, wrote to the Chief Superintendent at the biological and chemical weapons test site in Suffield, Alberta, “The USAF is giving serious consideration to the probable use of BW and CW Special Weapons.”

I have also explored elsewhere important organizational changes inside the U.S. Chemical Corps’ biological warfare program around October 1951 that seem related to the rush then underway to create biological weapons of “immediate benefit to operational effectiveness.”

For the purposes of this article, it’s important to note that the returning prisoners who renounced their statements about germ warfare did so under the tremendous pressure of threatened prosecution or court-martial. They underwent repeated debriefings and examinations by military and CIA officials, and affiliated medical and psychiatric personnel. According to historians June Chang and Jon Halliday, the FBI followed them for years, part of “a vast surveillance campaign on returned POWs” (p. 371 at link).

In his autobiography, Honest John, Walker Mahurin recounted his experience after he was repatriated after the war, commenting on the social ostracization he experienced from people in the military-intelligence-business circles that he frequented. He wrote that he faced “a critical government at home and possibly a court-martial in the near future…. the specter of a court-martial seemed to be ever-present” (pp. 375–376). If Mahurin, who was very well-connected, felt this way, what did lesser officers and flyers feel? What kinds of pressure were they placed under?

Mahurin’s written retraction of the BW charges was submitted three days after leaving Korea by ship back to the United States to “a psychological warfare officer on board — a man who was to take depositions from all of us who had made germ-warfare confessions” (p. 348).

Mahurin described how, after undergoing a horrific (and suspicious) auto accident soon after his return to the U.S. mainland, he underwent two weeks of interrogation by the Air Force Office of Special Interrogations. Among other things, Mahurin was asked to inform on other prisoners.

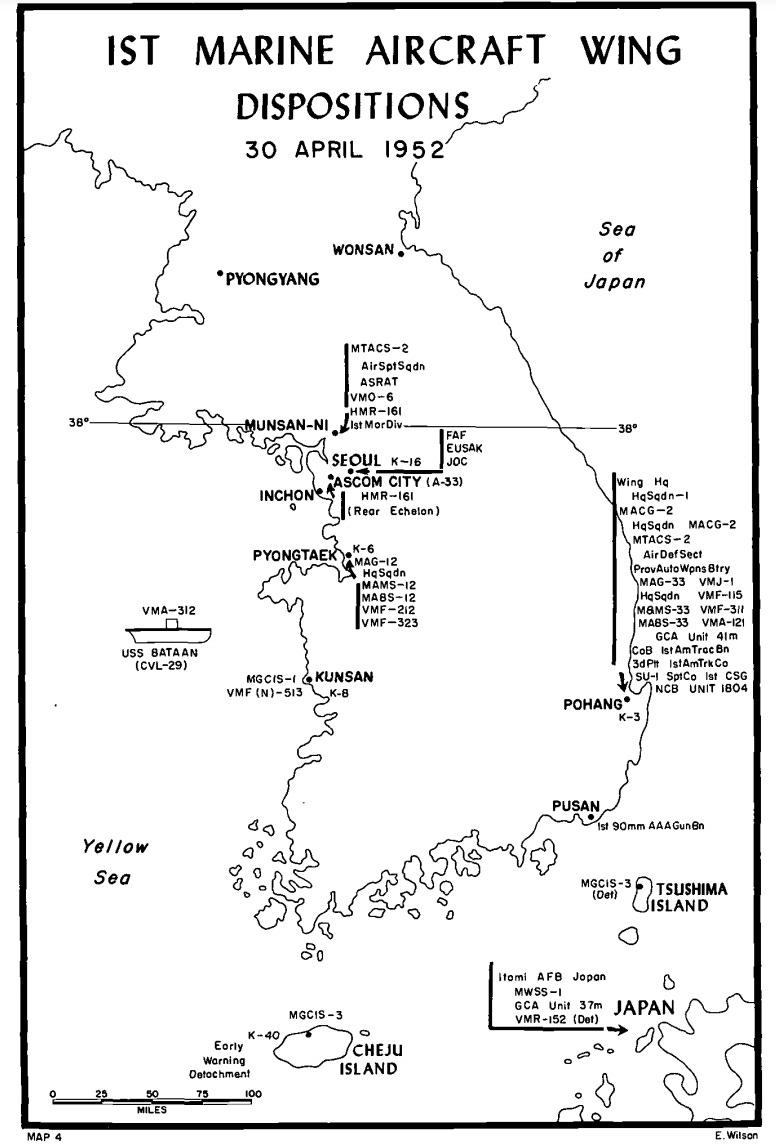

In his recantation, Schwable described his deposition for the Chinese interrogators as “this false, fraudulent, and in places absurd confession.” (link, p. 54) But according to his sympathetic account of Schwable’s incarceration and later investigation by U.S. authorities, Raymond Lech noted that Schwable “revealed quite a bit of classified information” (p. 157–158). In fact, his depositions “reeked with” classified material, including the names of his commanding officers; the bases and geographic locations of Marine Aircraft Groups 12 and 33; provision of sensitive order of battle information; descriptions of the form used to fill out mission reports for Fifth Air Force; classified locations of air bases, and more.

Selection from Flyers’ Statements: Colonel Frank Schwable, USMC

Col. Frank Schwable, as Chief of Staff for the First Marine Air Wing, was the highest ranking Marine Corps officer captured during the Korean War. He was shot down and captured, along with his co-pilot Major Roy Bley, on July 8, 1952. Five months later, allegedly held in solitary confinement and subjected to threats and forced standing, Schwable signed a detailed confession to his role in the germ warfare campaign, and described how it was organized and approved by senior Pentagon officials.

