Top U.S. General: U.S. Guilty of Nazi-like War Crimes in Korea

In 1950, the U.S. began a review of Nazi War criminals' Nuremberg convictions, ultimately reversing many of them. The ex-commander of U.S./UN forces in Korea argued for clemency for German officers.

The article below is a reedited and expanded version of an article that first appeared at Medium.com in June 2018. This was a period in which Donald Trump, after first threatening military and possibly nuclear attack, was making diplomatic gestures towards the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, aka North Korea). The first summit between President Trump and DPRK’s Chairman Kim Jong Un was held only days after the Medium article posted.

It was a time of some hope for an easing in U.S.-DPRK relations, including perhaps a reduction or even an ending of sanctions against the DPRK, sanctions that UNICEF reported caused acute malnutrition in hundreds of thousands of North Korean children.

Alas, that opening closed, thanks to the diplomatic ineptitude of President Trump, and the ever-present hostility of the bulk of the U.S. national security establishment, including most Democrats and Republicans.

This article is about war crimes, especially U.S. war crimes. But as I read the original article again years after I first posted it, I saw that it was also about a crucial moment in U.S. history, when the American government undertook a rapprochement with the Nazi war criminals from World War Two, and undid the work of the Nuremberg Trials. It is a story that is barely ever mentioned outside of specialist historian essays. I have accordingly expanded that part of the original article, and I think readers will be interested in yet another piece of forgotten history.

This history is crucial when considering the full U.S. backing of Israel’s genocide now underway in Gaza, which is spreading as I type this to Israel-Palestine’s West Bank. Both U.S. presidential candidates are supportive of Israel’s genocide. It is important to not put any illusions in the U.S. government or its performative elections. We must face the future and the fight against oppression with eyes fully open.

As the U.S. moved towards a possible peace settlement with new nuclear power North Korea in the summer of 2018, it remained true that much of what constituted the savagery of the Korean War was, and remains, unknown to most Americans. This is due to historical ignorance or indifference in general, suppression of the subject in textbooks and general discourse, and most of all, ongoing secrecy about certain U.S. government activities.

In an effort to end the years of secrecy, in 2018, at Medium.com, I posted the long-suppressed International Scientific Commission [ISC] Report on Bacterial Warfare in China and North Korea. Authored primarily by famed British scientist Joseph Needham, the report included an executive summary and hundreds of pages of fact-filled appendices. I made it all freely available in clear and searchable format for easy downloading for the first time ever. To date, the post has received over 65,000 views.

I followed this release with two articles based on the ISC report: an in-depth look at a U.S. plague attack on a North Korean village in March 1952, and another article about U.S. anthrax attacks in Northeastern China around this same time.

Better known and less contested than the biological warfare charges is the fact the U.S. conducted a savage aerial bombing campaign over North Korea during the Korean War. According to one source, “During the campaign, conventional explosives, incendiary bombs, and napalm destroyed nearly all of the country’s cities and towns, including an estimated 85 percent of its buildings.”

At least one million civilians died in these raids. But most likely there were many more. The head of Strategic Air Command, General Curtis LeMay, famously said, “Over a period of three years or so, we killed off — what — twenty percent of the population of [North] Korea….”

The U.S. has never owned up to having committed war crimes during the Korean War, or at least that’s what is generally thought.

A Long-forgotten War Crimes Review Board

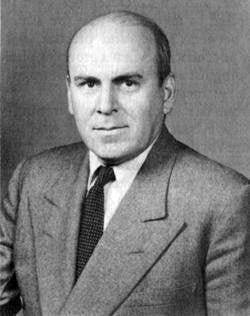

In a long-forgotten admission, General Matthew Ridgway, who was the Supreme Allied Commander for Europe (SACEUR) from 1952-53, told the High Commissioners in occupied Germany — the nominal postwar Allied ruling body, whose U.S. representative at that time was John J. McCloy — that he had conducted crimes as Commanding General of UN forces in the Korean War that were no different than those of German generals who had been tried and convicted by military tribunals after World War II.

Historian David Clay Large wrote, “Ridgway’s stance was emblematic of the growing tendency among Western military men to accept their former adversaries as peers rather than as pariahs (pg. 117).

