USAF Airman: "The Truth About How American Imperialism Launched Germ Warfare"

A WW2 USAF vet flying in the Korean War was part of an air crew dropping biological bombs over Korea. Captured, he confessed, later retracted his confession, then changed his story again decades later

There is no full history of the published claims of 25 U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps airmen that the U.S. used biological weapons (BW) in the Korean War. I have already in the past provided an overview of some of the major confessions from senior captured officers. But the initial confessions, both written and via radio broadcast, of Air Force personnel detailing their experience of U.S. use of germ warfare came from lower ranking pilots and navigators. These confessions were widely reported in the world press in the spring and summer of 1952.

The 25 full “confessions” in print (see here, here, and here — the latter two links consisting of rough scans from original PRC publications) are only a subset of what must be more such confessions, as some 36 Air Force confessions in total were made in either film, radio, or print form. (See pg. 274 at link.) That means nearly a dozen confessions remain unreleased or unavailable for some reason.

In February 2021, a digital book was published that contained transcriptions of all the available flyer confessions (though I have not checked to see how their accuracy compares with the originals). The main point I wish to make here, however, is that for the most part, for several decades after the end of the Korean War, the bulk of the BW confessions by U.S. military personnel remained unavailable in the United States.

I’ve decided to present below the documentary case history of one of the confessing officers, Lt. Kenneth L. Enoch. I chose Enoch because he was uniquely someone for whom we have his initial written confession; a transcript of an interview he had with members of the International Scientific Commission (ISC) which visited China and North Korea in July-August 1952; his later September 1953 retraction, upon repatriation, of his germ warfare charges; and an even later 2010 partial retraction of his retraction, if you will, wherein he told documentarian Tim Tate, working then for Al Jazeera, that contrary to his 1953 statement, he had not been ill-treated by his Chinese captors.

Enoch also told Tate that biological warfare “specialists and evil doctors” had sent flyers into combat with bacteriological weapons.

I am going to present all the evidence concerning the Enoch case here for both my readership and interested scholars. I believe that altogether these documents present a unique example of the evidentiary material I’ve gathered surrounding the flyers’ confessions and their subsequent retractions. The ISC interview, in particular, includes biographical information about Enoch’s life that has not been revealed until now, e.g. that he had been a steel worker, or that during World War II he had been stationed in China.

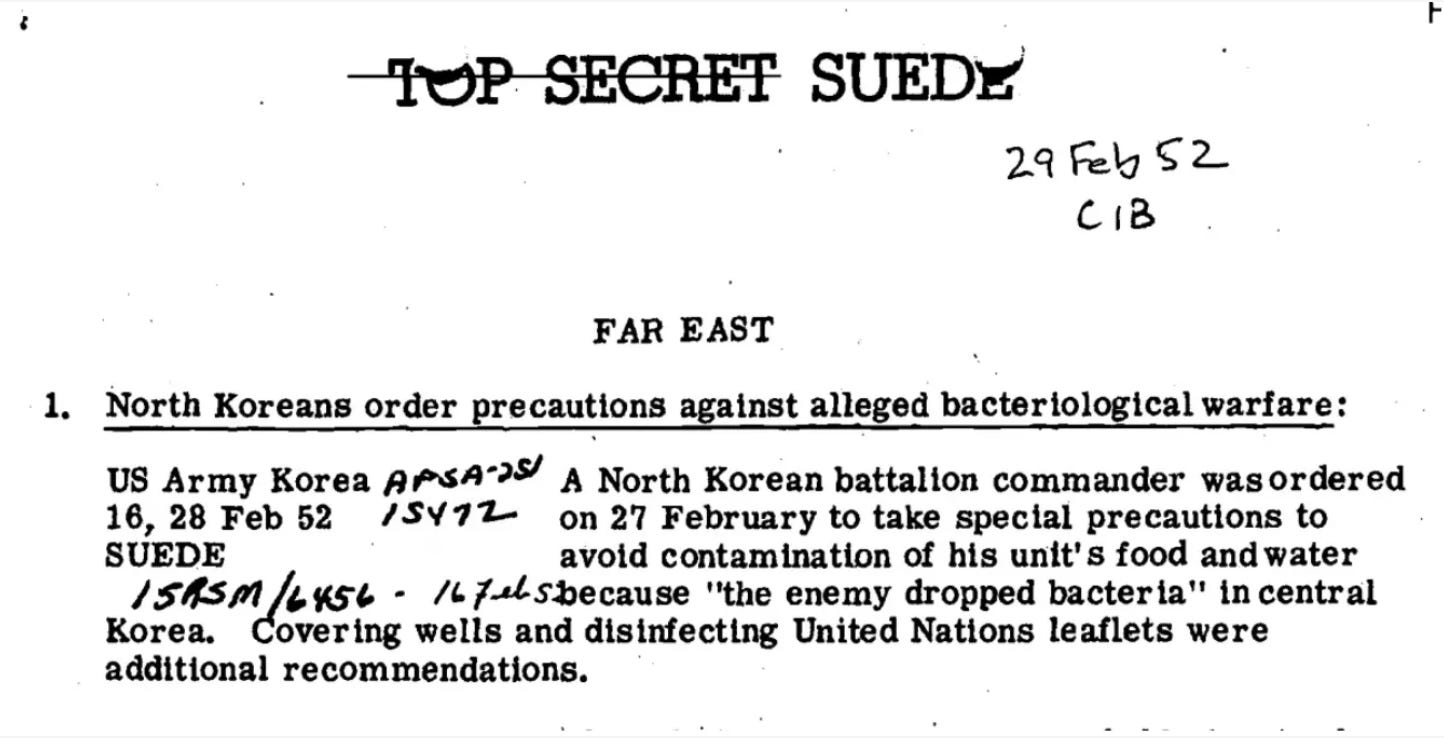

Of course, this evidence cannot be fully appreciated without reference to other documentary material. In particular, I want to reference here the two dozen or so CIA communications intelligence reports the Agency declassified in 2010 that quote decrypted military intercepts of Korean People’s Army and Chinese Volunteer Forces’ messages in real time about being attacked by U.S. biological weapons.

Also of interpretive significance in relation to Enoch’s confession and retraction is the fact that despite U.S. government contentions about Communist use of torture or “brainwashing” to obtain U.S. airmen’s germ war confessions, the Pentagon had instructed officers that if captured they could, using their discretion, freely discuss the germ war program with their captors! This surprising policy towards the airmen was revealed during a punitive 1954 Marine Corps official inquiry into the BW confession of Colonel Frank Schwable. The history of that remarkable (and suppressed or forgotten) revelation is discussed in this linked article, which is based on the official findings of the Schwable Board of Inquiry and various contemporary news reports.

The Pentagon’s decision to protect its highly valued Air Force and Marine Corps human assets from undue damage was at least in part due to what they feared could be coercive interrogations. Such a lenient policy for men at high risk of capture was not exceptional by any means, as the article linked above explains. In addition, the Pentagon’s expanded policy regarding Code of Conduct prisoner behavior in captivity, which was granted only to U.S. airmen and not rank-and-file Army, Navy, or Marine Corps ground or sea personnel, helps us understand why more punitive actions against the BW confessors was not taken.

There is also the fact that before any BW confessions by Kenneth Enoch or any other airmen were ever made, according to government consultant Albert Biderman in 1951 the research branch of the Air Force’s Psychological Warfare Division at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama had constructed “an elaborate laboratory facility at Maxwell to test theories regarding the manner in which such [false] confessions were extorted, with the aim of providing flyers with means of resistance. The unit was anticipating the extortion of false confessions by the Communists in Korea and the prospective exploitation of prisoners for intelligence purposes” (A. Biderman, March to Calumny: The Story of American POWs in the Korean War, The Macmillan Company, 1963, pg. 274, bold added for emphasis.)

As I wrote in an article for Counterpunch in November 2021, “One wonders how they received funds to build a laboratory to test theories about false confessions, when no such confessions had as yet occurred. It seems just as reasonable, if not more so, to think that they expected statements about germ warfare to leak out, because in fact the U.S. was involved in biological warfare, and other wartime atrocities, and any statement to that effect would be political dynamite. Indeed the statements made were explosive when they finally surfaced in the world press.” (See the reprint of this same article here at Hidden Histories.)

