U.S. Air Force Textbook Described How to Use Biological Weapons

Before the U.S. banned biological weapons, the U.S. Air Force taught ROTC cadets the "basic tools" of using such weapons, the better to guard "the security of the free world"

If you do the kind of research I do, you have to enjoy looking through old documents and books. Much of what is “hidden” about history isn’t necessarily suppressed or censored — though there is too much of that! What’s said to be “hidden” is sometimes what is simply forgotten, left on remainder tables, tossed out with the trash, lingering on dusty shelves of obscure bookstores, or exiled to distant Internet search pages that no one ever bothers to retrieve.

Recently I came across a 1961 copy of Fundamentals of Aerospace Weapon Systems, published by Air Force ROTC at Air University. Headquartered at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama, Air University (AU) was established in 1946, a year before the Air Force was itself established as a separate branch of the U.S. military services in 1947. According to its current website, AU’s mission is to “Access, train, educate and develop Air and Space warfighters in support of the National Defense Strategy.”

I thought it might be interesting to see what attention is given to biological weapons (BW) in this textbook, and hope readers find the content interesting as well. I’m going to go ahead and abbreviate Fundamentals of etc. as FAWS, for purposes of this article.

“The contents of this book have been compiled as a survey of present aerospace weapons systems and their use by the United States Air Force in its assigned role as guardian of the security of the free world”

The author or authors of FAWS set out the purpose of the book:

An early introduction to the elements of aerospace weapons systems will provide the Air Force ROTC cadet with an orientation to the basic tools which the United States Air Force employs as it accomplishes its mission. (pg. vi)

The authors also apologize for the fact that the nature of FAWS was such that “no information of a classified nature may be placed in a publication with such wide dissemination as this book enjoys” (Ibid.). I will return to this point at the close of this article.

While it was unlikely I would find any surprising new information about U.S. military biological warfare plans or capabilities in this book, I thought it could provide an interesting example of how during the Cold War incoming military recruits were educated about BW weapons currently in the Air Force arsenal. In other words, the text was about the normalization of mass murder by use of bacteria, viruses, protozoa, rickettsia, or plant toxins, delivered via military munitions.

The introduction to the book explains, “The contents of this book have been compiled as a survey of present aerospace weapons systems and their use by the United States Air Force in its assigned role as guardian of the security of the free world” (pg. xiii).