But of what kinds of crimes were the German generals convicted? McCloy himself outlined them in a letter at the time to Professor Karl Brandt of Stanford University. Brandt had written McCloy in support of a clemency appeal for the military officers convicted of war crimes at Nuremberg and other tribunals, and imprisoned by the Allies in Landsberg Prison.

According to the book Germans to the Front: West German Rearmament in the Adenauer Era, by David Clay Large (University of North Carolina Press, 1996), “McCloy explained that the generals imprisoned in Landsberg were kept there ‘for a very definite reason’ — their compliance with the ‘Führer order to kill all Jews, gypsies, etc.’ McCloy said that he looked upon such generals in the same way he did ‘lawyers and judges who collaborated with the Peoples’ Court, and the doctors who carried out medical experiments in concentration camps.’ All these people, he said, had betrayed their professions….” (Large, 1996, pg. 117, see endnote 1).

McCloy had been besieged by requests from West German citizens for amnesty or pardons for those convicted by the American and Allied tribunals. According to Jeffrey Herf at the New Republic, German historian Norbert Frei has described how eager was a “depressingly broad spectrum of opinion in Adenauer’s Germany — including the leading officials of the Protestant and Catholic churches — to reverse or to ameliorate the results of the Nuremberg-trials period.” According to Large, the types of pressures on McCloy included death threats against his family “from all over Germany” (pg. 116).

The U.S. National Archives (NA) has a collection of the correspondence concerning clemency and petitions for same made from 1947 to 1950, but has not made them available online. The NA has made some material from its collection on WWII war crimes available online, but in general, much remains digitally unavailable, even well into the second decade of the 21st century.

In January 1950, McCloy acceded to the German demands by setting up the Advisory Board on Clemency for War Criminals, part of the High Commissioners office. McCloy appointed David W. Peck, Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division of the First Department of the New York Supreme Court, as Chairman. The board came to be known after its chair as the “Peck Panel.”

Frederick A. Moran, Chairman of the New York State Board of Parole, was appointed second member, and Conrad E. Snow, a legal adviser from the State Department, was third member.

According to the Wikipedia article on David Peck, “The Peck Panel reviewed the clemency petitions of 99 convicts; all were in prison as war criminals in Landsberg. The Peck panel on August 28, 1950, gave its recommendations. In 77 of 99 cases, the panel recommended a reduction of penalties; this included that seven of the 15 death sentences be commuted to imprisonment.” But the final decision on clemency would be left up to McCloy and the other high commissioners in Germany.

In a 1973 oral history interview that has been posted by the Truman Library, Conrad Snow described the Peck Panel’s decisions.

We didn't concern ourselves in the guilt of the criminals for the crimes for which they were found guilty. What we busied ourselves with was the suitability of the sentence to the crime, and in all cases where we recommended a reduction of the sentence we came to the conclusion that the sentence was excessive for the crime involved.

Snow said that McCloy thought “that the sentences were excessive and some leniency should be shown and the Board found that to be so.” Snow tendendiously maintained the panel’s findings were from a “purely legal point of view,” and “not political.”

The Politics of Clemency

An interesting 2021 article at the National World War II Museum website, “The Nuremberg Military Tribunals and ‘American Justice,’” covers some of the legal and political issues surrounding the clemency issue. The article points out that McCloy got advice from within the High Commissioners’ office about the dangers of revisiting the verdicts at Nuremberg.

The article quotes a December 1949 memorandum to McCloy from J.B. Rintels in the General Counsel’s office for the High Commissioners of Occupied Germany. Rintels warned “‘the securing of relief for specified individuals’… in fact constituted ‘an attack upon the original war crimes program as a whole, its underlying philosophies and theses, and its implications involving the culpability of the responsible members of the German government for the offenses of which they were convicted.’”

It is likely that Rintels was referencing “Control Council Law No. 10, Punishment of Persons Guilty of War Crimes, Crimes Against Peace and Against Humanity,” dated December 20, 1945, the document that presumed the legal conditions and rationale for the prosecutions at Nuremberg and other tribunals. It is worth reading as a historical document.

