The Lights Were Blinking Red

Just as the U.S. was beginning a secret program dropping biological bombs over North Korea & Manchuria in early 1952, Canadian & British scientists — and the FBI — were aware something was afoot

Very few people realize that there was a secret “tripartite” agreement between the United States, Canada, and Great Britain to collaborate on the development of biological weapons (BW). The collaboration began during World War II, was renewed in 1947, and presumably lasted until the U.S. formally ended its biowar program in November 1969. (Whether that program continued covertly is another story.)

It took me awhile to investigate for myself just how important this three-way cooperation had been when it came to the use of biological weapons during the Korean War. I have to thank Editor-In-Chief of The Canada Files, Aidan Jonah, for nudging me to write something about Canada’s role in the whole BW scandal. Thanks to him, I wrote two articles, one that concentrated on the interplay between the Canadian and U.S. programs (see here), and a second article on how Canadian scientists were also used in the cover-up of the U.S. biowar attacks (see here).

It took awhile to read the most important secondary texts, and gather some original documents, so I could immerse myself into the reports, minutes, and letters of the individuals involved. Mine was not an encyclopedic study, but I found enough of interest to buttress my overall understanding of the subject. I’m not sure I will have the wherewithal to do the same with the British program.

In part, that’s because I don’t have access to much of the documentary material, and while I might find some online, I still might have to travel to the UK to really track down what’s needed. That’s why I feel very lucky that the subject had such an excellent historian!