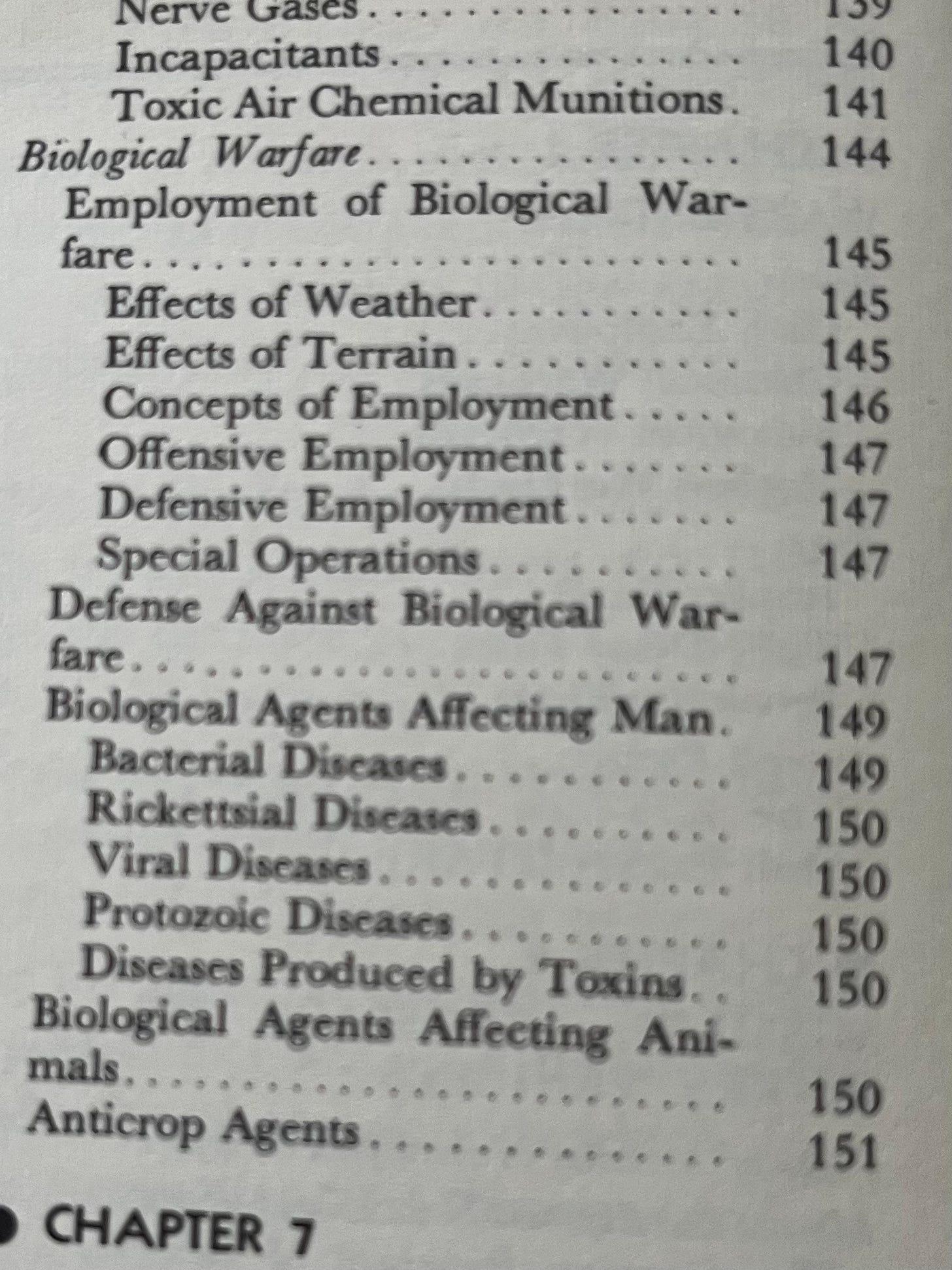

Chapter 6 of FAWS is titled “Chemical and Biological Warfare.” We will (for now) skip the section on Chemical Warfare, which included sections on incendiary weapons, smoke agents and tanks, and toxic chemical agents, such as “nerve gases” and “incapacitants.” We want to look at the subsection on “Biological Warfare,” which occupies pages 144 to 152 in the book.

The Table of Contents section on BW is shown below:

Readers interested in the discussion of BW in the text of this book, as described below, might wish to download and read the relevant sections of the 1966 Army Field Manual 3-10, “Employment of Chemical Agents.” The document has a 33 page annex, “Employment of Biological Weapons.” This document is definitely worth reading, and the parameters for its discussion, much pared down, are exactly what the FAWS textbook discusses in an attenuated, non-classified fashion. I might return to a fuller analysis of FM 3-10 at some point in the future.

Air Force Textbook Responds to Charges U.S. Used BW in Korea

The first thing that struck me in the 1961 Air University FAWS textbook was how it brought up the charges against U.S use of biological weapons in the Korean War. The passage is worth quoting in full. In reading the following, it’s helpful to remember that the charges of U.S. Air Force use of BW had been made only nine years earlier, and had led to controversy both in the press and internally within the military itself.

Biological warfare is the intentional use of living organisms, or their toxic products, to cause disease or death in man, animals, or crops. Although biological warfare is not a new idea, it is assuming greater importance in military planning because of recent scientific advancements and increased international interest. Communist charges against the United Nations, or more specifically, U.S. troops in Korea, brought biological warfare to the attention of the general public. The fact that biological warfare was not used in Korea and that the accusations were completely false has in no way lessened the interest and curiosity of both military and civilian segments of our population. (FAWS, pg. 144)

The introduction to the FAWS section on BW gives a brief summary of the history of use of biological weapons. In a nod to the scandal that would later erupt over revelations Japan used biological weapons during World War II, the book notes, “In 1940 and 1941 it was reported that plague-infected fleas were dropped on Chinese cities, but the validity of these reports has never been fully established. There were cases of plague which occurred at this time in the city of Changteh, an area in which plague is not endemic” (Ibid.).

The book, which seems to have implied that plague in Changteh might have been induced by biological weapons attack using insect (flea) vectors — without, of course, ever mentioning Japan as the culprit — then appears to pull back from its own implications about past use. The fact is, biowar and intelligence experts in the military fully knew all about Japan’s widespread use of bioweapons in China, not to mention the hideous human experiments undertaken to develop such weapons.

FAWS nevertheless published their pack of lies:

Biological warfare does not fall in the category of tried weapons. The instances of its use have been too few, too specialized, and too poorly documented. In fact, the feasibility of biological warfare as a weapon has often been questioned. (Ibid.)