The war crimes sentencing of German high-ranking officers also played a role in the controversy over (West) German rearmament, especially after NATO was formed in April 1949. According to Large, German politician and jurist Carlo Schmid “led a group of parliamentarians” to see McCloy. They wanted the U.S. High Commissioner to commute the death sentences of Nazi officers. “This was urgent, the Germans said, because of the “political and psychological factors at a time when Western Germany was being called upon to make a military contribution to Western defense” against the Soviet Union (pg. 116). In other words, leading Germans threatened to boycott U.S./Western military moves to counter the perceived Soviet military threat if the former Nazi military leaders were not shown mercy.

Schmid, by the way, often portrayed as a liberal Social Democrat and opponent of the Nazis, later spoke out “on behalf of his former legal intern [Martin Sandberger] at the University of Tübingen: ‘Without the onset of National Socialism, Sandberger would have become a reputable, hard-working and ambitious public servant,’” Schmid said.

Sandberger, as “the leader of Special Commando 1a, had made Estonia ‘free of Jews’ and had admitted to the killings of ‘about 350’ communists,” according to a Spiegel article.

But not all Germans in this period were asking for clemency. In late 1950, the vice-president of the German Federation of Labor, Georg Reuter, came to the U.S., where he told officials he was strongly opposed to the commutation of the sentences of the Nazi criminals.

While McCloy had spoken a year earlier about keeping the reins tight on West German politics and eradicating Nazism, on January 31, 1951, the decision was released to commute the death sentences of 21 Nazi war criminals — 15 high Nazi officers, and six former SS troopers involved in the December 1944 Malmedy Massacre of captured U.S. soldiers.

Seven of the death sentences were allowed to stand, though, and these seven went to the gallows five months later. Along with the 21 military and SS criminals who escaped death, McCloy and other U.S. officials freed Nazi arms manufacturer Alfred Krupp and a number of his associates, a move that greatly bothered U.S. allies in England and France.

McCloy was an important figure in American history. Years earlier he had been a key figure in the decision to intern Japanese-Americans in concentration camps. Much later, he joined the Warren Commission on the assassination of John Kennedy at the behest of former CIA chief Allen Dulles. (I will revisit a particular instance of McCloy’s work for the Warren Commission in a future article.)

Taylor Fires Back

According to a recent book published by Yale University Press, After Nuremberg: American Clemency for Nazi War Criminals, by 1958 “High-ranking Nazi plunderers, kidnappers, purveyors of slave labor, and mass murderers all walked free.”

An abstract for author Robert Hutchinson’s book on the clemency controversy explains how “American policymakers’ best intentions resulted in a series of decisions from 1949 to 1958 that produced a self-perpetuating bureaucracy of clemency and parole that ‘rehabilitated’ unrepentant German abettors and perpetrators of theft, slavery, and murder while lending salience to the most reactionary elements in West German political discourse.”

At the time, McCloy’s move to placate those seeking clemency for war criminals drew a sharp rebuke from former Nuremberg Trial prosecutor and Chief Counsel Telford Taylor. Taylor wrote an op-ed in the New York Post arguing that any review of the war crimes trials would “only benefit ‘those who have wealthy and powerful influences behind them.’”

The “retreat from Nuremberg is on,” Taylor said (Endnote 2). Writing in The Nation, Taylor further wrote:

True democrats in Germany will not applaud the release of Krupp directors and S.S. concentration camp administrators. Nor will German nationalist sentiment be appeased. For the ultra-nationalists, Nuremberg has become an invaluable whipping-boy…. By these commutations we have added a powerful new weapon to the Kremlin’s propaganda arsenal, and it will not be long before we feel the sharpness of its edge and the power of its thrust.

Ultimately, though, the controversy faded away. The U.S. had engaged a new tremendous war on the Korean peninsula and was even targeting the revolutionary Chinese regime of Mao Zedong.

Preceding Ridgway, the first Commanding General of the Korean War was General Douglas MacArthur. It would take decades, but later it would be revealed that after World War II, MacArthur had been key in advocating for and obtaining a full-scale amnesty for the war criminal Shiro Ishii and his compatriots in the Japanese germ warfare division, Unit 731.