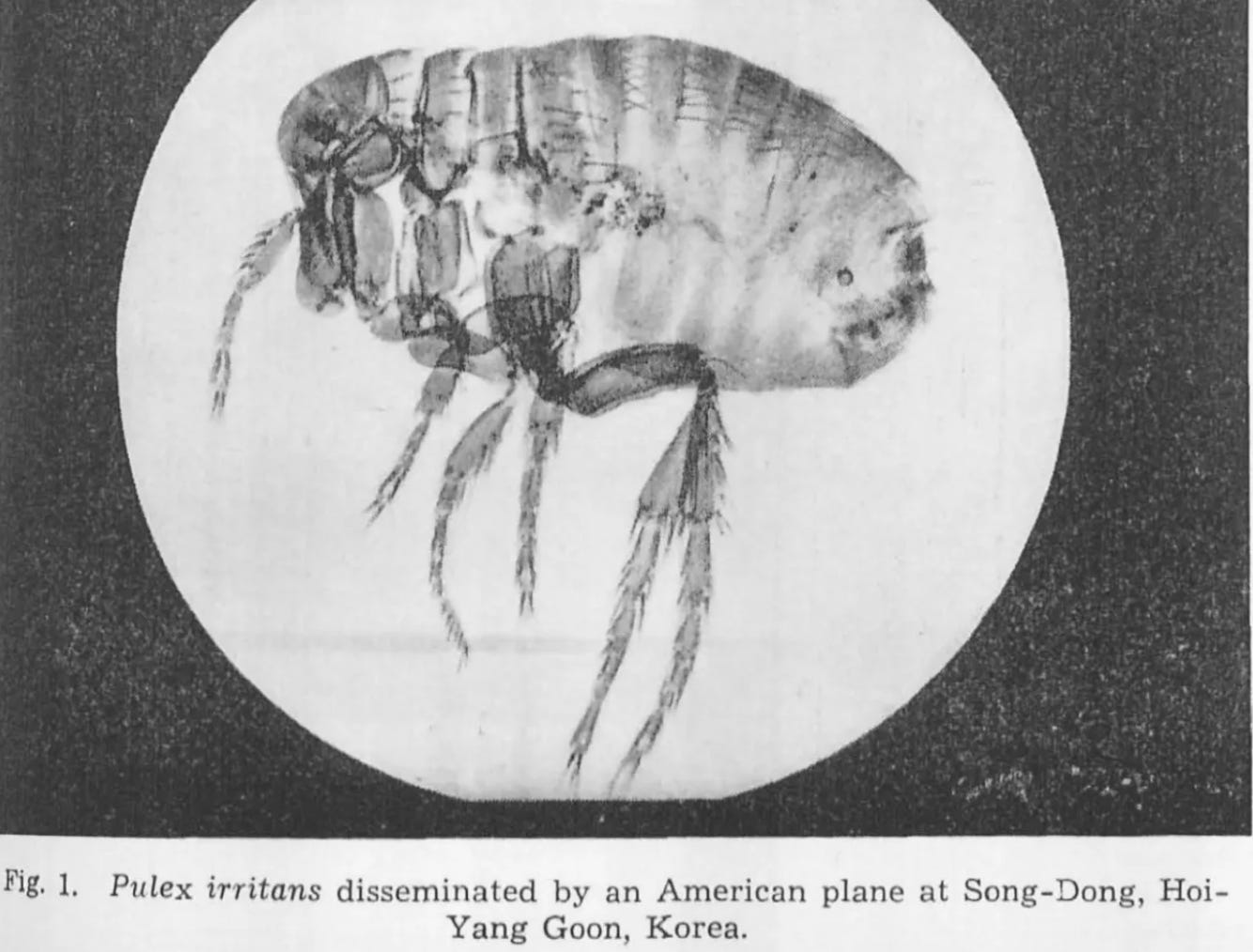

Not that British scholar Brian Balmer’s 2001 book, Britain and Biological Warfare: Expert Advice and Science Policy, 1930-65, doesn’t have its limitations. While it covers the years of the Korean War, it never mentions the allegations made by China and North Korea that the U.S. had in 1951 spread smallpox and other diseases via means typical of sabotage. It never mentions the alleged air campaign, which in late December or early January 1952 began dropping various devices, including re-fashioned propaganda leaflet bombs, over military units and their rear, and on various industrial and city sites, and even in the countryside. The germ war munitions reminded DPRK and Chinese scientists, Communist leaders, and international investigators of the kinds of weapons Japan’s Unit 731 had used on Chinese cities approximately ten years earlier. (See pgs. 11-12 at this link.)

Nor does Balmer even allude to the supposed discovery three years prior to his book’s publication of twelve Soviet documents, half of which were solicited from or written by the former secret police chief, Lavrentiy Beria, and which claimed the Communist BW allegations were a conspiracy by North Korean officials and their local Soviet advisers. I’ve shown elsewhere how these so-called Soviet archival documents are untrustworthy as historical evidence. I hope to have an even more well-documented article on the subject out in a journal soon.

“…the US might use biological weapons in Korea”

But Balmer does describe in some detail the dilemma UK scientists and government bureaucrats found themselves in when the U.S. decided to take a decidedly more “offensive” approach to their BW research in the middle of the Korean War. In fact, Balmer makes clear what I have only previously surmised: the emphasis on offensive BW weapons advanced in 1952 was for “immediate benefit to operational effectiveness.”

As a 1953 U.S. Army Chemical Corps “Summary History” retrospectively summarized the situation only a year earlier (notice the emphasis on the word “immediate”):

Thanks to the world situation of limited war the research and development programs were directed at the immediate completion of short-term developments where immediate benefit to operational effectiveness would result. Although some of these developments were admittedly stop-gap measures, such as the M114 biological bomb, they provided something to use if it were required. At the same time developments were accelerated in order to ease the greatest operational deficiencies. The emphasis was therefore placed on end items in all fields, weapons and munitions for the dissemination of nerve gases (G-agents), and the entire field of biological warfare.

It was my opinion that the “world situation of limited war” was a reference to the Korean War. Balmer proves that I was right (always a pleasing outcome). He wrote the following, describing a controversy in Britain in 1952 over the development of offensive BW weapons vs. research into defensive BW only:

Difficulties over the interpretation of British policy had already emerged after [David] Henderson [chief at the UK’s main BW facility at Porton Down] visited the US and, on his return, expressed concern to BRAB [Biological Research Advisory Board] in March 1952 that ‘American colleagues of long standing had become offensively minded,’ wishing to end the Korean War as soon as possible. Similarly, Henderson felt that the US Services had developed a ‘most aggressive outlook’ with the consequence that their focus had shifted to short-term projects on anti-personnel and anti-crop weapons. BRAB members regarded the divergence in the two countries’ attitudes as problematic and expressed concern at the May meeting of the board that the US might use biological weapons in Korea. (Balmer, pp. 136-137, bold added for emphasis)

It’s not clear from Balmer’s narrative when exactly Henderson visited the U.S., or how much even the UK knew about the U.S. covert BW bombing program. But Balmer’s sourced material corroborates a number of other accounts I’ve read or written about, such as the 1953 Chemical Corps report above. [Update (1/29/24): Conversely, consider the impassioned statement of physicist Samuel Goudsmit, scientific head of the WWII Alsos Mission, to Belgian physicist and concentration camp survivor, Max Cosyns, regarding evidence the latter supplied Goudsmit about U.S. germ warfare in Korea. Writing on June 19, 1952, naysaying claims of U.S. biowarfare, Goudsmit claimed, “If even the faintest rumor of our unprovoked use of biological warfare, or human experimentation, had reached us through our own channels you could have been certain of our vigorous and public protests.”]