Lt. Kenneth L. Enoch was a U.S. airman-navigator during the Korean War. Captured by North Korean-Chinese forces, he was one of approximately two dozen U.S. airmen to confess to using germ or bacteriological warfare on North Korean or Chinese forces or civilians during the Korean War. His confession was written out in longhand and dated April 1, 7 or 9, 1952. (The date one accepts depends on how you read his handwriting. I'm not sure which date it is from the copy I have.) According to this post online, Kenneth Lloyd Enoch died at age 88, on November 6, 2013, in Cypress, Texas.

In July 1952, China Monthly Review published a contemporaneous article on Enoch's confession, and that of a U.S. pilot, John Quinn, "Captured US Airmen Admit Germ Warfare." In the United States, the news of the confessions exploded in the headlines on May 5, 1952.

It wasn't long before the story as reported in the U.S. emphasized the idea that the confessions had been coerced. See this October 23, 1952 Associated Press article, "2 Fliers 'Forced' into Confession." It is interesting to see the word "forced" placed in quotation marks.

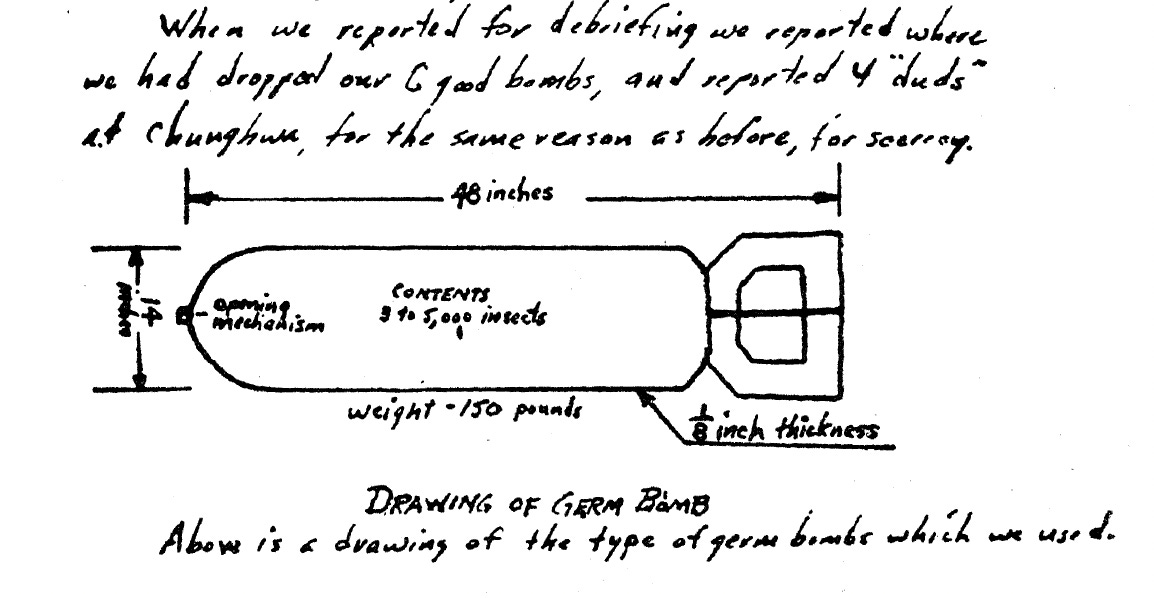

I've transcribed the copy I have of Enoch’s written confession from the full report, with appendices, of The International Scientific Commission Report on Bacterial Warfare during the Korean War. Enoch's confession occupies pages 493-500. I have tried to reliably and truthfully reproduce his written record, including crossed-out material. A drawing Enoch made, and a small portion of the reproduced confession is included in accompanying photos. I have not tried to correct spelling or punctuation, but I have added extra line breaks to delineate paragraphs, which enhances online readability. The paragraph breaks themselves follow Enoch. Any editorial comment by me is placed in square brackets.

I will save for the end of this article some brief impressions about Enoch’s confession, as well as the other confessions given by U.S. POWs during the Korean War. I have written more extensively about the (in)famous confessions of U.S. airmen in relation to germ warfare elsewhere. It is enough to say here that while reference is often made by U.S. historians and journalists about the "brainwashing" of these airmen during their Korean War captivity, the actual documentary material related to their confessions was for many decades all but unobtainable.

While I feel at this point quite confident about the general outlines of the U.S. biowarfare campaign during the Korean War, the extensive presentation of the documentary material I’ve gathered here lets readers and historians discover what is true or false for themselves.

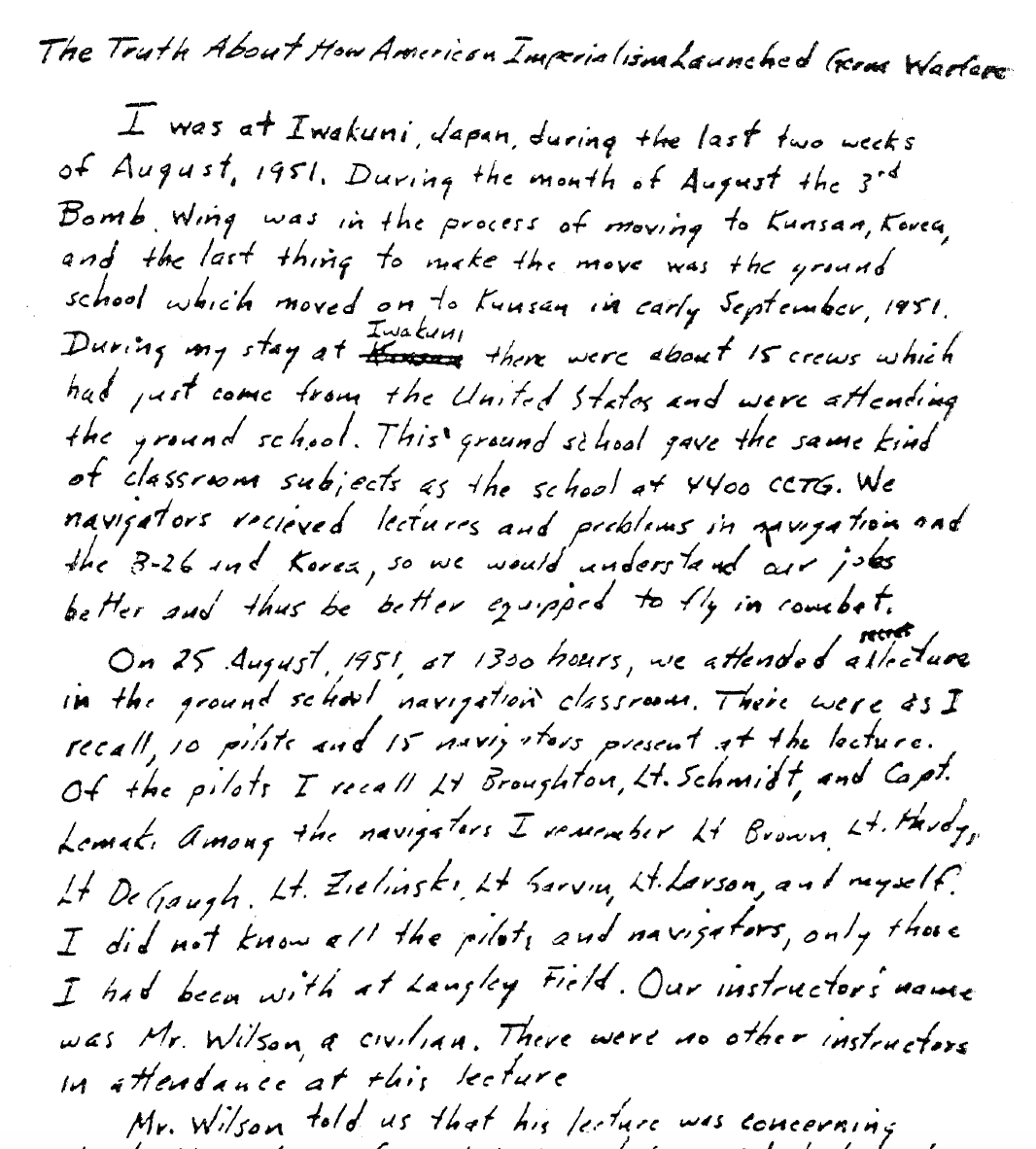

The Transcribed Text of Lt. Enoch’s Confession

The Truth About How American Imperialism Launched Germ Warfare

I was at Iwakuni, Japan, during the last two weeks of August, 1951. During the month of August the 3rd Bomb Wing was in the process of moving to Kunsan, Korea, and the last thing to make the move was the ground school which moved on to Kunsan in early September, 1951. During my stay at

KunsanIwakuni there were about 15 crews which had just come from the Unites States and were attending the ground school. This gound school gave the same kind of classroom subjects as the school at 4400 CCTG.[1] We navigators recieved [sic] lectures and problems in navigations and the B-26 and Korea, so we would understand our jobs better and thus be better equipped to fly in combat.