MacArthur fell afoul of President Truman after the general pushed for a full-scale war with China, including use of nuclear weapons, even to the extent of his privately lobbying allies and Congressional representatives. Truman’s replacement for MacArthur was the commanding general of the 8th Army then fighting in Korea, Matthew Ridgway.

Ridgway had a storied career during World War II, leading the 82nd division in its landing at D-Day and its march through Normandy. According to a PBS American Experience article, Ridgway was seen as a"‘kick-ass man’ who became known as ‘Tin-tits’ among his men for the hand grenades prominently strapped to his chest at all times.”

NATO’s website has a page dedicated to the general who succeeded Dwight Eisenhower as Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. The NATO biography states Ridgway “performed daring feats that became legendary down the ranks. According to military historian Thomas Fleming, during the Second World War, ‘one of his favorite stunts was to stand in the middle of a road under heavy artillery fire and urinate to demonstrate his contempt for German accuracy. Aides and fellow generals repeatedly begged him to abandon this bravado. He ignored them.’”

Only approximately six years after the end of the World War II, Ridgway was to express a very different attitude towards the German commanders.

“Orders in Korea ‘of the kind for which the German generals are sitting in prison.’”

By May 1952, Ridgway had finished his time in Korea, and been rewarded with command of Allied forces in Europe. But his stay in Korea was not without controversy.

Marine Corps Colonel Frank Schwable’s deposition to Chinese interrogators about U.S. germ warfare described the central role of Matthew Ridgway:

The general plan for bacteriological warfare in Korea was directed by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff in October, 1951. In that month the Joint Chiefs of Staff sent a directive by hand to the Commanding General, Far East Command (at that time General Ridgway), directing the initiation of bacteriological warfare in Korea on an initially small, experimental stage but in expanding proportions.

While the academic world has been incredibly slow to pick up on it, in 2010 the CIA released two dozen previously classified communications intelligence reports that quoted U.S. codebreakers transcripts of DPRK and Chinese military communications describing attacks by U.S. germ warfare weapons. These reports corroborate Schwable’s testimony, and that of two dozen other officers who described U.S. use of biological weapons to their Chinese captors. Very recent research has shown that these confessions on the use of biological weapons were not coerced, but imprisoned U.S. flyers previously had been instructed by Defense Department officials to tell what they knew to their captors, should they be captured.

Is it possible that Ridgway had germ warfare in mind when he later appealed to the High Commissioners of West Germany (representatives of the U.S., Britain, and France) for clemency of German officers convicted at war crimes tribunals? His testimony to the U.S. high commissioners came before the U.S. aerial germ war campaign had begun. More likely he was referring to the napalming or carpet bombing of cities, the strafing by machine guns of civilians and other mass executions.

“Not long after McCloy’s review decisions [in Jan. 1951], General Matthew Ridgway (SACEUR 1952–53) urged the high commissioners to pardon all German officers convicted of war crimes on the Eastern front. He himself, he noted, had recently given orders in Korea ‘of the kind for which the German generals are sitting in prison.’ His ‘honor as a soldier’ forced him to insist upon the release of these officers before he could ‘issue a single command to a German soldier of the European army.’ [Large, 1996, pg. 117, see endnote 1]

Gen. Ridgway’s comments to the High Commissioners, while pertaining to the controversy surrounding World War II Nazi war criminals, amounted to a self-condemnation of war crimes by Ridgway himself, and of U.S. conduct of the Korean War, the criminality of which has been mostly covered up by U.S. academics and the press for decades now.