Schwable’s position was quite senior. According to researcher-author, Raymond Lech, “The First Marine Wing was huge, consisting of thousands of men and hundreds of planes.” (Tortured into False Confession, p. 24) Four colonels reported to Schwable, including those responsible for intelligence (G-2), operations (G-3), and logistics (G-4). According to an official Marine Corps history of operations in Korea during the war, while Schwable’s deposition to his captors was “a most convincing lie,” Schwable’s confession nevertheless “was, unquestionably, damaging.”

After his return home, and despite his renouncing his confession as derived under undue stress, Schwable was brought up before an official Marine Corps Court of Inquiry.

Already repeatedly interrogated upon his return from captivity to U.S. custody, in September 1953 the Court of Inquiry had Schwable examined by Dr. William Overholser, professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, and superintendent of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for the mentally ill.

Unknown to Schwable, and likely to anyone in attendance, during World War II, Overholser had overseen the Office of Strategic Services’ research into developing a “truth serum.” His intelligence connections remained unknown for years, until John Marks published his landmark book, The Search for the Manchurian Candidate, based on hundreds of then-newly declassified CIA records. Some of Schwable’s own descriptions of his mental state, his “menticide,” appears shaped by discussions with government psychiatrists and/or psychologists.

One of the four officers on the Marine Corps Court of Inquiry was Major General Christian F. Schilt, commanding general for the First Marine Air Wing, until he left that position on April 12, 1952. Schwable mentions Schilt in his “confession” as involved in giving orders to his unit to participate in the germ warfare campaign (see excerpts below). To my knowledge, no one has ever mentioned the impropriety of including Schilt on Schwable’s Court of Inquiry.

From Col. Schwable’s deposition, dated December 19, 1952, published as three separate but related depositions, which along with the deposition by Major Roy Bley (see below) was printed in a “Supplement to ‘People’s China,’ March 16, 1953, pgs. 3–13, photostats of which can be found online:

The general plan for bacteriological warfare in Korea was directed by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff in October, 1951. In that month the Joint Chiefs of Staff sent a directive by hand to the Commanding General, Far East Command (at that time General Ridgway), directing the initiation of bacteriological warfare in Korea on an initially small, experimental stage but in expanding proportions.

This directive was passed to the Commanding General, Far East Air Force, General Weyland, in Tokyo. General Weyland then called into personal conference General Everest, Commanding General of the 5th Air Force in Korea, and also the Commander of the 19th Bomb Wing at Okinawa, which unit operates directly under FEAF….

The basic objective was at that time to test, under field conditions, the various elements of bacteriological warfare, and to possibly expand the field tests, at a later date, into an element of the regular combat operations, depending on the results obtained and the situation in Korea.

The effectiveness of the different diseases available was to be tested, especially for their spreading or epidemic qualities under various circumstances, and to test whether each disease caused a serious disruption to enemy operations and civilian routine or just minor inconveniences, or was contained completely, causing no difficulties. Various types of armament or containors [sic] were to be tried out under field conditions and various types of aircraft were to be used to test their suitability as bacteriological bomb vehicles.

Terrain types to be tested included high areas, seacoast areas, open spaces, areas enclosed by mountains, isolated areas, areas relatively adjacent to one another, large and small towns and cities, congested cities and those relatively spread out. Every possible type or combination of areas were to be tested.

These tests were to be extended over an unstated period of time but sufficient to cover all extremes of temperature found in Korea.

All possible methods of delivery were to be tested as well as tactics developed to include initially, night attack and then expanding into day attack by specialized squadrons. Various types of bombing were to be tried out, and various combinations of bombing, from single planes up to and including formations of planes, were to be tried out with bacteriological bombs used in conjunction with conventional bombs.

Enemy reactions were particularly to be tested or observed by any means available to ascertain what his counter-measures would be, what propaganda steps he would take, and to what extent his military operations would be affected by this type of warfare.

Security measures were to be thoroughly tested — both friendly and enemy. On the friendly side, all possible steps were to be taken to confine knowledge of the use of this weapon and to control information on the subject. On the enemy side, every possible means was to be used to deceive the enemy and prevent his actual proof that the weapon was being used.

Finally, if the situation warranted, while continuing the experimental phase of bacteriological warfare according to the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive, it might be expanded to become a part of the military or tactical effort in Korea…..

The B-29s from Okinawa began using bacteriological bombs in November, 1951, covering targets all over North Korea in what might be called random bombing. One night the target might be in North east [sic] Korea and the next night in North west [sic] Korea. Their bacteriological bomb operations were conducted in combination with normal night armed reconnaissance as a measure of economy and security.

Early in January 1952, General Schilt, then Commanding General of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, was called to 5th Air Force Headquarters in Seoul, where General Everest told him of the directive issued by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and ordered him to have VMF-513 — Marine Night Fighter Squadron 513 of Marine Aircraft Group 33 of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing — participate in the bacteriological warfare program. VMF-513 was based on K8, the Air Force base at Kunsan of the 3rd Bomb Wing, whose B-26s had already begun bacteriological operations. VMF-513 was to be serviced by the 3rd Bomb Wing….

Towards the end of January, 1952, Marine night fighters of Squadron 513, operating as single planes on night armed reconnaissance, and carrying bacteriological bombs, shared targets with the B-26s covering the lower half of North Korea with the greatest emphasis on the western portion. Squadron 513 coordinated with the 3rd Bomb Wing on all these missions, using F7F aircraft (Tiger Cats) because of their twin engine safety.

K8 (Kunsan) offered the advantage of take off directly over the water, in the event of engine failure, and both the safety and security of over water flights to enemy territory.

For security reasons, no information on the types of bacteria being used was given to the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. In March, 1952, General Schilt was again called to the 5th Air Force headquarters and verbally directed by General Everest to prepare Marine Photographic Squadron One (V.M.J.1 Squadron) of Marine Aircraft Group 33 to enter the programme [sic]….