On 25 August 1951, at 1300 hours, we attended a secret lecture in the ground school navigation classroom. There were as I recall, 10 pilots and 15 navigators present at the lecture. Of the pilots I recall Lt. Broughton, Lt. Schmidt, and Capt. Lema. Among the navigators I remember Lt. Brown, Lt. Hardy, Lt. De Gough, Lt. Zielinski, Lt. Garvin [or Sarvin?], Lt. Larson, and myself. I did not know all the pilots and navigators, only these I had been with at Langley Field. Our instructor's name was Mr. Wilson, a civilian. There were no other instructors in attendance at this lecture.

Mr. Wilson told us that his lecture was concerning bacteriological warfare. He told us that our side had no plans at that time of using bacteriological warfare, but never-the less we might at some time, and thus the lecture was secret information and we were not to divulge its contents to anyone,areor even talk about it among ourselves.

The main part of Mr. Wilson's lecture was devoted to the weapons of bacteriologicalweaponswarfare. He did not have any examples with him, but he discussed the various methods of scattering germs, either by scattering the germs by themselves or by dropping insects and animals to spread the germs. The contents of Mr. Wilson's lecture is as follows:

The ways of dropping the germs by themselves are: 1) by dropping a bomb full of dust and germs mixed together, which will open in the air and spread the germ-laden dust with the wind; 2) by dropping dust directly from the airplane itself, by means of a spraying device, so that there will be germs in the air wherever the dust is sprayed; 3) or by dropping a container full of germ dust, either a bomb which will open in the water or a paperboard box wish will be opened by the water, into reservoirs and lakes where the people and animals use the water, and where insects will pick up the germs and spread them.

The ways of dropping insects are : 1) by dropping a germ bomb which looks just like an ordinary bomb, but is filled with germ-laden insects, and which will open on contact with the ground to release those insects; 2) by dropping insects in paperboard containers which will break open on contact with the ground, releasing the insects with their germs; 3) or by spreading insects with animals.

The ways of releasing germs by animals are: 1) To release the rats orrabittsrabbits or small game by a parachute container which will release the animals upon contact with the ground, and these animals are covered with germ-bearing lice and fleas; 2) or by releasing such animals from a boat behind the enemy shore line.

There are other ways of spreading germs also: 1) By dropping leaflets toilet paper, envelopes, and paper materials which have been covered with germs, 2) by dropping germ-filled soap or clothing; 3) by dropping fountain pens filled with germ-laden ink; 3) or by dropping infected food to the enemy troops.

You can also spread germs by howitzer or mortar shells, but since it is so close to the front it is not safe to do so.

There are many types of germs that can be spread. In addition to many weird and unusual germs, the germs of more well-known diseases, such as typhus, typhoid, cholera, dysentery, bubonic plague, smallpox, malaria, and yellow fever, may be employed. There are many types of insects to carry those germs, the most popular being the louse, flea, fly, and mosquito. The louse can carry typhus, cholera, smallpox, plague, and dysentery, as can the flea and the fly. The mosquito can carry malaria, and yellow fever.

The best way to defend against germ warfare is to be prepared. All possible people should be inoculated against all diseases possible. If insects are dropped, it is advisable to pour kerosene or oil on the containers they are dropped in and set fire to them. If they have already escaped from the containers, it is best to spray DDT over the area, preferable from an airplane. In case germ-laden dust is employed, DDT spray must be used. All exposed food must be disposed of. All exposed clothing and articles must be washed with hot water and strong soap. All water must be boiled. All food eaten must be thoroughly cooked. You must use some protection over your nose and moth to breathe, and you must, when everything else is done, change clothes and take a good bath. All trash and waste exposed to germs must be burned. Screens should be placed on all windows in the summer for insect protection. In all cases, small animals such as rats, should be destroyed so the danger of plague, which they spread with their fleas, will be lessened. If paper objects or other such items are dropped, they should be burned at once.

All weapons of bacteriological warfare are of such a nature that they should, when employed, be dropped from as low an altitude and [illegible word] on an airspeed as possible, to avoid harm to the insects If parachute-type weapons are used any altitude will suffice but it should be sufficiently low, say 1000 feet, so that the parachute will not drift from the target area

When Mr. Wilson had finished his lecture it was 3 o'clock (1500 hours) and he reminded us not to discuss the weapons subject to anyone and took his leave. This was the only such lecture we ever received. On September 1st, 1951, I went to Kunsan.

In October, 1951, and again in December, 1951, a one-hour lecture was given at Kunsan by a Major [two illegible letters]onning [could be "Fronning"] on protection against germ warfare. This lecture he have many times on each occasion, and every person was required to attend one hours lecture. He gave the same lecture in December as in October. The idea, of course, is that due to the rotation plan there are always new troops, and it is also good to keep in mind the contents of his lecture. He told us that it was not unreasonable to expect bacteriological warfare to used against us by the enemy. If they did, germ dust or germ-[illegible crossed out word]laden insectes would be used, and he stressed that we should keep our shot records, or inoculations, current and up-to-date, and also discoursed on the other pertinent data as I have discussed in the second paragraph on page 3 of this paper. [Lt. Enoch is referring to the paragraph above that begins "The best way to defend against germ warfare..."]

On the 1st of January, 1952, we were told by the operations section group briefing officer at our regular briefing to be sure and report all our duds and where they fell. This was a usual procedure and just seemed to be a casual reminder at this time. The reminder was given to all the crews it [?] the briefing by Capt. Farey, one group briefing officir [sic], Dr. [illegible] a head cold I did not [three illegible words] night, but was replaced by another navigator.

My next scheduled flight was on the night of 6 January, 1952. We were scheduled to fly on Green 8 route (between Pyongyang and Sarinon [?]), and our take-off was scheduled for 0300. The crew was Capt. Amos, pilot, myself, navigator, and Sgt. Tracy, gunner. As ususal Capt. Amos and I reported to the group briefing room and group operations office at 0200 an hour before take-off. There we always checked for the latest weather and information on the mission to be flown. On this night we were informed by the officer on duty, a captain I am not familiar with, that we were to fly to the town of Hwangjn and drop our outboard wing bombs(of which there were two) and then to drop the rest of our load as quickly as possible and come directly back to Kunsan. He told us to drop at Hwangjn at 500 feet of altitude and 200 miles per hour maximum airspeed. We called his attention to the low altitude, as were to carry 10 - 500 pound bombs according to briefing, but he told us that this was top secret and these were germ bombs, and to tell no one whatsoever about our mission. He told us that the wing bombs were already loaded and checked for us, and not to bother them, and when we returned to report them as "duds". We went over to squadron operations and met our gunner, who did not report to group, and , as far as I know, did not know of our special mission. Wehn we got out to the plane a guard was standing there from armament section. He told us the wing bombs were already checked, which we already knew. I checked the bombs in the bomb bay, 6 of them, and they were 6 regular 500-pound bombs. We took off at 0300 and flew to Hwangjn dropping our two germ bombs just outside the west edge of town. There were no explosions or any unusual things to be seen. Then we continued for two minutes to the north and dropped our eight live bombs on the highway 5 miles north of Hwangjn, and went directly back to Kunsan. We took off at 0300, our bombs were dropped at 0400, and we landed at Kunsan at 0500. This was the first time I ever heard of anyone dropping germ bombs, and we kept it a secret. These germ bombs looked exactly like a regular 500-pound bomb to me. In the day time they may have some distinguishing characteristics, but it was dark when I saw them. I did not load these bombs or see them loaded but there was no special equipment on the wings, so they are loaded in the same way as ordinary bombs.

When we reported to group intelligence for debriefing after this mission we reported two bombs [inserted] (as a matter of fact, 150 pounds)[close insertion - see drawing of bomb below, which indicated weight as 150 pounds] 500 pounds dropped at Hwangjn and reported them as "duds", and reported where we dropped our eight good bombs. The bombs are evidently reported as "duds" to keep too many people from knowing the purpose of the mission, but higher headquarters can check the reports and know where the germs were dropped.