Indeed, there were some even inside the military that were opposed to or questioned the efficacy of using “biological warfare as a weapon.” But that is a subject for another time.

Despite the supposed lack of experience with such weaponry, FAWS assured its ROTC readers that, nevertheless, “as a result of field trials under various conditions, much has been learned in recent years about the effectiveness of diseases disseminated in an aerosol cloud. There is no longer any doubt that very large areas could be covered with agents which would infect large percentages of the target population. The techniques for mass production of these agents are known” (Ibid.).

According to FAWS, the effect of BW use includes both death and incapacitating illnesses. The latter “would tax medical and economic facilities more severely than would a large number of fatalities.” Meanwhile, BW attacks on animals or crops would be aimed mostly at “death and destruction.” (Ibid.)

There’s one other angle, as well: “In all forms of biological warfare a psychological reaction could be expected, and every effort would be made to exploit it.” (Ibid.)

The rest of the section appears dedicated to defenses against BW, as well as a discussion of “the military requirements” of such BW agents, including the “capability of infecting a host, economical production in adequate quantities, and stability in storage. Other desirable properties are difficulty of detection, capability of producing rapid and widespread disease, difficulty of protection and immunization, entrance through more than one portal, and a short incubation period” (pg. 145).

All in all, a fairly chilling, and straightforward, introduction to the subject, minus the lying about past use, of course.

Air Force Teaches How to “Employ” Biological Warfare

The FAWS textbook next gets into the nitty-gritty of actually using biological weapons. The emphasis is not on doctrine, but on operational variables important to BW usage.

The FAWS authors remind the reader, “The availability of biological agents that can produce death or varying degrees of incapacitation among target personnel permits the commander to select an agent that will produce the desired military effect” (pg. 145).

This sounds like the decision to use operational BW use rests in the hands of local commanders. Such was the mechanism for deployment approved for use of anti-crop BW agents, as I ferreted out and reported on in a little-noticed article a few years back.

FAWS instructs its readers that there are things commanders must consider when using BW. These include the incubation period of different biological agents (usually “several days”); the effects of weather, particularly of BW distributed via “moving clouds” [aerosol delivery - JK], including windspeed, amount of sunlight, and the effects of terrain.

Two important factors in the choice of biological agents was not discussed by FAWS, but you can find them mentioned in Army Field Manual 3-10 cited above. These are “pathogenicity,” or the ability or strength whereby an organism or pathogen can cause a disease; and “virulence,” or how effective an agent can overcome a body’s defenses and fully infect someone. I guess FAWS editors found that too grisly a subject for young cadets.

Regarding terrain, FAWS authorities insisted, “Ground contamination following a biological aerosol attack is not generally considered a hazard to troops traversing or occupying the terrain.” Yet “a few casualties may be produced by secondary aerosols that are formed by marching men and vehicular traffic” (pg. 145-46). Too bad, I suppose, for those so exposed. But then, “friendly fire” has always a part of warfare, or so the military mind supposes.

How does one “employ” biological agents? FAWS described two primary methods: “on-target and off-target attacks.”

In an on-target attack the biological agent is released directly on the target area…. Since the agent is distributed more or less uniformly over the target area, wind direction and velocity are not critical factors. (pg. 146)

An off-target attack is one where BW “is released at a substantial distance upwind.” It is the wind that then spreads the biological agents over the intended target or targets. This “requires the release of the agent in such a pattern that a wind direction anywhere within a 45º sector will effectively carry the wind over the target area.” (Ibid.)

But what about making the choice of biological agent? FAWS provided two handy charts that simplified the decision process of selection of both bioagent and its munition. Note: for purposes of the charts reproduced below, a “line source” weapon is one that “produces an aerosol in a line and relies on the wind to carry the agent over the target.” A weapon that scatters BW “at random over the target area” is described as “self-dispersing.” (pg. 146)

By the way, FAWS doesn't mention specific biological munitions by name, but the M33 biological cluster bomb, pictured below, would be an example of a “self-dispersing” biological weapon. According to a U.S. Army history, it “was the first biological weapon standardized by the U.S. military” (pg. 51). According to Matthew Aid’s introduction to Brill’s “Weapons of Mass Destruction” document collection, both the M114 and the M115, aka E73, feather bomb (another self-disperser), were “ready for production” by “the end of September 1951.”