The missions would be intermittent and combined with normal photographic missions and would be scheduled by the 5th Air Force in separate, top secret orders….

During the latter part of May, 1952, the new Commanding General of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, General [Clayton C.] Jerome, was called to 5th Air Force Headquarters and given a directive for expanding bacteriological operations. The directive was given personally and verbally by the new Commanding General of the 5th Air Force, General Barcus.

On the following day, May 25, General Jerome outlined the new stage of bacteriological operations to the Wing staff at a meeting in his office at which I was present in my capacity as Chief of Staff….

The directive from General Barcus, transmitted to and discussed by us that morning, was as follows:

A contamination belt was to be established across Korea in an effort to make the interdiction program effective in stopping enemy supplies from reaching the front lines. The Marines would take the left flank of this belt, to include the two cities of Sinanju and Kunuri and the area between and around them. The remainder of the belt would be handled by the Air Force in the center and the Navy in the east or right flank….

During the first week of June, Squadron 513 started operations on the concentrated contamination belt, using cholera bombs. (The plan given to General Jerome indicated that at a later, unspecified date — depending on the results obtained, or lack of results — yellow fever and then typhus in that order would probably be tried out in the contamination belt.)

Squadron 513 operated in this manner throughout June and during the first week in July that I was with the Wing, without any incidents of an unusual nature….

I do not say the following in defense of anyone, myself included, I merely report as an absolutely direct observation that every officer when first informed that the United States is using bacteriological warfare in Korea is both shocked and ashamed. I believe, without exception, we come to Korea as officers loyal to our people and government and believing what we have always been told about bacteriological warfare — that it is being developed only for use in retaliation in a Third World War.

For these officers to come to Korea and find that their own government has so completely deceived them by still proclaiming to the world that it is not using bacteriological warfare, makes them question mentally all the other things that the government proclaims about warfare in general and in Korea specifically.

None of us believes that bacteriological warfare has any place in war, since of all the weapons devised bacteriological bombs alone have as their primary objective casualties among masses of civilians — and that is utterly wrong in anybody’s conscience. The spreading of disease is unpredictable and there may be no limits to a fully developed epidemic. Additionally, there is the awfully sneaky, unfair sort of feeling dealing with a weapon used surreptitiously against an unarmed and unwarned people.

I remember specifically asking Colonel Wendt what were Colonel Gaylor’s reactions, when he was first informed and he reported to me that Colonel Gaylor was both horrified and stupefied and said he’d like to “turn in his suit.” Everyone felt like that when they first heard of it, and their reactions are what might well be expected from a fair minded, self respecting nation of people.

Tactically, this type of weapon is totally unwarranted — it is not even a Marine Corps weapon — morally it is damnation itself; administratively and logistically as planned for use, it is hopeless; and from the point of view of self respect and loyalty, it is shameful….

Security was far the most pressing problem affecting the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, since the operational phase of bacteriological warfare, as well as other type combat operations, is controlled by the 5th Air Force.

Absolutely nothing could appear in writing on the subject. The word “bacteria” was not to be mentioned in any circumstances in Korea, except initially to identify “Super Propaganda” or “Suprop.”

Apart from the routine replenishment operations of Squadron 513, which required no scheduling, bacteriological missions were scheduled by separate, Top Secret, mission orders (or “FRAG” Orders)….

Only those who absolutely needed to know about the program to ensure its efficient functioning, were to be informed. Normally a staff officer and his assistant are cognizant of all matters within their section, so that if one officer is absent, the other can attend to any pertinent matters. It was not so with this program. If the cognizant officer was absent and an urgent matter came up, the question was to be taken to the Chief of Staff, Executive Officer, Commanding Officer or other senior staff officer. The reason I opposed informing the Wing Medical officer was that the program could function without his knowing about it.

The entire subject was mentioned only in official business when it was necessary to discuss it, and then only behind closed doors and in guarded tones and terms. No “Suprop” mission was mentioned in the General’s daily staff briefing.

Violations of security in this matter, like violations of security of any regulation of equal importance, were to be the subject of a general court martial….

Selection from Flyers’ Statements: Colonel Andrew J. Evans, Jr., USAF

Colonel Andrew J. Evans, Jr., age 34 at time of capture, had relatively high ranking positions with Air Force Joint Staff. From July 1948 to June 1950 he was joint secretary of the Joint Logistics Plans Group in the Joint Staff. Subsequently, he served as assistant to the Executive to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force from July 1950 to July 1951. In Korea, he served as Deputy Commanding Officer of the 48th Wing, Fifth Air Force from November 1952 to March 15, 1953, then briefly as Deputy Commanding Officer of the 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing until his plane was shot down on March 26, 1953. Evans stated that he flew 8 germ warfare missions.

From Col. Evans’ deposition, dated August 18, 1953:

Actually, my first contact with germ warfare and the fact that it might be used in Korea, was in January 1951. At that time I was assistant to B/Gen. Grussendorf, the Executive Officer to Gen. Vandenberg, Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force. As the Executive officer, Gen. Grussendorf, was in charge of the administrative handling of the office of the Chief of Staff. Naturally he came into contact with some matters of a highly classified nature. One day we were talking of events in Korea. We were speaking of the reversal of events there since the Chinese forces entered the war, when he informed me, “This is so, but last month [Dec. 1950] the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the preparation for, and possible use of, germ warfare in Korea. The Research and Development Command was directed to complete this project by the end of 1951. It may be that this program will have some effect on the future course of the war….

In the middle of September, 1951, we received two one hour lectures from a research analyst of the Research and Development Command in Baltimore, Maryland. I cannot recall the name of the lecturer but he was active in the germ development program.