A group of historians, journalists and activists have set up a website as a resource guide on U.S. foreign policy. Referencing the atrocities committed during the Korean War, they wrote about the mass executions of the “summer of terror,” whose timeline neatly matches Ridgway’s admissions:

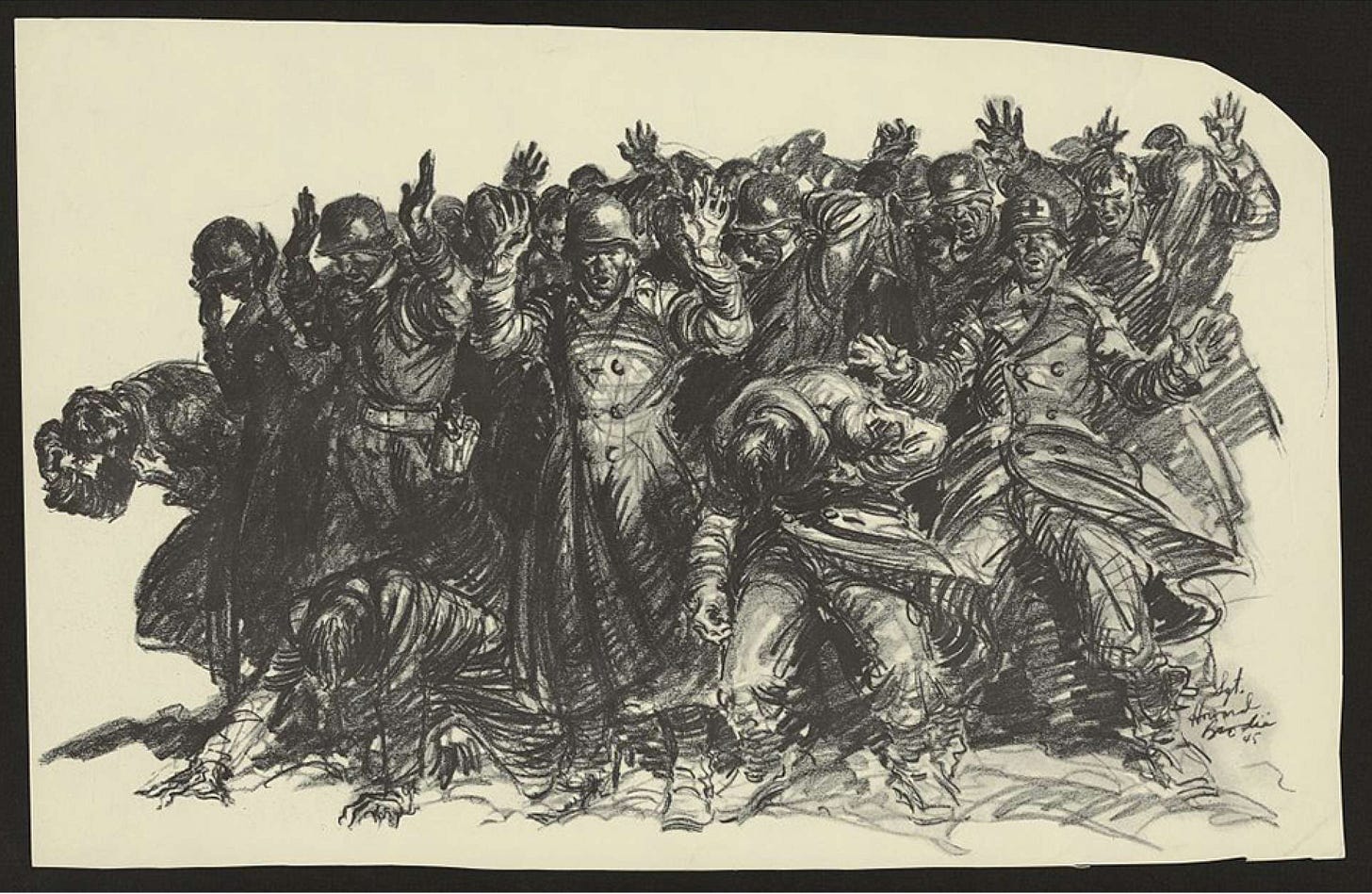

Some of the worst atrocities occurred in the summer of 1950 when South Korean KNP [Korean National Police] and ROKA [Republic of Korea Army] units emptied the prisons and shot detainees, dumping the bodies into hastily dug trenches, abandoned mines, or the sea.[212] British journalist James Cameron had encountered prisoners on their way to execution only yards from U.S. Army headquarters and five minutes from the UN Commission building in Pusan. “They were skeletons and they cringed like dogs,” he wrote. “They were manacled with chains and… compelled to crouch in the classical Oriental attitude of subjection. Sometimes they moved enough to scoop a handful of water from the black puddles around them. . . . Any deviation from [the Oriental attitude] brought a gun to their heads”….