The FAWS charts also use the terms “decay rate,” and differentiate between “lethal” and “incapactating” bio-agents. Brucella, mentioned above, would be considered an incapacitating weapon, since while it produced illness that can last weeks or months, it does not generally kill. Anthrax would be an example of a lethal weapon. Anthrax is also an example of a low decay rate agent. It stays in the environment practically forever. Botulinum as a weapon, on the other hand, has a high decay rate. It dissipates quickly in the environment.

Chart One:

Target Characteristic —> Characteristic of the “Effective Agent”

Close to friendly forces —> High decay rate

Large area target —> Low decay rate

Primarily military target —> Lethal

High percentage of friendly civilians —> Incapacitating

Chart Two:

Target Characteristic —> Characteristic of “Effective Munition”

Large areas —> Self-dispersing

Poor biological-chemical warfare discipline

or inadequate alert system —> Self-dispersing

Wind direction unknown —> Line source

Wind direction known (within 45º) —> Line source

Off-target attack preferred or required —> Line source

Small area —> Line source

There is only a brief paragraph specifically on the issue of “offensive employment” of biological weapons. It is worth reproducing in full:

“Enemy targets in the vicinity of the line of contact will not normally be engaged with biological agents because of the delay in producing casualties. Biological agents may be employed, in support of offensive operations, on relatively deep targets such as Army reserves and airbases within an enemy country where a delay in casualty effects will be acceptable.” (pg. 147)

There is a page or so about defense against biological weapons attack. As interesting as that may be — and it mostly boils down to use of both immunization and employment of protective gear — I’m going to skip it in this account, as my emphasis is on how the U.S. considered use of biological weapons from either an offensive or “special operations” standpoint.

Special Use of Biological Weapons in Cold Climates

In the FAWS section on use of BW in “Special Operations,” the reader is informed, “Decay of biological agents is not as rapid in arctic areas as in temperate or tropical areas” (pg. 147). This is highly relevant to the controversy over whether the U.S. used biological weapons during the Korean War. Opponents of the China-DPRK charges of U.S. use of BW in 1952 have repeatedly claimed (pg. 6-14) that the cold winter weather in Korea, where biological bombing of both North Korean and China was first alleged, argued against the use of insect-borne biological weapons by the Americans.

Winter was, according to U.S. Cold War “scholar,” Milton Leitenberg, “the wrong season for anyone to attempt insect-borne BW” (Ibid.).

As I wrote in an article for The Canada Files last year:

Biological warfare researchers in the West, as well as in Japan, were interested in how their bioweapons would work in wintry conditions. This was important as from the standpoint of these countries, the Soviet Union, with its vast tracts of frigid countryside, was thought of as their most likely target.

Shiro Ishii, the leader of Unit 731, Japan’s World War Two biological warfare unit, was, according to General MacArthur’s office in postwar Tokyo, an expert on “the use of BW in cold climates.” Ishii’s specialty was use of insect vectors in biological bombs. This specialty was used by MacArthur and scientists from the U.S. Army Chemical Corps at Camp Detrick, to help validate the usefulness of Ishii and his associates to military and political leaders back in Washington D.C. The latter were considering a bargain to provide amnesty for war crimes to Japanese bio-researchers, in trade for what they had discovered in their very active germ warfare program.

Along similar lines, a U.S. Chemical Corps report on its research and development division in autumn 1951 specifically mentioned work on “cold weather agents.”

In fact, there is plenty of evidence regarding the use of insect vectors in cold winter environments in the literature on Unit 731. In his famous book, Factories of Death, (2002, p. 104), historian Sheldon Harris described how Japan’s Unit 731 conducted field trials on plague using fleas in Jilin Province in China during the winter of 1942, killing 300 people and making hundreds more ill.

There is also an admission from Major General Marshall Stubbs, the Chief of the Army Chemical Corps, who told the House Committee on Appropriations on March 26, 1962:

“In other areas of the [U.S. Army Biological Laboratories, i.e., Chemical Corps] program the genetics of insects and plants are being investigated. Mutants of insects species are examined for increased resistance to insecticides and cold temperatures. Genetics of population changes, gene competition, radiation effects on survival, and propagation of insects and development of desired characteristics are studied intensively.” (Italics added for emphasis, page 177)

For more information on biological weapons and cold weather, see my January 2024 article on the subject.

Characteristics of Biological Agents

The FAWS chapter on Biological weapons concludes with a summary on the various biological agents employed against both human beings, animals, and enemy crops.