These lectures were on the many types of germ diseases that were being experimented with and the means of dispersing them. There were many types being tested, but his names given for them were too technical for most of us. Those I remember, in simple language, were Spotted Fever, Typhus, Cholera, Malaria, Sleeping Sickness, and Undulant Fever. He covered such things as what each agent was used against, the effects on human beings and plant life, the number required in an area for deadly effects, and the expected lifetime of each germ when dropped. He said that both germs and germ infected insects were being experimented with.

Delivery was to be made by means of either bombs or tanks. The bombs were to use either impact or VT fuzes, and they were trying to make the bombs disintegrate when exploded. Two types of tanks were being tested — one type to be used as a drop tank, and the other type to contain a germ solution for spraying, similar to a chemical warfare tank. He said that they were progressing satisfactorily and and hoped to be able to run experiments in Korea in the future….

I went to Korea on the 9th of November and reported in to B/Gen. Warburton, the Deputy Commanding General of the 5th Air Force in the morning of November 10, 1952….

Close support of our ground forces was described as a constant function of the 5th Air Force units going on simultaneously with other operatoins. [sic]

Gen. Warburton followed this discussion of the regular mission of the 5th Air Force with a briefing on its germ warfare activities. He said that germ activities for it started with the decision of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in October, 1951, to run experiments with the weapons that had then been developed by the Air Force. The 3rd Bomb Wing of B-26’s at K-8, along with B-29’s of the Far East Air Force Bomber Command, conducted these first experiments in November, 1951. Following the success of these tests, formal approval was given and regular missions started in December, 1951. Not long after this, in December also, the Joint Chiefs of Staff made the further decision to include germ missions north of the Yalu in the program which was put into effect in January, 1952.

From this beginning, he mentioned also that these activities had started on a small scale and gradually built up to include all of the units into the program. The supply of agent material and weapons was a limiting factor in this early build up. He said the Marines were also included in the activities; but he did not give me any facts on them….

In describing the activities of each Wing at the time of our discussion. Gen. Warburton said that all Wings of the 5th Air Force were then participating. The B-26’s had their germ operations principally at night along the main lines of communication of the enemy south of the Chong Chong River. The fighter-bomber Wings were performing daytime germ missions only against targets all over North Korea, but they, too, remained principally south of the Chong Chong River. The F-86’s were operating in the area between the Chong Chong and the Yalu Rivers for the most part. There was, however, nothing to prevent 5th Air Force operations from assigning targets to any of the units which did not conform to those areas….

He told me that the germ materials being used in Korea were produced in a factory near Tokyo and flown to Korea where they were loaded into bomb cases and tanks for use. Germ bombs, which were of a 500 lb. and 1000 lb. GP size, were being used the most, but the F-86’s were also using drop tanks and some of the unit had recently started using a spray tank carrying a liquid solution similar to the chemical warfare spray tank.

In discussing the scheduling of germ missions in the 5th Air Force, Gen. Warburton said that a daily operations order was issued to all the Wings….

In closing his discussion with me, Gen. Warburton pointed out that security in germ operations was still very important even though the Communists have exposed them, and that joining the program entitled a heavy responsibility….

Starting with a review of the background, [Col. Rogers, the Commanding officer of the 49th Wing] said that they began participation on a small scale in February, 1952, following the tests and formal beginning by the B-29’s and B-26’s….

And he also mentioned that the 49th Wing started their germ sorties north of the Yalu in April, 1952.

In speaking of the scale of these early germ operations, he said that they were only occasional at first but they increased along with the supply of germ bombs. Along with the receipt of the increased supply of germ bombs, they had used those pilots with former experience in germ operations to give talks in ground school on the subject so that sufficient trained pilots were ready when needed.

Up until the 1st of October he said that the 49th Wing was using only germ bombs in its germ warfare operations, but from that time on they also started using a new weapon, a germ solution spray tank. He described these tanks as being of a 120 gallon size similar in appearance to a fuel tank. They were carried under the fuselage of the aircraft on the same racks where the bombs were carried. When operated from the cockpit they released a continuous flow of germ solution from the rear of the tank which covered the target area with germs. The use of these spray tanks as well as bombs, he said, increased the scale of activities in his Wing.

The manner of performing these missions which he described to me was for the Wing usually to have the germ warfare flights integrated into the regular schedule of operations that came daily from 5th Air Force…..

On about the 19th of November, 1952, General Vandenberg, the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force visited our Wing along with Lt. Gen. Barcus, the Commanding General of the 5th Air Force….

At that time the discussion was principally on what could be done to stop the continuing flow of supplies to the Communist forces. We were all aware that in spite of our efforts supplies were constantly being built up, mainly by truck transport at night. B-26’s had been operating against this traffic at night, but their operations were not enough.….

[General Vandenberg] said that he had also been discussing with Gen. Barcus the germ warfare operations of the 5th Air Force. Expressing his disappointment with the results thus far being achieved in germ warfare, he said that he wanted good use to be made of night fighter bomber work for germ operations….

Gen. Barcus held a conference of all fighter-bomber commanding officers at 5th Air Force Headquarters in Seoul the next day at 1000. The purpose of the conference was to work out further plans on using fighter bombers at night based on Gen. Vandenberg’s directive….

The germ weapons that the 5th Air Force decided to employ at night were to be both 100 lb. and 500 lb. size germ bombs, and germ spraying tanks….

The tactics for the employment of these weapons were left up to each of the Wings. However, it was decided that spray tanks were to be used principally along the highways, regardless of whether traffic was observed on them or not. In this way germs would be placed along the route of marching enemy forces or on personnel areas along the highway. Bombs were to be used principally on truck traffic observed and on main supply centers. In this way the supplies being transported to the front would be infected with germs….