The most concentrated killing of the war occurred in Taejon, where the KNP slaughtered thousands of leftists under American oversight. According to the historian Bruce Cumings, in July 1950, as “the North Korean People’s Army bore down upon the city of Taejon, south of Seoul,” South Korean police “authorities removed political prisoners from local jails, men and boys along with some women, massacred them, threw them into open pits, and dumped the earth back on them. Somewhere between 4,000 and 7,000 died . . . American officers stood idly by while this slaughter went on, photographing it for their records, but doing nothing to stop it.

The full scope of U.S. and ROK atrocities is still not known to this day, obfuscated by decades of censorship, political repression, and the political abasement of generations of Western and South Korean journalists.

Whatever the competency of ex-President Trump, or even his real intentions in initiating a peace process with the DPRK back in 2018, it is clear that the people of both North and South Korea definitely desire peace. The North Koreans and the Chinese, too, wish for recognition of the truth of what they suffered during the Korean War. The U.S. cannot maintain its bullying stance forever.

It is time to end the Korean War and acknowledge the crimes committed during the waging of that war. Those still alive who are culpable for these crimes should be brought to justice. Refusal to come to terms with the history of these crimes only enables current war criminals as they engage in their own crimes.

Endnotes:

“Ridgway’s remarks recorded in PA [Parlamentsarchiv], Stenographische Protokolle, Sonderausschuss zur Mitberatung des EVG-Vertrages und der damit zusammenhangenden Abmachungen 6. Sitzung, 37.” Germans to the Front: West German Rearmament in the Adenauer Era, by David Clay Large, University of North Carolina Press, 1996 (pg. 286).

While Large wrote that Ridgway’s comments were made not long after McCloy’s clemency decisions, his reference to the general as the commander of European forces makes it appear that Ridgway’s admissions were made sometime after May 1952, when the general assumed the post of Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR). But McCloy’s decisions were made in January 1951. More likely, Ridgway made his comments sometime between late 1950 and June 1951, when the unpardoned Nazi war criminals at Landsberg Prison were executed, and prior to Ridgway’s assumption of European command. Without the ability to access the relevant German document, I can’t give a precise date for Ridgway’s statement.

Quotes from Law and War: International Law and American History, Revised Edition, by Peter Maguire, Columbia University Press, 2010, pg. 166.

When I was in high school (1970’s), we were prohibited from calling it a “war.” It was always the Korean CONFLICT. I actually received a “D” on a test because I dared to use the prohibited word.

Woah, woah. First, thank you for your work, I very much enjoy reading it.

But I gotta correct you on your intro.

Trump and N Korea rapprochement wasn't stopped by ineptitude of Trump! The entire deep state, neocons, and particularly Democrats trashed him and sabotaged it!

I'm no lover of Trump (I voted for Biden, though I now regret it). But peace with N Korea was pursued by Trump and booed by the NYT, US foreign policy establishment, and Democrats!

These politicians are largely puppets. But Trump and N Korea is a unique situation where he refused to listen to Bolton and the other jackasses in his cabinet. Why do you think liberal media mocks Trump and his relationship with Kim Jung Un?

You must know from your research that everything Americans are told about N and S Korea is inverted. That S Korea is a dictatorship run by the US deep state, and N Korea (DPRK) has a government of action that fights for working families. The US hates N Korea because they don't want Americans to know that a gov organized for the needs of its people (instead of profit) is possible and that these places already exist!

Yes. A long way to go still for the DPRK. But I bet you no adult in N Korea who wants to work is unemployed. Trump is the first politician in decades to try to mend relations with N Korea. Good for him. I don’t care if he did it for narcissistic reasons. Does any American politician do anything for moral reasons? Nah. But Trump's self interest in being seen as a negotiator or peacemaker is in my self interest and your self interest and the entire world's interest.