On the 10th of January, whether by accident or design I do not know, I was again scheduled for the same mission with Amos and Tracy. This time Amos and I reported to group operations, and we were told that all 4 of our wing bombs were to be germ bombs. This time our target was to be the town of Chunghwa, on Green 8, and we were then to get rid of the rest of our bombs as quickly as possible and return to base. We were still to keep our operation a secret and report our germ bombs as "duds". Our maximum airspeed was to be 200 miles per hour and our altitude 500 feet for the germ bombs. Once again armament was to have the wing bombs checked for us. We picked up Tracy at squadron operations and went out to the plane. Once again the wing bombs looked like regular bombs. An armament man told me that we were not to bother the wing bombs, as they were all set to go.

I checked the regular bombs in the bomb bay. At 0300 we took off and flew directly to Chunghwa, dropping our 4 germ bombs at 0410 hours, at an altitude of 50 - feet and an airspeed of 190 miles per hour, on the western edge of Chunghwa. We proceeded south and dropped our regular bombs on the highway north of Hwangjn and returned to Kunsan base, landing at 0515.

When we reported for debriefing we reported where we had dropped our 6 good bombs, and reported 4 "duds" at Chunghwa for the same reason as before, for secrecy.

As I see it, the germ bombs come from a medical supply source, such as the same type which manufactures the vaccine used to combat disease, and I believe this source is in Japan, either on Honshua or Kyushu Island.

If the type of germ bomb which we dropped is used, it will open on contact with the ground, exposing the germs and insects to the open air. If it is cold outside, the insects will be dormant and sluggish, but the sun will cause them, by its heat to become active.

The leaflets are dropped in North Korea by B-29s. These leaflets are dropped in boxes which open in the air scattering the leaflets over a wide area These leaflets can be used in bacteriological warfare.

When the germ bombs are dropped, they are released by the pilot. The navigator takes notes on when and where they are dropped, and how many germ bombs. The bombs are released by pushing a button, which releases the bombs by electricity.

After the mission when the crew reports to group intelligence for debriefing, the whole crew attends the debriefing, and the report is given by the pilot and navigator. It is an informal report, and the whole crew sits around a table and give [sic] their report to an enlisted man from the intelligence section, who takes the report and puts it on paper, which he turns in to his superior. This is why the germ bombs are reported as "duds", to keep unauthorized personnel in intelligence and on the crew from knowing the secret of the mission.

To the best of my knowledge, B-26 aircraft are the only ones dropping the regular germ bomb, which looks like a regular bomb. However, the B-26 is unsuitable for dropping the other types of weapons. The leaflets are dropped by B-29's and cargo type, C-47 and C-46 aircraft, but mainly by B-29's. The cargo type aircraft are the best suited for dropping all other types of germ weapons, such as cardboard boxes, parachute containers, and articles of clothing, food, soap, and paper and fountain pens, but the B-29 can be used for these weapons also.

As to when we first started to use germ bombs, it was about the first of the year, around January 1952, I should say, since that is when we were all reminded to look for "dud" bombs. It is probable that other outfits, such as the 452nd Wing, started to use germ warfare at the same time.

The decision to use germ bombs, of course, is top secret, but due to the serious nature of this decision it undoubtedly rests with a very high command, probably the Far East headquarters in Tokyo.

Kenneth L. Enoch

9 [or 7?] April 1952

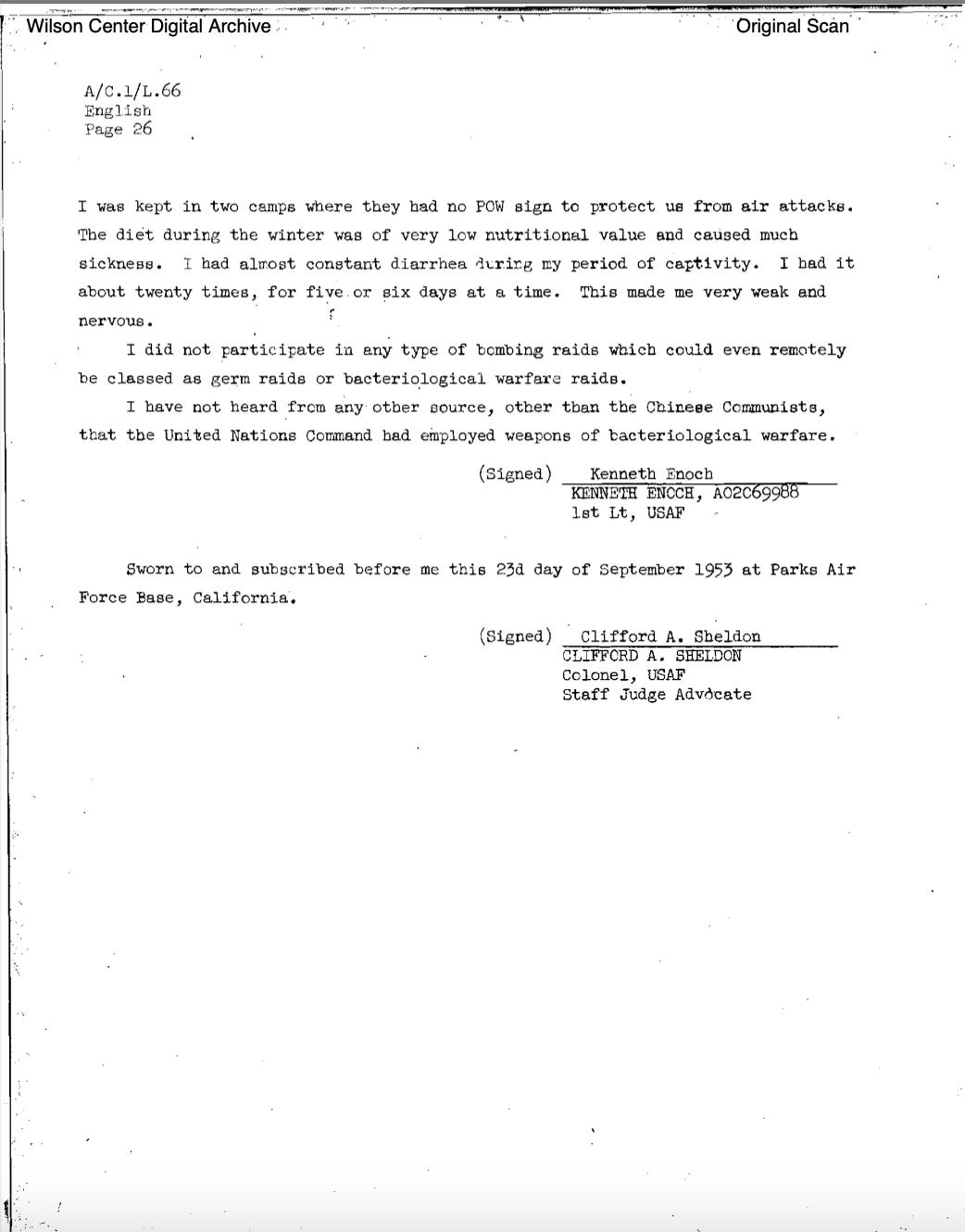

The following is a screenshot of a digital reproduction of Lt. Enoch’s statement retracting his April 1952 statement (“confession”) regarding his involvement in and knowledge of the U.S. biological warfare campaign during the Korean War. Lt. Enoch never mentions that the statement below, like all of those given by returning airmen, was made under threat of prosecution for treason.

Enoch’s retraction was recorded at Parks Air Force Base in Dublin, California. Parks was notable for being one of a handful of Air Force bases that did not have any runway. Evidently air crew action was not its primary function.

In all, only six affidavits of retraction, out of an approximate 25 depositions or confessions made by Air Force and Marine officers and printed by China’s government, were published or distributed by U.S. officials. All of the retractions, along with some statements of other POWs who putatively claimed they were tortured (without success) to make “false” confessions about the use of germ weapons, can be read in the Annexes to the Eighth Session of the United Nations, September 15 - December 9, 1953. Don’t worry. You won’t have to look that one up. I’ve linked to a PDF copy here. Lt. Enoch’s retraction is on PDF page 136.

The retractions of Enoch and the other flyers have also been posted at the Wilson Center’s Digital Archive. The Wilson Center reproduced a package of materials that State Department Legal Counsel Willard Cowles sent to UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold on December 23, 1954. The latter materials primarily concerned the January 1953 shoot-down and capture of Colonel John K. Arnold.