In discussing our tactics to be used we decided that the tactics for bomb carrying aircraft, whether GP or germ, would be the same. Flying over the target areas we were to maintain a 15,000 feet altitude for our observation of the area and traffic below. When we observed a line of truck headlights below, we were to position ourselves directly behind them, make our bomb run along the long axis of this traffic and release our bombs at about 5000 feet. The procedure for using spray tanks would be to locate the exact position of a highway, either visible in the moonlight or by the headlights of trucks, drop down to 2–3000 feet and release the germ solution s you flew along over the highway….

The first mission I participated in on which germ bombs were carried was about December 28, 1952. I was leader of a section of eight aircraft from the 7th Squadron….

I directed that the last four aircraft would be the ones to carry the germ bombs, each one of the four to carry one 1000 lb. GP bomb and one germ bomb. The first four aircraft were to carry two 1000 lb. GP bombs each, and all fuzes were to be impact. I discussed the target again and assigned sections of it to each pilot as an aiming point, giving each of the germ bomb carriers the four largest buildings in the area. Then I directed that aircraft would bomb individually from string formation with a bombing altitude of 4000 feet, and rendezvous over a bend in the river about 15 miles from the target. The actual performance of the mission followed exactly the instructions in this briefing.

Then, in January, I participated in three missions carrying germ bombs. Two of these were a part of a major operation against the Sinanju area.

It was on the 8th of January that Gen. Barcus called a meeting of Wing Commanders to discuss planning for a major operation against the area around Sinanju. As Colonel Rogers was absent on leave at that time, I attended the meeting as acting Wing Commander….

As most of the supplies were moving along the main supply route running from Antung to Pyongyang across the Taeryong and Chong Chong rivers near Sinanju, this area was determined to be the most strategic point in all North Korea for interfering with the movement of supplies. It directed that the 5th Air Force run a maximum effort operation against the bridges crossing the two rivers, and at the same time to include the dispersal of germ warfare agents in the area surrounding the bridges….

During the period I was with the 49th Wing, Col. Eppright, the 5th Air Force Deputy Chief of Staff for material visited K-2 quite often. From several talks I

had with him on these visits, I learned several things about the supply and maintenance of germ warfare weapons.He told me that the tanks, bomb cases, and fuzes were produced in the United States and shipped to Korea. However, the agents themselves were produced in a factory near Tokyo. They were packed in containers and flown to the two germ weapon dumps in Korea, one in Pusan and one in Taegu.

As near as I can recall. Col. Eppright told me once that the dump at Pusan supplied the 17th, 3rd, 474th, and 18th Wings. The one at Taegu supplied the 49th, 58th, 8th, 4th, and 51st Wings.

My personal feelings on my participation in the USAF germ warfare program are now very clear. I am ashamed that I had any part in it. It was a crime against all humanity and should be outlawed for all time from the armaments of nations….

Selection from Flyers’ Statements: Colonel Walker “Bud” Mahurin, USAF

Air Force Colonel Walker Mahurin was unusual in a number of ways. He was the only captured flyer to later write an autobiography, Honest John, which included details of his capture, a cover-story about the use of the code-word for BW — “Maple Special” — as well as his interrogation, and the tense aftermath of having signed a confession when he was repatriated back to the United States after the Korean War armistice.

In his book, Mahurin made claims that were demonstratively untrue. With respect to his “confession,” Mahurin, who like Schwable indicated he had suffered under isolation and forced positions, said, “to try and relate fleas, flies and mosquitoes to what went on at Camp Detrick… or Fort whatever… is preposterous…. They didn’t know what they were doing [there]…. Everything I wrote was completely implausible, and I knew that anyone who saw my statements in print would find them laughable” [p. 13, Honest John].

One can compare Mahurin’s ridicule about the use of insect vectors for BW to a discussion I discovered recently took place at a February 22, 1948 meeting of the U.S. Chemical Corps Technical Committee. Minutes for the meeting reveal that while Chemical Corps had not yet taken up insect vector BW research, “other government agencies” had under cover of “insect control.”

At the same meeting, Dr. N. Paul Hudson, who served on the technical committee, but was also head of the Microbiology Department at Ohio State University, argued, “The sabotage phase of BW seems to be the most promising at this time, since that phase will use the most natural channels, water supplies, etc.” [p. 5] In the end, the meeting participants decided that, utilizing insect specialists at the Army Chemical Center, “Attention should be given to the utilization of insects as vectors for BW agents” [p. 2].

By his own account, Mahurin had friends in the CIA. As I’ve described elsewhere, his initial capture was a source of interest to CIA analysts examining decrypted communications from North Korean and Chinese military units. The late Canadian historian Stephen Endicott discussed Mahurin’s role, relying on the latter’s book, as well as an interview done by Professor Mark Selden at Mahurin’s home in July 1976.

Having achieved some fame as a World War II “flying ace,” when the Korean War broke out Mahurin was Assistant Executive to Air Force Secretary Thomas K. Finkletter. He was shot down over North Korea on May 13, 1952.

From Col. Mahurin’s deposition, dated August 10, 1953:

The first time I became acquainted with Bacteriological Warfare was when I received instructions in the month of November 1950 from my superior Colonel Teal, the Deputy Executive of the Office of the Air Force, to pay a visit to Camp Detrick, Frederick, Maryland.

Colonel Teal explained to me that the Air Force was conducting experiments at Camp Detrick to determine the best methods to carry and release weapons of germ warfare from aircraft….

Colonel Teal brought out the point that the high military leaders such as General Bradley, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Vandenburg the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, General Collins the Chief of Staff of the Army, and Admiral Sherman the Chief of Operations of the Navy considered that germ warfare weapons were effective and yet inexpensive and should be developed to take a place in the general field of weapons. Although the Korean War was progressing satisfactorily at that time the future was unknown so the Bacteriological Warfare program was being brought into the experimental development stage because of the uncertainty of future events….