But there were other accounts from other countries or U.S. government agencies that have up to now been rarely if ever mentioned:

The Canadian government was hearing much the same about U.S. “offensive” intentions as their UK tripartite partners were, and around the same time. In a December 7, 1951, secret memo from Canada’s Joint Staff to the Chairman of the Defense Research Board [DRB], Canada’s top military officials stated: “The USAF [United States Air Force] is giving serious consideration to the probable use of special weapons, and is, at the present time, making a study, prior to naming a cognizant USAF agent to accept the responsibility of carrying out user trials of these weapons….” Later that month, in another secret memo, dated December 27, J.C. Clunie, the Defence Research Board Senior Staff Officer for Special Weapons, wrote to the Chief Superintendent at the biological and chemical weapons (CW) test site in Suffield, Alberta, “The USAF is giving serious consideration to the probable use of BW and CW Special Weapons.”

In January 1959, John L. Schwab, the former Chief of the Special Operations Division (SOD) at Ft. Detrick during the Korean War, gave a sworn affidavit during the trial of John and Sylvia Powell. The Powells were charged with sedition for reporting on the U.S. biological warfare campaign in 1952–1953 during the height of the Korean War. Schwab told the court that from January 1, 1949 until the armistice that ended the Korean War, “the U.S. Army had a capability to wage both chemical and biological warfare, offensively and defensively….” Schwab contended the weapons never left U.S. soil, but there is plenty of reason to mistrust that. One must recall that the U.S. biowar program was top secret. Those suspected of leaking information were threatened with prosecution, or worse.

A November 1950 briefing to FBI Special Agent Jay Newman by an official at the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah included information on the weaponization of smallpox, i.e., “elective culture smallpox strains have been developed against which immunization by vaccination is not effective.” In addition, botulism toxin had also been weaponized, and was “ready for war use.” The Dugway official described how delivery of BW agents via sabotage methods, e.g. poisoning wells and food supply, was quite feasible. In fact, he told SA Newman, who in turn reported the same to J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, that Army scientists had researched use of anthrax, bubonic plague, and psittacosis (parrot fever). They also had developed “at least four strains… with five to ten variations” of brucella melitensis, which causes undulant fever. Newman further reported: “the [U.S. Army] Chemical Warfare Corps is in a position to effectively use these four diseases by covert means and will have perfected methods of distributing them by bombs within a year.”

Corroborating Evidence

A perusal of declassified documents fills out the picture. A former top secret in-house USAF history of the period 1944-51 describes six BW agents “all of which could [by October 1950] be produced in facilities already established or proposed.” [pg. 65 of report; pg. 68 of PDF] These were anthrax, the brucella strains, “Bacterium tularense” (which produces “rabbit fever”), Pasteurella pestis (plague), botulinum toxin and various cereal rust spores. The cereal rust spores, such as wheat blast or rice blast, were to be delivered by bombs that released infected feathers, as developed by John Schwab’s SOD lab at Detrick.

Of the organisms mentioned above, Chinese and North Korean epidemiologists and health officials had maintained they had found evidence of use of anthrax and plague, both delivered by use of insect vectors. It is also worth noting that as early as 1951 the U.S. had already forward positioned biological bombs in Libya and the UK for possible use against Soviet crops, utilizing secret financing to hide the fact from the world.

For me, Balmer’s discussion of the U.S. emphasis on actually using BW in Korea is another data point to join with the others. Of course, the British documents don’t prove the U.S. used BW. The COMINT documents — declassified CIA communications intelligence reports that repeatedly quote encrypted radio intercepts of Communist military forces discussing being attacked by bacteriological weapons — do that.

There is also the oddity that according to Balmer, the Brits were worried about the possibility of the U.S. turning to offensive BW use as late as May 1952, some five months after we know its use had already begun. All I can say here is that discussion of these matters even inside government corridors was seriously hampered by secrecy and very delicate relations between the allied governments and their relevant agencies. Balmer’s history goes into some detail about the problems for Great Britain that revelations of U.S. use of offensive BW weapons would entail for them both diplomatically and politically.

In any case, mainstream histories and journalistic accounts on the issue of BW and the Korean War maintain that while there was ongoing BW research during this period, there was no intention to ever use it, except as retaliation for an enemy BW attack. But in fact, there is plenty of evidence that for those in the know, the U.S. had decided to go the whole hog on BW and test its offensive use during the Korean War. By January 1952, when by all accounts the U.S. BW air campaign had begun, it seems that for both U.S. allies and domestic U.S. law enforcement, the warning signs of the pending germ war campaign in Korea were wildly blinking red.

Thank you for your work. This book is showing as not available in either Kindle and book form in Australia. Any suggestions as to other suppliers besides Amazon?

The evidence trail continues to grow. Good work, Jeff.