Arnold was Commander of the 581st Wing of the U.S. Air Force’s Air Resupply and Communications Service (ARCS). Arnold was accused by the Communists of working for the CIA. Because the State Department found them relevant in this instance, the flyers’ BW retractions were included in Cowles’ materials. The story of Arnold and the ARCS scandal was covered in my previous article, “CIA, MKULTRA and the Cover-up of U.S. Germ Warfare in the Korean War.”

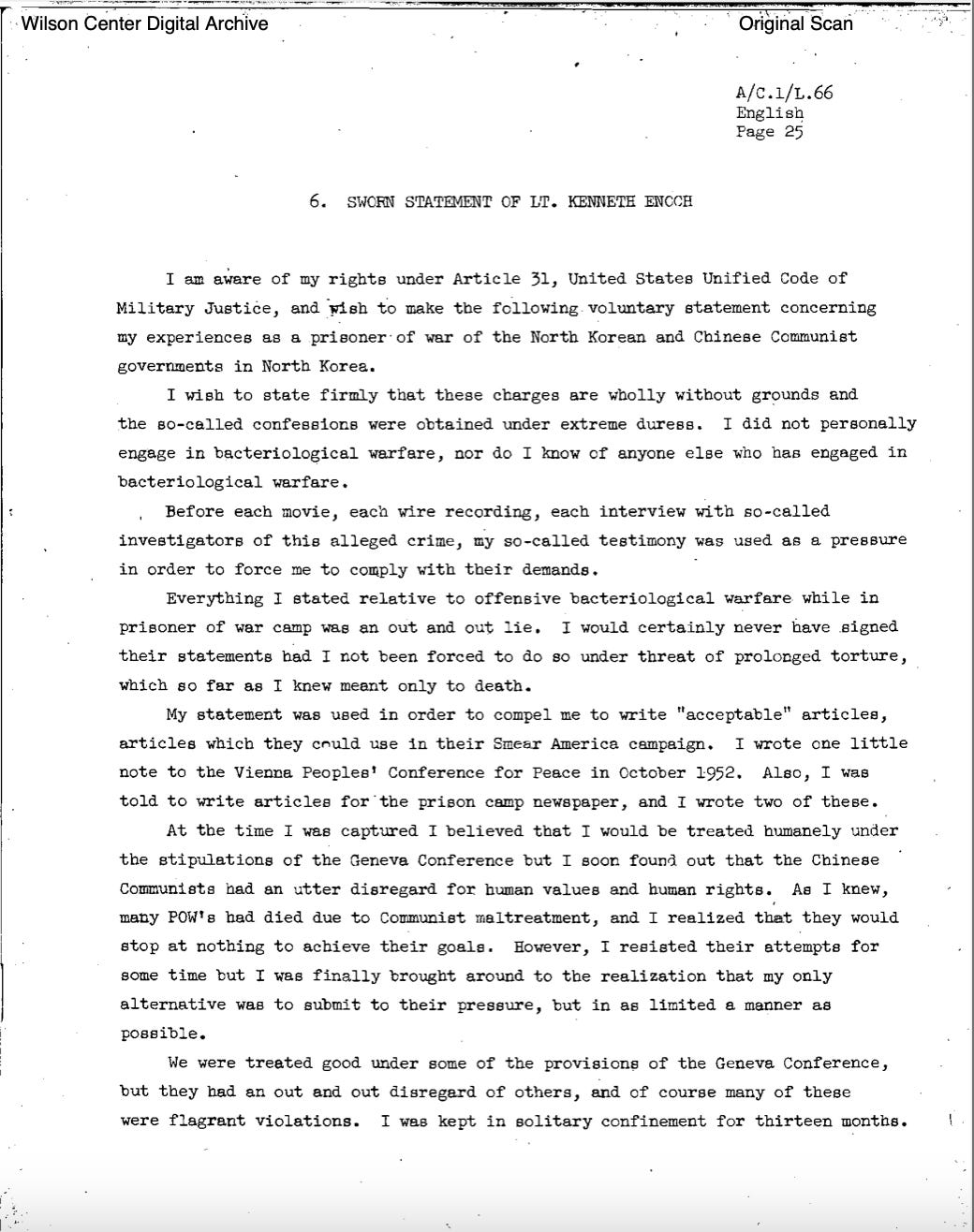

Enoch’s statement, like that of others given and reproduced by both the UN and the Wilson Center Digital Archive, is prefaced by his formal recognition that he understands that he has rights under Article 31 of the Unified Code of Military Justice. Article 31 concerns issues surrounding self-incrimination, and states, among other things, “No person subject to this chapter may compel any person to incriminate himself or to answer any question the answer to which may tend to incriminate him.” For a full text of the Article 31, see the link directly above. In any case, there’s no way that the airmen retracting their statements did not understand they were potentially in some kind of legal peril.

SWORN STATEMENT OF LT. KENNETH ENOCH

I am aware of my rights under Article 31, United States Unified Code of Military Justice, and wish to make the following, voluntary statement concerning my experiences as a prisoner of war of the North Korean and Chinese Communist governments in North Korea.

I wish to state firmly that these charges are wholly without grounds and

the so-called confessions were obtained under extreme duress. I did not personally engage in bacteriological warfare, nor do I know of anyone else who has engaged in bacteriological warfare.Before each movie, each wire recording, each interview with so-called investigators of this alleged crime, my so-called testimony was used as a pressure in order to force me to comply with their demands.

Everything I stated relative to offensive bacteriological warfare, while in prisoner of war camp was an out and out lie. I would certainly never have signed their statements had I not been forced to do so under threat of prolonged torture, which so far as I knew meant only to death.

My statement was used in order to compel me to write "acceptable" articles, articles which they could use in their Smear America campaign. I wrote one little note to the Vienna Peoples' Conference for Peace in October 1952. Also, I was told to write articles for the prison camp newspaper, and I wrote two of these.

At the time I was captured I believed that I would be treated humanely under the stipulations of the Geneva Conference but I soon found out that the Chinese Communists had an utter disregard for human values and human rights. As I knew, many POW's had died due to Communist maltreatment, and I realized that they would stop at nothing to achieve their goals. However, I resisted their attempts for some time but I was finally brought around to the realization that my only alternative was to submit to their pressure, but in as limited a manner as possible.

We were treated good under some of the provisions of the Geneva Conference, but they had an out and out disregard of others, and of course many of these

were flagrant violations. I was kept in solitary confinement for thirteen months.I was kept in two camps where they had no POW sign to protect us from air attacks. The diet during the winter was of very low nutritional value and caused much sickness. I had almost constant diarrhea during my period of captivity. I had it about twenty times, for five or six days at a time. This made me very weak and nervous.

I did not participate in any type of bombing raids which could even remotely be classed as germ raids or bacteriological warfare raids.

I have not heard from any other source, other than the Chinese Communists, that the United Nations Command had employed weapons of bacteriological warfare.

(Signed) Kenneth Enoch

KENNETH ENOCH, A02C69988

1st Lt, USAFSworn to and subscribed before me this 23d day of September 1953 at Parks Air Force Base, California

(Signed) Clifford A. Sheldon

CLIFFORD A. SHELDON

Colonel, USAF

Staff Judge Advocate

A 2010 Documentary Revisits Enoch’s Role

The retraction might have been the end of the Enoch story, so far as his personal record goes. But in 2010, the former Air Force navigator gave an interview to Tim Tate, who was making a documentary about the Korean War-era biological warfare charges for People and Power at Al Jazeera. The finished documentary was titled “Dirty Little Secrets” and remains available for viewing online.

The entire 48 minute film is worth watching in its entirety. As Al Jazeera, in part, described it:

The film followed professor Masataka Mori as he journeyed inside the secretive regime of North Korea to take eye-witness testimony from survivors of, and witnesses to, the germ-warfare attacks. Together with Professor Mori, who has investigated these claims over a 20-year period, Al Jazeera’s team travelled to the villages and townships where the US Army/Air Force allegedly dropped bombs containing infected insects, rodents and food….

The claims put forward by North Korea have been consistently denied by every American administration in the last 60 years. For North Korea, however, the claims only serve to fuel an intense suspicion of the US and its activities in the region.

Of particular interest for me was the portion of the documentary that was an interview with Kenneth Enoch, who was then 85 years old and living in a “senior citizen community” somewhere near Houston, Texas. Enoch died only a few years later in November 2013.