Bioagents can be found in diseases “caused by bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and toxins of microbe, vegetable, or animal origin.” Examples of bacterial diseases of interest are “anthrax, undulant fever [Brucellosis], tularemia [Rabbit Fever], and melioidosis” [Whitmore’s Disease]” (pg. 149).

Some of these diseases, such as tularemia, can be transmitted via “bites of infected flies and ticks” (pg. 149). Such insect vector attack is described as an “indirect attack” in the FAWS text.

Rickettsial organisms produce diseases “which might be adaptable for biological warfare,” such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Q-Fever.

Viral diseases of interest include smallpox, yellow fever, and encephalitis and encephalomyelitis. These diseases have, of course, killed millions of people throughout human history. The FAWS authors informed their ROTC trainees that “Smallpox is effectively combated by vaccination, but revaccination every 3 years is advisable to maintain minimal immunity” (pg. 150).

This reminder regarding smallpox vaccination is important only if one either fears smallpox attack, or is considering use of smallpox agent and is concerned about potential blowback on troops or friendly populations (“reactivity” in BW lingo).

The fact is the military was very interested in use of smallpox as a weapon. Its work on the deadly bioagent was discussed with the FBI at a meeting at Dugway Proving Ground in November 1950. North Korean accusations that the U.S. was using smallpox as early as 1951 have long been denied by U.S. authorities. I’m going to revisit that aspect of the U.S. BW scandal during the Korean War in an upcoming article soon.

But for the purposes of this article, it’s worth recalling that at this November 1950 briefing, the Chemical Corps official at Dugway told the FBI “that through selective culture smallpox strains have been developed against which immunization by vaccination is not effective.” In other words, smallpox had been weaponized.

The FAWS text next lists BW agents produced by protozoa, including “amoebic dysentery, African sleeping sickness, and malaria.” The Air Force notes, “this type of disease is the least likely to be used in biological warfare due to difficulty of production and transmission of it” (pg. 150).

Finally we have the diseases produced by plant, animal or microbial toxins. The most important of these was botulism, produced by the bacteria Botulinum. The U.S. BW program was very interested in producing weapons that could spread botulism. For years the U.S. worked with the UK and Canada in a tripartite agreement to split up in a division of labor fashion the work these allied nations were doing on biological warfare.

In 1947, top Canadian scientist Guilford Reed reported to Canada’s Defense Research Board BW Research Panel on the Botulinum project:

“Methods have been developed, through pilot plant stage, for the productions of types A and B [botulinum] toxin in semi-purified form… it has a long storage life… Satisfactory air-borne clouds of [botulinum] toxin have been produced in the laboratory and fairly extensive field trials have been carried out with the toxin dispersed from small aircraft bombs.”

The FAWS chapter concludes with a short list of BW agents used against animals and plants. Anti-animal agents, meant to attack enemy food supply or use of draft animals, included “foot-and-mouth disease, rinderpest, hog cholera, and fowl plague” (pg. 150). Anti-crop agents, meant to mainly impact food supply for both animals and man, included “late blight of potatoes, stem rust of cereals, and blast of rice” (pg. 151). In fact, by 1951, and not mentioned, of course, by FAWS, the U.S. had already forward positioned in England and Libya anticrop weapons for potential use against the Soviet Union.

“Non-living anticrop agents” are also listed in the FAWS text, “such chemicals as 2,4-D (2,4-dicholorophenoxyacetic acid) used against broad-leaved plants such as cotton, beans, sugar beets, sweet potatoes, flax, Irish potatoes, and soybeans.” 2,4-D was one of the constituents of Agent Orange defoliating toxin that was dumped in the millions of gallons by the U.S. on South Vietnam.

What’s to be learned from this foray into an old Air Force textbook? I believe it’s worth looking back at this old material because it demonstrates how use of deadly weapons of mass destruction was normalized and presented to military recruits.

Repeatedly, BW weapons and organisms are referred to conditionally, as to how they “might” be used. In fact, as I believe I have shown, these biological agents had already been extensively studied and weaponized.

It’s not that the FAWS text wished to minimize the work done, or mislead new recruits. I think the authors had to contend with the fact that these weapons were classified, and could not be directly discussed. Even more, some of these weapons, and ones that still remain classified because they were utilized in cooperation with former Unit 731 personnel in the germ warfare attack on Korea and China in 1952-53, had not just been “developed.” They had been used.

I imagine readers may have their own take on this material, and please feel free to leave your thoughts or feelings in the comment section below. Meanwhile, if you made it to the end of this essay, you are hereby rewarded with an A in BW class. Thanks for your participation!