[Mahurin goes on to say Air Force officials sent him and others officers to then-Camp Detrick to be briefed and offer any insights they might have about the BW program from their Air Force careers. — JK]

Colonel Teal impressed upon me that the project was considered to be “Top Secret” in nature, and investigations were being carried out with the utmost secrecy at Detrick.

It’s worth noting that in his interview in U.S. News & World Report, mentioned above, Col. Mahurin stated he had made up the names he used in his confession. “I used names of officers who were dead or of officers who had retired from the service years ago, things like that. So you knew if anybody with any brains examined the confessions, they would know it was ridiculous to start with….” (pg. 21).

Hence, there should be no Colonel Teal. But there is. His full name was Colonel Gilbert E. Teal, and he was identified in a January 1951 Congressional report (pg. 109) as the “Acting Executive, Officer of the Secretary of the Air Force” in Washington, D.C., just as Bud Mahruin said he was. So much for “ridiculous” claims!

I made my visit to camp Detrick, Frederick, Maryland in the middle of the month of November 1950….

[Mahurin described the 8-ball experimental chamber, also greenhouses at Ft. Detrick.]

The experimental bombs themselves were being constructed at the center [of the 8-ball chamber]. Once the best design had been decided upon by the center the bombs could be made on a mass production scale.

At the conclusion of my visit my guide told me that there were many types of bacteria under consideration. The germs could have a harmful effect on humans, animals, and crops. The desired result, he said, would be to cause sickness and reduce the capacity to work or fight….

[Mahurin then described his advice about adapting the BW weapons for use with high-speed aircraft, which he thought was feasible.]

I was promoted to Colonel in February 1951, and in April was made Commander of the 1st Fighter Interceptor Group, Victorville, California, U.S.A.

In the last week of October 1951 I received notice by teletype message from Headquarters, USAF that I was to report to Major General Saville who was working under the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, USAF as soon as possible. When I reported to General Saville, he called Brigadier General Cullen and Colonel McKnickle to come into his office.

General Saville conducted the meeting by saying, “General Vandenburg is ordering the shipment of seventy five F-86 E aircraft to Korea to replace the F-80 aircraft of the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing. You, Mahurin, and you, McKnickle are going to be in charge of the project.” General Saville explained that the aircraft were to be used in connection with a germ warfare program in Korea.

General Saville said that instructions had been received from high authorities of the Department of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff that a limited campaign of germ warfare would be started in Korea. The instructions had reached the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, USAF after passing through the office of.the Chief of Staff of the Air Force General Vandenburg. The entire matter had been received in the Chief of Staff’s office, then separated into pieces and sent to various staff agencies for appropriate action. There were only a few people who knew of the entire program at that time.

The objective of the germ warfare program was to use these weapons under actual field conditions in Korea to test the effect. Also the weapons might be used later in the Korean War on an expanding scale depending on the conditions at a later date. Containers for different types fit aircraft were to be tried out and the weapons would be dropped over different types of terrain and under all kinds of climatic conditions. It was hoped that the peace talks might be influenced and that a satisfactory outcome might result. By this time the Air Force had developed an external link for the F-86 that could carry insects infected with various diseases. These tanks would be tested by the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing under actual combat conditions….

General Saville explained that Colonel McKnickle’s part of the project would end when the shipment departed from the United States. However, I could expect to receive orders transferring me to Korea after the movement was completed. He added that I would report to General Weyland, the Commanding General of Far Eastern Air Force when I arrived in Tokyo, Japan….

When General Saville closed the meeting he cautioned both Colonel McKnickle and me about security and requested that we keep what he told us about the Germ Warfare program just to ourselves.

The shipment of aircraft and personnel was to be completed on the 5th of November 1951, so I arranged to meet Colonel McKnickle at Alameda on the 4th of November to carry out our inspection.

On the 4th of November 1951 I arrived at Alameda Naval Air station. Colonel McKnickle. was waiting for me, having arrived the night before from Washington, D.C. We immediately set out on our inspection. Of course we were the only people who knew of the germ warfare program and its background. When we finished our inspection we sent a teletype message to General Saville stating our findings and Colonel McKnickle departed by aircraft for Washington to give General Saville a personal report. For my part I returned to the 1st Fighter Group to wait for further instructions….

My date of departure from the United States was to be the 15th of December, and upon arrival in Japan I was to report to General Weyland, the Commanding General of Far Eastern Air Force (FEAF), for further instructions and assignment. I then left the United States by aircraft bound for the Far East….

When we met General Weyland he explained that he had received sealed orders from the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff concerning the bacteriological warfare program. He said that the directive indicated that the F-86 would start initially on a small scale with a possibility of expanding it at a later date. He said that other types of aircraft such as the B-26 would also be used and the F-86’s of the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing would also do their part. General Weyland then talked to us about the germ warfare program as it applied to the F-86. He stated that he expected our germ warfare experiments to start as soon as possible, and we would receive our germ tanks by air lift from Taegu, Korea…. He told us that he had talked to General Everest, the Commanding General of 5th Air Force over the telephone and he was sending us on to talk personally with General Everest. Our duties would be fully explained to us by General Everest. He said that it would be our responsibility to see that they were carried out properly….

On December 20, 1951 our aircraft landed at K-16 (Seoul) at 3 O’clock in the afternoon. The three of us, Major Schaeffer, Major Chandler and myself were taken by jeep to 5th Air Force Headquarters. When we reported to the office of General Everest, the Commanding General of 5th Air Force, his secretary took us to the General immediately. In the office the General introduced himself and presented Colonel Meyers, the Operations Officer of 5th Air Force. The General who had been expecting us then briefed us on the part the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing would play in the germ warfare program. He explained that the three of us were to fit into the general routine of the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing as quickly as possible….