The documentary includes some snippets of Enoch’s filmed confession to China’s press (see portion of film beginning at 32:33), as well as clips from his filmed retraction of his BW confession (beginning at 36:22). Enoch’s filmed retraction and his later at least partial walk-back are worth close examination.

In his filmed 1953 retraction, Enoch was asked, “Can you describe the methods used by the Communist interrogators to secure the statements you made?”

Enoch replied: “Yes, sir. They used both physical and mental pressure. They pushed me around. Stood me at attention for long periods. They forced me to sit at attention. Uh, finally I could see there was no alternative, insanity or death. They threatened me again that I should never leave alive if I didn’t cooperate…. I was forced to read their propaganda and make favorable comments on it, their Russian publications on communism.”

In the AJ People and Power documentary filmed 57 years later, Enoch presented a different view about his POW treatment. When the interviewer remarked to him, “I imagine these were very brutal guards” you had, Enoch replied, “No. No, no. No, no, no” (37:49).

As an example of his treatment as a POW, Enoch described how at one point he was moved by his captors to another building. His room in the building was described as not large but “all I needed,” but quite “cold.” In a humane gesture, his captors brought him a “pot full of charcoal, lit” so he could stay warm. Asked by the AJ interviewer (probably Tim Tate) whether he was indoctrinated by his Chinese captors, Enoch replied, after some hemming and hawing, “I don’t think so. I don’t think they tried to indoctrinate me. They had all kinds of books there if you wanted them, I guess. And if you bought one you didn’t like, just don’t read it” (39:01).

While Kenneth Enoch at 85 was unwilling to present as dire a portrait of his captivity as described in his retraction statement, he nevertheless continued to maintain that he had not been personally involved in any germ warfare activities. As for his written confession, Enoch stated that he only provided “false names, false dates, false anything else I can think of” (39:39).

On this point, the documentarians noted that the names and dates given in the written confession have mostly been confirmed as accurate. (See one example in endnote #1 below.)

The highlight of the interview is Enoch’s discussion on whether biological warfare was used in Korea. His comments are a little obscure or wary, but seem to clearly indicate the truth of the charges, even as he denied personal participation:

First of all, I think that you have to understand what this biological warfare, or whatever you want to call it, is a pretty big field, and has, what you call it? —specialists and evil doctors and all of that nonsense. But, but all the people who deal in that don’t have to go fight. And so that’s a pretty sweet deal for them, you know. But they send you, send it with you…. I didn’t have anything to do with this thing here, this flight. I was just a passenger. (40:57)

Enoch’s Interview with the International Scientific Commission

Totally ignored in all accounts of Kenneth Enoch was the fact that he spent approximately two-and-a-half years in China during World War II. At the time, Enoch was a very young man in his late teens, leaving China probably around age 20. The account of those years comes from the “Interrogation of Lt. Kenneth Enoch” by members of the International Scientific Commission, organized by the World Peace Council and China’s Academia Sinica. While the ISC panel included one scientist from the Soviet Union, and one Chinese assistant, the bulk of the membership was from Western Europe. Its putative leader was a famous and highly-regarded British scientist, Joseph Needham.

It seems to me that Enoch’s early experience of China is worth describing, as it may have informed his understanding of what he would experience when he was captured. He described his early China experience to the ISC, which had made a dangerous journey to interview him and three other U.S. POWs on the germ war issue. They met on August 4, 1952 in a house near the North Korean border with China. The week earlier, the ISC had travelled to Pyongyang, where they had met with Dr. Ri Ping-Nam, the DPRK’s Minister of Health, examining BW lab evidence and meeting with various witnesses of BW attack.

The ISC interview with Enoch was transcribed by the CIA’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service from an English Morse Code shortwave transmission from Beijing to “Southeast Asia, Europe and North America” on September 24, 1952. The full transcript is embedded below.

The reader should feel free, and hopefully even inspired, to read the entire transcript. I’m going to reproduce below only some selected, but I think interesting, parts of what is an after all an eleven page document. So far as I know, the portions of the interview transcribed by FBIS have never been published before, and certainly have not been included in previous histories on the subject of either Mr. Enoch, or more generally, the subject of the airmen confessions of use of biological warfare against China and the DPRK.

Note: The transcript follows the spelling and orthography from the FBIS document. The subheads, which appear to have been added by FBIS, I’ve highlighted with italics for readability sake, and to separate the CIA-FBIS subheads out from the transcript proper. The triplicate asterisks are in the original transcript. It’s not clear if they are meant as ellipses, or perhaps indicating a pause of some sort. It doesn’t appear that much material, if any, was deleted from the original transmission.

The transcript below begins after the initial section of the broadcast, which covered much of what was already documented in Enoch’s written confession. There are added details not reproduced below that are worth reviewing, but those interested will have to discover that for themselves by downloading the PDF offered below.

That’s all the information I have on lectures or germ bombs or anything. My next mission was on Jan. 13. When I didn’t have any germ bombs, I was shot down and captured.

Olivio [2]: Are you a career officer or reserve in the Air Force?

Enoch: At the present I am a reserve officer.

Olivo: In your study of aviation did you study the regulations in connection with aviation as such, and regulations, international regulations, which covered the conduct of war which forbid certain types of warfare?

Enoch: No, sir, we didn’t study, we only studied their regulations which — we didn’t have much of that either, just on POW’s.

Zhukov Verezhnikov [3]: Would you describe what your reaction was to the conduct of germ warfare and also the reaction of your comrades?

Enoch’s Reaction

Enoch: My reaction was — I didn’t understand what was coming off, I certainly had no idea that we would ever use germ warfare. It came as an awful blow to me that we would be perpetrating such actions in North Korea. I had no conception of the scale of the thing. It seemed an isolated incident or something like that. The second mission, that made me feel very terrible, that we were really carrying it out, that is, not just intermittently, we are continuing this thing. Very terrible reaction, but secrecy forced us, in our group anyway, to keep it very quiet and we had no conception, Capt. Amos and I, of anyone else having done such a thing. We were isolated in this instance. Capt. Amos was very shaken up about the thing, a very conscientious man. He had quite a few missions in and certainly wanted to go home, but this thing hit him very hard….

Olivo: When in either the lectures you received or the briefing was it mentioned that there was going to be an experiment in bacteriological warfare or this was part of a general plan of bacteriological warfare?

Enoch: The only time I believe that it was logical for anyone to have told us whether we were going to experiment or really carry it out, was in Mr. Wilson’s lectures, but he really didn’t say. The inference was that we might really use the thing, not just as an experiment with it.

Malterre [4]: Would you say something of your social origin, or more exactly, what were you doing before you entered the Air Force?

Enoch: I’ll give you a brief resume. After I graduated from high school I took a job in a steel mill in my home town at Youngstown, which happens to be a steel town. It was from this job that I entered the Air Force in 1943 and I served for 45 months, 20 missions, 16 of them in B-24’s in China and five missions on Okinawa against Japan. After I left the service in 1947 I again took a job in a steel mill, as a matter of fact, two steel mills in the first summer in order to earn money to help pay my way through college. The Government paid my way but I needed spending money, and my course was electrical engineering. I finished 2 years of electricial engineering. February 1949, I took a job with the power company in town, in Youngstown, we have only one electric power company. I still went to college at nights, night school. It was in 1950, September 1950 I was recalled to active duty from this job at the power company, September 1950, Sept. 2. I was recalled to Langley Field. I was serving with the 45th, 47th rather, Bomb Wing at Langley when I was transferred down to the 4,400th combat crews, a training group to train for B-26’s. That was specifically for Korea. It was in August 1951 that I left the United States for Iwakuni.

Needham [5]: I wonder if I could ask a question. If Dr. Malterre permits that a question can be asked before he continues. I would rather just like to take up that question. I don’t know whether really I have any right to do that; I’d like to take up the question of where Mr. Enoch was in China during the time he was with the Air Force in China during the war. Where he was and what his impressions were of China at that time and whether he’s had occasion to change any of his ideas about China since he’s been here. It might have helped his general background.

Enoch’s Impression of China

Enoch: I was at Luliang in China, Luliang * * *.

Interpreter: At Luliang in Yunnan?

Enoch: Yes, in Yunan about 60 miles east of Kunming and at this time we didn’t have much contact with the people. We were based at the field. As a matter of fact we spent most of our time at the squadron. The town was 2 or 3 miles from the field, 3 miles I should say, and we went there on two occasions or three occasions to buy souvenirs. They had silk scarves in town with embroidery on them. The town was very poor; poor sanitation and the people didn’t have very much. Very friendly people, there was no hostility at all . People would smile. That’s where I learned the term, ding hao, that’s good, and we got along quite well.

People were out plowing their fields then, it was in the springtime. I was only there for 31 or 32 months. (They) had very primitive methods, a wooden stick behind an oxen and it is very difficult to plant rice anyway. [Parenthesis in original - JK] I realize, grant that, but the farms were well tended and seemed rather prosperous. The people worked on the runway at Luliang. They had no tools but it was an extremely huge engineering feat which they accomplished there. To give you a conception, they laid I believe it was an 11,500-foot runway by hand. They had done the excavating and filling for this thing.

As to the economic conditions behind China, at the time I had no conception, and after my capture I thought I was going to be punished or shot or something, tortured right away. After they took my gun away from me, why they they shook my hand and gave me cigarettes. All smiles, were very happy to see me, assured me that nothing was going to happen to me. I realized that these were the same people I had been in contact with at Luliang. The same people, very sincere, very friendly. That was reassuring to say the least. And nothing has happened to change my attitude since. I’ve certainly been well treated by the Chinese people, the Chinese People’s Volunteers, and all my contacts have been almost brotherly, you might say, very, very inspiring, you might say very helpful.

But what has impressed me the most is not the action of the people towards me. That’s a relatively minor thing anyway, in the long run. The things you learn about this country itself, I’ve read Israel Epstein’s “Unfinished Revolution in China,” Alun Falconer’s “New China, Friend or Foe,” and illimitable numbers of pamphlets and magazines, very inspiring, the change in China has been radical, for the better, much better…. [Links added for reference purposes - JK]

Malterre: Would it be correct to say that as a military man you are extremely well disciplined and it wouldn’t occur to you to discuss military laws, military affairs? To discuss or to dispute a military order?

Enoch: Oh, that’s the law. If you dispute an order * * * if you dispute some small order like they want you to sweep the floor or something and you’re an officer and you don’t want to sweep the floor — that’s minor. But to carry out germ warfare or something like that, why you can just bet that drastic measures will be taken against you. There are examples of — not refusal to carry out germ warfare — but people refusing to serve in Korea — such things as that. Why they haven’t shot them but they certainly make life very difficult for them.

Malterre: Did it occur to you that apart from national laws there are also international laws and that if by the execution of a national law you come into conflict with an international law, then you have the right to refuse to execute the national law?

Enoch: Sure, you have the right, but it’s the accepted thing as far as I know, to go ahead and do what — they say, do what the Romans do — for your country, and most everyone else is getting away with it, you can imagine the position of a poor fellow who comes in to Korea with 55 missions ahead of him, all of them possibly germ missions. Of course, it’s a kind of black future to look forward to, but the way I figured it, it probably wouldn’t be all that of my missions would be germ missions. Of course * * * actually, national laws shouldn’t interfere, shouldn’t dispute with international law. Countries should observe international laws. It’s hard to believe that they’d get away with such a thing anyway. It’s all very mysterious — and I think it would take an awful lot of deliberation to even arrive at a — I know the just answer, but just why people do these things — power politics, I think….

Olivio: In you missions did you only know of the “dud” type of bomb, the type of germ bomb described as a “dud” or did you know of other types of germ bombs being employed?

Enoch: No, sir, just this thing that looked like a regular 500-pound bomb.

Needham: Well, that’s really what I was going to ask too. Whether he knew of any other containers?

Zhukov Varezhnikov: During the lectures which you attended did they mention at all the experiments carried out by the Japanese in bacteriological warfare during the Second World War?

Enoch: No, sir, they didn’t mention anything about that.

Needham: In that case, I think the moment has come to ask if everybody is in agreement, to ask Mr. Enoch if he has any concluding remark.

Enoch: Yes, sir, I have just a few remarks to make. I come before you here as a man that’s taken part in this germ warfare, as a man who has actually participated in carrying out this damnable and crused [sic] crime against humanity. I have served these madmen who are throwing down this terrible challenge to the peace-loving people of the world. There are a few high officials in the U.S. Government who have launched this mass murder and they ordered me against, against my conscience, against my will to carry out this crime — to do their dirty work for them — to drop germs and insects on the innocent civilians, the men, women, and children, little children of North Korea. They have every right to peace and happiness, and instead I’ve done my part in bringing them misery and sadness, death.

I cry out against these madmen who have launched this horrible slaughter. I denounce my part in this crime, I was forced to do it by my righteous conscience. I’m a normal person. I have true feelings. I testified against these men now who’ve launched this germ warfare and I stand firmly on my testimony to wage a just fight against this inhuman warfare, and fight for peace and for humanity….

I’d like to call upon the delegates here. Especially to inform — to make their voice heard among the American people. It’s there that the matter is very acute. You can reveal all your damning evidence and testimony that you’ve seen and heard here in North Korea during your inspection, and in Northeast China, and so when the American people come to realize the terrible truth, the horrible significance of this challenge to humanity, they will rise as one to throw down the people who’ve launched this thing. They’ll join the fight surely against these men and against this treachery and deceit and this mass murder, monstrous scheme. They are my people, I know very well this is true….

We must, we must, make ourselves heard, that’s the primary thing. We can and we shall make ourselves heard. Truth will triumph, and when we are heard, we will be understood. When the people fully understand, there will be peace and a bright future for everybody for all mankind. It’s only a question of time and it’s up to us to make the time as short as possible.

Needham: The members of this commission would like to thank Mr. Enoch very much for his clear and calm and honest and sincere testimony which he’s given this afternoon for the commission…. I would like to say to him, as we have said to previous witnesses, that there is no fear whatever that the commission will fail to take all necessary steps to present this report to the world and to get the report known throughout the world….

I thank Ms. Alice Atlas for providing me with the the FBIS files on Lt. Enoch and three of the other airmen who made confessions. The confessions of the latter — Lt. Floyd O’Neal, Lt. Paul Kniss, and Lt. John Quinn (Enoch’s pilot) — are included in the ISC report. Perhaps in the future I can present more from the FBIS transcripts of the ISC interviews with these flyers. A small portion of the ISC interview with Lt. O’Neal was included in an article I wrote in April 2024, while some of the ISC interview with Lt. Kniss was discussed in a Medium.com article I published in March 2023.

Concluding Thoughts

The primary purpose of this post was to provide the raw research materials surrounding one of the most famous and intriguing Air Force officers who, as a prisoner of war during the Korean conflict, made detailed statements regarding his participation in the U.S. BW campaign during that war.

How one interprets such materials depends on the context with which one approaches it. Many years ago, even at the time of the Al Jazeera documentary interview with Mr. Enoch, the controversy over the Korean War allegations about U.S. use of what amounted to weapons of mass destruction in the form of biological weapons remained supposedly unresolved. Today, with the release of a number of CIA communications intelligence reports that cite Chinese and North Korean military communications discussing the BW attacks and how to combat them, our perspective about the material presented herein has definitely changed.

In addition, our knowledge today that the prisoners had been given carte blanche to discuss the BW issue, and presumably other military matters, with their captors, as is revealed here, also colors how one understands the discussions around secrecy, “brainwashing,” confessions, etc. No confessor has ever alluded to the military orders that allowed them to speak relatively freely under interrogation, or at least, such is the case in the materials we have currently available.

It seems likely that the liberal interrogation instructions were not revealed by the BW confessors to their interrogators. Even those who testified at length about the germ warfare program still, at times, seemed to minimize certain aspects. For instance, it seems likely that Enoch knew more about the “4400 CCTG,” or 4400th Combat Crew Training Group, than he let on to his interrogators.

I sympathize with the plight of any prisoner held in the hands of an “enemy” force. It is inherently a stressful, if not scary, situation. I have no doubt that Lt. Kenneth Enoch did the best he could to satisfy the dictates of his conscience in the context of his fear of how authorities might respond to his allegations. I hope that the reader has some sense of the situation Enoch found himself in, and can assess the documents quoted here in that context.

Unlike the higher-ranking officers who confessed to use of germ warfare, Kenneth Enoch was not cognizant of the organization and rationale behind the U.S. decision to use biological warfare. In his confession, and his discussion with the ISC members, he appears to have been as truthful as possible regarding what he saw and experienced.