General Everest then explained that 5th Air Force was going to start a limited campaign of germ warfare. Our jobs would be to brief the pilots when 5th Air Force directed us to do so. In the meantime we were to keep the program as secure as possible. We would soon receive orders from 5th Air Force to begin the attacks, so we should help the Wing make the necessary preparations.

Colonel Meyers stated that the germ tanks for the F-86 aircraft would be shipped to us from Taegu for the distribution facilities had been established there. The Material Section of 5th Air Force under Colonel Ferguson would handle this shipment along with other shipments to the Wings involved in the bacteriological warfare program. Trained personnel were on hand at Taegu….

Selection from Flyers’ Statements: Major Roy H. Bley, USMC

On July 8, 1952, U.S. Marine Corps Major Roy H. Bley was Frank Schwable’s co-pilot on their doomed flight returning to base. As Bley was an ordnance officer, his deposition to his captors focused much more intensively on the issue of supply and storage of biological munitions, as well as training for handling and loading such weapons. Bley died in 2004.

Each of the flyers’ confessions adhered closely to the area of expertise associated with their rank and position, something CIA analysts examining the confessions noted in a February 1953 secret report, “BW and the Korean War.”

From Major Roy Bley’s deposition, dated January 21, 1953:

I arrived in K-3 [Pohang Air Base], Korea on the 28th of May, 1952 and was assigned as 1st MAW Ordnance Officer on the following day, the 29th. The previous Wing Ordnance Officer had departed for the States in the early part of May, 1952, leaving the job to be handled by a M/Sgt. [Master Sergeant], McGarry, the Ordnance NCO, who had worked for him, and who had been on that job for several months.

On the night of the 2nd of June, McGarry and I were working alone in the Ordnance Section of the G-4 (Logistics) Office discussing normal, routine ordnance matters, and he briefing me on the details, problems and procedure, of my job. That night he told me the main facts about germ warfare as conducted by the Wing at that time.

He reported that VMF-513, Marine Night Fighter Squadron 513 located at K-8, was dropping germ bombs for the 3rd Bomb Wing there. They had started dropping them early in 1952. The ordnance men from VMF-513 had been trained and assisted in the use of germ bombs by Special Weapons personnel of the 3rd Bomb Wing and the Squadron’s supply of the weapons was made directly from the K-8 bomb dump, operated wholly by Air Force personnel.

Later, in March, 1952, VMJ-l, (Marine Photographic Squadron one of Marine Aircraft Group 33) also began dropping germ bombs. Ordnance men had been assigned to the Squadron from the group for that specific purpose, forming a Special Weapons Unit, and had been given two weeks training prior to the Squadron’s first use of the bomb by an Air Force Special Weapons team sent to their base from K-8. This team consisted of two officers and six enlisted men and had instructed the ordnance men on handling procedures, storage and security methods. Then the team had remained with the squadron for two or three weeks after the squadron had initiated its use, to supervise and continue their instructions.

The first supply of germ bombs for Squadron VMJ-1 had been ordered from the 6405th Air Support Wing of the Air Force located in Taegu, and picked up at their Ulsan Ammunition Supply Squadron (543rd) Dump by the ordnance men of VMJ-1 accompanied by members of the Air Force Special Weapons team.

[Author’s note: As a matter of interest, both the 6405th Air Support Wing and the 543rd Ammunition Supply Squadron, were real entities that existed just as Major Bley described them, as noted on pg. 71 at this USAF webpage. This is pointed out here as only one example out of many of the kinds of corroborating information available by which to judge these documents.]

Security methods, especially in its first stage of use in K-3 (Marine Aircraft Group 33’s base at Pohang, Korea) were very stringent. The only persons who knew of its use were some members of the Wing Staff, the Group and Squadron commanders, pilots flying the missions, the Group Bomb Dump Officer and Ordnance men who made up the Special Weapons team and who actually handled all the transportation and did the loading of the aircraft.

The supply of the germ bombs was handled by the VMJ-1 Special Weapons Unit who went directly to the 6405th A.S.W., with a priority secret despatch.

On the morning of the 5th of June, 1952, Colonel Clark, logistics officer of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, called me into his office where he was alone and asked about my progress in becoming familiar with the ordnance job…. “Now, Bley, for the main reason I called you in here. It’s to discuss the Wing’s special weapon, project, the use of the germ bomb”. After he sat down again at his desk he asked: “Has McGarry discussed it with you?” I replied that he had, briefly. He then said: “In order to bring you up to date on its use out here, I’ll give you a brief history regarding its previous use”.

The Air Force started dropping the bombs, upon order from their High Command in Washington in the early winter of 1951, first with the B-29s based in Okinawa, followed by the 3rd Bomb Wing’s B-26s at K-8 (Kunsan Korea). Then fighter types were also included into the use of them too, and that included Marine Squadron 513, also based at K-8.

This Squadron, attached to MAG-33, using F7F (Tiger Cats) aircraft, was included in the project by the Air Force for these reasons: they were a Night Fighter Squadron and could drop the bombs with a great deal of security; they were based at K-8 where the supply of bombs was available; and the Air Force High Command decided that some experimentation and familiarization work by a Marine Squadron would be very helpful to marine aviation and themselves should the germ bomb be used on an increased scale. This experimentation and familiarization would not only afford experience to flight crews but also to the ordnance men who would help the Air Force special, weapons personnel in handling details and procedures.

Squadron 513 started using germ bombs right after the 1st of the year, 1952, and then Squadron VMJ-1 also was added to the program, by the Air Force in March, first, because they were a utility outfit doing mostly photographic work and could drop the bombs without being suspected, second, during their normal work they covered all parts of North Korea, and third, special weapons personnel were available at K-3, their base, to form a nucleus of handling personnel required.

Then he paused and asked: “What do you think of the use of the germ bomb?” I said: “Sir, it’s not only against my own principles but it would also certainly leave a black mark against the Marine Corps’ reputation”. The colonel said he didn’t approve of its use either, nor did anyone else in the Wing but we were ordered to do so by higher authority and there was nothing to do but obey our commands.

Colonel Clark then told me that General Jerome, Commanding General of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, had attended a conference at the 5th Air Force Headquarters during the latter part of May and a plan had been introduced to him where the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing was to participate more fully in the use of germ weapons. Then when General Jerome returned to K-3 he had called a staff meeting including the Assistant Commanding General, Lamson-Scribner; the Chief of Staff, Colonel Schwable; intelligence officer, Colonel Stage, to the best of my memory; operations officer, Colonel Wendt and himself. General Jerome had discussed the plan in detail and had outlined the tasks and missions for the various G-sections to do. During this conference it was decided that I, as Wing Ordnance Officer due to arrive three days later, would have to be informed of the plan, for I would have to handle many of the details for the logistics section.

Colonel Clark then pointed out that during the conference the target areas were also discussed. It was decided by JOC (Joint Operational Center) that a contamination belt was to be established deep behind the enemy lines, across the peninsula of Korea and covering the enemies’ main routes of transportation.

So both of our Groups, Marine Aircraft Group 33 and Marine Aircraft Group 12 [MAG-12], were included in the plan, Squadrons VMJ-l and VMF-513 of MAG-33 were to continue on an increased scale, and the F9F (Panthers) Squadrons of MAG-33 were to get prepared to use germ bombs and be on a standby status, ready should they also be ordered to drop them by JOC. The AD’s (Skyraiders) of MAG-12 were to start immediately on a small scale by flying to K-8 for their supply of germ bombs and operating from there until some special dispensers arrived from the States and then they would operate on a large scale with their supply of bombs to be from the bomb dump of their own base, K-6 at Pyongtaek….

On the 9th of June, McGarry and I drove to see the MAG- 33 bomb dump officer and inspected his facilities for the germ bombs, which were satisfactory. He explained to me that the bombs were requisitioned by the Special Weapons Unit direct from the Air Force.I advised him to make more storage space available because the usage rate was to be increased and will probably have to handle two or three times as many bombs as he previously had.

On the 13th of June I went to K-6 to inspect the MAG-12 bomb dump and to talk to the Group Ordnance Officer about his plans for his eventual storage of germ bombs there.

I asked him if he knew of the proposed use of the Special Weapon, the germ bomb, by MAG-12. He replied that he had been told of it by Colonel Gaylor the Group Commander about ten days before. Colonel Gaylor had told him that the supply of bombs was not to be established yet for a few weeks. Before the supply of bombs were to be handled at K-6, the Group would have to have some men trained in handling procedures. Colonel Gaylor had ordered him to select about ten men from his bomb dump crew, men who were reliable and who he considered would be able to pass a secret security classification check, but not key men in his regular bomb handling crew, and send them to K-8 where they could be given on-the-job training by the 3rd Bomb Wing. These men had been sent to K-8 on the 11th of June for a period of about four weeks.

I checked on storage arrangements and security of information. I reported how Squadron VMJ-1 drew their germ bombs but said I’d have more information on that after Colonel Clark and I conferred with the Air Support Wing personnel in Taegu in a few days.

Finally I gave him instructions to go down to K-3 and see the set-up there and also to go to K-8 when he found time to see their storage methods.

On the 16th of June I flew to Taegu to confer with the 6405th Air Support Wing [ASW] regarding the increase in supply of germ bombs to the 1st MAW. Colonel Clark was unable to come with me. The conference was held in the office of the Commanding Officer of the 6405th ASW, where I also met the ordnance officer.

I learned that the 6405th ASW had been supplying the germ bombs to the 3rd Bomb Wing at K-8 since December 1951, at first in small quantities and then in larger deliveries. Delivery to K-3 had commenced in March of 1952.

The Commanding Officer stated to me that FEMCOM (Far East Material Command) had notified him about the 1st of June that the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing was to increase its use of germ bombs at K-3 and was also to establish a germ bomb supply at K-6.

I went over all the details of requisitioning and delivery, coding, types and reports.

We agreed that Squadron VMJ-1 would continue to send their own requisitions for germ bombs until the germ bomb dump was established at K-6 [airfield at U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys, south of Seoul, HQ for U.S. Marine Air Group 12 — JK], and then all requisitions for both Groups would be made by me from 1st MAW Headquarters. That would be around August. I passed all these decisions on to Colonel Clark and the other officers concerned verbally.…

On the 7th of July, Colonel Clark notified me that he was calling a conference of MAG-12 and MAG-33 Logistics and Ordnance Officers and some officers of the Special Weapons Unit of Squadron VMJ-1 to be held on the 10th of July to discuss the problems arising out of the increased use of germ bombs. Next day I made a trip to K-6 with the 1st MAW Chief of Staff, Colonel Schwable and had a preliminary talk with the Group 12 Ordnance Officer. He told me that he would be ready to establish a germ bomb facility there as soon as the team to handle them had completed their training at K-8. This would be around the 12th of July.

On this same day, July 8th, 1952, on my way back to K-3 from K-6 with Colonel Schwable, we lost our course and were shot down by ground fire behind the front lines in North Korea.

Thank you so much for your dedication to this topic.

Do you know where I can read about the effects these bombs had on Korean populations? Either your work or others, preferably free to read (e.g. internet links)?