While Enoch did use the term “imperialism” in his title to his confession, that well may have been suggested by his Chinese captors, or inspired by readings Enoch had accessed during his imprisonment. The bulk of his statement is otherwise free of “Communist” ideological associations, unless one sees his references to “peace” and “humanity” to be influenced by his Chinese captors. I tend to believe Enoch’s reference to the U.S. military officials who organized germ warfare as “madmen” to be his own personal descriptor.

Enoch’s sworn statement of retraction of his confession’s claims is fairly short. Despite accusations of “extreme duress” and threats of torture, Enoch admitted that some of his treatment had been good. In conjunction with his statements to Tim Tate and the AJ documentarians, and to the ISC representatives, his retraction appears to be a fiction imposed upon him by his military and/or intelligence handlers. During the filmed portions I saw in the AJ film, he seems to be reading from a written script.

Neither Kenneth Enoch, nor any of the Air Force officers who confessed to U.S. use of bacteriological weapons in the Korean War, were ever prosecuted for their collaboration. The only BW confessor who faced any quasi-judicial consequences was Colonel Frank Schwable, and that was before an ad hoc Marine Corps “Board of Inquiry,” and not a formal court-marital. He was cleared by the Board of any punishable collaboration. (See discussion of Schwable’s trial here and here.)

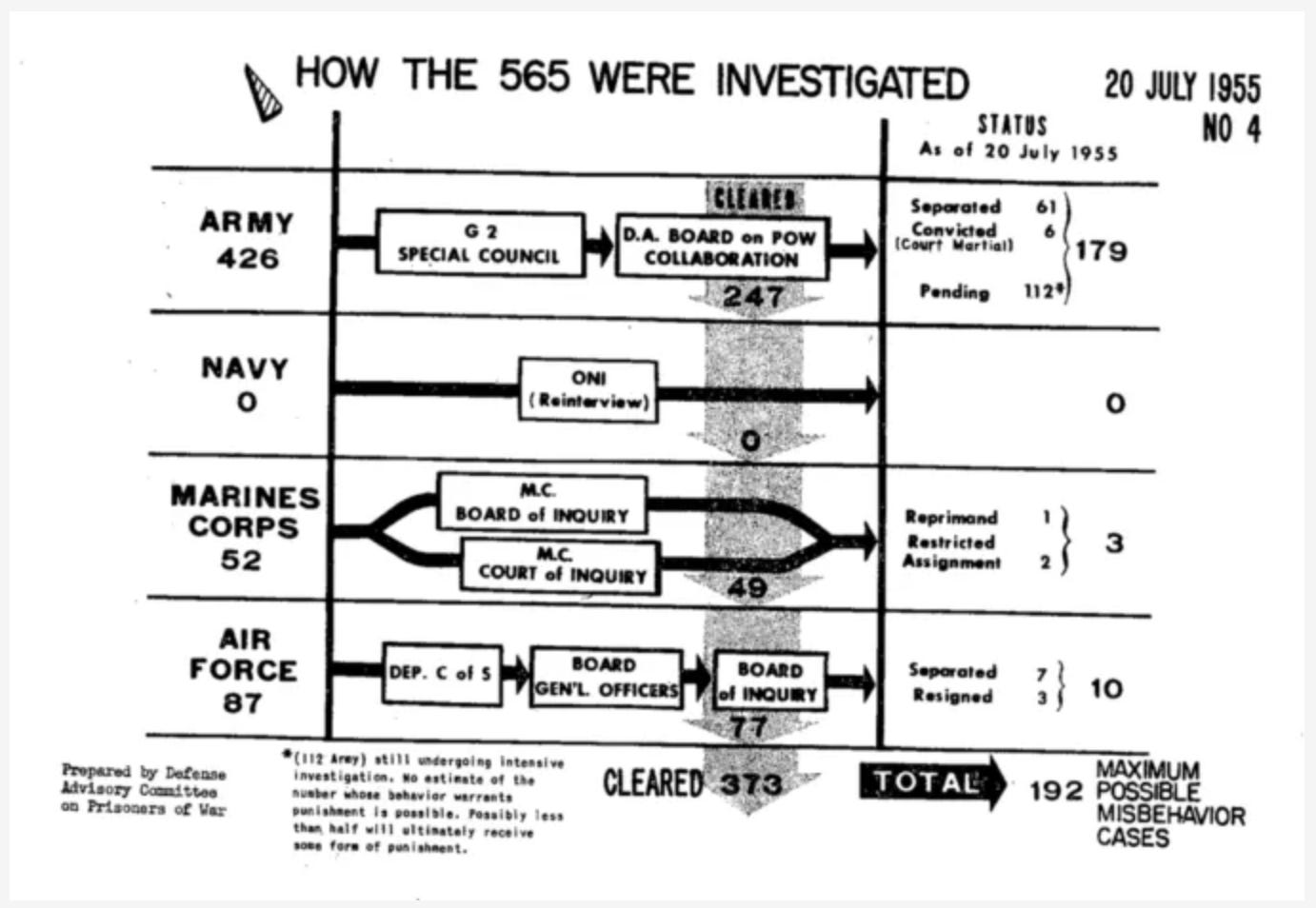

As a matter of comparison with others accused of collaboration with the enemy during the Korean War, I leave the reader with this statement from a 1957 article on POW collaboration, written for Catholic University Law Review:

Of the 4,428 American fighting men returned from enemy prison camps, all of whom were screened, the conduct of 565 was questioned. Three hundred seventy-three cases were cleared or dropped. The services proceeded cautiously with the remaining 192 cases and sifted those to be brought to trial. Since the end of the Korean War, twelve men have been court-martialed on collaboration charges. Two officers and one enlisted man have been acquitted. Six enlisted men have been convicted and sentenced to terms ranging from two years to life imprisonment. Two Lieutenant Colonels and a Major have been convicted: one was dismissed from the Army; one was suspended from rank for two years; and another was sentenced to ten 4 years….

112 cases were still pending as of July, 1955, and it was felt to be fairly certain that substantially less than half of those would be brought to trial.

Endnotes

[1] “4400 CCTG” refers to 4400th Combat Crew Training Group, stationed at Langley Air Force Base between March 12, 1951 and July 19, 1954. According to this website, “The 4400th CCTG was responsible for training crews in all aspects of unconventional warfare and counterinsurgency air operations.” The reference to 4400 CCTG is but one example of how the military information provided by Lt. Enoch can be validated by secondary sources.

[2] “Dr. Oliviero OLIVO (Italy), Professor of Human Anatomy in the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Bologna; formerly Lecturer in General Biology, University of Turin.” — ISC report page 3

[3] “Dr. N. N. ZHUKOV-VEREZHNIKOV (U.S.S.R.), Professor of Bacteriology at, and Vice-President of, the Soviet Academy of Medicine; formerly chief medical expert at the Khabarovsk Trial of Japanese ex-service men accused of participating in bacteriological warfare.” — ISC report page 3

[4] “Mons. Jean MALTERRE (France), Ingenieur-Agricole, Director of the Laboratory of Animal Physiology, National College of Agriculture, Grignon; formerly Livestock Expert, UNRRA; Corresponding Member of the Italian and Spanish Societies of Animal Husbandry.” — ISC report page 3

[5] “Dr. Joseph NEEDHAM (U.K.), F.R.S., Sir William Dunn Reader in Biochemistry, University of Cambridge; formerly Counsellor (Scientific), H.B.M. Embassy, Chungking, and later Director of the Department of Natural Sciences, UNESCO.” — ISC report page 3

[6] Of the individuals named in Needham’s photography, re Jean Malterre, see Endnote [4]. Yen Jen-ying [Yan Renying 嚴仁英] is referenced in Appendix TT of the ISC report as Assistant Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Peking University Medical College. Her MD was obtained at Peking Union Medical College (University of the State of New York), while her post-graduate study took place at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University (1948-1949). She had previously served as Lecturer, Peking University Medical College, 1946-48 (ISC report, pp. 664-665). Yen was one of six “Specialist Liaison Officers” attached to a Chinese Committee of Reception that assisted the ISC in its work (ISC report, pg. 7). She was chosen because of her facility with English, and she must have served as a translator (ISC report, pg. 9).

Dr. Andrea Andreen was an official member of the ISC. At the time, she was also Director of the Central Clinical Laboratory of the Hospitals Board of the City of Stockholm (ISC report pg. 3).

I have sent you a message. Robert